The People v. Levi Weeks (Part 2)

The first post in this series, The People v. Levi Weeks (Part 1), provided an overview of one of the most notorious murder cases in early American history. Part 1 also provided background about the turn of the 19th Century, including George Washington’s death in December of 1799, a week prior to Elma Sands’ disappearance.

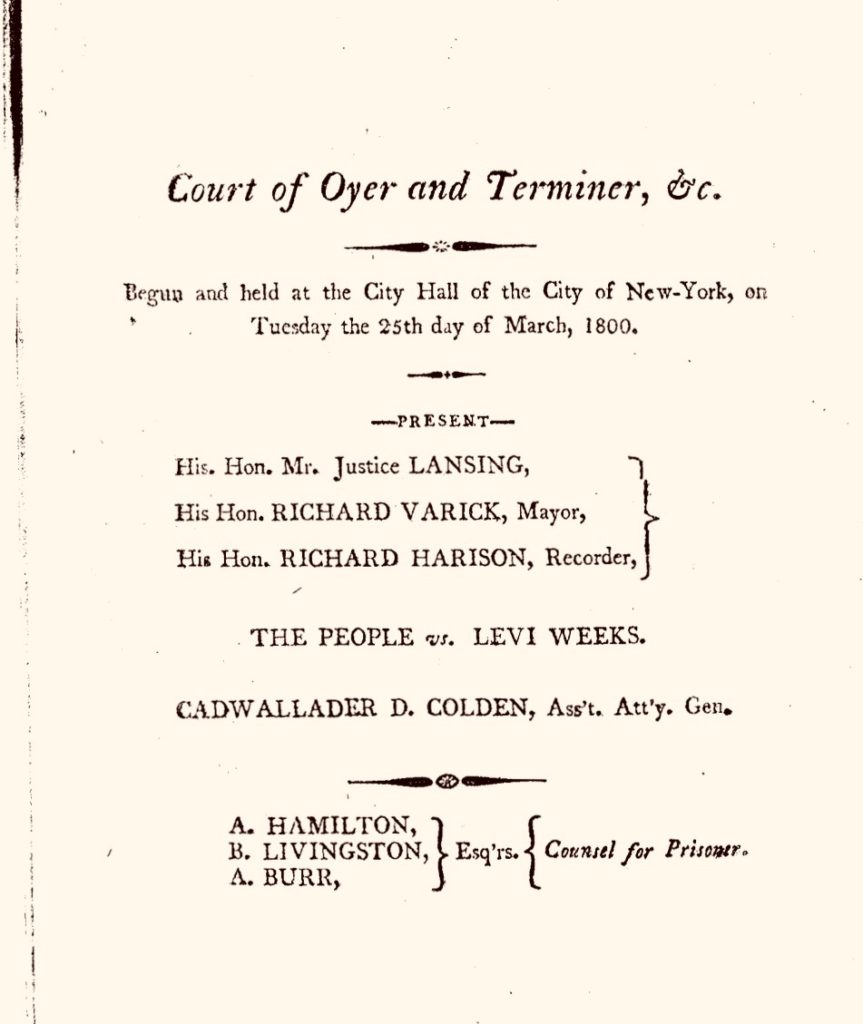

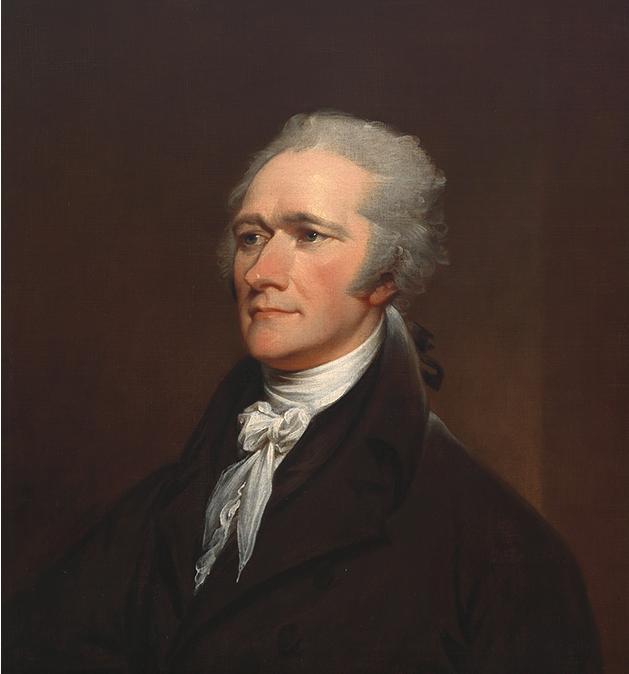

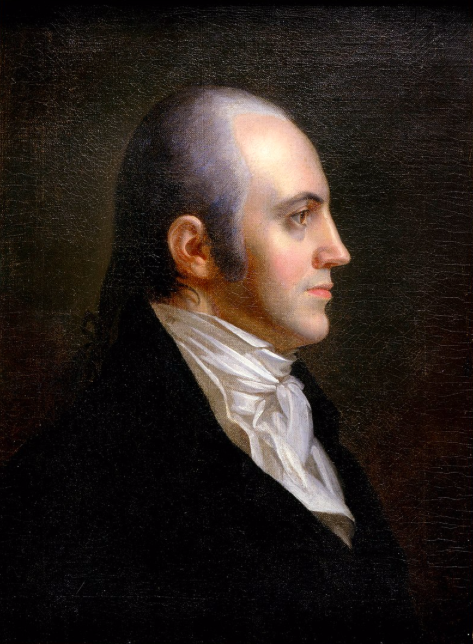

This post, The People v. Weeks (Part 2), focuses on the trial of Levi Weeks and the successful defense by Hamilton and Burr. The marathon trial began three months after Elma Sands’ body was discovered in the Manhattan Well on January 2, 1802. Although popular opinion had convicted Levi in the months leading into the trial, he was fortunate to be defended by one of the greatest legal defense teams in American history: Alexander Hamilton, Aaron Burr (yes – that Aaron Burr) and future Supreme Court Justice Henry Brockhurst Livingston.

