Confirmed: Antifederalist Melancton Smith was Brutus

Overview of the Brutus – Melancton Smith Authorship Thesis (Part 1)

Adam P. Levinson, Esq. & John P. Kaminski, PhD

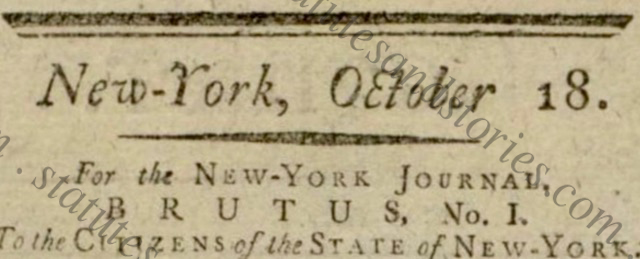

In the fall of 1787 America was ramping up for the unprecedented national debate over whether to ratify the Constitution proposed in Philadelphia. Although the much anticipated Constitution was initially celebrated, Antifederalists did not wait long to raise the alarm.[1] Much of the public debate reverberating throughout the country appeared in newspapers, broadsides, and pamphlets by anonymous authors using pseudonyms. Within a month of the Constitution’s debut, two Antifederalist publications attracted particular attention. Sixteen letters written by Brutus were printed in the New York Journal between 18 October 1787 and 10 April 1788. Eighteen letters by the Federal Farmer were published in two consecutively-numbered pamphlets in November of 1787 and May of 1788. The identity of Brutus and the Federal Farmer was unknown for many years before historians incorrectly attempted to identify them. Sufficient new evidence has now surfaced to allow conclusive attribution of both of these influential Antifederalist publications.

In mid-October of 1787, James Madison read an Antifederalist essay which quickly grabbed his attention. Writing to Virigina Governor Edmund Randolph, Madison summarized the anticipated objections appearing in the papers. Yet, after reading the first Brutus essay, Madison warned that, “[a] new Combatant however with considerable address & plausibility, strikes at the foundation.”[2] Alexander Hamilton no doubt shared similar concerns after reading Brutus’ critique, leading Hamilton to recruit John Jay and later James Madison to write The Federalist.[3] A year later, New York Antifederalist Melancton Smith would describe the ratification process as “one of the most astonishing events in the history of humane affairs.”[4]

The eighty-five Federalist essays have long been studied and praised by historians, resulting in the “thickest overlay of scholarly interpretation ever lavished on a set of essays.”[5] Yet, the sixteen Brutus essays were not reprinted in their entirety until 1971.[6] Nevertheless, scholars concede that Publius was not writing in a vacuum as an academic exercise. Rather, the famous Federalist essays are properly understood as an iterative back-and-forth dialogue with Antifederalist opponents.[7] In particular, modern historians now recognize that Brutus stands out as the “chief interlocutor”[8] and “most formidable antagonist of the immortal Publius.”[9] Indeed, Madison’s first and arguably most famous essay, Federalist 10, was likely written to refute Brutus I.[10]

Although the Federalist essays don’t refer to Brutus by name, Hamilton felt the need to provide a “point-by-point rejoinder” to Brutus’ assault on judicial supremacy.[11] In turn, Brutus provided the “most effective direct response to Publius.”[12] In addition to responding to Publius, Brutus also took aim at other Federalists. For example, Brutus “effectively demolished” Pennsylvania delegate and future Supreme Court justice James Wilson’s defense of the omission of a bill of rights.[13]

This blog post is the first of a multi-part series exploring the authorship of the sixteen letters of Brutus. The Brutus – Melancton Smith Authorship Thesis argues that Brutus was Melancton Smith, Alexander Hamilton’s chief opponent at the New York ratification convention in Poughkeepsie. Part 1 begins with an overview of existing scholarship. Part 1 then offers a summary of the detailed new evidence which has been compiled by Statutesandstories.com in collaboration with John P. Kaminski. Part 2 will provide an exhaustive review of the evidence summarized in Part 1. Part 3 will discuss newly uncovered speeches by Melancton Smith.

