Confirmed: Antifederalist Melancton Smith was Brutus

Deep dive into the “Brutus – Melancton Smith Authorship Thesis” (Part 2)

Adam P. Levinson, Esq. & John P. Kaminski, PhD

For over two hundred years historians have universally agreed that Brutus was one of the most important Antifederalist writers. The political discourse between Brutus and Publius helped frame the national debate during the ratification campaign. Publius, the author of The Federalist papers, was identified long ago. Yet, the identity of Publius’ chief opponent has remained one of the longest standing mysteries in American constitutional history. As set forth below, newly uncovered evidence confirms the “Brutus – Melancton Smith Authorship Thesis.”[1]

In mid-January of 1788, Brutus had published ten of what would become sixteen classic Antifederalist essays opposing ratification. On 23 January 1788 Melancton Smith wrote to fellow Antifederalist Abraham Yates, Jr., requesting assistance.[2] Smith indicated that “very little has yet been written” about the “judicial powers” under the proposed Constitution. Smith shared his concern that Article III of the Constitution appears to be framed as to “clinch all of the other powers” which would be extended “in a slow and imperceptible manner” by the courts. Smith also expressed his fear that the Supreme Court would be “totally independent” and “uncontroulable.”[3]

Writing “in haste,” Smith listed a handful of specific questions for Yates to review involving the proposed federal courts.[4] Smith also shared that “we are weak here” and “have not the leisure or ability” to expose all of the defects of the proposed Constitution. Smith asked Yates to confer with Samuel Jones,[5] a well-respected legal authority who was one of the few prominent Antifederalist lawyers in New York. After soliciting Yates’ and Jones’ input, Smith pointed out that “if you have not time to arrange them for publication, they will afford great assistance to some here who will do it.” Shortly thereafter Brutus 11 appeared in print on January 31.[6] The timing and content of Smith’s January 23 letter and the publication of Brutus 11 one week later provides powerful attribution evidence as to Brutus’s identity.

Brutus 11 directly aligns with Smith’s letter to Abraham Yates. As will be set forth below, Brutus 11 addresses the exact questions raised by Smith and repeats the identical concern that the Supreme Court would be “totally independent” and unaccountable. Providing powerful attribution evidence, Brutus 11 flows directly from Smith’s January 23 letter, expressing the verbatim prediction that the “judicial power” would operate in a “silent and imperceptible manner”[7] to subvert the legislative, executive and judicial powers of the individual states. Further “cinching” his identity, Brutus 11 matches Smith’s complaint that “very little has yet been written” about the “judicial power” which Brutus/Smith feared.[8]

Overview of Brutus Attribution

This blog post is the second of a multi-part series exploring the authorship of the sixteen letters of Brutus. The “Brutus – Melancton Smith Authorship Thesis” argues that Brutus was Melancton Smith, Alexander Hamilton’s chief opponent at the New York ratification convention in Poughkeepsie. Part 1 began with an overview of existing scholarship and summarized the new evidence which has been compiled by Statutesandstories.com in collaboration with John P. Kaminski. Part 2 provides an exhaustive review of the evidence summarized in Part 1. Part 3 will continue with a discussion of additional attribution evidence, including alignment between Melancton Smith’s speeches at the New York ratification convention and Brutus. Part 4 explores newly uncovered speeches by Melancton Smith which further confirm Melancton Smith’s identity as Brutus.

Part 2 provides a deep dive into archival evidence spanning Melancton Smith’s career. The “Brutus – Melancton Smith Authorship Thesis” is based on a detailed review of decades of correspondence, pamphlets, legislative history, records of the New York ratification convention, and recently uncovered speeches by Smith. While the disparate records and manuscripts discussed below are believed to provide compelling proof that Melancton Smith was Brutus, it is important to recognize that the Melancton Smith Papers are relatively limited,[9] compared to the historic record for other more famous members of the founding generation. Further complicating Brutus’s historiography is the fact that Melancton Smith died at a relatively early age during a yellow fever outbreak in 1798. Moreover, many New York records were lost in a fire which destroyed portions of the New York State Capitol in 1911.

Much of this work is only made possible after the completion of the monumental forty-seven volumes of the Documentary History of the Ratification of the Constitution (DHRC). Readers are thus advised that Part 2 is not intended to be a quick read. Rather, the goal of Part 2 is to comprehensively set forth detailed and disparate attribution evidence using sources dated prior to the New York ratification convention. Part 3 will focus on detailed attribution evidence primarily arising from Smith’s speeches at the New York ratification convention. Unlike more traditional and reader friendly blog posts, Parts 2 and 3 might best be consumed in digestible installments.

Earlier this year, Statutesandstories released a related seven-part series about the Antifederalist Federal Farmer. Historians have long recognized Brutus and the Federal Farmer as the two most important Antifederalist authors. For decades, the Federal Farmer was believed to have been Richard Henry Lee. In 1974, historian Gordon Wood challenged this longstanding attribution, but did not offer a replacement author. In 1988, John P. Kaminski released a paper arguing that Elbridge Gerry was the Federal Farmer. Click here for a link to the Federal Farmer – Elbridge Gerry AuthorshipThesis (“FEAT”) which surveys newly uncovered evidence that Elbridge Gerry was in fact the Federal Farmer. With Elbridge Gerry confirmed as the Federal Farmer, the field is cleared for Melancton Smith to be recognized as Brutus.

Part 2 is organized into the following categories of attribution evidence:

- Smith’s 1784 pamphlet opposing the holding in the case of Rutgers v. Waddington which made Smith a leading early critic of judicial review;[10]

- the choice of the pseudonym Brutus and Smith’s political rivalry with Alexander Hamilton;

- Smith’s speech to Congress defending New York’s conditional adoption of the impost requested by Congress

- Smith’s two pamphlets as A Republican defending New York’s actions on the impost

- the nexus and political relationship between Smith and New York Governor George Clinton, as evidenced in Charles Tillinghast’s letter to Hugh Hughes dated 27 January 1788;

- logistical considerations which place Smith in Brutus’s shoes.

Part 3 will continue with the following categories of attribution evidence which flow in large part from Smith’s speeches at the New York ratification convention in June and July of 1788:

- Smith’s linguistic fingerprints (words and phrases reoccurring in Smith’s correspondence and speeches) which align with Brutus;

- Brutus’s frequent use of biblical references which aligns with Smith’s biography as an “ardent Presbyterian” and “pillar of his church”;

- Smith’s logical and syllogistic reasoning style which aligns with Brutus;

- Smith’s ardent and abiding opposition to slavery which aligns with Brutus;

- Brutus’s lack of insider knowledge relating to the Constitutional Convention, in contrast to the Federal Farmer;

- Brutus’s intimate knowledge of the workings of the Confederation Congress which aligns with Smith’s service in Congress beginning in 1785.

A handful of introductory observations are useful. Modern historians have variously suggested that Brutus was Robert Yates, Abraham Yates, Jr., John Williams, and Melancton Smith.[11] When evaluating circumstantial attribution evidence, it is argued below that the best attribution evidence is derived from sources written prior to the first Brutus essay on 18 October 1787. While similarities between the sixteen Brutus essays and subsequent speeches delivered at the New York ratification convention (in June and July of 1788) are relevant, such evidence is only marginally useful for attribution purposes.