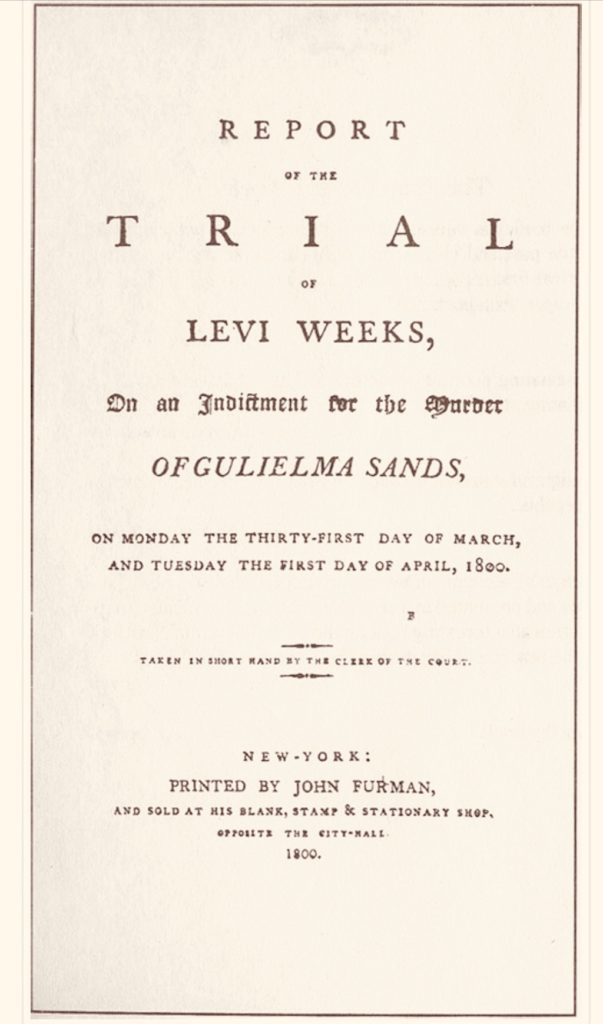

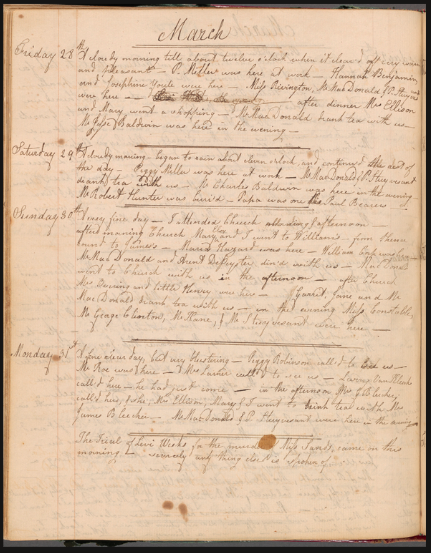

Amazingly, it is possible to delve into actual witness testimony because the Weeks trial was the first case in American history to be fully transcribed. Court Clerk William Coleman transcribed the trial using Byrom’s New Universal Shorthand, a new transcription system that utilized abstract geometric shapes rather than letters. In the years to follow, William Coleman would later become the editor of Hamilton’s newspaper, the New York Evening Post.

The third post in this series, People v. Levi Weeks (Part 3), completes the story after the trial. In some respects, the story of the lawyers, judges and witnesses in the case is arguably as compelling as the trial itself. Part 3 also explores the role of the Weeks case in popular culture. For example, the case continues to fascinate observers, as viewed through the work of literary and artistic giants, Washington Irving, Edgar Allan Poe and Lin-Manuel Miranda.

This post heavily relies on the Coleman transcript, pictured above, which was published in the month following the trial, along with two shorter trial summaries which were quickly published and sold to the captivated public. Click here for a link to William Coleman’s full transcript officially titled the Report of the Trial of Levi Weeks. Click here for James Hardie’s An Impartial Account of the Trial of Mr. Levi Weeks, for the Supposed Murder of Miss Julianna Elmore Sands, at a Court Held in the City of New-York, March 31, 1800. Click here for David Longworth’s more theatrical summary, A Brief Narrative of the Trial for the Bloody and Mysterious Murder of the Unfortunate Young Woman, in the Famous Manhattan Well, which was available for sale within hours of Levi’s acquittal.

Elma Sands (The Victim)

Miss Julianna E. Sands (Elma to friends and family) was last seen alive at approximately 8:00 p.m. on December 22, 1799. Her body was found on January 2 in the Manhattan Well in Lispenard’s Meadow at the then northern boundary of New York City. Her disappearance and likely murder would rivet New York and make national headlines.

Twenty-two year old Elma Sands was an attractive young lady from a respectable Quaker family. Elma had moved to New York City from upstate New York in 1797 to live with her Quaker relatives, Catherine and Elias Ring. The Rings operated a boarding house on Greenwich Street which provided needed housing for the city’s growing population which had doubled in size over the preceding decade to 60,000. The Rings also ran a dry goods shop and millinery operation that employed twenty young women, including Elma and another cousin, Hope Sands. At the time of her disappearance Elma had lived for three years in the Ring boarding house owned by her cousin, Catherine Ring.

Housing was in short supply in New York at the time of Elma’s disappearance. During the Revolutionary War approximately one third of New York City was destroyed during the Great Fire of 1776. Click here for a discussion of the British occupation of New York City, which lasted from 1776 until Evacuation Day in 1783.

New York had served as the nation’s first capital in 1789. The city was a growing commercial and banking center, which overtook Philadelphia as the country’s largest city after the war. At the time of the first census in 1790, New York had a population of 33,000 which would nearly double to over 60,00 in the 1800 census. It was very common for new arrivals to the City to lodge in a boarding house until the could find permanent housing. The Ring boarding house was located in a middle class area populated primarily by Quaker families.