As pointed out by historian Gordon Wood over fifty years ago, the attribution of pseudonymous essays is “a difficult business.” In 1974, Wood challenged the longstanding view that Richard Henry Lee was the Federal Farmer, one of Brutus’ closest Antifederalist allies. In so doing, Wood fully recognized that the process of attributing authorship is “a business of great responsibility,” as accepted attributions tend to get bound in the literature and taken for granted over time. Wood concluded that, “[b]arring some unforeseen manuscript discovery, the authorship of the Letters from the Federal Farmer will probably never be definitively known.”

Yet with the completion of the seminal forty-seven volumes of the Documentary History of the Ratification of the Constitution (“DHRC”), scholars today have unrivaled access to sources unavailable to prior generations of historians. Moreover, working in collaboration with John P. Kaminski, Statutesandstories.com has compiled additional and mounting evidence of the identity of both the Federal Farmer and Brutus.

In 1988 Kaminski presented a paper convincingly arguing that Elbridge Gerry was the Federal Farmer. Nonetheless, many historians continue to attribute the letters of the Federal Farmer to Melancton Smith or Richard Henry Lee. In a series of blog posts earlier this year, Statutesandstories argued that it is past time to conclude that Elbridge Gerry was in fact the Federal Farmer. Click here for a link to the Federal Farmer – Elbridge Gerry Authorship Thesis (“FEAT”) a multi-part series which presents new evidence in support of Kaminski’s attribution of Elbridge Gerry as the Federal Farmer. With the identity of the Federal Farmer confirmed as Elbridge Gerry, the stage is set for Melancton Smith to claim his rightful role as Brutus.

Brutus authorship attributions

During the ratification campaign, contemporaneous sources speculated that Brutus was Abrham Yates, Jr., Governor George Clinton, Richard Henry Lee, or John Jay.[14] Over the years, scholars have offered at least four other possibilities. Beginning in the late 19th century, historians Samuel B. Harding and Paul Leicester Ford proposed that Thomas Treadwell was Brutus, as Tredwell used the pseudonym in 1789.[15] Four years later Ford later reconsidered in favor of Robert Yates, but did not specify his reasons.[16] As a delegate to the Constitutional Convention and a skilled lawyer, the Yates attribution was certainly understandable.

In his 1961 classic work, The Anti-federalists, historian Jackson Turner Main continued to rely on Ford’s attribution that Robert Yates was Brutus.[17] When Morton Borden compiled the Anti-Federalist Papers in 1965, he expressed doubts that Yates could have been Brutus.[18] Yet, Bordon did not suggest another replacement attribution. The following year, Cecelia Kenyon abided by the widely accepted Robert Yates attribution. Kenyon opined that “the Antifederalists had no publicist more able than Robert Yates,” the author of Brutus.[19]

When William Jeffrey, Jr., republished all sixteen Brutus essays in 1971, he acknowledged that the letters were commonly attributed to Robert Yates. Conceding that unless or until hard evidence was uncovered, “we shall never know, with any certainty,” Brutus’ identity. With that caveat, Jeffrey offered his own candidate, Melancton Smith. Jeffrey reasoned that Smith was a leader of the Antifederalists at the New York ratification convention. Importantly, Jeffrey drew connections between A Plebeian drafted by Smith and Brutus.[20]

By 1976, Ann Diamond summarized that Robert Yates was “generally thought to be Brutus,” but other candidates included Treadwell and Smith. Recognizing that there was “no decisive evidence to settle the question of authorship,” Diamond supported the Yates attribution. Diamond argued that Brutus’ “remarkably prophetic attack on the power of the proposed federal judiciary could only be the work of a judge,” which pointed to Yates.[21]

In 1981, in his seven-volume series The Complete Anti-Federalist, Herbert Storing acknowledged that he was unable to unearth any additional evidence to support or refute the longstanding Robert Yates attribution. Recognizing Brutus’ considerable legal knowledge, Storing discounted Jeffrey’s attribution of Melancton Smith. According to Storing, the circumstantial case for Smith was “not a very persuasive one.”[22] By 1987, Murray Dry noted that Brutus was “surely more open to the proposed Constitution than was Yates,” who departed the Constitutional Convention. Dry admitted, unfortunately, that the identification of Brutus “remains uncertain even today.”[23]

