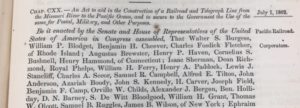

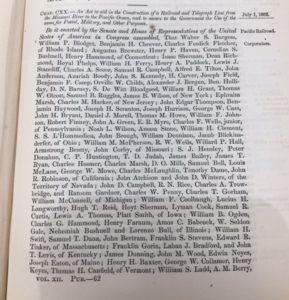

NORTHERN PACIFIC RAILROAD ACT of 1862 (Transcontinental Railroad)

[37th Congress, Chapter 120, 12 Stat. 489-498]

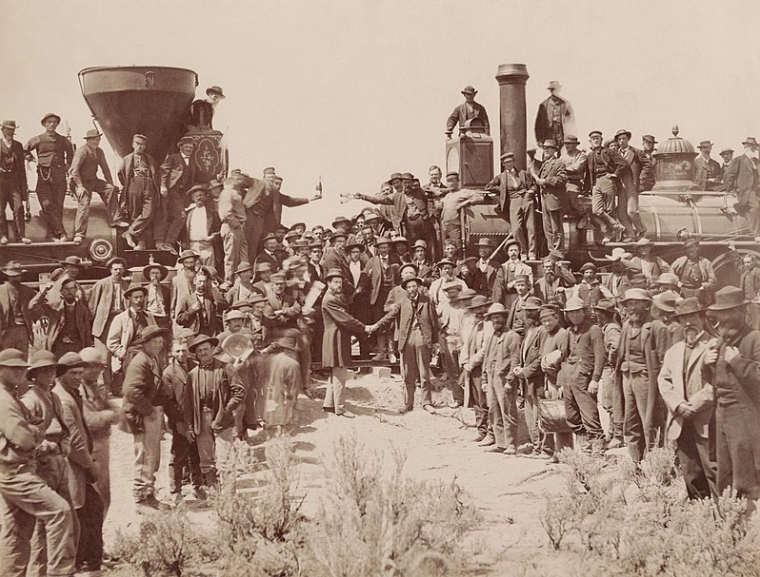

The Northern Pacific Railroad Act of 1862 authorized the Union Pacific Railroad and the Central Pacific Railroad to build a transcontinental railroad and telegraph line from Omaha, Nebraska, to San Francisco, California. Proposals for a transcontinental railroad dated back to 1832, but were mired in political and sectional disputes.

As described by historian Stephen E. Ambrose, “With the improvement of train technology plus the discovery of gold in California, and because of the extreme difficulty of getting to California, there was an overwhelming demand for a transcontinental railroad.”

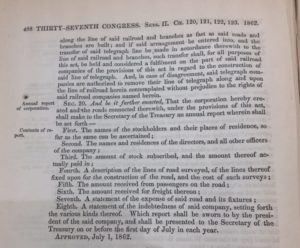

The Act granted a 400 foot wide right of way along the tracks and land for stations. Financing was provided using a government first mortgage loan of $10,000 in Treasury Bonds for each mile of track built over the plains; $32,000 per mile for hilly terrain; and $48,000 per mile through the mountains. The land grants awarded to the Union Pacific and Central Pacific railroads ultimately exceeded 60 million acres and were funded by over $20,000,000 in federal loans. Click here for a link to the Act.

Background: After the South succeeded from the Union, the now dominant Republican led Congress adopted laws that Southern members of Congress had opposed since the 1850’s, including the Morrill Land Grant Collect Act and the Pacific Railroad Act. Congress also created the National Banking Act which established a National Banking System and Comptroller of the Currency to assist with the war effort.

In the years leading up to the Civil War, the proposal for a transcontinental railroad bogged down over which route the railroad should take.In 1855 and in 1859 the Senate had passed bills to provide federal aid to construct three separate transcontinental railway, but the legislation died in the House. Southern states only supported a southern route from New Orleans across the southwest. Without southern opposition, the 37th Congress selected the northern route from Omaha to San Francisco.

The Northern Republicans who supported the bill, including President Lincoln, found legal authority for the federal government to promote railroad construction in the precedent of the Cumberland Road (also known as the “National Road”. Additional constitutional justification was grounded in the Congressional power: 1) to establish post roads, 2) to maintain the armed forces, 3) to provide for the common defense, and 4) to regulate commerce among the states (the interstate commerce clause).

Historian Gabor S. Boritt observed that “The good Whig Lincoln saw commerce as a glue that bound the Union together.” Indeed, the Civil War mobilization effort only undermined the importance of rail transportation, which was an important Northern advantage over the South.

Construction of the Transcontinental Railroad also fit within the Republican party’s (and the predecessor Whig party’s) vision of encouraging free labor to spread westward. By the time the Civil War was over, military mobilization and financial stimulus fostered economic development and expansion in the North.