(New York Public Library Digital Collection)

It was common practice for Quakers to display the body of a deceased family member in the parlor of their home for viewing prior to burial. As the crowds increased, Elma’s grieving family decided that the frozen streets of New York would be their parlor, so that all visitors could see Elma and the bruises on her neck and chest. Her decaying body was thus laid out for public view in an open casket for 3 days in a scene witnessed by untold numbers of outraged New Yorkers. In the weeks leading to the trial, newspapers and handbills continued to incite public outrage against Levi Weeks, who was accused of impregnating Elma prior to the murder.

Levi Weeks (The Defendant)

Levi Weeks moved into the Ring boarding house in July of 1799. He was a carpenter by trade who shared a room with his apprentice, William Anderson. One might ask how was a carpenter able to retain such highly regarded lawyers, particularly when Levi Weeks had become “the object of universal abhorrence” in the weeks leading up to the trial. So deep ran the public outrage against Weeks that, “those who dared to suppose him innocent, were very generally considered as partakers in his guilt.”

It is likely that Hamilton agreed to represent Weeks because of the public uproar against a man that Hamilton believed was innocent. At the time, Hamilton was still serving as Inspector General of the army, which was ramping down from a potential war with France. Historians refer to the naval hostilities between the two countries as the “Quasi War,” which involved naval battles in the Caribbean. Click here for a discussion of the Treaty of Mortefontaine between the U.S. and France which paved the way for the Louisiana Purchase.

Another reason why Hamilton took the case was that Levi Weeks was the younger brother of a prominent developer, Ezra Weeks. Indeed, at the time of the trial Hamilton owed money to Ezra Weeks for the construction of the Hamilton Grange, Hamilton’s mansion in Harlem Heights in northern Manhattan. In fact, both Ezra Weeks (the builder/developer) and John McCombs (the architect of Hamilton Grange) would both be key defense witnesses in the case.

Aaron Burr, Hamilton’s rival, was the emerging the Democratic-Republican leader in New York who would soon be elected Vice President. Burr, a former Senator and New York Attorney General, likely joined the defense because in an election year he could not allow Hamilton to monopolize the spotlight in the biggest celebrity trial of its day. It also turns out that Burr had another reason to monitor the trial. Burr was one of the founders of the Manhattan Company, which owned the well where Elma’s body was found.

After it was discovered in the Manhattan Well, Elma’s body was brought to the Ring boarding house. When Levi was asked to identify the body, he inquired if the body had been found in the Manhattan Well. He was arrested pending trial. The criminal indictment charged that Levi Weeks, “not having fear of God before his eyes” and “being moved and seduced by the…devil, beat and abused” Elma Sands and threw her into the well to drown.

Pretrial

After their client was arrested, Hamilton and Burr published an op ed in the New York Daily Advertiser on January 9, 1800 warning New Yorkers not to prejudge the case. The article firmly admonished readers that Levi was innocent until proven guilty. Hamilton and Burr observed that prior to the indictment, Levi Weeks did not fit the profile of a murderer since he had earned a solid reputation as a “moral, sober, industrious, amiable” young man with “no conceivable temptation to perform such an atrocious action.”

Pre-viewing their defense, the op ed explained that the rumored marriage between Elma and Levi was merely unsubstantiated hearsay. As for motive, the autopsy proved the Elma was not pregnant. The editorial also challenged the allegation that a crime had been committed at all, as Elma “had several times been heard to utter expressions of melancholy, and throw out threats of self-destruction, particularly the afternoon before.” Levi’s fate should thus be decided by the “unprejudiced voice of an impartial jury.”

Witnesses were anticipated to testify that Elma went out for the evening at around 8:00 to get married to Levi. He returned after 10:00. She didn’t. Levi’s alibi would place him at his brother’s house for dinner. Recognizing that timing would play a prominent role in the case, both the prosecution and the defense tested how long it would take a sleigh to travel from the Ring boarding house to the Manhattan Well along Greenwich Street and then return to Ezra Weeks’ house along Broadway. Both sides agreed that the round trip took 15 minutes.

As described by Elizabeth Bleeker in her diary entry on March 31, “The trial of Levi Weeks for the murder of Miss Sands, came on this morning scarcely anything else is spoken of.” Click here for Bleecker’s diary which was digitized by the New York Public Library. New Yorkers will correctly recognize that Bleecker Street in Greenwich Village is named after Elizabeth’s father, a leading stock broker, Anthony L. Bleecker. By 1818, the Bleecker family held four of the twenty-eight seats on the New York Stock Exchange. Perhaps one of the reasons that Elizabeth was following the case was because her father’s signature appears on the original list of subscribers for the Manhattan Company.