By 1990, informed opinion began to include Melancton Smith as a serious contender alongside Yates. Nevertheless, when Gaspare J. Saladino reviewed the pseudonyms used during ratification, he acknowledged that the authorship of Brutus “has not been determined.”[24] In 1993, Bernard Bailyn agreed that the author of the Brutus essays “is not known,” suggesting that Brutus was Robert Yates or Abraham Yates, Jr.[25]

Yet, without mentioning Smith, in 1999 Bruce Frohnen indicated that Brutus’ “powerful and highly influential essays are generally ascribed to Robert Yates.”[26] Frohnen did not consider Smith as the author of Brutus because Frohnen incorrectly understood that the letters of the Federal Farmer “are now generally thought to have been written by Melancton Smith.”[27] In 2003, Terrence Ball published an expanded edition of “The Federalist with the letters of Brutus.” Ball’s “best guess” as to the identity of the “redoubtable polemicist who call himself Brutus” was Robert Yates.[28]

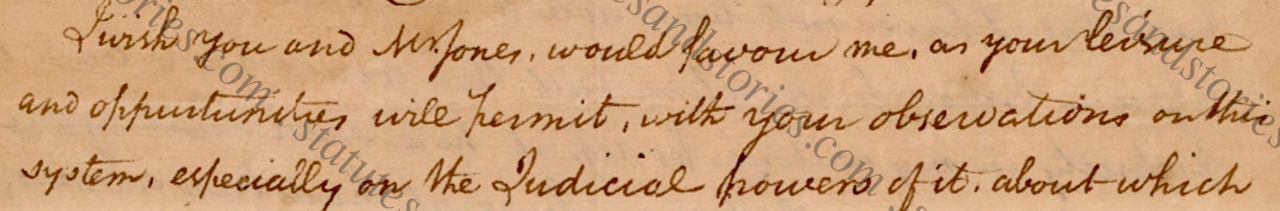

The first New York volume of the Documentary History of the Ratification of the Constitution (“DHRC”) was also published in 2003. After summarizing the competing authorship attributions, the DHRC added that a letter dated 23 January 1788 from Melancton Smith to Abraham Yates, Jr., “lends credence to the belief that Smith was Brutus.” As described by the DHRC, in his letter “Smith requested that both Yates and Samuel Jones, another Antifederalist leader, provide him with their ‘observations’ on the Constitution, ‘especially on the Judicial powers of it.’ Smith believed that the judicial powers ‘clinch’ all the other powers of the Constitution.”[29] As will be explained in greater detail in Part 2, this 23 January 1788 letter is powerful attribution evidence. In particular, the January letter connects Smith to the Brutus essays as they were being written.

Thereafter, David J. Siemers observed that Brutus’ identity was uncertain, “but speculation has centered on Melancton Smith.”[30] In 2008 Joel A. Johnson proposed an entirely new attribution, New York convention delegate John Williams. The suggestion that Williams was Brutus rests almost entirely on the fact that Williams cited at length from Brutus essays during the New York ratification convention.[31] As will be discussed in Part 2, this attribution is fundamentally flawed as Williams also cited from Cato and other Antifederalist sources without attribution.

Notwithstanding the DHRC’s monumental work, historians and political scientists continue to discount Smith’s role as Brutus.[32] In other cases, Smith is credited as the Federal Farmer rather than Gerry.[33] In 2009 Michael P. Zuckert and Derek A. Webb entertained the possibility that Smith was the author of either Brutus or the Federal Farmer. As an alternative, Zuckert and Webb offered the possibility of authorship by the “Melancton Smith circle” of “like-minded individuals.”[34] In 2020 Richard M. Treanor focused on Brutus’ concern with judicial review to support the attribution that Smith was Brutus.[35] Not surprisingly, the internet is teeming with incorrect attributions, including websites of reputable institutions.[36] When asked the question, “who was the Antifederalist Brutus who wrote essays in 1787-1788?,” ChatGPT currently identifies Robert Yates.[37] As recognized by Gordon Wood, inertia is a powerful force when it comes to pseudonymous writings.

