Executive Privilege under the Washington, Adams and Jefferson administrations (1789-1809)

The term “executive privilege” is not explicitly mentioned in the constitution. Nevertheless, the founding generation unmistakably recognized the competing interests in both Congressional oversight and the need for the President to withhold information when doing so was in the public interest. To the extent that the founders grappled with questions of executive privilege in their day, this post will explore early precedents that they established over 200 years ago.

The preceding post, Executive Privilege (Part I), explored the doctrine and theory of executive privilege. A subsequent pending post, Executive Privilege (Part III) will examine examples of how executive privilege was applied by the courts in the cases of U.S. v. Burr in 1807 and U.S. v. Nixon in 1974.

This post, Executive Privilege (Part II), examines the origins of executive privilege during the founding generation. President Washington was faced with issues of executive privilege on three separate occasions: i) the St. Clair investigation in 1792, ii) the Morris dispatches in 1794, and iii) the Jay’s Treaty instructions in 1796. Interestingly, the precedents that Washington established, in consultation with his cabinet, differed in each instance.

Washington’s invocation of executive privilege is best understood by reviewing the particular circumstances of each example. Among the variables to be considered when interpreting each precedent were: 1) the text of the specific Congressional request, 2) the context of each request, 3) the kind of information sought to be protected by the President, and 4) the Congressional reaction to the assertion of executive privilege.

After reviewing the three instances when questions of executive privilege were raised during the Washington administration, this post will also examine the use of executive privilege by Presidents Adams, Jefferson, Madison, Monroe and Jackson. In particular, President Jackson’s withholding of information from Congress during a dispute over the Second Bank of the United States remains one of the most heated showdowns between a President and Congress. The result was the first – and only – time that a President was censured by the Senate.

Recognition of the importance of early precedent:

When George Washington took the oath of office in New York in April of 1789, he knew that the experiment in democracy that he was leading was without precedent. Washington also understood that future generations would look to the early precedents that were being set by his administration. His awareness that “history was watching” is illustrated by Washington’s correspondence with Adams, Madison, Hamilton, Jay and Randolph in the opening months of his administration.

After his election, Washington emphasized that he wanted “candid and undisguised opinions” from his advisors. In a letter to Madison dated May 5, 1789, Washington explained that he wanted the precedents that he established to be based on “fixed and true principles”:

As the first of everything, in our situation will serve to establish a Precedent, it is devoutly wished on my part, that these precedents may be fixed on true principles.

Likewise, in a May 10, 1789 letter to Adams, Washington wrote that:

Many things which appear of little importance in themselves and at the beginning, may have great and durable consequences from their having been established at the commencement of a new general government.

Similar letters were sent to other trusted advisers, who would eventually be appointed to Washington’s cabinet. This same appreciation for the future consequences of their decisions was evident in 1792, when the issue of executive privilege was raised for the first time in the context of the nation’s first Congressional investigation.

Washington’s use of executive privilege: President George Washington was confronted with the issue of executive privilege on three separate occasions. Washington’s response – and his Cabinet’s recommendation – differed in all three situations, illustrating that executive privilege is a fact specific inquiry.

Investigation into St. Clair’s Defeat (1792)

In November of 1791 the U.S. military suffered a devastating defeat at the Battle of a Thousand Slain (also known as the Battle of the Wabash River or St. Clair’s defeat). During the Northwest Indian War, the Miami and Shawnee Indians were led by Chief Little Turtle. Their victory over General St. Clair was arguably the most decisive defeat in American military history, occurring eighty-five years prior to Custer’s defeat at Little Big Horn. Of the 1,000 troops led by St. Clair, only 24 escaped unharmed (632 were killed and 264 wounded), representing a casualty rate of 97.4%. Because the American army was so small, these losses wiped out approximately 1/4 of the entire U.S. Army at the time.