Opening of the Trial and Jury Selection

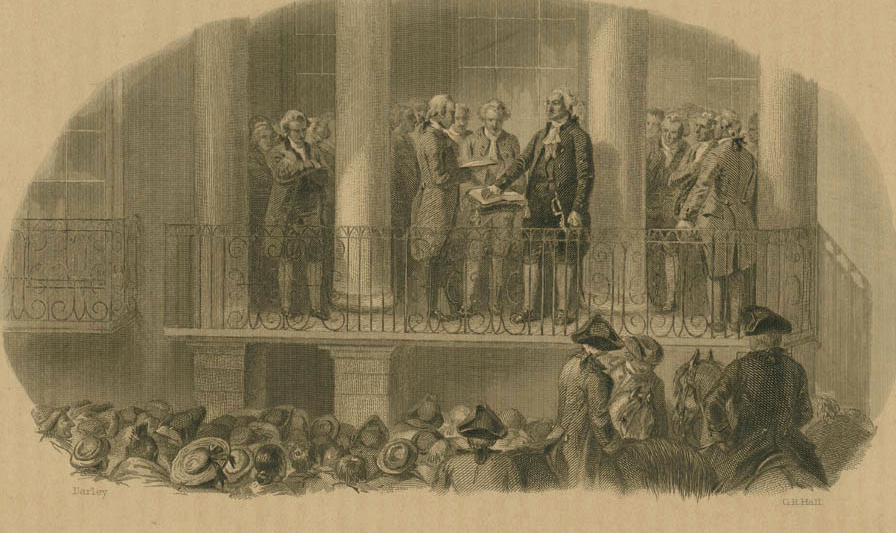

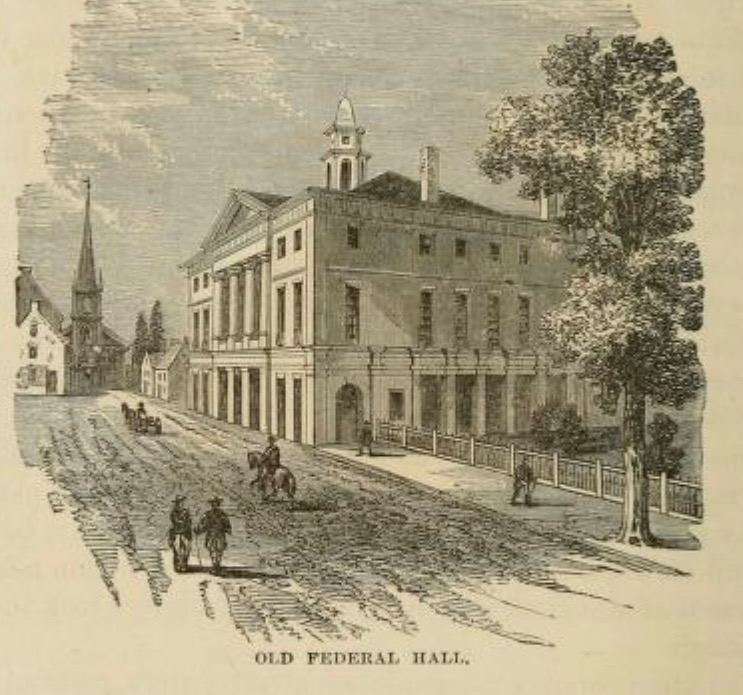

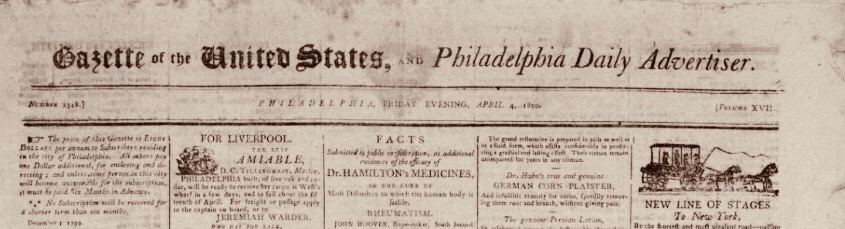

The trial began at 10:00 “in the forenoon” on March 31, 1800 before the New York Court of Oyer and Terminer. The long since abandoned French terminology signified that the court handled serious murder and felony cases. The trial was held at City Hall on Wall Street, otherwise known as Federal Hall, where the first Congress met a decade earlier in 1789.

Large crowds gathered around City Hall to view the trial. More crowds trailed behind Levi Weeks as he was escorted from jail to the courthouse by constables and a brigade of volunteer citizen guards. Those who were unable to enter the building chanted within earshot of the jury for Levi Weeks to be crucified. The mob of spectators squeezing into the courtroom made it “somewhat difficult at first for the court to proceed to business.”

One observer recorded that “the concourse of people was so great as was never before witnessed in New York.” Of course, this opinion was debatable as George Washington was inaugurated on the second floor balcony of the same building before enormous crowds in 1789.

A panel of thirty-four jurors was assembled. Unlike today, where the jury selection process is dictated by lawyers, in the 18th Century the defendant was in charge of jury selection. Interestingly, this was one of the few opportunities for a defendant to speak. A criminal defendant’s testimony was not permitted as the defendant was deemed to be biased in his/her own defense.

The clerk addressed Levi Weeks:

Levi Weeks, prisoner at the bar, hold up your right hand, and hearken to what is said to you. These good men who have been last called…are those who are to pass between the People of the State of New-York, and you, upon your Trial of Life and Death: If, therefore, you will challenge them…your time to challenge is, as the come to the book to be sworn, and before they are sworn you will be heard.

As the name of each potential juror was read aloud, Levi had the opportunity to strike them. Weeks challenged eleven jurors. Other jurors, who were Quakers, asserted that “I am a Friend.” Based on their religious inability to take an oath they were also excused. All twelve of the jurors who were eventually selected were businessmen of one kind or another. This limited jury composition was the result of a requirement that only male landowners with property worth at least $250 (approximately 1 year’s wages) were permitted to serve on a jury.

Conflicting Theories of the Case

The prosecution lacked direct evidence that Levi Weeks committed the murder. Absent eyewitness testimony connecting Levi to the crime, the largely circumstantial case required Prosecutor Colden to weave together a narrative to explain how and why Weeks killed his fiancee. This task would require the testimony of dozens of witnesses.

According to the prosecution, Weeks seduced and murdered Elma to avoid marriage. This prosecution theory was based on Elma’s cousins’ understanding that the couple left together at 8:00 on December 22 to surreptitiously get married. While the couple were not seen leaving together on the night in question, there would be strong testimony that the couple shared a secret romance. Further supporting the prosecution’s theory was Levi’s behavior after Elma didn’t return to the boarding house. In particular, Levi was “pale and much agitated” when he arrived home that night. Moreover, when Levi was asked to identify the body on January 2, he seemingly knew where Elma had been found. Other witnesses would testify that Levi was seen around the well, probing it, in the days prior to the murder. Additional witnesses heard screams near the well on the evening of December 22, which would undermine the suggestion that Elma had committed suicide..

By contrast, the defense disputed that Levi and Elma were engaged. Thorough cross examination by Hamilton would expose the credibility issues with several prosecution witnesses. For example, the testimony of an old woman who was “aged and very infirm” was unreliable. The prosecution theory assumed that a crime had been committed. The defense theorized that Elma was depressed and may have committed suicide, as she had previously threatened.