Summary of attribution evidence

It has been over fifty years since William Jeffrey first suggested that Melancton Smith was Brutus. The DHRC has supported Jeffrey’s thesis since 2003. Building on this attribution, Statutesandstories has uncovered additional evidence which helps confirm the conclusion that Melancton Smith was in fact Brutus. Newly assembled evidence falls into the following categories outlined below. While no single category of evidence is alone conclusive, it is believed that the combined weight of the mutually reinforcing evidence is determinative. The totality of the following attribution evidence is hereinafter referred to as the Brutus – Melancton Smith Authorship Thesis[38]:

- Tillinghast’s letter to Hughes: Antifederalist Charles Tillinghast wrote to Antifederalist Hugh Hughes on 27 January 1788 about the placement of the pseudonymous essay Expositor in Thomas Greenleaf’s newspaper. Tillinghast also shared that “I put the Interrogator into the hands of Cato, who gave it to Brutus to read, and between them, I have not been able to get it published, Cato having promised me from time to time that he would send it to Greenleaf.”[39] The fact that Cato gave the essay to Brutus, is evidence that Clinton gave the essay to Melancton Smith. In January of 1788 both Clinton and his political lieutenant Smith were in Poughkeepsie as the New York Assembly was meeting beginning on 9 January 1788. According to Tillinghast’s letter, Cato promised that he would “send” the piece to Thomas Greenleaf (who was located in New York City). Another clue is the statement that Cato “gave” the essay to Brutus, which is consistent with Clinton and Smith being in close physical proximity in January (in Poughkeepsie), away from Greenleaf in New York City. When the New York Assembly wasn’t meeting in Poughkeepsie, Smith lived in New York City where he had convenient access to Greenleaf, unlike other New York Antifederalists living in upstate New York or Albany, like Robert Yates.

- Smith’s opposition to Rutgers case: In 1784, Melancton Smith was the lead author of “an address, &c. to the people of the State of New-York” (hereinafter Smith’s “Address”) criticizing the outcome of the controversial case of Rutgers v. Waddington.[40] Smith’s 1784 Address aligns with Brutus’ concerns over judicial supremacy, beginning with Brutus 11. Moreover, on 5 July 1788 Smith made a motion at the New York ratification convention regarding writs of error[41] (appeals to the New York Court of Errors/Senate), which was the identical procedure invoked by Smith’s Rutgers Address in 1784. The fact that Smith took an active role in seeking to reverse the Rutgers decision may also help explain his subsequent use of the Brutus Alexander Hamilton was the prevailing attorney in the Rutgers case.

- Use of the pseudonym Brutus: Multiple explanations directly connect Smith to the Brutus pseudonym, apart from the ostensible reason that Marcus Junius Brutus attempted to defend the Roman republic from Julius Caesar on the Ides of March, 44 B.C.E. First, Governor Clinton wrote under the pseudonym Cato. Alexander Hamilton is believed by many to have replied to Clinton’s Cato essay, writing as Caesar. Smith was a loyal political lieutenant of Governor Clinton. This explanation makes sense as Cato appeared on 27 September and Caesar’s attack on Cato followed on 1 October. This timing would have allowed Smith approximately two weeks to select the pseudonym, when he published his first Brutus essay on 18 October. Second, in July of 1787 Hamilton wrote a letter to the New York Daily Advertiser highly critical of Governor Clinton for improperly attempting to undermine the Constitutional Convention before it had completed its work. Third, Alexander Hamilton was a great admirer of Julius Caesar. According to Thomas Jefferson, Hamilton claimed that Julius Caesar was the “greatest man who ever lived.”[42] Fourth, Smith was at odds with Hamilton over the Rutgers case dating back to 1784. Thus, Smith had several overlapping reasons to assume the name Brutusto defend Clinton and challenge Hamilton.

- Stylistic fingerprints: As will be set forth at great length in Part 2, stylistic and linguistic fingerprints align Smith and Brutus. Importantly, many of Smith’s stylistic fingerprints can be identified in his correspondence prior to his authorship of the Brutus essays, as well as his subsequent speeches in the New York convention. For example, Smith’s 23 January letter to Abraham Yates uses the following phrases: judicial powers will clinch all other powers and extend them in a “silent and imperceptible manner.” Brutus 11 uses the identical phrase that judicial power will operate in a “silent and imperceptible manner.” Similarly, Smith’s 23 January letter objected that the federal courts would have powers that were “totally independent, uncontroulable and not amenable to any other power.” This directly aligns with the concern in Brutus 11 that the courts would be rendered “totally independent” and Brutus 12 that the courts would be vested with supreme and uncontroulable power.” This phraseology and concern appears in Smith’s convention speeches on June 21 and July 1.

