Electoral Count Act of 1887, the Safe Harbor Deadline, and the Election of 1876

[29 Stat. 373, 49th Congress, 2nd Session, 2/3/1887]

After the Presidential election of 1876 exposed serious defects with the process of resolving election disputes, Congress passed the Electoral Count Act of 1887 to avoid a repeat of the Hayes-Tilden election debacle a decade earlier. Among other things, the Act delegates to each state the “final determination” of any election disputes within the state, under specified circumstances.

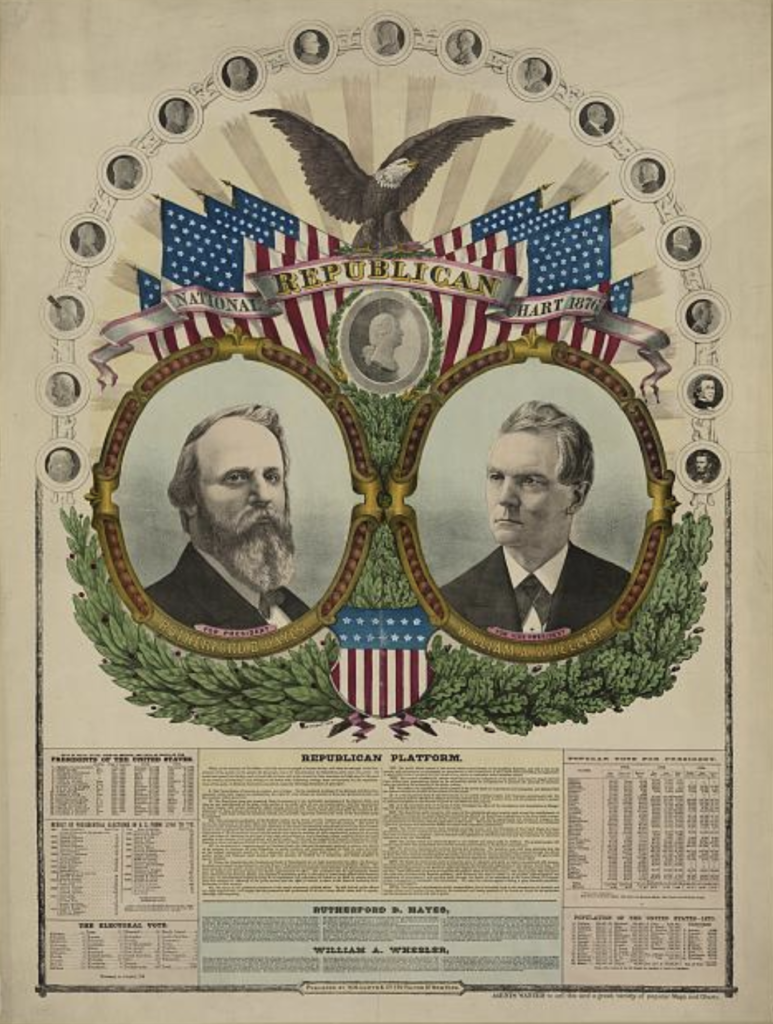

Officially known as “An Act to Fix the Day for the Meeting of the Electors of President and Vice-President, and to Provide for and Regulate the Counting of the Votes for President and Vice-President, and the Decision of Questions Arising Thereon”, the Electoral Count Act (“ECA”) was an effort to avoid the constitutional crisis of 1876, which resulted in the smallest winning margin in Electoral College history – 185 to 184.

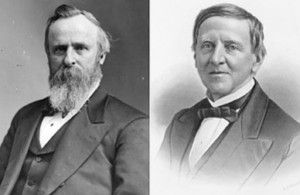

As will be discussed below, Democrat James J. Tilden won the popular vote in 1876 but lost the electoral college vote to Republican Rutherford B. Hayes. Arguably the most controversial presidential election in American history, the disputed election was resolved by the Compromise of 1877 in which the Democrats in Congress conceded the election to Hays in return for the withdrawal of federal troops from the South and the end of Reconstruction.

Provisions of the Electoral Count Act (ECA)

The century old Act, which remains in force today, is codified in 3 U.S. Code § 15. Under the ECA, Presidential elections are subject to the following requirements, deadlines, and objection procedures:

- Counting electoral vote in each state (Section 1): The electors of each state shall meet on the “second Monday in January” at such place in each State as the legislature of such State shall direct.

