Melancton Smith’s Syllogistical Reasoning Style

The “Brutus – Melancton Smith Authorship Thesis” (Part 4)

Adam P. Levinson, Esq. & John P. Kaminski, PhD

During his first convention speech as the floor leader of the New York Antifederalists, Melancton Smith identified several preliminary considerations which he hoped would govern the delegates during the New York ratification convention.[1]Smith agreed that “the discussion of the important question now before them” ought to be entered upon with open minds and “with a determination to form opinions only on the merits of the question, from those evidences which should appear in the course of the investigation.” Each of these sentiments had been expressed months earlier – repeatedly – by Brutus.

Brutus 1 began the first of his sixteen essays[2] by describing the debate over the ratification of the Constitution as “[t]he most important question that was ever proposed to your decision.”[3] Brutus emphasized that the Constitution should be “adopted or rejected upon a fair discussion of its merits.”[4] In his final essay written prior to the election of delegates to the Poughkeepsie convention,[5] Smith (writing as Plebeian) declared “[l]et the constitution stand on its own merits.”[6]Indeed, the very first sentence of Brutus 1 began by emphasizing the magnitude of the “question” that the public was being called upon “to investigate.”[7] Likewise, the opening sentence of Brutus 3 reiterated that “[i]n the investigation of this constitution, under your consideration, great care should be taken, that you do not form your opinions respecting it, from unimportant provisions, or fallacious appearances.”[8]

For the past two hundred years historians have disagreed over Brutus’s identity. Yet, generations of historians have agreed that Brutus’s pseudonymous essays were among the “most powerful and well-reasoned Antifederalist writing.”[9] In particular, historians have pointed to Brutus’s logical reasoning as a distinguishing feature of his writing style. For example, in the 1960s Cecelia M. Kenyon noted that Brutus’s letters were “outstanding for their logical development of possible implications and ramifications specific legal clauses in the constitution.”[10] Pointing to Brutus 6, Kenyon observed that Brutus’s “logic is powerful.” In 1965, Morton Borden published The Anti-Federalist Papers, eighty-five Antifederalist essays intended to illustrate Antifederalist responses to each of the eight-five Federalist Papers. For Borden, Brutus’s “reasoning” was “impressive,” “well structured,” and offered “uncommon foresight.”[11] More recently, Pauline Maier observed that Brutus “offered tight, closely reasoned arguments” which were central to the Antifederalist case against the Constitution.[12] This analysis of Brutus’s logical writing style fully aligns with descriptions of Melancton Smith’s convention speeches.

A young James Kent, who would go on to become one of the nation’s foremost jurists, observed Smith in action during the New York ratification convention. In Kent’s view, Alexander Hamilton was “indisputably pre-eminent.” Yet, Smith was “equally the most prominent and the most responsible speaker on the Anti-Federalist side of the Convention.” According to Kent, nobody “compared to Smith in his powers of acute and logical discussion,” notwithstanding his “dry, plain and syllogistic” speaking style.[13] This contemporary description of Smith, is entirely consistent with descriptions by historians of both Smith and Brutus.

Ron Chernow notes that Smith was “a deceptively good debater who knew how to lure opponents into logical traps from which they found it hard to escape.”[14] Pointing to similarities between Smith’s speeches and Brutus, David J. Siemers argues that Smith evidenced the “same kind of attention to detail and depth of argument characteristic of Brutus.”[15]As discussed below, Brutus frequently supported his arguments with maxims and axioms, which perfectly aligns with Smith’s speeches. By contrast, Smith opined that one of the leading Federalist speakers, Chancellor Robert R. Livingston, was a “wretched reasoner.”[16] Accordingly, the symmetry between the logical reasoning style of Smith and Brutus is useful attribution evidence that helps confirm the “Brutus – Melancton Smith Authorship Thesis.”[17]

Overview of Brutus Attribution

This blog post is the fourth of a multi-part series exploring the authorship of the sixteen letters of Brutus. The “Brutus – Melancton Smith Authorship Thesis” argues that Brutus was Melancton Smith, Alexander Hamilton’s chief opponent at the New York ratification convention in Poughkeepsie. Part 1 provided an overview of existing scholarship and a summary of the new evidence compiled by Statutesandstories.com in collaboration with John P. Kaminski. Parts 2 and 3 set forth the detailed attribution evidence summarized in Part 1.

Part 2 focused on pre-authorship attribution evidence arising prior to the printing of the Brutus essays from 18 October 1787 to 10 April 1788. Part 3 continued with a discussion of post-authorship attribution evidence primarily arising from Smith’s speeches at the New York ratification convention.[18] Part 4 below focuses on Smith’s syllogistical reasoning style which aligns with Brutus. Part 5 will discuss newly uncovered speeches by Melancton Smith which further confirm Melancton Smith’s identity as Brutus.