The first sentence of Smith’s Rutgers Address from 1784 discusses the rights and “the happiness of people who live in a free government.” The same concepts and terms are repeatedly used by Brutus and in Smith’s convention speeches. For example, the first sentence in Brutus 4 declares that there can be no “free government” when the people lack the power to make the laws under which they are governed. The “happiness of the people” is discussed in the second paragraph. Likewise, the first sentence of Brutus 9 declares that the goal of government is to “protect the rights and promote the happiness of the people.” Brutus 9 also discusses concepts of “free government.” Colorful examples of fingerprints which connect Brutus to Smith’s ratification speeches include Brutus 3’s description of the Constitution as “radically defective,” which is the identical phrase used by A Plebeian and Smith’s July 23 speech. Brutus 3, 4 and 10 complain about a “shadow of representation” and representation which would be a “mere shadow” without substance. This aligns with Smith’s June 21 speech objecting to “the mere shadow of representation.” Brutus 3, 4, 14 and 16 repeatedly use the phrase “the middling class.” The same phrase is used in A Plebeian and in Smith’s speeches on June 21 and 23. Brutus 10 and Smith’s June 25 speech use the expression “heaven only knows.” This aligns with Smith’s consistent use of religious and biblical references.

- Abundant biblical citations: For decades historians have described Smith as “an ardent Presbyterian,”[43] a “pillar” of his church,[44] and “a strict churchman,”[45] who manifested a “life-long interest” in religion.[46] A close examination of the Brutus and Plebeian essays reveal dozens of biblical references and allusions. This aligns with Smith’s convention speeches and correspondence. Part 3 will provide detailed examples dating back to letters written by Smith in 1771. This is in stark contrast with the letters of the Federal Farmer(Elbridge Gerry) which contains only a single passing reference to “the days of Adam.” This aligns with David E. Narrett’s observation that the “Federal Farmer’s prose style is more ornate and more replete with classical allusions than is Smith’s.” “The more plainspoken Smith quoted from the Bible, a practice fairly common in Brutus but not in the Federal Farmer.”[47] This is consistent with efforts by scholars to categorize Antifederalist schools of thought. For example, Brutus has been described as a “middling” Antifederalist, in contrast to the Federal Farmer who falls into the “elite” strand of Antifederalist thinking.[48] This matches similar classifications of Brutus (Smith) as a “Power Anti-Federalist” and the Federal Farmer (Gerry) as a “Rights Anti-Federalist.”[49]

- Lack of inside information regarding the Constitutional Convention: Unlike Elbridge Gerry, Robert Yates and John Lansing, Smith lacked direct insider knowledge of the deliberations of the Constitutional Convention. It is thus no surprise that Brutus does not exhibit confidential or insider information from Philadelphia. By contrast, the Federal Farmer (Elbridge Gerry) repeatedly reflects such knowledge. Similarly, the Federal Farmer refers to the framers of the Constitution in the first person whereas Brutus uses the third person.

- Intimate knowledge of the Confederation Congress: Both Brutus and the Federal Farmer evidence intimate knowledge of the workings of the Confederation Congress. This makes sense as both Smith and Gerry served in Congress. An interesting distinction is that the Federal Farmer’s knowledge dates back to the drafting of the Articles of Confederation, while Brutus’ information is more recent. This is perfectly consistent with Smith’s service beginning in 1785 when he was first elected. By contrast, Gerry’s congressional service began in 1776 and explains the Federal Farmer’s first-person description of the formation of the confederation, when Gerry became a signatory to the Declaration of Independence and Articles of Confederation.