During the ratification debate, pseudonymous essays were intended to be shared, quoted and republished.[12] The fact that an Antifederalist speech quoted from Brutus merely demonstrates that the delegate agreed with Brutus. This is particularly the case with John Williams, whose convention speeches shamelessly lifted entire passages from Brutus, Cato, Plebeian and Richard Henry Lee, without attribution. In other words, the minimally supported John Williams attribution[13] – which lacks any pre-authorship[14] collaboration – serves as a useful foil to demonstrate the strength of the overwhelming evidence of the Melancton Smith attribution set forth in detail below.[15]

Smith’s opposition to judicial review in Rutgers v. Waddington

In 1784, Alexander Hamilton defended a Tory businessman, Joshua Waddington, in an important but controversial case that litigated the principle of judicial review. The plaintiff, Elizabeth Rutgers, was a sympathetic widow who had fled British occupied New York City during the war. Thereafter, the family brewery was vandalized by the British. Loyalist Joshua Waddington spent several hundred pounds to restore and reopen the business. While operating the brewery during the war, Waddington paid rent to the British authorities. In 1783, two days before the victorious American army entered New York City, a fire destroyed the property. After returning to New York City, Elizabeth Rutgers filed suit as the property owner seeking back rent under New York’s 1784 Trespass Act.

In the case of Rutgers v. Waddington Hamilton represented defendant Joshua Waddington and argued that the Trespass Act violated both the law of nations and the Treaty of Paris.[16] The case established, among other things, the principle that state law is invalid if it conflicts with a United States treaty.[17] In so holding the Rutgers case created an important state court precedent for judicial review and federal supremacy. Chief Justice Marshall would later rely on Rutgers in the seminal United States Supreme Court case of Marbury v. Madison. The same arguments used by Hamilton in the Rutgers case were discussed in The Federalist.

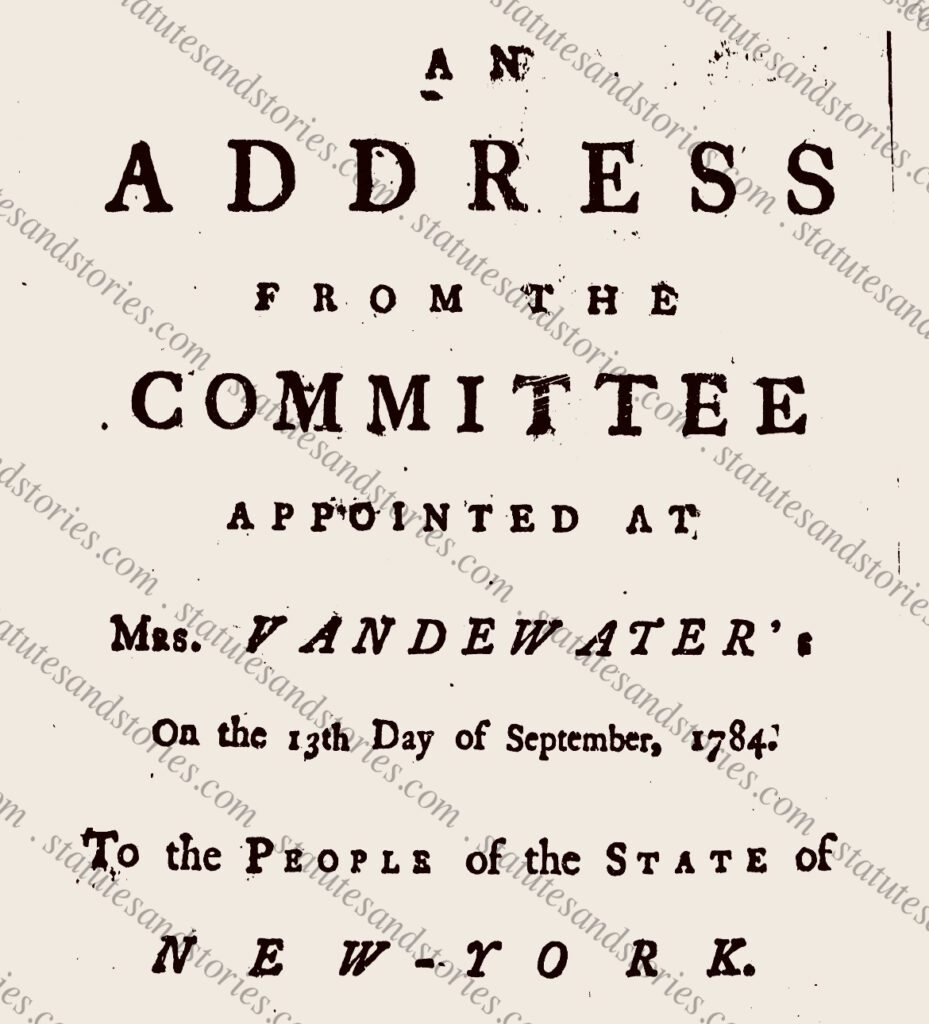

According to Hamilton, the “interpretation of the laws is the proper and peculiar province of the Courts.” In the event of a conflict between state and federal law, “the Constitution ought to be preferred to the statute.”[18] Melancton Smith disagreed. In 1784 Smith was the lead author of a pamphlet challenging the result in Rutgers.[19] The pamphlet, which is easily overlooked by historians, had the innocuous title “An Address from the Committee Appointed at Mrs. Vandewater’s on the 13th day of September, 1784.” Among other things, Smith advocated for the Rutgers case to be appealed by writ of error to the New York Court of Impeachment and Errors. This is the same procedure which Smith supported at the New York ratification convention in 1788.[20] In challenging judicial supremacy under Article III of the Constitution, Brutusused substantially similar arguments advanced by Smith in 1784. In turn, “Brutus’s critique provided Hamilton’s analytic framework” for Federalist 78-83.[21]

In his 1784 pamphlet from Vandewater’s, Smith railed against the dangers of judicial review, which transferred power to judges “who are independent of the people.”[22] For Smith, the ability of a court to set aside legislation was a threat to the “liberties of the people.” As described by Smith, the design of the courts was to “declare laws, not to alter them.”[23]“Such power in the courts would be destructive of liberty, and remove all security of property.”[24]

These same arguments appear beginning in Brutus 11. For example, Smith’s 1784 pamphlet repeatedly warned that the precedent in Rutgers was a threat to “liberty and the security of property.”[25] Brutus 14 aligns with this concern that the federal courts jeopardized “security of property under this constitution.”[26] At the core of Smith’s disagreement with Rutgers was the objection that judges would be “independent of the people.”[27] Likewise, Brutus 15 explained that the constitution is a compact between the people and their rulers. If the government violates the compact, the people have a right to remove them. “[B]ut when this power is lodged in the hands of men independent of the people, and of their representatives, and who are not, constitutionally, accountable for their opinions, no way is left to controul them but with a high hand and an outstretched arm.”[28]

Brutus 15 repeats the same biblical analogy that Supreme Court justices would generally feel themselves “independent of heaven itself”:

There is no power above them, to controul any of their decisions. There is no authority that can remove them, and they cannot be controuled by the laws of the legislature. In short, they are independent of the people, of the legislature, and of every power under heaven. Men placed in this situation will generally soon feel themselves independent of heaven itself.

Particularly problematic for Brutus was the fact that Supreme Court decisions would be unreviewable. Brutus pointed out that judicial supremacy under the proposed constitution was a departure from the procedure in both England and in New York.[29] Brutus 11 begins by mentioning that the proposed judicial power under Article III was “altogether unprecedented in a free country.” The federal courts “are to be rendered totally independent, both of the people and the legislature.” In 1784, Smith had access to writs of error to appeal the Rutgers decision, which he championed in his Rutgers pamphlet. In England, litigants could appeal to the House of Lords, which acted as a court of last resort.[30] Yet, no such procedure would be available under the proposed Constitution. This perfectly explains the motion that Smith made at the New York ratification convention on July 17 “[t]hat all appeals from any Court, proceeding according to the course of the common law, are to be by writ of error….”[31]

Brutus 15 explained that the judges in England, “are subject to correction by the house of lords; and their power is by no means so extensive as that of the proposed supreme court of the union.” British judges “in no instance assume the authority to set aside an act of parliament under the idea that it is inconsistent with their constitution. They consider themselves bound to decide according to the existing laws of the land, and never undertake to controul them by adjudging that they are inconsistent with the constitution.”