Congress responded in March of 1792. Faced with these shocking losses, Congress adopted an Act for the Protection of the Frontiers, which created three additional military regiments. In May of 1792, Congress adopted The Militia Acts of 1792, which delegated power to the President to call up state militias and provided for the regulation of state militia and the conscription of troops.

To investigate General St. Claire’s defeat, Congress appointed a seven member Special Committee on March 27, 1792, the first inquest of its kind. The decision to appoint the Special Committee was controversial. Representative William Smith of South Carolina argued against the inquest, which he thought could be viewed as implied impeachment of Washington.

Nevertheless, the House voted to grant the Special Committee the power “to call for such persons, papers, and records, as may be necessary to assist their inquiries.” 3 Annals of Congress 536 (1792):

Resolved, That a committee be appointed to inquire into the causes of the failure of the late expedition under Major General St. Clair; and that the said committee be empowered to call for such persons, papers, and records, as may be necessary to assist their inquiries.

The motion was made by Madison and passed 44-10 on March 27, 1792. The Committee proceeded to request that Secretary of War Henry Knox supply all communication and records relevant to the failed military campaign against the native Americans in the Northwest territory.

Seeking instructions, Knox delivered the Congressional request to Washington, who promptly convened his Cabinet on March 31, 1792. The four member Cabinet consisted of Secretary of State Jefferson, Secretary of Treasury Hamilton, Secretary of War Knox, and Attorney General Randolph. As described by Jefferson’s diary, Washington “wished that so far as it should become precedent, it should be rightly conducted.” Washington did not doubt the propriety of the House’s inquiry, but he “could readily conceive there might be papers of so secret a nature as that they ought not to be given up.” Because the Cabinet members were not prepared, they “wished time to think and enquire.”

The Cabinet reconvened on April 2. According to Jefferson’s Memoranda of Consultations with the President, all members of the Cabinet were of one mind and agreed on the following four points:

1. that the house was an inquest and therefore might institute enquiries. 2. that they might call for papers generally. 3. that the Executive ought to communicate such papers as the public good would permit, and ought to refuse those the disclosure of which would injure the public. Consequently were to exercise a discretion. 4. that neither the Committee nor House had a right to call on the head of a department, who and whose papers were under the Presidt. alone, but that the Committee shd. instruct their chairman to move the house to address the President.

Two days after the Cabinet meeting, the House revised its motion as follows, likely reflecting that at least one member of the Cabinet communicated the administration’s conclusions to Madison:

Resolved, that the President “be requested to cause the proper officers to lay before this House such papers of a public nature, in the Executive Department, as may be necessary to the investigation of the causes of the late expedition under Major General St. Clair.” 3 Annals of Congress 536 (1792) (emphasis added)

After reviewing the requested papers, the Cabinet advised Washington “that there was not a paper which might not be properly produced.” Thereafter, Washington fully cooperated with the Congressional investigation. At Washington’s request, Knox and Hamilton provided the House with the requested papers and the two Cabinet members personally testified before the committee.

The St. Clair precedent – which was the first Congressional request to the White House for records – establishes that a president had discretion to withhold information from Congress when he believed doing so was in the public interest. On the other hand, Washington did not withhold information that he knew could be politically damaging. After deliberating with his Cabinet, Washington agreed to release all requested military records.

While the St. Clair defeat and investigation was no doubt a big embarrassment for the his administration, Washington was forthcoming nonetheless. In other words, Washington chose to cooperate, rather than conceal information in an effort to protect his reputation. Washington understood that the public interest came before politics (and/or the mere reputational interests of the President). Thus, the St. Clair precedent is contrary to the White House counsel’s argument two hundred years later that the president’s ability to “influence” public opinion would undermine his ability to conduct foreign policy.

