MASSACHUSETTS CONSTITUTION OF 1780 – JOHN ADAMS’ BLUEPRINT FOR THE U.S. CONSTITUTION

Historians widely agree that James Madison is the “father of the Constitution.” He is properly credited as a primary drafter of the U.S. Constitution and a leading organizer of the Constitutional Convention in 1787. He was first to arrive in Philadelphia having systematically prepared by studying over 200 books on government and history. A month before the Convention he summarized the results of his research on past republics and confederations in his essay Vices of the Political System of the United States, which identified eleven major flaws with the Articles of Confederation and his proposed solution.

Madison played a critical role as the head of the Virginia delegation. As the author of the “Virginia Plan” Madison framed the agenda for the founders. Madison’s detailed notes on the debates at the Constitutional Convention provide one of the most instructive primary sources of the summer proceedings in Philadelphia’s Independence Hall. The Federalist papers co-written with Alexander Hamilton and John Jay were indispensable for the ratification process. After the Constitution was ratified, Madison was the driving force behind the Bill of Rights which he introduced and shepherded through the first Congress.

Madison played a critical role as the head of the Virginia delegation. As the author of the “Virginia Plan” Madison framed the agenda for the founders. Madison’s detailed notes on the debates at the Constitutional Convention provide one of the most instructive primary sources of the summer proceedings in Philadelphia’s Independence Hall. The Federalist papers co-written with Alexander Hamilton and John Jay were indispensable for the ratification process. After the Constitution was ratified, Madison was the driving force behind the Bill of Rights which he introduced and shepherded through the first Congress.

Yet, Madison’s work as the “architect” for the Constitution was built upon the intellectual foundation provided by John Adams and his Massachusetts Constitution of 1780. As argued below, the Massachusetts Constitution along with Adams’ Thoughts on Government (1776) and A Defence of the Constitutions of Government of the United States (1787) provided an indispensable blueprint for the U.S. Constitution.

John Adams described the Constitutional Convention as “the greatest single effort of national deliberation that the world has ever seen.” Nevertheless, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson were only able participate from a distance, since they were serving as the American ambassadors to England and France when the U.S. Constitution was drafted.

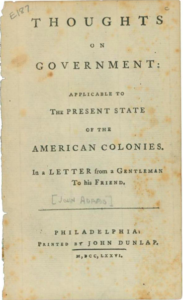

Adams’ Thoughts on Government (1776): During the seminal year of 1776, John Adams outlined the central tenets of his vision for democratic government: separation of powers between three branches of government: executive, legislative, and judicial, with checks and balances. Adams’ proposals were grounded on an in-depth study of enlightenment political theory and history. Adams argued that the colonies were presented with an unparalleled opportunity to form the “wisest and happiest government that human wisdom can contrive.” The constitutional framework articulated by Adams in his Thoughts on Government would later provide the template used to draft the first colonial constitutions and the U.S. Constitution in 1787. Click here for a link to Adams’ essay Thoughts on Government

Adams’ Thoughts on Government (1776): During the seminal year of 1776, John Adams outlined the central tenets of his vision for democratic government: separation of powers between three branches of government: executive, legislative, and judicial, with checks and balances. Adams’ proposals were grounded on an in-depth study of enlightenment political theory and history. Adams argued that the colonies were presented with an unparalleled opportunity to form the “wisest and happiest government that human wisdom can contrive.” The constitutional framework articulated by Adams in his Thoughts on Government would later provide the template used to draft the first colonial constitutions and the U.S. Constitution in 1787. Click here for a link to Adams’ essay Thoughts on Government

The Second Continental Congress in turn agreed with Adams that if independence were to be eventually declared, the colonies would need to establish functioning and independent governments to replace the King. The Second Continental Congress voted on May 10, 1776, to adopt Adams’ resolution recommending that each of the “united colonies” assume the powers of government and “adopt such a government as shall, in the opinion of the representatives of the people, best conduce to the happiness and safety of their constituents in particular, and America in general.”