The “Brutus – Melancton Smith Authorship Thesis” is based on a detailed review of decades of correspondence, pamphlets, legislative history, records of the New York ratification convention, and recently uncovered speeches by Smith. Much of this work is only made possible after the completion of the monumental forty-seven volumes of the Documentary History of the Ratification of the Constitution (DHRC). Readers are advised that Parts 2 and 3 are not intended to be a quick read. Unlike more traditional and reader friendly blog posts, Parts 2 and 3 might best be consumed in digestible installments.

Earlier this year, Statutesandstories.com released a related seven-part series about the Antifederalist Federal Farmer. Historians have long recognized Brutus and the Federal Farmer as the two most important Antifederalist authors. For decades, the Federal Farmer was believed to have been Richard Henry Lee. In 1974, historian Gordon Wood challenged this longstanding attribution, but did not offer a replacement author. In 1988, John P. Kaminski released a paper arguing that Elbridge Gerry was the Federal Farmer. Click here for a link to the Federal Farmer – Elbridge Gerry Authorship Thesis (“FEAT”) which surveys newly uncovered evidence that Gerry was in fact the Federal Farmer. With Gerry confirmed as the Federal Farmer, the field is cleared for Melancton Smith to be recognized as Brutus.

Brutus – Part 2 was organized into the following categories of attribution evidence:

- Smith’s 1784 pamphlet opposing the holding in the case of Rutgers v. Waddington which made Smith a leading early critic of judicial review;

- the choice of the pseudonym Brutus and Smith’s political rivalry with Alexander Hamilton;

- Smith’s 1786 speech to Congress defending New York’s conditional adoption of the impost requested by Congress;

- Smith’s two pamphlets as A Republican defending New York’s conditional approval of the impost;

- the nexus and political relationship between Smith and New York Governor George Clinton, as evidenced in Charles Tillinghast’s letter to Hugh Hughes dated 27 January 1788; and

- logistical considerations which place Smith in Brutus’s

Brutus – Part 3 continued with a discussion of the additional attribution evidence which flows in large part from Smith’s speeches at the New York ratification convention in June and July of 1788:

- Brutus’s frequent use of biblical references which aligns with Smith’s biography as an “ardent Presbyterian” and “pillar of his church”;

- Smith’s ardent and abiding opposition to slavery which aligns with Brutus;

- Smith’s linguistic fingerprints (words and phrases reoccurring in Smith’s correspondence and speeches) which align with Brutus.

Brutus – Part 4 below presents the remaining categories of attribution evidence which connect Smith to Brutus:

- Smith’s logical and syllogistic reasoning style which aligns with Brutus;

- Brutus’s lack of insider knowledge relating to the Constitutional Convention, in contrast to the Federal Farmer;

- Brutus’s intimate knowledge of the workings of the Confederation Congress which aligns with Smith’s service in Congress beginning in 1785.

In an effort to avoid duplication, Part 4 assumes knowledge on the part of readers, who are encouraged to click on bolded links to prior blog posts and related primary sources. As was the case with Parts 2 and 3, Part 4 contains relatively dense material. For this reason, Part 4 might best be consumed in digestible installments.

Brutus’s syllogistic reasoning style aligns with Smith

In his June 20 speech Melancton Smith invoked foundational principles of logical reasoning, which he hoped both sides would observe. Smith suggested that “premises should be laid down previously to the drawing of any conclusion.”[19]This admonition harkens back to the same observation by Brutus 10: “I confess, I cannot perceive that the conclusion follows from the premises. Logicians say, it is not good reasoning to infer a general conclusion from particular premises.”[20] The focus of Brutus 10 was the danger posed by large standing armies. In responding to Federalist 24’s defense of standing armies, Brutus 10 employed the following logical technique: he simplified and restated the Federalist argument “striped of the abundant verbages with which the author has dressed it.”[21]

This identical strategy was described by Smith on June 21, in another early convention speech. The following passage provides a window into Smith’s thinking and logical mind. Smith explained his approach to “fair reasoning” as follows:

In most pol. opinions there will be variant opinions amongst men of understg.—Each will support their sentiments in the best manner their abilities will enable them—It frequently happens that superior talentsare engaged on the one side against plain common sense on the other—But no abilities can change the nature of things—or make truth falsehood or the contrary—Every man who will think for himself, will weigh the arguments offered on both sides, and judge for himself—He will strip them of the verbage with which they are clothed, and seperate them from the artful specious forms they may assume & from the agreeable manner in which they are presented—and careful examine whether they point to the object, or to something else.