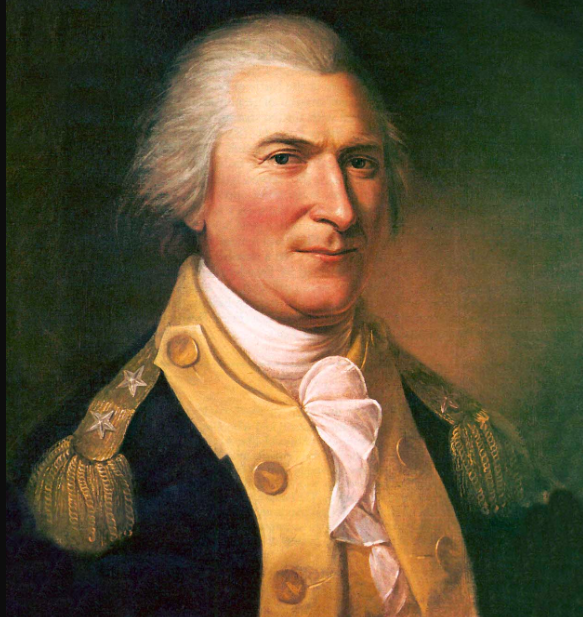

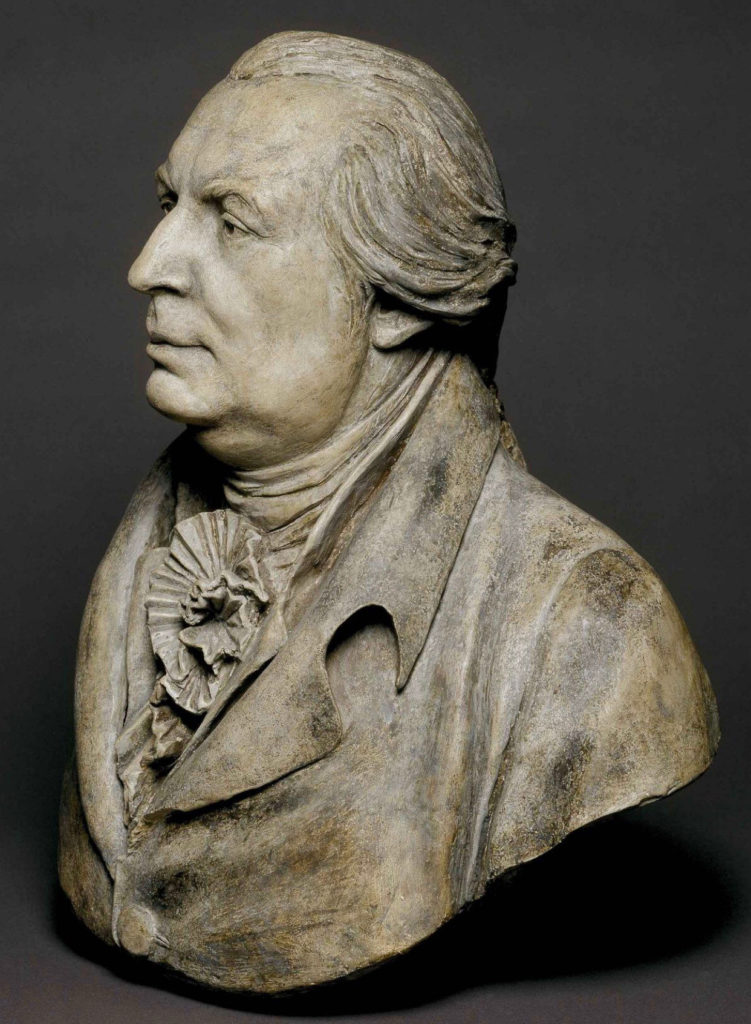

Diplomatic correspondence of Ambassador Gouverneur Morris (1794):

The second incident involving the issue of executive privilege – and the first time that President Washington withheld information from Congress – occurred in 1794. The newly elected Third Congress convened in December of 1793. Less than two years after the St. Clair investigation discussed above, the Senate requested diplomatic communications involving the American Ambassador to France, Gouverneur Morris. This would become the first instance where a President exercised executive privilege in the face of a Congressional request for documents.