- Logical and syllogistic reasoning: Historians have repeatedly noted the “logical development”[50] of Brutus’ letters, which were among the “most powerful and well-reasoned Antifederalist writing.”[51] This aligns with the descriptions of Smith’s speeches as “acute and logical”[52] and “dry, plain and syllogistic.”[53] As will be detailed in Part 4, Brutus frequently cited maxims and axioms, which perfectly aligns with Smith’s speeches. By contrast, Smith privately opined that Chancellor Livingston was a “wretched reasoner” during the New York ratification convention.[54]

- Opposition to slavery: The evidence is overwhelming that both Smith and Brutus were ardent opponents of slavery. Brutus 3 was highly critical of the “inhuman traffic of importing slaves” in defiance of “every idea of benevolence, justice and religion.” Brutus called out “unfeeling, unprincipled, barbarous, and avaricious wretches” who would tear slaves from their “country, friends and tender connections.” This aligns with Smith’s June 20 speech critical of “those people who were so wicked as to keep slaves” and the position of southern states which was “utterly repugnant to his feelings.” Consistent with his rhetoric, Smith did not own slaves, unlike the Yateses, Lansings and John Williams who have been offered as possible Brutus Indeed, Smith has been described as “very likely the most actively anti-slavery man in the entire Congress.”[55] Smith was a founder of the New York Manumission Society and for many years was a leading member, vice-president, and chairman.

- Logistical considerations: Financial records indicate that Smith was paid for his congressional service through 5 November 1787, even though Congress failed to obtain a quorum in late October and early November. As a result, Smith had free time to confer with Antifederalist colleagues in New York City, including Richard Henry Lee and Elbridge Gerry. Smith’s own notes of Congressional proceedings in September indicate, not surprisingly, that he was an early Antifederalist. For example, Smith seconded Richard Henry Lee’s motion on September 27 to acknowledge the limitations on the power of Congress to amend the Articles of Confederation. Moreover, similarities in the early Brutus and Federal Farmer essays are consistent with Smith and Gerry collaborating in New York City with Richard Henry Lee, before Gerry returned home to Massachusetts and Lee returned to Virginia.

Needless to say, the updated Brutus – Melancton Smith Authorship Thesis builds on the scholarship of Jeffrey and the DHRC. Their work points to Smith’s authorship of Plebeian, the connection between Brutus and Plebeian, and Smith’s letter to Abraham Yates, Jr., dated 23 January 1788. All of this evidence will be discussed in the Brutus – Melancton Smith Authorship Thesis – Part 2, along with the new evidence summarized above.

Endnotes

[1] Early Antifederalist essays include Centinel, Cato and An Old Whig.

[2] Madison to Randolph, 21 Oct 1787:

[3] A memorandum by Madison entitled “The Federalist,” quoted in J. C. Hamilton, ed., The Federalist: a Commentary on the Constitution of the United States. A Collection of Essays by Alexander Hamilton, Jay, and Madison. Also, The Continentalist and Other Papers by Hamilton (Philadelphia, 1865), I, lxxxv.

[4] A transcript of the newly uncovered speech is forthcoming in the Documentary History of the Ratification of the Constitution (“DHRC”).

[5] Lance Banning, The Sacred Fire of Liberty: James Madison and the Founding of the Federal Republic (Cornell University Press, 1995), 200.

[6] Herbert J. Storing, The Complete Anti-Federalist (University of Chicago Press, 1981), 2:358.

[7] Murray Dry, “Anti-Federalism in The Federalist: A Founding Dialogue on the Constitution, Republican Government, and Federalism,” in Saving the Revolution: The Federalist Papers and The American Founding, Charles R. Kesler, ed. (The Free Press, 1987), 41 (indicating that Publius engages in “a virtual dialogue” with Brutus and the Federal Farmer); Todd Estes, “The Voices of Publius and the Strategies of Persuasion in The Federalist,” Journal of the Early Republic, 28 (Winter 2008).

[8] Emery G. Lee, III, “Representation, Virtue and Political Jealousy in the Brutus-Publius Dialogue,” The Journal of Politics, vol. 59, no. 4, 1073-95, 1075 (November, 1997).

[9] William Jeffrey, Jr. “The Letters of ‘Brutus’ – A Neglected Element in the Ratification Campaign of 1787-1788,” University of Cincinnati Law Review, vol. 40, no. 4., 643-663, 643 (1971).

[10] Lee, 1075.