- State determination is conclusive during “safe harbor” (Section 2): The Act reserves to the states the “final determination of any controversy or contest concerning the appointment of all or any” of its electors, provided that any disputes are resolved at least six days prior to the meeting of the electors, which “shall be conclusive”. Known as a “safe harbor” date, the six day deadline doesn’t force states to make a final determination during the window, but is intended to encourage the states to do so if they want their decision to be binding on Congress. See 3 U.S.C. §5.

- Counting electoral votes by Congress (Section 4): The Senate and House shall meet at 1:00 p.m. on the afternoon of the second Wednesday of February for the opening and reading of the electoral vote.

- Opening and reading certificates: The President of the Senate (the Vice President) opens the electoral certificates in the presence of a joint session of Congress, and hands them to the tellers, two from each house, who read them aloud and record the votes.

- Objection procedures: The Act provides procedures for counting electoral votes, handling objections and questions, and announcing a decision. An objection must be made in writing and must be signed by at least one Senator and one member of the House. An objection “shall state clearly and concisely, and without argument, the ground thereof.” When a proper objection is submitted, the House and Senate are required to separately meet and consider it.

- Binding procedure unless Congress agrees otherwise: Most importantly, the Act pre-commits Congress to follow the procedures specified in the Act. Congress has also agreed in the Act to defer to the states as to the resolution of election disputes, unless both the House and Senate agree to reject the state certification based on a valid objection described above. Using mandatory language, Section 4 of the Act provides that no electoral vote “shall be rejected” from any state which has been “regularly given by electors whose appointment has been lawfully certified according to section three of this act…” See 3 U.S.C. §15.

- Default to state certification: In the event that the House and Senate disagree, the electors certified by the governor of a state are required to be counted.

- Debate time limit (Section 6): When the Senate and House separately meet to consider valid objections, each Senator or Representative may speak for “five minutes, and not more than once; but after such debate shall have lasted two hours it shall be the duty of the presiding officer of each House” to put the question to a vote.

- No recess (Section 7): The joint meeting of Congress is prevented from taking a recess after 5 calendar days if a decision has not been reached.

The ECA was adopted in 1887, 11 years after the disputed election of 1876. While some suggest that the law was adopted as a temporary, stop-gap measure, it remains in force today to resolve disputes when a state submits two different Electoral College vote counts. The 809-word statute contains seven sections, but a single 275-word sentence is particularly noteworthy, leading one commentator in 1887 to describe the law as “unintelligible”.

Election of 1876

After President Grant declined to run for a third term, the Republicans nominated Ohio Governor, Rutherford B. Hayes. The Democrats selected New York Governor and reformer, Samuel J. Tilden, who had famously taken on the “Tweed Ring” of corrupt New York politicians. While both candidates were moderates who shared much in common, their parties engaged in widespread voter fraud in the hotly contested Presidential election of 1876.

Democrat James Tilden seemingly won the popular vote. He was leading with 184 electoral votes (to Hayes’ 163 votes), but remained one vote shy of the required 185 vote threshold. The votes in four states were challenged (Louisiana, Florida, South Carolina, and Oregon), with electors for both Tilden and Hayes claiming victory and submitting competing slates for consideration.

The House was controlled by Democrats and the Senate was controlled by Republicans. Due to allegations of widespread voter fraud, in January of 1877, President Grant and Congress passed the Electoral Commission Act which set up a special, statutory electoral commission to resolve the dispute.

The unprecedented 15 member bipartisan commission was composed of 5 members of the House, 5 Senators, and 5 Supreme Court justices (with four Justices named in the Act to select a fifth justice). The Electoral Commission Act provided that the Commission’s recommendations were binding on the House and Senate. The commission announced its decision two days before the inauguration, certifying a vote of 8-7 along party lines to award all contested electoral votes to Hayes. As a result, Hayes won the disputed election, despite his loss of the popular vote.

Until the “Compromise of 1877” was finally hashed out, the controversy dragged on for months. The night before the expiration of President Grant’s term, the Senate announced that Hayes had been elected. Southern Democrats agreed to support Hayes’ claim for the Presidency in return for increased funding for Southern internal improvements, withdrawal of federal troops, and an end to Reconstruction.

To end the constitutional crisis, on March 1, 1877, Speaker of the House Samuel Randall put country before party. Even though he was a Tilden loyalist, Randall refused to permit continued obstructionist maneuvers by his party. In the House’s so-called “stormiest” session—with pistols ready and ladies cleared of the galleries—Randall was forced to ask the sergeant-at-arms to restrain Democratic colleagues. Vermont was counted for Hayes as demanded by Republicans, and the voting process was finalized in the early hours on March 2.

On March 3, the House of Representatives passed a dissenting resolution declaring that Tilden had been “duly elected President of the United States.” Nevertheless, Hayes was peacefully sworn in on March 5.