At the time, the French Revolution had devolved into the bloody Reign of Terror. As early as the summer of 1792, Washington began receiving reports from Paris that the the Revolution was becoming increasingly violent. King Louis XVI was executed on January 23, 1793. France declared war on Britain shortly thereafter. In April of 1793, Washington issued his Proclamation of Neutrality, declaring that the United States would remain neutral in the European conflict. While welcomed by Federalists, the Proclamation was seen as disloyal to France which had assisted the colonies during the American Revolution.

With Federalists supporting Britain and Jefferson’s emerging Democratic-Republican party supporting France, Morris became an easy political target in the partisan cross fire. Morris’ views strongly aligned with Hamilton’s opinion of the role of a strong federal government and the importance of remaining neutral.

Even though Morris was a high ranking Federalist, his confirmation by the Senate in 1791 provoked a bitter battle. Morris was born into one of New York’s most prominent families. His pro-British leanings were well known, as was his decidedly aristocratic bent, leading Jefferson to describe Morris as a “high flying monarchy man.” He was ultimately confirmed on January 12, 1792 by a 16-11 vote, illustrating the deepening party lines in the Third Congress.

On January 17, 1794, the Senate approved a motion directing Secretary of State Edmund Randolph “to lay before the Senate the correspondence which have been had between the Minister of the United States at the Republic of France and said Republic, and between said Minister and the Office of Secretary of State.” Realizing the procedure followed by the House two yeas earlier, the Senate amended its motion to address the President rather than Morris. It is unclear who introduced the original motion, but it was no doubt intended to embarrass Morris and the Washington administration.

Using the protocol that he established in 1792, Washington asked his cabinet to review the Congressional request and make recommendations. In a letter dated January 26, 1794 to Washington, former Attorney General and newly appointed Secretary of State Edmund Randolph expressed his concerns that Morris’ correspondence contained “harsh expressions on the conduct of the rulers of France, which, if returned to that country, might expose him to danger.”

The Cabinet unanimously agreed on January 28th that Washington had discretion to withhold information from Congress. In particular, Alexander Hamilton and Henry Knox recommended that Washington withhold all of the requested correspondence, while Secretary of State (and former Attorney General) Randolph advised that Washington should only withhold information that Washington deemed “improper.” Newly appointed Attorney General William Bradford wrote to Washington that it was the president’s “duty” to withhold “correspondence as in the judgment of the Executive shall be deemed unsafe and improper to be disclosed.”

In a letter dated February 26, 1794 to the Senate, Washington responded to the Senate that he was providing the requested information “except for those particulars, which in my judgment, for public considerations, out not to be communicated”:

After an examination of [the correspondence], I directed copies and translations to be made, except in those particulars, in my judgment, for public considerations, ought not to be communicated.

These copies and translations are now transmitted to the Senate; but he nature of them manifest the propriety of their being received as confidential.

Thus, in the first application of the concept of executive privilege, Washington produced to the Senate copies of thirty-nine out of forty of Morris’ letters, along with enclosures and translated attachments containing Morris’ correspondence with French officials. Washington withheld only one of Morris’ letters (relating to the United States debt owed to France) and redacted 48 separate sensitive matters, including controversial opinions expressed by Morris.

Consistent with his pro-British views, Morris had used colorful and derogatory language in his assessment of France and its Revolutionary leaders. Some redactions were as short as a single name, while others were as long as one to two full paragraphs. A sample of the forty-eight redactions, illustrating that Morris was not afraid to express strong opinions, are copied below:

“The best picture I can give of the French nation is that of cattle before a thunderstorm.” 6/10/1792 letter to Jefferson

Morris described the “open contempt of religion” in France. He expressed his view that the French live a life of loose morals and “easy principles” at home and attempt to transmit these “want of morals” abroad. Morris explained that his opinion of France was shared in Flanders and Germany. 12/21/1792 letter to Jefferson

“I have no confidence in the morals of the people.” 8/1/1792 letter to Jefferson Morris referred to the “ignorant populace” in France.