Based on his reputation, one week after his return from France, Adams was selected in August of 1779 as a delegate to the Massachusetts state constitutional convention. At the convention John Adams was appointed with Samuel Adams and James Bowdoin to the constitution drafting committee. His two committee members did not take long to pick Adams to draft the state constitution. As later described by Adams, he had become,”a sub-sub committee of one.” As he drafted the Massachusetts Constitution, Adams tapped his deep knowledge of the colonies’ experiences under British colonial rule, his exhaustive historical research and expertise in political philosophy, and his proposals set forth in Thoughts on Government. The Massachusetts Constitution written by Adams was ratified on June 15, 1780.

Based on his reputation, one week after his return from France, Adams was selected in August of 1779 as a delegate to the Massachusetts state constitutional convention. At the convention John Adams was appointed with Samuel Adams and James Bowdoin to the constitution drafting committee. His two committee members did not take long to pick Adams to draft the state constitution. As later described by Adams, he had become,”a sub-sub committee of one.” As he drafted the Massachusetts Constitution, Adams tapped his deep knowledge of the colonies’ experiences under British colonial rule, his exhaustive historical research and expertise in political philosophy, and his proposals set forth in Thoughts on Government. The Massachusetts Constitution written by Adams was ratified on June 15, 1780.

The Massachusetts Constitution was the first state constitution to contain a preamble, which introduced the undertaking as a “civil compact” as follows:

The end of the institution, maintenance, and administration of government is to secure the existence of the body-politic, to protect it, and to furnish the individuals who compose it with the power of enjoying, in safety and tranquillity, their natural rights and the blessings of life; and whenever these great objects are not obtained the people have a right to alter the government, and to take measures necessary for their safety, prosperity, and happiness.

The body politic is formed by a voluntary association of individuals; it is a social compact by which the whole people covenants with each citizen and each citizen with the whole people that all shall be governed by certain laws for the common good. It is the duty of the people, therefore, in framing a constitution of government, to provide for an equitable mode of making laws, as well as for an impartial interpretation and a faithful execution of them; that every man may, at all times, find his security in them. Click here for a link to Mass Constitution of 1780:

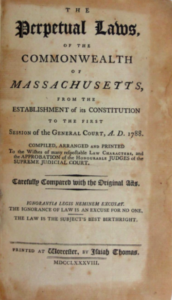

Pictured above is a copy of the Massachusetts Constitution, printed together with the laws of  Massachusetts and the United States Constitution by Isaiah Thomas. Picture here is a copy of the publication, The Perpetual Laws of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Click here for more information about patriot publisher Isaiah Thomas.

Massachusetts and the United States Constitution by Isaiah Thomas. Picture here is a copy of the publication, The Perpetual Laws of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Click here for more information about patriot publisher Isaiah Thomas.

In the decade following the Declaration of Independence, 11 of the 13 state legislatures adopted new constitutions. But at Adams’ urging, Massachusetts used a two step constitutional convention mechanism. Each town elected representatives to a state convention which elevated the Massachusetts Constitution above the status of regular legislation. Adams had recommended that the people must “erect the whole Building with their own hands upon the broadest foundation. That this could be done only by conventions of representatives chosen by the People. . . . ”

The Federalist Papers acknowledged that the U.S. Constitution borrowed directly from the Massachusetts Constitution. By way of example, Federalist 47 cites to the Massachusetts Constitution as follows:

The constitution of Massachusetts has observed a sufficient though less pointed caution, in expressing this fundamental article of liberty. It declares “that the legislative department shall never exercise the executive and judicial powers, or either of them; the executive shall never exercise the legislative and judicial powers, or either of them; the judicial shall never exercise the legislative and executive powers, or either of them. ” This declaration corresponds precisely with the doctrine of Montesquieu, as it has been explained, and is not in a single point violated by the plan of the convention. It goes no farther than to prohibit any one of the entire departments from exercising the powers of another department. In the very Constitution to which it is prefixed, a partial mixture of powers has been admitted. The executive magistrate has a qualified negative on the legislative body, and the Senate, which is a part of the legislature, is a court of impeachment for members both of the executive and judiciary departments. The members of the judiciary department, again, are appointable by the executive department, and removable by the same authority on the address of the two legislative branches. Lastly, a number of the officers of government are annually appointed by the legislative department. Click here for links to Federalist 47; Federalist 73; and Federalist 69.