Hamilton and Burr would also produce multiple alibi witnesses that on the evening of December 22, Levi was having dinner with his brother and preparing for the next day’s work. It would also turn out that the Ring boarding house was not as respectable as it first appeared. If Elma was romantically involved with multiple lovers (including Elias Ring), there would be several suspects with their own reasons and opportunity to commit the crime. More importantly, another resident of the boarding house, “Mad Croucher,” had also been behaving suspiciously by spreading rumors about Levi Weeks.

Opening Statement by the Prosecution

In his opening remarks, Prosecutor Cadwalader David Colden acknowledged the distinguished opposing counsel representing Mr. Weeks. Colden humbly described the defense team as “vastly my superiors in learning, experience and professional rank.” Despite the prosecution’s imbalance compared to the defense team, Colden asserted that his job was merely to offer the truth:

…The prisoner has thought it necessary for his defense, to employ so many advocates distinguished for their eloquence and abilities, so vastly my superior s in learning, experience and professional rank….But gentlemen, although the abilities enlisted on the respective sides of this case are very unequal, I find consolation in the reflection, that our tasks are so also. While to my opponents it belongs as their duty to exert all of their powerful talents in favor of the prisoner…I ought to do no more than offer you …the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth.

Colden offered that Elma was “virtuous and modest” until her “fatal acquaintance” with the prisoner. Colden described Elma as “always of a cheerful disposition, and lively manners, though of a delicate constitution.” “We expect to prove to you that the prisoner won her affections…and deluded her…under the pretense of marrying her” before he “carried her away to a well in the suburbs of this city and there murdered her.”

Coleman continued:

We shall produce a number of witnesses, who, between the hours of 8 & 9 of the evening of the 22d of December, heard, from about the place of the well, the voice of a female crying murder, and entreating for mercy. It will be shown to you, gentlemen, that there was the track of a single horse sleigh, which we shall prove that at some time between the Saturday night before, and Monday morning succeeding, must have come out of Greenwich street, and passed in a very extraordinary manner near the brink of the well…

We shall then show you that Mr. Ezra Weeks, the brother of the prisoner was the owner of a single sleigh, and a dark horse, and that the prisoner had access to it when he chose, and we shall produce to you such testimony, as we suppose will satisfy you that this horse and sleigh was taken out of the yard of Ezra Weeks, about 8 o’clock in the evening of the 22d of December, and was returned again into the yard in less than half an hour.

You will see, gentlemen of the Jury, that we have only circumstantial evidence to offer to you in this case, and you must also perceive that from its nature it admits of no other. I shall, however, reserve my remarks upon this subject, for a future stage in the cause; and shall, without delaying you longer, proceed to call the witnesses. Coleman transcript at p. 12-18.

Today, both sides in a trial present opening statements at the beginning of a case. By contrast, in the Weeks trial the prosecutor’s opening statement was followed by witness testimony and vigorous cross examination by the defense. While the identity of the defense attorneys is not clear on each page of the Coleman transcript, newspaper articles and other summaries make clear that Hamilton was responsible for most of the cross examination. Burr is believed to have initiated the opening argument for the defense discussed below.

Opening Statement by the Defense

Burr began the defense with the following opening statement (as copied from the Coleman transcript):

Gentlemen of the Jury, THE patience with which you have listened to this lengthy and tedious detail of teftimony is honorable to your characters. It evinces your solicitude to discharge the awful duties which are imposed upon you, and it affords a happy preface, that your minds are not infected by that blind and undifcriminating prejudice which had already marked the prifoner for its victim.

…I know the unexampled induftry that has been exerted to destroy the reputation of the accufed, and to immolate him at the shrine of perfection without the solemnity of a candid and impartial trial….We have witneffed the extraordinary means which have been adopted to enflame the public puffins and to direct the fury of popular resentment against the prifoner. Why has the body been exposed for days in the public greets in a manner the moft indecent and fhocking.” Coleman Transcript at p. 64

After acknowledging the “rumors” “excitement” and public “condemnation” against Weeks, Burr admitted that it “requires some fortitude to withstand them.” Burr then pivoted to discuss Weeks’ relationship with Elma. According to Burr:

Notwithstanding there may be testimony of an intimacy having subsisted between the prisoner and the deceased, we shall show you that there was nothing like a real courtship, or such a course of conduct as ought to induce impartial people to entertain a belief that marriage was intended; for it will be seen that she manifested equal partiality for other persons as for Mr. Weeks. It will be shewn that she was in the habit of being frequently out of evenings, and could give no good account of herself; that she had at some time asserted that she had past the eve|ning at houses, where it afterwards appeared she had not been.

Addressing the use of circumstantial evidence, Burr cautioned the jury that they should carefully consult their consciences before condemning an innocent man to death. Burr also explained that the prosecution’s “chain” of circumstantial evidence must either “hang together” or the whole fabric “will tumble down”:

If this doctrine of presumptive evidence is to prevail, and to be sufficient to convict, what remorse of conscience must a juror feel for having convicted a man who afterwards appears to be innocent. In cases depending upon a chain of circumstance, all the fabric must hang together or the whole will tumble down. We shall, however, not depend altogether on the weakness of proof on the part of the prosecution, we shall bring forward such proof as will not leave to you even to balance in your minds, whether the prisoner is Guilty or Not—from even that burden we shall relieve you…..

Before concluding, Burr addressed perhaps the most troubling piece of evidence against Weeks. It was true that Weeks seemingly knew where the body was found when he was asked to identify the body.

Burr explained that “the expression ascribed to the prisoner” [Weeks’ inquiry whether the body was found in the Manhattan Well] “will be satisfactorily accounted for, by proving to you that he had been previously informed that the muff had been found there, and it was therefore natural to enquire if the body was not found there also.”

Burr concluded: “If, gentlemen, we show you all this, you will be able to say, before leaving your seats, that there is nothing to warrant you in pronouncing the prisoner Guilty.”