Morris’ correspondence disclosed that he utilized a network of unnamed informants and the “confidence reposed in me might in the Course of Events prove fatal to my Informant.” 7/10/1792 letter to Jefferson

Other redactions involved the Marquis de Lafayette, who was a close friend of Washington and Hamilton. It is thus not surprising that Washington redacted plans by Lafayette to lead an attack against the Jacobins.

Morris accurately predicted the emergence of “despotism here” and “that national bankruptcy” of the French government seemed “inevitable.” 6/10/1792 letter to Jefferson

Morris also opined that the acts of the National Assembly freed the United States from its treaty obligations to France. “Perhaps you will see that all the Advantages desir’d do already exist that the Acts of the constituent Assembly have in some Measure set us free from our Engagements and that encreasing daily in Power we may make quite as good a Bargain some Time hence as now.” 2/13/1793 letter to Jefferson

Importantly, Washington was transparent in his use of executive privilege. Each of the Morris redactions was plainly identified in the copies reproduced for the Senate. Nevertheless, the Senate declined to challenge Washington’s redactions, or his assertion of a right to withhold “particulars,” which in his judgement “ought not to be communicated.”

Jay’s Treaty Instructions (1796):

Jay’s Treaty was negotiated by Chief Justice John Jay in 1794. Formally known as the Treaty of Amity, Commerce, and Navigation between His British Majesty and the United States, the highly controversial treaty was orchestrated by Alexander Hamilton. While unpopular, Jay’s Treaty succeeded in delaying war between America and England for nearly two decades, until the War of 1812.

Despite Washington and Hamilton’s best efforts to avoid entanglements in European affairs, Jay’s Treaty provoked one of the most divisive political battles in American history. For a detailed discussion of Jay’s Treaty refer to Jay’s Treaty Part 1 (background and treaty provisions); Part 2 (the bitter ratification battle); Part 3 (Hamilton’s Camillus essays defending Jay’s Treaty).

After Jay’s Treaty was narrowly ratified by the Senate, Jefferson, Madison and their allies attempted to defund the treaty in the House. In 1796, on a motion by Robert Livingston, the House requested the pre-negotiation instructions to John Jay.

Resolved, That the President of the United States be requested to lay before this House a copy of the instructions given to the Minister of the United States who negotiated the Treaty with Great Britain, communicated by his Message of the first instant, together with the correspondence and other documents relative to the said Treaty.

While he was no longer in Washington’s cabinet, Hamilton advised Washington that the House was not entitled to the diplomatic correspondence that Hamilton had drafted to Jay. Hamilton opined that it would be “fatal to the negotiating power of the government if it is to be a matter of course for a call from either House of Congress to bring forth all the communications, however confidential.”

By letter dated March 7, 1796 to Washington, Hamilton wrote that:

It seems to me that something like the following answer by the President will be advisable.

“A right in the House of Representatives, to demand and have as a matter of course, and without specification of any object all communications respecting a negotiation with a foreign power cannot be admitted without danger of much inconvenience. A discretion in the Executive Department how far and where to comply in such cases is essential to the due conduct of foreign negotiations and is essential to preserve the limits between the Legislative and Executive Departments. The present call is altogether indefinite and without any declared purpose. The Executive has no cases on which to judge of the propriety of a compliance with it and cannot therefore without forming a very dangerous precedent comply.

It does not occur that the view of the papers asked for can be relative to any purpose of the competency of the House of Representatives but that of an impeachment.”