Brutus 15 further explained that:

The judges in England are under the controul of the legislature, for they are bound to determine according to the laws passed by them. But the judges under this constitution will controul the legislature, for the supreme court are authorised in the last resort, to determine what is the extent of the powers of the Congress; they are to give the constitution an explanation, and there is no power above them to set aside their judgment.

Other similarities between Smith’s Rutgers pamphlet and Brutus include the following[32]:

- The Rutgers pamphlet and the Plebeian are addressed to the People of the State of New-York. TheBrutus essays are similarly addressed “to the People of the State of New-York” or “to the Citizens of the State of New-York.”

- The first sentence of the Rutgers pamphlet discusses the rights and “the happiness of people who live in a free government.” The same concepts and terms are repeatedly used in the Rutgers pamphlet,[33] by Brutus and in Smith’s convention speeches. For example, the first sentence in Brutus 4 declares that there can be no “free government” when the people lack the power to make the laws under which they are governed. The “happiness of the people” is discussed in the second paragraph in Brutus 4. Brutus 3 and 4 discuss representation and the execution of the laws “in a free government.” Likewise, the first sentence of Brutus 9 declares that the goal of government is to “protect the rights and promote the happiness of the people.” Brutus 9 also discusses concepts of “free government.” Melancton Smith’s July 17, 1788 motion in the state ratifying convention refers to governmental power “in a free government.”[34]

- Brutus 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 9, 15, 16 all use the term “free government,” in many cases repeatedly. Smith mentions principles of “free government” in his first convention speech on June 20, June 21 and June 25, in addition to repeated motions.

- The Rutgers pamphlet uses the phrase “plain and obvious” four times. Brutus 13 also uses this phrase.

- The Rutgers pamphlet discusses “writs of error,” which are mentioned twice in Brutus 14.

- The Rutgers pamphlet refers to the “law of nations,” which is also mentioned in Brutus 14. The Rutgers pamphlet also cites to Grotius, which is also cited in Brutus 11.

- The Rutgers pamphlet uses the adjective “absurd in itself” to describe a disputed position.[35] Brutus repeatedly uses the word absurd in Brutus 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 11, including “the highest degree absurd,” “groundless and absurd,” “very absurd,” and “absurdity.” Smith uses the term absurd in speeches on June 20 and 21.

Brutus pseudonym and Smith’s political rivalry with Alexander Hamilton

The choice of pseudonyms in early American history was strategic.[36] While Brutus doesn’t explain the reason(s) he selected his pen name, several explanations directly connect the Brutus pseudonym to Melancton Smith, including his longstanding rivalry with Alexander Hamilton. The ostensible reason for an Antifederalist to adopt the name Brutus was that Marcus Junius Brutus famously attempted to defend the Roman republic from Julius Caesar on the Ides of March, 44 B.C.E. The Antifederalists no doubt expected that they were likewise defending the American republic. At least four other explanations connect Smith and the Brutus name.

First, Smith was a loyal political lieutenant of Governor George Clinton. Governor Clinton wrote under the pseudonym Cato. Alexander Hamilton is believed by many to have replied to Clinton’s Cato essay, writing as Caesar. Cato appeared in print on 27 September 1787 and Caesar’s attack on Cato followed on 1 October. This timing would have allowed Smith approximately two weeks to select the pseudonym to defend Governor Clinton, when he published his first Brutusessay on 18 October.

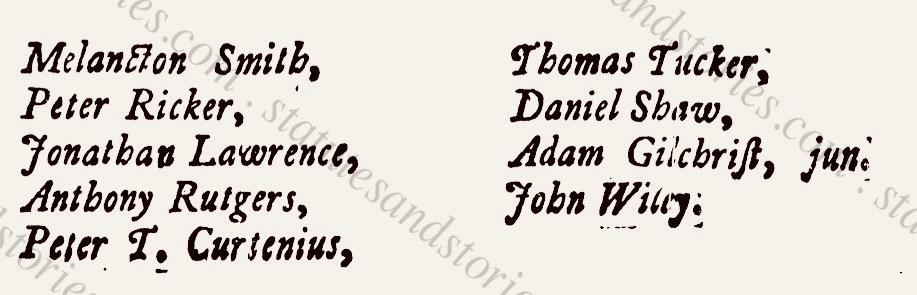

Second, several months earlier, in July of 1787, Hamilton anonymously published a letter in the New York Daily Advertiser highly critical of Governor Clinton. Hamilton took aim at Clinton for improperly attempting to undermine the Constitutional Convention before it had completed its work.[37] Melancton Smith is believed to have defended Clinton in an anonymous essay written to the New York Journal as A Republican in September of 1787.[38] Third, Alexander Hamilton was a great admirer of Julius Caesar. According to a story told by Thomas Jefferson, Hamilton claimed that Julius Caesar was the “greatest man who ever lived.”[39] As described above, Smith was at odds with Hamilton over the Rutgers case dating back to 1784. Their political rivalry would continue during the mid-1780s. The use of the Brutuspseudonym may thus have been selected as a challenge to Hamilton.

Similarly, Smith faced off with Hamilton over New York’s adoption of a federal impost (a proposed federal tariff on imports) in 1786-1787. During the debate over the proposed impost Smith is believed to have authored two pamphlets by A Republican defending New York’s decision in May of 1786 to impose conditions on the impost requested by Congress.[40] It is clear that New York benefited from multistate commerce flowing through New York harbor. When the New York legislature ratified the impost, it reserved the right to collect the impost revenue with its own collectors and stipulated that payments to Congress could be made in New York paper money. Congress, however, rejected New York’s conditional ratification of the impost.[41] This precipitated a national debate over the impost, which became a defining issue in American politics heading into the Constitutional Convention in May of 1787.[42]

In February of 1787, Alexander Hamilton’s delivered what would become a famous speech to the New York Assembly in support of the proposed federal impost.[43] While Hamilton ultimately failed to convince Governor Clinton and his party to ratify the proposed impost without restrictions, New York’s well publicized vote against the impost crystalized the issue for the nation. The impost battle in New York brought into stark relief the defects with the Articles of Confederation following the Annapolis Convention. Hamilton was front and center during this debate. Accordingly, Smith had several overlapping reasons to assume the name Brutus to defend Clinton and/or to challenge Hamilton. As described by William Treanor, “for Hamilton, Brutus was not only a worthy opponent, he was, apparently, a consistent opponent.”[44]

The Impost controversy and Smith’s authorship of the A Republican pamphlets

After America emerged from the Revolutionary War one of the foremost issues facing the nation was the need for Congress to raise revenue. Beginning in 1781 Congress proposed the creation of a five percent tariff on imports (the “Impost of 1781”). For the next seven years the proposed federal impost was at the center of a national debate over Congressional taxing power and state sovereignty. Alexander Hamilton and Melancton Smith squared off on opposite sides of the resulting political battle. While Smith did not leave behind an extensive paper trail he did publish two pamphlets from A Republican in 1786 and 1787 regarding the proposed federal impost and state implementing legislation. Useful “pre-authorship” Brutus attribution evidence can be found in Smith’s two Republican pamphlets, which align with the subsequent publication of several Brutus essays.