According to the New-York Daily Advertiser: Mr. Burr opened the defense with perspicuity and force, as he disentangled every circumstance of perplexity; tore away the suspicions that had obstinately hung upon the public mind…If the deceased was murdered, this at least was not the man.”

Invocation of “the Rule”, Evidentiary Objections, Hearsay & Legal Precedents, including Woodcock’s Case

The prosecution’s first witness was Catherine Ring, Elma’s slightly older cousin who co-owned and operated the Ring boarding house with her husband, Elias Ring. When she was called to the witness stand Catherine announced that she was a Quaker. Catherine therefore declined to take an oath, as was her right. Instead, she solemnly “affirmed” her presence in the court.

Prior to any testimony from Catherine, the defense “invoked the rule.” In other words, the defense moved the court to require Catherine’s husband, Elias Ring, to leave the court room during his wife’s testimony. Doing so potentially raised the following question in the mind of the jury: “Why couldn’t the husband hear his wife’s testimony?” Judge Lansing ordered Elias to vacate the chambers, indicating to Levi and his defense team that the prisoner had “a right to it of course, if he requested it.”

Catherine began her testimony explaining that Levi came to reside at the Ring boarding house in July of 1799. Before she could complete her second sentence, the defense quickly objected. Catherine began to testify that Elma “asked me…” but she was “stopped by counsel for the prisoner, who prayed for an opinion from the Court, whether any declarations of the deceased were admissible as evidence.”

The defense admitted that dying declarations of a murder victim were sometimes permitted, “but it was only when they were made after the fatal blow.” In other words, the defense argued that hearsay testimony by a deceased third party needs to be a “dying declaration” made under apprehension of death.

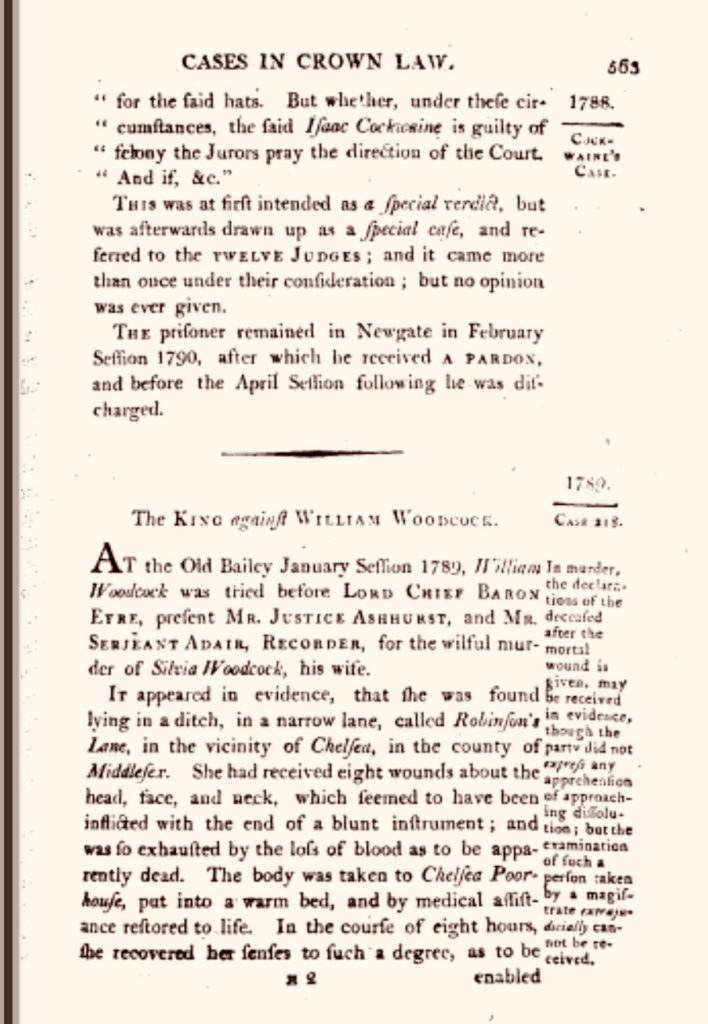

Prosecutor Colden insisted that such testimony was proper. Colden argued that Elma left the house on the night of December 22 and that Catherine’s testimony was “the only way” to discover Elma’s mental state. Colden further argued that “this was one of those cases were evidence was to be admitted upon the necessity of the thing.” To support his argument, Colden cited several precedents: 4 State Trials 487, Leach’s Cases, 2 Bacon 563, and Skinner’s Reports 402.

Defense attorney Henry Livingston argued that the Woodcock’s case (which was reported in Leach’s Cases pictured below) “was in opposition to the principle” announced by the prosecution. Aaron Burr added that the hearsay exception relied upon by the prosecution was confined to “cases in extremis, after the fatal blow.” Burr also suggested that much of Colden’s authority was decided in Scotland and “could not be considered authority here.” Judge Lansing agreed with the defense, instructing Catherine to suppress “whatever Elmore (Elma) had said to her.”