Agreeing with Hamilton, and borrowing from Hamilton’s March 7th suggestions, Washington responded to the House by letter dated March 30. In his response to the Livingston motion, Washington respectfully stated the reasons why the House was not entitled to the requested records:

The nature of foreign negotiations requires caution, and their success must often depend on secrecy; and even when brought to a conclusion a full disclosure of all the measures, demands, or eventual concessions which may have been proposed….

As, therefore, it is perfectly clear to my understanding, that the assent of the House of Representatives is not necessary to the validity of a treaty…and on these, the papers called for can throw no light; and as it is essential to the due administration of the government, that the boundaries, fixed by the constitution between the different departments, should be preserved: a just regard to the constitution, and to the duty of my office, under all the circumstances of this case, forbid a compliance with your request.

In other words, as a threshold matter, Washington explained that secrecy was critical for the success of diplomacy. Moreover, because Jay’s Treaty had already been approved by the Senate, consent by the House of Representatives was unnecessary. Of course, this opinion was only half true as the House controls the power of the purse. Nevertheless, Washington and Hamilton understood that the funding vote in the House would be extremely close and they did not want to give the treaty’s opponents any additional ammunition to use to undermine the treaty. Their assessment was proven correct, as the House narrowly voted 50-49 to fund Jay’s Treaty.

After debating Washington’s response, the House passed two non-binding resolutions. First, the House asserted that Congress need not stipulate its reasons for requesting information. Second, the House proclaimed that it has a legitimate role in considering the expediency with which a treaty is to be implemented. 5 Annals of Congress (1796) 771; 782-783.

During the house debate, James Madison expressed his view that, “the Executive had a right, under a due responsibility, also, to withhold information, when of a nature that did not permit disclosure of it at the time…If the Executive conceived that, in relation to his own department, papers could not be safely communicated, he might, on that ground, refused them, because he was the…judge within his own department.” 5 Annals of Congress (1796) 773

The XYZ Affair and other early precedents:

President John Adams declined to invoke executive privilege in 1798, when releasing sensitive information proved politically useful. At the time, America and France were engaged in naval warfare in the Caribbean (known as the Quasi-War) which Adams hoped to resolve through good faith negotiations. During the so-called XYZ Affair, the pro-French Democratic Republicans wrongly assumed that Adams was withholding information which would show France in a positive light. It turned out, however, that the French ministers were seeking bribes as a precondition to peace negotiations. Here the lesson to Congress would be to be careful what you ask for.

After Adams reported that the French would not accept peace on reasonable terms, the Democratic Republicans attacked Adams and his “insane message.” On March 19, 1798, Adams requested that Congress arm American vessels, improve coastal defenses, and increase military funding.

In the toxic political climate, Jeffersonian newspapers were highly critical of Adams, with at least one paper calling for Adams’ resignation. For example, an open letter to Congress published in the Aurora condemned Adams and the “mysterious secrecy” of the French mission. Newspaper publisher Benjamin Franklin Bache (Benjamin Franklin’s grandson) opined that President Adams’ request for military preparations be postponed until Congress could be convinced that Adams had pursued every alternative to war.

On April 2, 1798, Senator Albert Gallatin, the leader of the Democratic Republicans, sought disclosure of the dispatches from the American envoys. The Federalists, having learned the substance of the communications, recognized their opportunity to embarrass Jefferson and his party. In a dramatic scene on the Senate floor, the Federalists joined with their rivals to demand the immediate release of the diplomatic correspondence with the American mission to Paris.

In the face of mounting political pressure, Adams released the dispatches the following day. On April 3, he cleared the Senate chamber and locked the doors. With spectators and the press left to speculate, Adams dropped a bombshell in Congress. The XYZ dispatches revealed that the French government refused to meet with the American envoys and was seeking to extort bribes.