By the summer of 1782 every state except Rhode Island had approved the proposed federal impost.[45] Congress tried again in 1783 with a scaled down impost proposal (the “Impost of 1783”). Nevertheless, this time the Impost of 1783 was defeated by New York in May of 1785.[46] As frustration mounted with New York, Congress asked the Empire State to reconsider.[47] A national spotlight focused on the New York legislature in April of 1786 as it revisited the Impost of 1783. Yet, in May of 1786 New York once again effectively rejected the Impost of 1783 by imposing conditions which were expected to be unacceptable to Congress.[48]

In August of 1786, Congress renewed its request for Governor Clinton to reconsider by calling a special session of the New York assembly.[49] Clinton refused.[50] Just as Rhode Island was derided for vetoing the Impost of 1781, New York was now blamed for impeding solutions to the nation’s mounting financial problems. When the regular session of the New York legislature eventually met in January of 1787, newly elected New York Assemblyman Alexander Hamilton was ready.

During the war, Hamilton had written as the Continentalist that “[p]ower without revenue….is a name.”[51] In 1786, Hamilton submitted a petition to the New York legislature advocating in favor of the impost. Hamilton observed that “New York now stands almost alone in a non compliance.”[52] He explained that “[g]overnment without revenue cannot subsist.”[53] Hamilton’s impost petition was printed in the papers. The public was also invited to coffee houses to sign, including Van der Waters, the same location where Smith’s committee met in 1784 to challenge the Rutgers case.

Hamilton was specifically elected to the New York Assembly on a campaign to fight for adoption of the federal impost.[54] On 15 February 1787 he gave a roundly heralded and widely reported speech in favor of New York’s adoption of an unconditional impost.[55] Despite Hamilton’s best efforts, the requested impost failed by a vote of 38-19.[56] As later described by Hamilton, “Impost Begat Convention, ”meaning that the failure to adopt the proposed federal impost gave rise to Constitutional Convention.[57]

As a member of Congress, Melancton Smith was not a passive observer during the impost battle. When Congress debated whether to accept New York’s conditional adoption of the impost in 1786,[58] Smith pointed out that New York was not alone in placing “restrictions & limitations” on the proposed impost. Smith argued that New York’s substantial compliance should be accepted as sufficient.[59] Smith expounded upon this argument when he published his two Republican pamphlets in 1786 and 1787. In August of 1786 Congress asked Governor Clinton to reconsider his decision not to call a special session. During the Congressional debate Smith offered a motion opposing the second request to Governor Clinton. According to Smith “it would involve an interference of Congress” on a question respecting the construction of the New York Constitution upon which Congress has “no right to decide.”[60]

Interestingly, the battle over the impost in the mid-1780s placed Smith and Hamilton on opposite ends of a national debate. To the extent that the Rutgers case was a technical legal question under New York law, the dispute over the impost reverberated nationally. Importantly, the controversy over the impost resulted in two pamphlets and a Congressional speech by Smith which provide the useful “pre-authorship” Brutus attribution evidence. As set forth below, the arguments by Smith involving the impost align with Brutus. Moreover, Smith’s Republican pamphlets and Congressional speech supporting the impost contain the same fingerprints found in his Brutus essays.

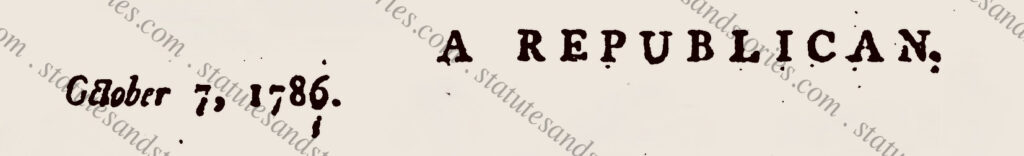

Smith’s speech in defense of the New York’s action on the impost

The purpose of Smith’s speech to Congress in July of 1786 was to defend New York’s partial compliance with the impost. Admittedly Smith’s speech implicates a more narrow set of issues than the broader constitutional questions at issue during the ratification debate in 1788. Nevertheless, Smith advanced a pro-states rights position in 1786 which was consistent with his subsequent Antifederalism. Smith’s impost speech also aligns the detailed discussion of the history of the impost in Brutus 7. Unfortunately, the entirety of Smith’s speech was not transcribed or reported in the newspapers or the Congressional journal. Thankfully, Smith’s outline for his speech – in his handwriting – is preserved in the Melancton Smith Papers in the New York State Library in Albany. As described below, the organization of Smith’s impost speech is particularly useful as it evidences an organizational pattern that repeats over time.

Brutus 1 begins by introducing a “question” which he would be investigating. The third paragraph of Brutus 1 emphasizes that this is “the most important question that was ever proposed to your decision, or to the decision of any people under heaven, is before you.”[61] Likewise the first sentence of Smith’s July 1786 speech begins by reflecting on the “importance” of the subject at hand. Shortly thereafter, Smith frames “the question” as whether substantial compliance by New York will “answer the main end Congress is requiring.” Smith explains that the main end of the impost was to raise money. Smith then reasons that New York’s conditional impost “answers the end which was in view.” This same pattern of argument generally repeats in Brutus, Plebeian, and Smith’s convention speeches.[62]

In the impost speech, Smith uses the following devices and phrases which evidence a consistent and logical argumentation style:

- Smith identifies a question. For example, in the July speech Smith indicates: “the question then is, is this Law such a substantial compl[iance] as will answer the main end Congress had in view….”[63] In some cases, Brutusdescribes the question as an “important question,”[64] “a question of the first importance,”[65] or a “momentous” question.[66]

- Smith evaluates whether the means answer/achieve the end/object/purpose. For example, in the July speech Smith indicates: “If this act provides effectually to raise the money, it then answers the end...”[67]

- Smith asks follow-up questions: For example, in the July speech Smith asks: “Let us now enquire how far the States have granted these.”[68] Interestingly, Brutus and Plebeian always spell the word “enquire” with an “e.” By contrast, Publius variously uses the alternative spelling “inquire” and “enquire.”[69]

- Smith identifies relevant observations: For example, in the July speech Smith observes: “From these observations it appears….”[70]

- Smith connects the dots explaining what has been “shewn” (and/or what the evidence “shews)”: For example, in the July speech Smith explains: “it has been shewn that….” “This shews….”[71]

Historians have repeatedly noted the “logical development”[72] of Brutus’ letters, which were among the “most powerful and well-reasoned Antifederalist writing.”[73] This aligns with first hand descriptions of Smith’s speeches as “acute and logical”[74] and “dry, plain and syllogistic.”[75] Smith’s rhetorical style and use of logic will be discussed at the end of this post, along with his linguistic fingerprints.

A Republican pamphlets

Smith’s notes for his impost speech are undated, but is believed to have been delivered to Congress in July of 1786.[76]Thereafter, Smith published two pamphlets as A Republican which built on Smith’s speech and continued defending New York’s conditional adoption of the impost. Smith’s 1786 speech and subsequent pamphlets are consistent with his position during ratification. In both cases, Smith supported New York’s conditional approval of the impost in 1786 and ratification of the Constitution with conditional amendments in 1788.[77]

Compiled together in Smith’s Republican pamphlets are a variety of impost laws adopted by each state. Smith’s goal was to demonstrate that New York’s impost substantially complied with the request by Congress. Smith also argues that uniformity by the states should not be required by Congress. While the bulk of Smith’s pamphlets is merely a review of comparative legislative provisions and portions of the Congressional record, Smith’s commentary is instructive. In particular, the Republican pamphlets foreshadow Brutus’s focus on the “public good” and reluctance to “part with power.” Perhaps most importantly, the Republican pamphlets help inform Brutus’s understanding that “the most important end of government” is the “proper direction of its internal police.”[78]

Smith explains in the Republican pamphlet that “[a]n enlightened free people will always be cautious how they part with power.” “They will never do it unnecessarily, and will take care to guard against the abuse of it.”[79] This statement by A Republican aligns perfectly with Brutus’s sentiments. At the beginning of Brutus 1, readers are warned that “when the people once part with power, they can seldom or never resume it again but by force.” Brutus emphasizes that the public should “be careful, in the first instance, how you deposit the powers of government.”