[11] Shlomo Slonim, “Federalist No. 78 and Brutus’ Neglected Thesis on Judicial Supremacy,” Constitutional Commentary, vol 23, 7 (2006). Slonim argues that Federalist 78 “cannot be properly understood except in the context of Brutus’ charge that the Constitution provided, not only for judicial review, but for judicial supremacy.” Slonim, 9. Jack Rakove and Herbert Storing concur that Brutus provides the best discussion of the judiciary in the Antifederalist literature. Storing, 2:358. Rakove, Original Meanings, 397, n. 58.

[12] Michael J. Faber, The Anti-Federalist Constitution: The Development of Dissent in the Ratification Debates (University Press of Kansas, 2019), 37.

[13] Michael I. Meyerson, Liberty’s Blueprint: How Madison and Hamilton Wrote the Federalist Papers, Defined the Constitution, and Made Democracy Safe for the World (Basic Books, 2008), 100. Meyerson agrees that Brutus was Madison’s primary target in Federalist 10. Meyerson, 171.

[14] DHRC, 19:103.

[15] Samuel B. Hardin, The Contest Over the Ratification of the Federal Constitution in the State of Massachusetts(1896), 18n.

[16] Paul Leicester Ford, Pamphlets on the Constitution of the United States, Published During Its Discussion by the People, 1787-1788 (1888); DHRC, 19:103.

[17] Jackson Turner Main, The Anti-federalists: Critics of the Constitution, 1781-1788 (W.W. Norton, 1974 edition), 287.

[18] Morton Borden, The Antifederalist Papers (Michigan State University, 1965), 42. Bordon reasoned that Yates was known to have written under the pseudonym Sydney, which appeared “inferior in quality and style to the Brutusessays.” Borden’s reasoning was sound, but he was right for the wrong reasons. Sydney was written by Abraham Yates, Jr., Robert Yates’ uncle.

[19] Cecelia M. Kenyon, The Antifederalists (The Bobbs – Merrill Co., 1966).

[20] Jeffrey, 645-646.

[21] Ann Diamond, “The Anti-Federalist Brutus”, The Political Science Reviewer (Fall 1976).

[22] Storing, 2:363, n. 8.

[23] Dry, 42.

[24] Gaspare J. Saladino, “Pseudonyms Used in the Newspaper Debate over the Ratification of the Constitution in the State of New York, September 1787 – July 1788,” in New York and the Union, Stephen L. Schechter & Richard B. Bernstein, ed. (New York State Commission on the Bicentennial, 1990), 302.

[25] Bernard Bailyn, The Debate on the Constitution (Library of America, 1993), I, 1149.

[26] Bruce Frohnen, The Anti-Federalists: Selected Writings and Speeches (Regency House, 1999), 372.

[27] Frohnen, 141.

[28] Terence Ball, The Federalist with Letters of Brutus (Cambridge University Press, 2003), 436.

[29] DHRC, 19:103.

[30] David J. Siemers, The Antifederalists: Men of Great Faith and Forbearance (Rowman & Littlefield, 2003), 121.

[31] Joel A. Johnson, “Brutus and Cato Unmasked: General John Williams’s Role in the New York Ratification Debate, 1787-88,” The Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society (October 2008), 292-337.

[32] By 2018, Robert J. Allison and Bernard Bailyn reverted to the commonly held Robert Yates attribution indicating that Abraham Yates may have been Cato and his nephew Robert Yates “may have been Brutus.” Robert J. Allison and Bernard Bailyn, The Essential Debate on the Constitution: Federalist and Antifederalist Speeches and Writings (The Library of America, 2018), 1.

[33] In 1987, Robert Webking proposed that Melancton Smith was the Federal Farmer. Yet, Webking’s “well-informed speculation” relies entirely on similarities between Melancton Smith’s convention speeches and the “general thrust, specific points and reasoning” of the Federal Farmer. Robert H. Webking, “Melancton Smith and the Letters from the Federal Farmer,” The William and Mary Quarterly , vol. 44, no. 3, (July 1987), 510-528, 511. In her exhaustive narrative of the ratification process in each of the states, Pauline Maier agreed that A Plebeian was probably Melancton Smith, “who may also may have written the letters of the Federal Farmer and, in the opinion of at least one modern scholar, the newspaper essays signed Brutus.” Pauline Maier, Ratification: The People Debate the Constitution, 1787-1788 (Simon & Schuster, 2010), 338-339.