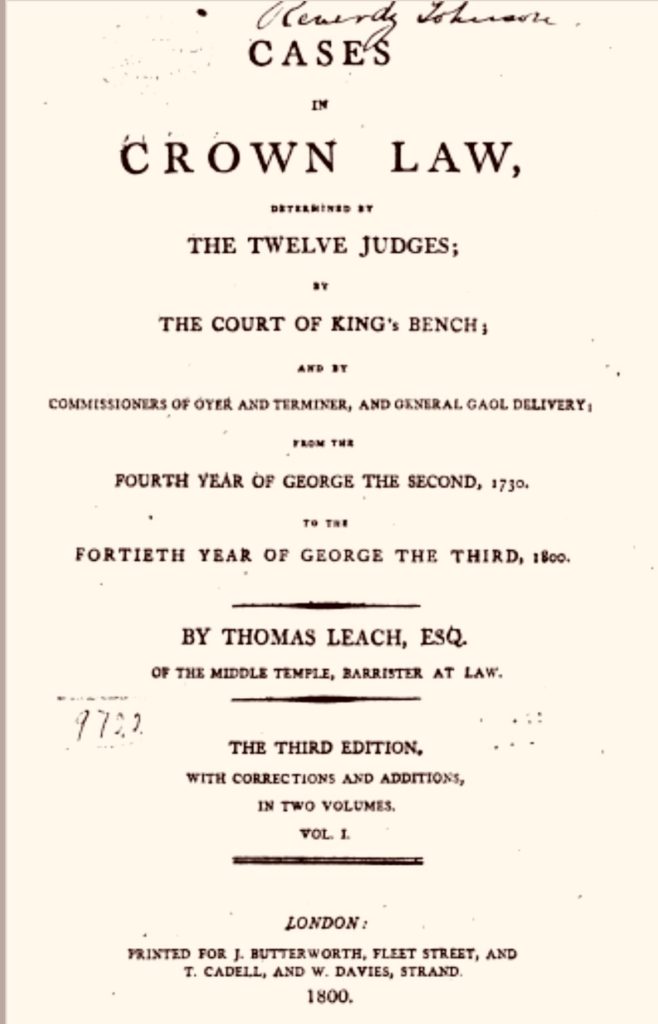

Click here for Thomas Leech, Cases in Crown Law, Volume I (3rd edition, 1800).Click here for Thomas Leach, Cases in Crown Law, Volume 2 (3rd edition, 1800). Woodcock’s case, which is pictured below can be viewed beginning on page 565 of volume 2. Hamilton and Burr argued that Woodcock’s case cited by the prosecution actually supported the defense hearsay objection.

Testimony highlights:

The following highlights merely scratch the surface of the parade of witnesses who testified in the case.:

- Catherine Ring and her younger sister, Hope Sands, testified that Elma left the boarding house with Levi. On cross examination they conceded that they were not positive, since they only heard Levy in the lobby and did not see the couple leave together.

- Catherine and Hope thought that Elma was in good spirits when she left the boarding house on the evening of December 22 at 8:00.

- Catherine’s husband, Elias Ring, testified that, “[Elma] was as cheerful and gay, as I ever saw her.”

- By contrast, according to the Rings, Levi Weeks returned alone at 10:00 “looking pale and agitated.” Later, when Elias asked Weeks about Elma’s disappearance, “he appeared as white as ashes and trembled all over like a leaf.”

- As described above, evidence that Elma had confided in her cousins (Catherine and Hope) that she and Levi were secretly engaged to be married on the evening of December 22, was suppressed by Chief Judge John Lansing.

- Some witnesses opined that they may have seen Weeks using his brother’s sleigh that night on the way to the well. Other witnesses testified that they heard a female voice screaming “Murder” near the well on December 22.

- The defense called several alibi witnesses including Levi’s brother, Ezra Weeks and his wife. The Weeks family and their dinner guests, including architect John McCombs, testified that Levi had spent the bulk of December 22 with them. The defense also provided character witnesses attesting to Levi’s integrity and kindness.

- With regard to Levi’s knowledge that Elma’s body may have been found in the Manhattan Well, Ezra testified that Levi learned that Elma’s muff and a handkerchief had been found in the well based on discussions with others.

- Defense witnesses suggested that while Elma was known as a modest and virtuous girl, she was promiscuous and suicidal.

- In addition to calling alibi witnesses, the defense suggested that other suspects were overlooked by the prosecution. Joseph Watkins, a boarder in the room adjacent to Sands, testified that her uncle, Elias Ring, entered and exited her bedroom at all hours of the night. This traffic into Elma’s room was particularly active when Catherine Ring was away for 6 weeks during the Yellow Fever outbreak during the summer of 1799.

- Another boarder, Timothy Crane, testified that while it was true that Levi was close to Elma, he also paid an equal amount of attention to Hope Sands, Elma’s sister.

- Levi’s apprentice, William Anderson, testified that “I never saw any thing to make me to suppose that my master was more particular in his attentions to Elma, than to the other two, Margaret and Hope.”

- Crane recounted that Elma was “of a melancholy make.” If she would sometimes pass a joke, it seemed forced. Crane testified that he once overheard a troubling conversation between Elma and Dr. Snedecher: “she asked him for Laudanum, and he offered to give her some if she would let him drop it into her mouth, which she consented to, and he dropt a number of drops into her mouth which surprised us all, she said she wished she had a phial full she would take it.” Unlike the Rings, Crane did not think Levi’s behavior or demeanor was unusual.

- The defense also identified witnesses claiming to have seen another boarder, Mad Croucher, near the well on the night that Elma disappeared. Croucher’s conduct was also suspicious as he spent considerable amounts of time spreading stories of Levi’s guilt.

- Croucher, “a shady salesman of ladies’ garments,” admitted during cross examination that he had quarreled with Levi Weeks prior to Elma’s disappearance.

Waiver of Defense Closing Argument & Jury Instruction

Two days of extensive testimony by 55 witnesses finally concluded at 2:30 a.m. (given the late hour it was actually the morning of the third day of the trial). Prosecutor Colden informed the judge that he had been without “repose” for over 44 hours and was “sinking” from exhaustion. Colden requested that the jury be sequestered for a second night and that closing argument be postponed until the morning.