Brutus 4 explains that the “object of every free government is the public good.” This aligns with the statement in the Republican pamphlet that the states possess “the right of free deliberation[80] and ought not to be influenced by any other consideration than the public good.”[81] The “public good” is also repeatedly mentioned in Brutus 1, 6, 9, and Smith’s June 21 convention speech. Smith’s focus on the public good also appears in Smith’s draft of the New York circular letter and Plebeian.

According to Brutus 7, “[t]he most important end of government then, is the proper direction of its internal police, and economy,” which is “the province of the state governments.” This aligns with Smith’s observation on the first page of the Republican pamphlet that the imposts adopted by the states reflected the different “conditions, restrictions, and limitations, as their different constitutions and internal police seem to require.”[82]

Brutus 7 contains a wide-ranging discussion of the impost and what Brutus calls the “internal police.” Brutus 7 expresses the following personal opinion which provides what should be deemed strong attribution evidence connecting Brutus and Smith: “My own opinion is, that the objects from which the general government should have authority to raise a revenue, should be of such a nature, that the tax should be raised by simple laws, with few officers, with certainty and expedition, and with the least interference with the internal police of the states.” Brutus 7 also sets forth a history of the impost beginning with the Impost of 1781 and the Impost of 1783.

The phrase “internal police of the states” is also used in Brutus 3 and 6. In particular Brutus 6 mentions the internal police twice, including in the first two paragraph as follows:

It is an important question, whether the general government of the United States should be so framed, as to absorb and swallow up the state governments? or whether, on the contrary, the former ought not to be confined to certain defined national objects, while the latter should retain all the powers which concern the internal police of the states?

….The question therefore between us, this being admitted, is, whether or not this system is so formed as either directly to annihilate the state governments, or that in its operation it will certainly effect it. If this is answered in the affirmative, then the system ought not to be adopted, without such amendments as will avoid this consequence. If on the contrary it can be shewn, that the state governments are secured in their rights to manage the internal police of the respective states, we must confine ourselves in our enquiries to the organization of the government and the guards and provisions it contains to prevent a misuse or abuse of power.

Brutus 11 discusses the “internal police” with regard to the judicial branch:

Much has been said and written upon the subject of this new system on both sides, but I have not met with any writer, who has discussed the judicial powers with any degree of accuracy. And yet it is obvious, that we can form but very imperfect ideas of the manner in which this government will work, or the effect it will have in changing the internal police and mode of distributing justice at present subsisting in the respective states, without a thorough investigation of the powers of the judiciary and of the manner in which they will operate.

In sum, Smith’s Republican pamphlets and his July speech to Congress align with and presage the positions taken by Brutus.

Logistical considerations which place Smith in Brutus’s shoes

The Constitution was signed in Philadelphia on September 17. It became public the next day when it was printed in the Pennsylvania Evening Chronicle on September 18 and the Pennsylvania Packet on September 19.[83] Almost exactly a month later the first of sixteen[84] Brutus essays appeared in the New York Journal on October 18. As a leading Antifederalist member of Congress and Governor Clinton’s loyal lieutenant, Melancton Smith was ideally situated to become Brutus.

The political alignment of Federalists and Antifederalists in New York “mirrored disputes which had long existed in New York politics.”[85] Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, Robert R. Livingston, Philip Schuyler and their Federalist colleagues were largely the party of “commercial and professional classes” in New York City and the southern counties who were aligned with New York’s large landholders and “conservative Whigs.” By contrast, the Antifederalists led by Governor George Clinton tended to be yeoman small farmers and tenant farmers who considered themselves to be “popular Whigs.”[86] Compared to their Federalist counterparts, Antifederalist leaders were “politicians without influence and connections, and ultimately politicians without social or intellectual confidence.”[87] Melancton Smith, Abraham Yates, Jr., Robert Yates, and John Lansing, Jr., were among the new breed of post-war New York politicians who had “bypassed the social hierarchy in their rise to political leadership” but “lacked those attributes of social distinction and dignity that went beyond mere wealth.”[88]

Congressman Melancton Smith was one of three New York delegates[89] who were present when Congress debated the Constitution from September 26th to 28th. All three supported efforts by Antifederalists in Congress to attach a bill of rights to the Constitution before sending it to the states. Smith’s own handwritten notes of the Congressional proceedings in September indicate, not surprisingly, that he was an early and leading Antifederalist. For example, Smith seconded Richard Henry Lee’s motion on September 27 to acknowledge the limitations on the power of Congress to amend the Articles of Confederation. The behind-the-scenes compromise reached in Congress resulted in a quiet, ministerial transmittal of the Constitution to the states without approbation or disapproval.[90] Melancton Smith’s notes of the secretive deliberations in Congress are the best source of this early, tense debate between Federalists and Antifederalists.[91]

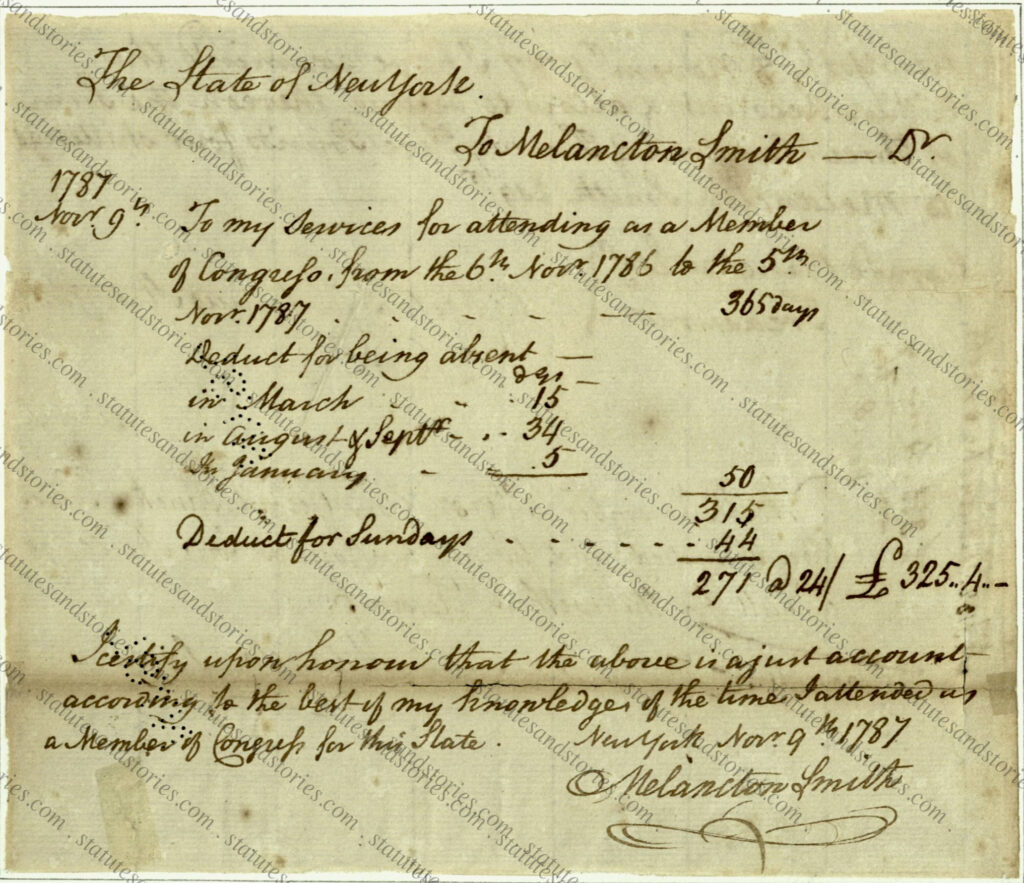

Financial records indicate that Smith was paid for his congressional service through 5 November 1787, even though Congress failed to obtain a quorum in late October and early November. As a result, Smith had free time to confer with Antifederalist colleagues in New York City, including Richard Henry Lee and Elbridge Gerry. As of 4 October 1787 Smith had already formulated objections to the Constitution and had staked out his position in opposition to the unamended constitution.[92] Moreover, similarities in the early Brutus and Federal Farmer essays are consistent with Smith and Gerry collaborating in New York City with Richard Henry Lee, before Gerry[93] returned home to Massachusetts and Lee returned to Virginia.