In releasing the diplomatic correspondence from the American diplomats, Adams used X, Y, Z in place of the names of the French envoys. After the dispatches were examined by Congress, even pro French Democratic Republicans were shocked. The Senate promptly voted to release the XYZ dispatches for publication. With public opinion inflamed against France, the Federalists saw gains in the elections of 1798. Thus was born the Federalist slogan, “Millions for defense but not one cent for tribute.” Ultimately, Adams courageously sent a second diplomatic mission to Paris and the Treaty of Mortefontaine was successfully negotiated, plowing the field for the Louisiana Purchase in 1803.

A decade later President Madison withheld information from Congress about French trade restrictions against the United States. Both Presidents Madison and Monroe withheld information regarding the American takeover of territory in Florida.

President Monroe was subpoenaed to appear as a defense witness in a court martial of Dr. William Burton. Rather than appearing in person, Monroe provided testified through written interrogatory answers.

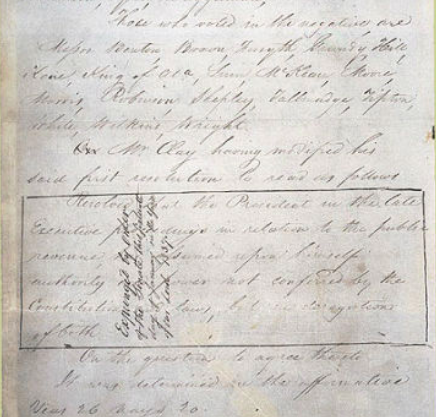

Jackson and the Bank of the United States (1833):

President Andrew Jackson’s dispute with Congress over the Second Bank of the United States remains one of the most heated showdowns between a President and Congress. During the “Bank War” President Jackson (derided as “King Andrew the First”) refused to provide the “paper” he had read to his Cabinet ordering the transfer of funds from the Bank of the United States to smaller state banks.

At the urging of Senator Henry Clay, on December 10, 1833, the Senate adopted a resolution requesting that Jackson release the offending “paper” and explain his instructions to violate the Bank’s Charter. Jackson replied that:

The Executive is a co-ordinate and independent branch of the Government equally with the Senate; and I have yet to learn under what constitutional authority that branch of the Legislature has a right to require of me an account of any communication…made to the heads of departments.…”

When Jackson refused to comply, Clay responded with the following motion to censure Jackson:

Resolved that the President in the late Executive proceedings in relation to the public revenue, has assumed upon himself authority and power not conferred by the Constitution and laws, but in derogation of both.

Three years later, when Henry Clay’s Whig party lost control of the Senate, the Senate Democrats reversed the earlier censure resolution. On January 16, 1837, the 1834 Senate Journal was carried into the Senate chamber. The Jackson censure resolution was marked and interlineated: “Expunged by order of the Senate.” Click here for a photo of the Senate Journal.

It would take another sixty years before another President defiantly refused to cooperate with a Congressional request for records. In 1909, Theodore Roosevelt effectively dared Congress to impeach him when he personally took possession of documents requested by the Senate.

Roosevelt had declined to use the Sherman Act to block the acquisition of the Tennessee Coal and Iron Company by U.S. Steel. A Senate Resolution requested records from the Attorney General pertaining to Roosevelt’s decision. When Roosevelt refused to comply, a Senate committee subsequently requested the same records from the Bureau of Corporations. Teddy Roosevelt boldly took personal custody of the records, explaining that his objective was to ensure that the government’s promise of secrecy to certain parties was upheld. While Roosevelt refused to produce the requested records, he delivered a detailed letter to the Senate describing his reasons for approval of the merger. 43 Cong. Rec. 527 (1909)

Additional reading:

U.S. Congress (1790-1800), The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia (Coxey Toogood)

Images of “Congress Hall”, where Congress met for ten years in Philadelphia (Library of Congress)

Archibald Cox, Executive Privilege, University of Pennsylvania Law Review (1974)

St. Clair’s Defeat v. The Battle of Fallen Timbers

Mark Rozell, “Washington and the Origins of Executive Privilege,” contained in George Washington and the Origins of the American Presidency, edited by Rozell, Pederson and Williams (2000)