Nevertheless, arguably the most significant contribution of the Massachusetts Constitution was its very structure and organization. Adams’ blueprint divided the enumerated powers into chapters for each branch of government. It is no coincidence that Articles I, II and III of the U.S. Constitution correspond with Chapters I, II and III of the Massachusetts Constitution.

Unlike the U.S. Constitution, the Massachusetts preamble is followed by a declaration of individual rights. Doing so prioritizes individual rights by placing them at the beginning rather than the end of the constitution. It is also noteworthy that the Massachusetts constitution lists thirty fundamental rights which are broader in many instances than the rights listed in the federal Bill of Rights.

Additional writings by Adams:

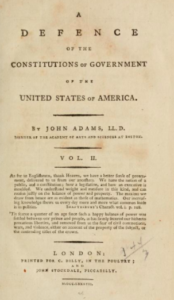

In January of 1787, six months prior to the Constitutional Convention, Adams released the first volume of A Defence of the Constitutions of Government of the United States of America. Written while Adams was serving as ambassador to England, Adams repeated his call for a republic consisting of a balance of powers between the executive, judicial, and legislative powers. In the well researched work Adam cites examples of successful and failed experiments with republican government. Adams explained that the reason why democratic government failed was invariably due to a failure to balance power. By way of example, Adams looked to the English Constitution with its balance of the democratic, aristocratic, and monarchic elements.

Adams wrote that “Power must be opposed to power, and interest to interest.” Madison echoed this sentiment when he explained the mechanism of separation of powers established under the new Constitution in Federalist No. 51, (which famously stated that “[a]mbition must be made to counteract ambition”).

While Adams was a revolutionary, he was also conservative in his instincts. Adams feared that democratic and aristocratic elements were natural enemies which were constantly warring with one another, which explained the chaotic conditions in America during the 1780s. To prevent the rupture of American society, Adams stressed the importance of a government in which a strong executive balancing aristocratic and democratic elements. Click here for a link to A Defence of the Constitutions of the United States of America.

While Adams was a revolutionary, he was also conservative in his instincts. Adams feared that democratic and aristocratic elements were natural enemies which were constantly warring with one another, which explained the chaotic conditions in America during the 1780s. To prevent the rupture of American society, Adams stressed the importance of a government in which a strong executive balancing aristocratic and democratic elements. Click here for a link to A Defence of the Constitutions of the United States of America.

Today, Adams’ 1780 Constitution of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts is the world’s oldest functioning written constitution which famously established a “government of laws, and not of men.” Interestingly, Adams used this phrase in 1775 when he published his Novanglus essay No. 7. Adams’ Novanglus essays were published under his “New England” pen name in the Boston Gazette prior to Lexington and Concord, setting forth Adams’ position on the natural rights of individual Americans which were being impaired by England. Click here for a link to Adams’ Novanglus essays at the Massachusetts Historical Society.

Other contributions by Adams:

As a vocal supporter of independence in the second Continental Congress, Adams was a member of the committee that prepared the Declaration of Independence. While Thomas Jefferson composed the committee draft, Adams’ contribution was also significant. As Jefferson later acknowledged, Adams was the Declaration’s “pillar of support on the floor of Congress, its ablest advocate and defender.” New Jersey delegate Richard Stockton called Adams “the Atlas of independence.” Jefferson called Adams “a colossus of independence.”

As a delegate to the Philadelphia Convention in 1774, Adams nominated Colonel George Washington to be Commander of the Continental Army. He negotiated the Treaty of Paris with Britain that ended the Revolutionary War. Of course, Adams would go on to become the first Vice President, who succeeded Washington as President in 1796.

From 1774 to 1777, Adams served in the Continental Congress. During this time Adams served on ninety committees and chaired twenty. By the end of 1777, Adams was simultaneously working on twenty-six committees and chairing eight. He would later be deployed for France to negotiate military and commercial alliances with Spain and France.

In sum, Adams deserved his nickname the “Atlas of American Independence.” He may also rightly be understood to be the “grandfather” or “architect” of constitutional government, alongside Madison, the “father” of the U.S. Constitution.

Additional reading:

John Adams and the Massachusetts Constitution (mass.gov)

Copied below:

The Perpetual Laws of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, from the Establishment of its Constitution to the First Session of the General Court (1788) compiled by Isiah Thomas E. T. Andrews