Smith was from Dutchess County but moved to New York City circa 1784.[94] Based on his residence in New York City, Smith had convenient access to Thomas Greenleaf, the publisher of the New York Journal, which printed Brutus and other Antifederalist essays. When he wasn’t meeting in Congress, Smith remained in contact with Antifederalist allies in other states, including Samuel Osgood and Nathan Dane who played an important role strategizing with Smith during the New York ratification convention.[95] Surviving correspondence also indicates that Smith was in communication with Antifederalists in New York, including Abraham Yates and Samuel Jones. Smith was also active with the New York Federal Republican Committee, which organized Antifederalists and distributed Antifederalist publications. Working closely with Governor Clinton and a handful of other party leaders, Smith helped orchestrate the election of Antifederalist delegates to the New York convention, including the election of Governor Clinton in Ulster County. [96]

Accordingly, beginning in September of 1787 Melancton Smith was ideally situated as a member of Congress and chief lieutenant to Governor Clinton to assume the mantle of Brutus. It is thus no surprise that Melancton Smith became the self-styled floor manager for the Antifederalists during the New York ratification convention in June of 1788. Arguably, Smith’s electioneering efforts on behalf of Antifederalists may have been too successful. Due to the size of the supermajority of Antifederalists elected to the New York convention, ratification would become a challenge, as will be discussed in Part 5 (pending).[97]

Tillinghast’s letter to Hughes letter dated 27 January 1788

During the ratification debate New York became an epicenter of Antifederalist activity. From October 1787 through July 1788 “a never-ending stream” of political essays, letters, poems, news reports and convention debates filled New York newspapers. “Nowhere else were the people as well informed about the Constitution as in New York.”[98] The close coordination between Smith, New York Governor George Clinton, and other Antifederalist leaders is evidenced in a 27 January letter from Charles Tillinghast to Hugh Hughes.[99] Tillinghast’s letter also provides clues about the deliberative, internal procedure for publication of Antifederalist essays.

Tillinghast wrote to Hughes providing an update about the placement of Hughes’ pseudonymous essays Expositor and Interrogator in Thomas Greenleaf’s newspaper. Among other things, Tillinghast indicated that he consulted with “the General” (John Lamb) about Hughes’ essays. Tillinghast also shared that “I put the Interrogator into the hands of Cato, who gave it to Brutus to read, and between them, I have not been able to get it published, Cato having promised me from time to time that he would send it to Greenleaf.”[100]

The fact that Cato gave the essay to Brutus is evidence of collaboration between Clinton and Melancton Smith. In January of 1788 both Clinton and Smith were in Poughkeepsie as the New York Assembly was meeting beginning on 9 January 1788. According to Tillinghast’s letter, Cato promised that he would “send” the piece to Thomas Greenleaf (who was located in New York City). The statement that Cato “gave” the essay to Brutus is consistent with Clinton and Smith being in close physical proximity in January (in Poughkeepsie), away from Greenleaf in New York City.[101] When the New York Assembly wasn’t meeting in Poughkeepsie, Smith lived in New York City where he had convenient access to Greenleaf, unlike other New York Antifederalists living in upstate New York or Albany, like Robert Yates. Given the fact that Smith was a close political confidant of Governor Clinton, it should not be surprising that they were collaborating regarding the publication of Antifederalist essays, as evidenced by Tillinghast’s letter.

This post continues in Part 3 will continue with a discussion of additional attribution evidence, including alignment between Melancton Smith’s speeches at the New York ratification convention and Brutus. Part 4 will discuss newly uncovered speeches by Melancton Smith which further confirm Melancton Smith’s identity as Brutus.

Endnotes

[1] Perhaps the mashup “Brulancton” will catch on as the portmanteau for the “Brutus – Melancton Smith Authorship Thesis.”

[2] Abraham Yates was a leading Antifederalist, a member of Congress, and the uncle of Robert Yates, one of Alexander Hamilton’s co-delegates to the Constitutional Convention. Unlike Hamilton, who had supported and signed the Constitution, Robert Yates believed that the Constitutional Convention had exceeded its authority by attempting to replace, rather than amend the Articles of Confederation. Robert Yates departed the Convention in July of 1787 with the third New York delegate, John Lansing, Jr.

[3] DHRC, 20:638.

[4] In the January 23rd letter, Smith asked: “What are the cases in equity arising under the Constitution?” “What are the cases of equity under Treaties?” One week later Brutus 11 similarly asked:

What latitude of construction this clause should receive, it is not easy to say…This article, therefore, vests the judicial with a power to resolve all questions that may arise on any case on the construction of the constitution, either in law or in equity.

In the January 23 letter Smith inquired: “Will not the supreme court under this clause have a right to enlarge the extent of the powers of the general government and to curtail that of the States at pleasure?—” Brutus 11 responded that: “Every adjudication of the supreme court, on any question that may arise upon the nature and extent of the general government, will affect the limits of the state jurisdiction. In proportion as the former enlarge the exercise of their powers, will that of the latter be restricted.”

In addition to questioning the federal courts’ “equitable” powers, Brutus 11 cites to the works of Grotius about courts of equity. Brutus 12 and 14 also critique the equitable powers of the federal courts. This very subject is addressed in Smith’s convention speech on July 5th.

[5] It makes sense that Smith would reach out to Abraham Yates and Samuel Jones for their legal expertise. Yates chaired the committee that drafted the New York constitution in 1777. In January of 1788 Jones and Richard Varick were in the process of codifying the laws of New York, which was published in 1789. DHRC, 19:103.

[6] All of the Brutus letters first appeared in Thomas Greenleaf’s New York Journal. DHRC, 19:103.

[7] Both Smith’s January 23 letter and Brutus 11 use the identical phrase that the judicial power would operate in a “silent and imperceptible manner” to enlarge the power of the general government. Brutus 15 similarly argued that the courts would extend the limits of the general government “gradually, and by insensible degrees.” In 1784, Melancton Smith’s used the phrase “gently and imperceptibly” in a pamphlet criticizing the ruling in the case of Rutgers v. Waddington (discussed below).

[8] Smith’s January 23 letter indicated that “very little has yet been written” about “judicial powers” under the proposed Constitution. Brutus 11 replicates this observation, explaining that “[m]uch has been said and written upon the subject of this new system on both sides, but I have not met with any writer, who has discussed the judicial powers with any degree of accuracy.” DHRC, 20:680.

[9] The largest collection of Melancton Smith papers is held by the New York State Library in Albany, but it only consists of two boxes of manuscripts. Unlike other members of the founding generation who are chronicled in well researched biographies, Smith does not have a published biography. Fortunately, Robin Brooks’s PhD dissertation provides an excellent entry point into Smith’s largely untold story. Robin Brooks, Melancton Smith: New York Anti-Federalist 1744-1798 (1962)(hereinafter “Brooks dissertation”).