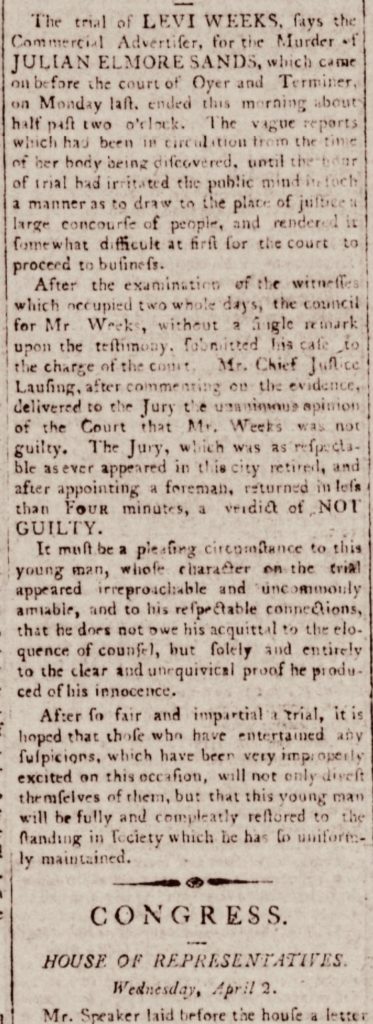

On behalf of the defense, Alexander Hamilton waived closing argument to allow the case to proceed directly to the jury. Hamilton asserted that the defense case could rest on its evidence without “labored elucidation.” As reported by the New-York Daily Advertiser, the fact that Hamilton had forgone closing argument was powerful evidence of innocence. “By the evidence of the facts alone is this young man’s innocence completely established. Not a single doubt remains on the mind of any person who was present at trial.”

Chief Judge Lansing indicated that it was “too hard to keep the jury together another night without the conveniences necessary to repose.” The judge proceeded to charge the jury that in the opinion of the court, there was was insufficient evidence to convict.

Judge Lansing summarized the evidence observing “that in this case it was not pretended that positive proof of the commission of the murder by the prisoner was attainable but it had been attempted to prove his guilt by circumstantial evidence.” After sifting through the testimony, the judge proceeded to charge the jury that in the opinion of the court, there was was insufficient evidence to convict. This judicial colloquy essentially instructed the jury to acquit, stopping just short of ordering an acquittal.

After selecting a foreman, the jury quickly acquitted Levi after only four to five minutes of deliberations. Thus, at 3:00 am the jury rendered verdict. NOT GUILTY.

The New-York Daily Advertiser admitted that everyone in the court had come “more or less impressed with the idea that he was GUILTY…[but] were, as soon as the verdict NOT GUILTY was given, just bursting into involuntary and exulting acclamations.”

Interestingly, the jury selected Simon Schermerhorn, “the most humbly employed of their group,” as their foreman. It is also worth mentioning that Schermerhorn bore an old Dutch name from the City’s past. Perhaps the jury recognized that their decision would not sit well with the public at large who had already convicted Levi Weeks before the trial.

Summaries by Hamilton Biographers:

Historian and Hamilton biographer Henry Cabot Lodge also discussed the case. In Lodge’s opinion:

To any one who reads the report it is obvious that no other verdict was possible. The prosecution failed to show that Weeks had gone out with Elma Sands on the 22d of December, and the defense proved an alibi for Weeks on that evening so complete as to put any participation in the murder on his part practically beyond the bounds of possibility.

As described by Lodge, during Hamilton’s “severe” cross-examination of Mad Croucher, the “wretched witness” “stumbled, contradicted himself, and utterly broke down.” Henry Cabot Lodge, The Democracy of the Constitution and Other Addresses and Essays (1916). Of course, biographies of Aaron Burr attribute the masterful Croucher cross examination to their favored attorney.

In 1861, John Church Hamilton published a multi-volume biography of his father entitled a History of the Republic of the United States of America, as Traced in the Writings of Alexander Hamilton and of His Contemporaries (1864). In volume VII at pages 745 to 747, John provides the Hamilton family account of the Weeks trial:

An occurrence had taken place which greatly excited the sympathies of the inhabitants of the city of New York. The body of a female was found in a public well, and a young mechanic of reputable character, who had been her suitor, was suspected of and indicted for the murder. Hamilton was engaged to defend him. A careful investigation left no doubt in his mind of the innocence of the accused, and his suspicions fell upon a principal witness for the prosecution. But the public feeling had been artfully directed against his client, and to overcome its passionate prejudices was a herculean task. The office of defending him was rendered invidious, and, fearing that his talents would rescue the destined victim from their grasp, Hamilton, when he appeared in the court of justice, was regarded by the multitude, in this, the only time of his life, with a dark and sullen animosity. He resolved not merely to secure the acquittal of his client but to place his character beyond all just suspicion.

John Hamilton also notes that Croucher was later convicted of raping a child and pardoned before moving to Virginia where his crime spree continued. Upon fleeing to England, Croucher was executed “for some heinous crime.”

Hamilton’s grandson, Allan Mclane Hamilton also discussed the Weeks trial in his biography, The Intimate Life of Alexander Hamilton (1910). Allan confirmed that Burr made the opening statement and his grandfather interrogated most of the witnesses. Allan described Elma as a “very beautiful girl” who had been “very intimate with Weeks” but also “decidedly promiscuous” with others as well.

Allan described Weeks as follows:

He was in every way an exemplary young man, and the girl’s relatives were loath to believe him guilty; nevertheless, suspicion pointed very strongly, at least, to his knowledge of the fate of Guilielma, if he himself was not actually the murderer. It was known that she was last seen with him upon the night of her death, and their voices were heard in the hallway of the Ring house shortly before she left, never to return. He was almost distraught, but could give no explanation of what had occurred.

Nevertheless, Allan opined that his grandfather “had always believed in the innocence of his client.” Allan also observed that Hamilton “never entered a case simply as an advocate, but that he first convinced himself of the suspect’s innocence, and then went heart and soul into the defense.”

Additional Reading:

Duel with the Devil: the True Story of How Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr Teamed Up to Take on America’s First Sensational Murder Mystery, Paul Collins (2013) (In the opinion of statutesandstories, this book is a good read for both lawyers and lay audiences. The work also contains extensive and well documented footnotes).

Liva Baker, The Defense of Levi Weeks, ABA Journal, June 1977.

Judge John Lansing, Historical Society of the New York Courts

Prosecutor Cadwallader David Colden, Historical Society of the New York Courts

Diary of Elizabeth De Hart Bleecker (New York Public Library)

The Intimate Life of Alexander Hamilton, Allan McLane Hamilton (1910) (Hamilton’s grandson)

Spinning the Law: Trying Cases in the Court of Public Opinion, Kendall Coffey (2010)