[34] Michael P. Zuckert & Derek A. Webb, The Anti-Federalist Writings of the Melancton Smith Circle (Liberty Fund, 2009), xiii. Confounding, rather than clarifying the investigation, Zuckert and Webb invited a computer-based statistical analysis by Professor John Burrows which found that “Smith came up consistently as the most likely author of both the Federal Farmer and Brutus.” Based on literary and impressionistic evidence, Zuckert and Webb are skeptical that the same individual wrote both essays. Id. at xxviii.

[35] Richard M. Treanor, “The Genius of Hamilton and the Birth of the Modern Theory of the Judiciary,” in The Cambridge Companion to the Federalist, Jack N. Rakove & Colleen A. Sheenan, eds. (Cambridge University Press, 2020), 511.

[36] Examples include The National Constitution Center (https://constitutioncenter.org/the-constitution/historic-document-library/detail/brutus-essay-no-1) (last visited on 9/29/2025) and TeachingAmericanHistory.org (https://teachingamericanhistory.org/resource/fafd-home/fafd-selected-antifederalist-collections/fafd-brutus-letters-from-the-federalist-antifederalist-debates/) (lasted visited 9/29/2025).

[37] According to ChatGPT, “The Anti-Federalist writer “Brutus” was the pseudonym used by an unknown author (or possibly authors) who wrote a series of influential essays opposing the ratification of the U.S. Constitution between 1787 and 1788. The real identity of Brutus is not definitively known, but most scholars believe that Robert Yates, a judge and delegate to the Constitutional Convention from New York, was the author.” (last searched 9/29/2025).

[38] Perhaps the mashup “Brulancton” will catch on as the portmanteau for the Brutus – Melancton Smith Authorship Thesis.

[39] DHRC, 22:667.

[40] Smith’s A Plebeian essay was similarly titled “An Address to the People of the State of New-York.” DHRC, 17:146. The Brutus essays are similarly addressed “to the People of the State of New-York” or “to the Citizens of the State of New-York.”

[41] A writ of error in late 18th century New York state was an appeal to the New York Court of Errors. As will be discussed in Part 2, the New York Court of Impeachment and Error was created by the state constitution of 1777 and implemented by law in 1784. The court consisted of the deputy-governor (who was president of the state senate), the entire state senate, the chancellor, and the three judges of the state supreme court.

[42] Thomas Jefferson to Benjamin Rush, 16 January 1811 (recounting a conversation in 1791).

[43] Broadus Mitchell & Louise Person Mitchell, A Biography of the Constitution of the United States: Its Origin, Formation, Adoption, Interpretation, 2nd ed. (Oxford University Press, 1975), 38.

[44] Robin Brooks, Melancton Smith: New York Anti-Federalist 1744-1798 (1962)(PhD dissertation), 7.

[45] James Smith, History of Duchess County, New York, with Illustrations and Biographical Sketches of Some of its Prominent Men and Pioneers (D. Mason & Co., 1882), 320.

[46] Julian P. Boyd, “Smith, Melancton,” in Dictionary of American Biography, Dumas Malone, ed. (C. Scribner’s Sons, 1943), vol. 17, 319.

[47] David E. Narrett, “A Zeal for Liberty: The Antifederalist Case Against the Constitution in New York,” New York History (July 1988), 285-317, 291.

[48] Saul Cornell, The Other Founders: Anti-Federalist and the Dissenting Tradition in America, 1788-1828 (University of North Carolina Press, 1999), 12; Siemers, 18, 121, 193. For Cornell the identity of Brutus remained “a mystery” in 1999. Cornell, 96 n. 23.

[49] Faber, 31-37.

[50] Kenyon, 323.

[51] Frohnen, 372.

[52] William Kent, Memoirs and Letters of James Kent, LLD (Little, Brown & Co., 1898), 305.

[53] Kent, 306 (letter to Elizabeth Hamilton dated 10 December 1832).

[54] DHRC, 22:2015 (Melancton Smith to Nathan Dane, dated 28 June 1788).

[55] Brooks, 282.