[10] As described by William Treanor, Smith’s 1784 pamphlet assailing the result in Rutgers was “the revolutionary era’s most significant critique of judicial review.” Richard M. Treanor, “The Genius of Hamilton and the Birth of the Modern Theory of the Judiciary,” in The Cambridge Companion to the Federalist, Jack N. Rakove & Colleen A. Sheenan, eds. (Cambridge University Press, 2020), 465.

[11] Earlier generations of historians and contemporaneous sources speculated that Brutus was Abraham Yates, Jr., Governor George Clinton, Richard Henry Lee, John Jay, or Thomas Treadwell. DHRC, 19:103.

[12] By way of example, Antifederalist leaders organized as the “New York Federal Republican Committee” reprinted and circulated pseudonymous essays to their allies. DHRC, 20:894. In fact, Melancton Smith played a leading role organizing New York Antifederalists and setting up the Federal Republican Society. Joseph Kent McGaughy, “The Authorship of The Letters from the Federal Farmer, Revisited,” New York History (April 1989), 153-170, 162. It is also noteworthy that there was substantial overlap between Antifederalist authors who routinely borrowed their best arguments from each other. In particular, the early essays of Brutus and the Federal Farmer reflect collaboration between allies. Herbert J. Storing, The Complete Anti-Federalist (University of Chicago Press, 1981), 2:446, n. 2.

[13] Joel A. Johnson, “Brutus and Cato Unmasked: General John Williams’s Role in the New York Ratification Debate, 1787-88,” The Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society (October 2008), 292-337. Another example of the danger of relying on subsequently delivered speeches to prove attribution is Robert H. Webking’s suggestion that Melancton Smith was the Federal Farmer. Webking’s thesis is problematic as it is derived from the similarities between the arguments of the Federal Farmer and the arguments made by Smith at the New York convention, more than half a year later. Robert H. Webking, “Melancton Smith and the Letters from the Federal Farmer,” The William and Mary Quarterly, vol. 44, no. 3, (July 1987), 510-528. To his credit, Webking acknowledges that his Melancton Smith – Federal Farmer attribution is at best “well informed speculation.” Webking, 511.

[14] For purposes of simplicity, attribution evidence prior to the publication of the Brutus essays will be referred to as “pre-authorship” evidence. By contrast, “post-authorship” evidence is properly viewed with skepticism as the lifting of passages from pseudonymous essays by a convention delegate only demonstrates affinity, not authorship.

[15] Indeed, on the same day of John Williams’ first convention speech at least one convention delegate questioned his “composition.” In a letter to John Lamb, Charles Tillinghast reported that Morgan Lewis questioned whether Williams had “penned” his June 21 opening speech. Another observer, Greswold, commented that Williams “compiled it from New York papers.” Admittedly, Tillinghast was more forgiving, writing that Williams “had as much credit with me, as Mr. Hamilton had, for retailing, in Convention, Publius – this silenced the Gentlemen.” DHRC, 22:1796.

[16] The Treaty of Paris officially ended the Revolutionary War. It became the law of the land when it was ratified by Congress in January of 1783 although signed versions were not exchanged until 1784.

[17] Peter Charles Hoffer, Rutgers v. Waddington: Alexander Hamilton, the End of the War for Independence, and the Origins of Judicial Review (University Press of Kansas, 2016). James Duane’s decision in the Rutgers case is discussed beginning at 77.

[18] Federalist 78.

[19] A total of nine names are listed on the pamphlet, with Melancton Smith as the first author.

[20] A writ of error in late 18th century New York state was an appeal to the New York Court of Impeachment and Errors. The composition of the court, which requires explanation for modern audiences, consisted of the deputy-governor (who was president of the state senate), the entire state senate, the chancellor, and the three judges of the state supreme court. The hybrid court was created by the state constitution of 1777 and implemented by law in 1784.

[21] Treanor, 464.

[22] Rutgers pamphlet at 12.

[23] Rutgers pamphlet at 10.

[24] Rutgers pamphlet at 10.

[25] Rutgers pamphlet at 11.

[26] Brutus 2 and 3 also use the phrase “security of liberty” in other contexts.

[27] Rutgers pamphlet at 12.

[28] Deuteronomy, 4:34.

[29] Brutus 14 observed that “writs of error” were the “practice of the courts in England and of this state.”

[30] DHRC, 23:2275, n. 12.

[31] DHRC, 23:2202.

[32] Admittedly, many of these terms and phrases were widely used during the ratification debate, but taken together provide additional, incremental attribution evidence.

[33] The Rutgers pamphlet explains that “in a free government” people should be informed of the conduct of government officials. Pamphlet at 13. The pamphlet argues that the holding in Rutgers is “dangerous to the freedom of our government…” Pamphlet at 15.

[34] DHRC, 23:2214.

[35] Rutgers pamphlet at p. 10.

[36] Among other reasons, writers selected pseudonyms for the “classical allusions, the implication of ancient learning that was thereby conferred, or the association with the figure whose name had been appropriated.” Eric Burns, Infamous Scribblers: The Founding Fathers and the Rowdy Beginnings of American Journalism (PublicAffairs, 2006), 167.

[37] https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-04-02-0114

[38] DHRC, 19:16. Hamilton responded to A Republican on September 15. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-04-02-0135

[39] By contrast, Jefferson described his admiration of more democratic figures Bacon, Newton & Locke. Thomas Jefferson to Benjamin Rush, 16 January 1811 (recounting a conversation in 1791). https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/03-03-02-0231

[40] “A Republican,” The Resolutions of Congress, of the 18th of April 1783: Recommending the States to invest Congress with the Power to Levy An impost for the Use of the States… (New York, 1787) (Evans 20783)(hereinafter the “Republican pamphlet”).

[41] DHRC, 19:xxxvi.

[42] https://csac.history.wisc.edu/2025/04/08/americas-first-proposed-federal-tariff-the-imposts-of-1781-and-1783/

[43] The [New York] Daily Advertiser, 26 February 1787. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-04-02-0030

[44] Treanor, 465.

[45] Michael J. Klarman, The Framers’ Coup: The Making of the United States Constitution (Oxford University Press, 2016), 26-27. In 1790, when Rhode Island was the last state to ratify the Constitution, Vice President John Adams observed that,“[t]he opposition of Rhode Island to the impost seems to have been the instrument which providence thought fit to use for the great purpose of establishing the present constitution.” John Adams to Jabez Bowen, 27 February 1790. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/06-20-02-0155

[46] DHRC, 19:xxxvi.

[47] John P. Kaminski, George Clinton: Yeoman Politician of the New Republic (Madison House, 1993), 90.

[48] New York agreed with the concept that revenue from the impost could be used by Congress to pay down wartime debut for the next twenty-five years. Nevertheless, as a procedural matter New York disagreed as to the procedure to collect the impost. In addition to wanting its own officials to collect the tax, New York reserved the right to pay Congress with New York paper currency. Kaminski, George Clinton, 92; DHRC, 19:xxxviii.

[49] DHRC, 19:xxxviii.

[50] Clinton’s public position was that the New York Constitution only permitted special sessions “for extraordinary occasions.” DHRC, 19:xxxix.

[51] The Continentalist No. IV, 30 August 1781. The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, vol. 2, 1779–1781, ed. Harold C. Syrett (Columbia University Press, 1961), 669–674. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-02-02-1191

[52] Syrett, The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, 3:647–649. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-03-02-0492

[53] According to historian John Bach McMaster, Hamilton’s petition was a “clear, forcible, and concise statement of the reason why the impost should be passed, and closed with an observation as pointed as it was just.” Hamilton’s petition concluded by arguing “[t]hat Government implies trust; and every government must be trusted so far as is necessary to enable it to attain the ends for which it is instituted; without which insult and oppression from abroad confusion and convulsion at home.” John Bach McMaster, A History of the People of the United States, From the Revolution to the Civil War (D. Appleton & Co, 1900), vol 1, 367.