The outcome of the electoral commission’s decision is known as the Compromise of 1877, which returned the South to “local rule” with the removal of federal troops. This decision effectively ended the Reconstruction era following the Civil War. In short order, Southern Democrats took over southern legislatures and began implementing invidious Jim Crow laws to disenfranchise African American voters.

Recent controversy involving the ECA

In 2020 the Electoral Count Act of 1887 has become newsworthy, after President Donald Trump requested intervention by state legislatures and governors to send the presidential election into the House. As set forth below, proponents of the “legislative appointment” theory of Presidential elections selectively read from the Constitution and overlook applicable language in the Electoral Count Act.

President Trump’s attorneys have cited to Article 2, Section 1, Clause 2 of the Constitution to suggest that the Constitution empowers state legislatures to unilaterally decide presidential elections through “legislative apportionment”. Article 2, Section 1, Clause 2 provides that:

Each state shall appoint, in such manner as the Legislature thereof may direct, a number of electors, equal to the whole number of Senators and Representatives to which the State may be entitled in the Congress. . .

The President and his attorney largely overlook, however, another provision in Article 2, Section 1 which necessarily factors into the analysis. While Clause 2 provides the each state shall appoint electors “in such manner” as the Legislature may direct, Clause 4 of Article 2, Section 1 provides that Congress determines the “time and choosing” of the electors. When enacting the Electoral Count Act, Congress was exercising this authority.

Article 2, Section 1, Clause 4 provides:

The Congress may determine the Time of choosing the Electors, and the Day on which they shall give their Votes; which Day shall be the same throughout the United States.

For nearly 200 years, every state has chosen its electors by popular vote. While a state legislature could theoretically decide to reclaim its authority to chose the “manner” of appointing electors, this decision would need to be made before Election Day. In other words, the decision not to utilize the popular vote would need to be made prior to, not after an election.

Importantly, the enactment by Congress of the Electoral Count Act, which supersedes state law, prohibits the choice of electors from being made based on laws passed after Election Day. Moreover, the Electoral Count Act gives “conclusive” effect to the votes cast as outlined in the safe harbor provisions in the Act. See 3 U.S.C. §5 & §15.

The Safe Harbor provision in 3 U.S.C. §5 is copied below in its entirety:

If any State shall have provided, by laws enacted prior to the day fixed for the appointment of the electors, for its final determination of any controversy or contest concerning the appointment of all or any of the electors of such State, by judicial or other methods or procedures, and such determination shall have been made at least six days before the time fixed for the meeting of the electors, such determination made pursuant to such law so existing on said day, and made at least six days prior to said time of meeting of the electors, shall be conclusive, and shall govern in the counting of the electoral votes as provided in the Constitution, and as hereinafter regulated, so far as the ascertainment of the electors appointed by such State is concerned.

Several legal commentators have argued that the Act is unconstitutional as it restricts the authority of the House and Senate to control their internal procedures and rules.

The Supreme Court has generally held that the House and Senate have plenary power over their own rules under Article I, Section 5, which provides that “[e]ach House may determine the Rules of its Proceedings . . .”

The Constitution does not say who, if anybody, has the “power” to count electoral votes. The Twelfth Amendment merely says “the votes shall . . . be counted,” as follows:

“The President of the Senate [the sitting Vice President] shall, in the presence of the Senate and House of Representatives, open all the certificates and the votes shall then be counted.”

Nevertheless, in July of 2020 in the case of Chiafalo v. Washington, the United States Supreme Court unanimously ruled that members of the Electoral College could be forced to vote for the winner of the popular vote. According to the Court, states may properly instruct so-called “faithless electors” that they “have no ground for reversing the vote of millions of its citizens.” This direction “accords with the Constitution – as well as with the trust of a nation that here, We the People rule.”

By December 8, 2020 (the “safe harbor” date in 2020), all 50 states certified their election results in the Presidential Election of 2020. In the opinion of Statutesandstories.com, it is unfortunate that extraordinary efforts have been made to disenfranchise millions of swing state votes. While 2020 has witnessed dangerous challenges for American democracy, ultimately the United States is built upon a robust system of checks and balances and the U.S. Constitution will endure. It will be interesting to see whether or not future efforts are made to update the Electoral Count Act of 1887 in light of the Election of 2020.

Additional reading:

Presidential Election of 1876: A Resource Guide (Library of Congress)

Proceedings of the Electoral Commission of 1877

Vasan Kesavan, Is the Electoral Count Act Unconstitutional?

Chris Land & David Schultz, On the Unenforceability of the Electoral Count Act