[54] Cite……

[55] “Remarks on an Act Granting to Congress Certain Imposts and Duties,” 15 February 1787. Syrett, The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, 4:71–92. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-04-02-0030

[56] DHRC, 19:xl.

[57] “Notes for Second Speech of 17 July 1788.” Syrett, The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, 5:173-174. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-05-02-0012-0073

[58] Historian Paul Smith estimates that the speech was delivered on 27 July 1786. Paul H. Smith, Letters of Delegates to Congress (Library of Congress, 1995), 23:416.

[59] Kaminski, George Clinton, 93.

[60] Kaminski, George Clinton, 93; DHRC, 19:xxxix.

[61] In the fourth paragraph of Brutus 1, the question is described as “monumental.”

[62] Other pseudonymous essays and speakers likewise display the same approach, which is far from unique. Yet, it is argued that this method of argument is a particular characteristic of Brutus (Smith).

[63] Repeating examples can be found in Brutus 1, 2, 4, 6, 12, 15, & Plebeian.

[64] Brutus 1, 4, 6.

[65] Brutus 12.

[66] Brutus 1, Plebeian.

[67] Examples can be found in Brutus 3 (“this is the great end always in view”), Brutus 4 (“object ever in view”); Brutus 5 (“the objects the legislature had in view”); Brutus 6 (“answer the ends”), Brutus 10 (“answer the end”), Brutus 11(“the great end and design it professedly has in view”); Brutus 12 (“the principal ends and designs it has in view”); Brutus 16 (“the principal end which should be held in view”); Plebeian (“answer the purpose”), Smith’s convention speech of 17 July 1788 (“answer the end”). See also Republican pamphlet at 62 (“the great end will be attained”).

[68] Examples can be found in Brutus 1 (“Let us now proceed to enquire”), Brutus 2 (“I shall not now enquire”),Brutus 5 (“We will next enquire”), Brutus 6 (“it is then necessary to enquire”), Brutus 8 (“Let us then enquire”), Brutus 9, Brutus 11, Brutus 12 (“Let us enquire”), Plebeian (“We ought therefore to enquire”)

[69] This bears further review…. Compare Publius (Hamilton v. Madison spellings….)

[70] Brutus 1 (“a few observations…will fully evince”); Brutus 2 (“from these observations it appears); Brutus 3 (“It has been observed”); Brutus 4 (“I would observe”) Brutus 5 (“On this I observe”); Brutus 6 (“I shall add but one other observation”); Brutus 12 (“I would here observe”), Brutus 16 (“The following things may be observed”); Plebeian (“will only observe”).

[71] Brutus 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 14, 15, Plebeian.

[72] Cecelia M. Kenyon, The Antifederalists (The Bobbs – Merrill Co., 1966), 323.

[73] Bruce Frohnen, The Anti-Federalists: Selected Writings and Speeches (Regency House, 1999), 372.

[74] William Kent, Memoirs and Letters of James Kent, LLD (Little, Brown & Co., 1898), 305.

[75] Kent, 306 (letter to Elizabeth Hamilton dated 10 December 1832).

[76] Smith, Letters of Delegates to Congress (Library of Congress, 1995), 23:416.

[77] Of course, Smith would eventually support unconditional ratification after New Hampshire and Virginia voted to ratify as the nineth and tenth states.

[78] When using the term “internal police,” Smith is referring to the broadly defined “police power,” which is the government’s inherent authority to regulate and protect the public’s health, safety and welfare. Although the Tenth Amendment doesn’t specifically mention the police power, the powers reserved to the states include the police power.

[79] Republican pamphlet at 52. Smith expressed the same concern in a letter to Gilbert Livingston discussing precedents for the newly forming federal government: “For if you once pass a Law or Resolution to grant the Senate the right, it will never be surrendered.” Melancton Smith to Gilbert Livingston, 1 January 1789, DHRC, 23:2496. See also “A Federal Republican” Nos. 1–3, New York Journal, 27 November, 11 December 1788, and 1 January 1789; DHFFE, III, 212–13, 214–15, 261–64.

[80] The right of free deliberation is mentioned in Plebeian.

[81] Republican pamphlet at 3.

[82] Republican pamphlet at 3.

[83] As the printers employed by the Constitutional Convention Dunlap and Claypoole printed broadside copies of the Constitution for the delegates. Accordingly, they had advance access to the Constitution’s text. By October 31, approximately seventy-five newspapers had printed the Constitution. DHRC, 13:200.

[84] The sixteen Brutus essays were published in eighteen installments between 18 October 1787 and 10 April 1788. DHRC, 19:103.

[85] Cecil L. Eubanks, “New York: Federalism and the Political Economy of Union,” in Ratifying the Constitution, eds. Michael Allen Gillespie & Michael Lienesch (University of Kansas Press, 1989), 310.

[86] Eubanks, 302,

[87] Gordon Wood, The Creation of the American Republic, 1776-1787 (W. W. Norton, 1972), 486. Jackson Turner Main, The Anti-federalists: Critics of the Constitution, 1781-1788 (University of North Carolina Press, 1961), 48.

[88] Wood, 487; Eubanks, 310-11.

[89] New York’s other two delegates were John Haring, and Abraham Yates, Jr.

[90] Kaminski, Reluctant Pillar, 65.

[91] Paul H. Smith, Letters of Delegates to Congress, 24:444, n. 1; Julius Goebel, Jr., “Melancton Smith’s Minutes of Debates on the New Constitution,” Columbia Law Review 64 (Jan. 1964), 26-43; and DHRC, 1:327-40, 13:229-41.

[92] Smith indicated that “I would have sent you a copy of it [the Constitution], with the objections I have to it, but I do not think it best to put you to cost of postage.” Melancton Smith to Andrew Craigie, 4 October 1787, DHRC, New York Supplement, 70.

[93] Gerry (believed to have been the Federal Farmer) likely attempted to remain in contact with his Antifederalist allies in New York. DHRC, 5:812, n. 2.

[94] Brooks dissertation, 44.

[95] Melancton Smith to Abraham Yates, Jr. dated 23 & 28 Jan 1788, DHRC, 20:638 & 671; Melancton Smith to Nathan Dane dated 28 June 1788, DHRC, 22:2015; Nathan Dane to Melancton Smith dated July 3 1788, DHRC, 21:1254.

[96] The Albany Anti-Federal Committee to Melancton Smith, 1 March 1788, DHRC, 20:834; DHRC, 21:1542; Kaminski, George Clinton, 139-141.

[97] DHRC, 37:lvii; David J. Siemers, The Antifederalists: Men of Great Faith and Forbearance (Rowman & Littlefield, 2003), 137-138.

[98] John P. Kaminski, “New York: The Reluctant Piller,” in The Reluctant Piller: New York and the Adoption of the Federal Constitution, ed, Stephen L. Schechter (Russell Sage College, 1985), 72; Michael J. Faber, The Anti-Federalist Constitution: The Development of Dissent in the Ratification Debates (University Press of Kansas, 2019), 37.

[99] Tillinghast was the son-in-law of Antifederalist leader John Lamb. DHRC, 19:8.

[100] DHRC, 20:667.

[101] The assertion that Clinton and Smith were collaborating over the publication of Antifederalist essays assumes that Tillinghast knew Cato and Brutus’s identity. Nevertheless, this deduction is reasonable as John Lamb was the chairman and Tillinghast, his son-in-law, was the secretary of the Federal Republican Committee. DHRC, 19:497, 499.