In other words, the New York voters addressed by Brutus (and the convention delegates addressed by Smith) should see beyond the superficial “superior talents” of the Federalist proponents and use “plain common sense.”[22] Each voter/delegate should “think for himself” and strip arguments of the “verbiage with which they are clothed” to identify “specious” arguments, regardless of the “agreeable manner in which they are presented.”

Similarly, Brutus 3 reasoned, “if the clause, which provides for this branch, be stripped of its ambiguity, it will be found that there is really no equality of representation, even in this house.” This aligns with Plebeian who sought to strip a Federalist argument of its “artificial coloring.” Indeed, the use of the phraseology of “stripping” an argument / language from its “verbiage,” “ambiguity,” or “colouring” is properly viewed as a signature Brutus/Smith fingerprint.[23]

The goal was to “carefully examine” whether an argument supported the “object” / “end,” using premises to establish a conclusion. Smith continued that voters/delegates should disregard – and not give “weight” to – Federalist rhetoric which was contrary to longstanding and respected “writers & reasoners” on a subject:

—It will have no weight wt him, for a person to charge those who differ from him, with having wrong Ideas—that it is high time we shd. reason right—That his opinions are contrary to that of all writers & reasoners on the subject—that talking of danger to Liberty is mere verbage—that to a mind no[t] predisposed, his Arguts. are conclusive—that his apprehensions of danger to Liberty is fanciful—These and every thing of that Kind will pass wt. a man who reasons for himself as mere verbage—There is no reason to use this method on the part of those who advocate the Const—because if truth is on their side, they have ability & skill to support it, by fair reasoning—many of them have been in the habit of public speaking—and are [– – –] for their talents—It gives room to suspect, their cause not very good, when the ablest men in advocy. abound in such assertn instd. of Argt.—

This rhetorical device of stripping away “mere verbiage,” evaluating “objects” / “ends,” and testing whether a “means” was necessary to establish/answer an object/end was used by Smith and Brutus alike. As stated by Brutus 5, “the means should be suited to the end; a government should be framed with a view to the objects to which it extends.”[24] As described in Brutus – Part 2, Smith used this same logical strategy during the impost debate in Congress in 1786:

- Smith identified a question

- Smith evaluated whether the means answer/achieve the end/object/purpose/goal

- Smith identified relevant observations

- Smith asked follow-up questions

- Smith connected the dots between premises and conclusions, explaining what has been “shewn” (and/or what the evidence “shews”).

The following examples demonstrate this pattern of logical argument repeatedly used by Brutus’s essays and Smith’s convention speeches. To be sure, the Federal Farmer, Publius and others also attempted to employ logical reasoning. Nevertheless, as demonstrated below, other writers do not employ the same logical devices as effectively, consistently or with the same frequency as Brutus.

Terminology of logical reasoning: “maxims,” “axioms,” “therefore,” “hence” and it is “evident”

Brutus would commonly reason from premises which were connected by “maxims” / “axioms” or other evidence to deduce a conclusion. Brutus would often signify the resulting conclusion with the conjunctive adverb “therefore.” This is standard practice for deductive reasoning. The same pattern of logical reasoning is evident in Melancton Smith’s speeches.[25] In the sixteen Brutus essays the word “therefore” was used eighty-two times, with a frequency of 5.125 times per essay. By contrast, Federal Farmer and Publius were significantly less likely to use the word “therefore” compared to Brutus. The following chart compares the frequency of the use of the word “therefore” by all three writers.

|

Usage of the word “therefore” |

||

| Brutus (16 essays) | Federal Farmer (18 essays) | Publius (85 essays) |

| 82 (out of 44,134 words) | 55 (out of 67,013 words) | 138 (out of 193,138 words) |

| 5.13 times per essay | 3.05 times per essay | 1.62 times per essay |

| frequency of .186%[26] | frequency of .082% | frequency of .071% |

Set forth below are examples of arguments by Brutus and Melancton Smith speeches using the word “therefore.”

- Brutus 1: [T]he legislature have authority to contract debts at their discretion; they are the sole judges of what is necessary to provide for the common defence, and they only are to determine what is for the general welfare; this power therefore is neither more nor less, than a power to lay and collect taxes, imposts, and excises, at their pleasure;

- Brutus 2: The powers, rights, and authority, granted to the general government by this constitution, are as complete, with respect to every object to which they extend, as that of any state government—It reaches to every thing which concerns human happiness—Life, liberty, and property, are under its controul. There is the same reason, therefore, that the exercise of power, in this case, should be restrained within proper limits, as in that of the state governments.

- Brutus 5: And in the last paragraph of the same section there is an express authority to make all laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into execution this power. It is therefore evident, that the legislature under this constitution may pass any law which they may think proper.

- Brutus 5: The great and only security the people can have against oppression from this kind of taxes, must rest in their representatives. If they are sufficiently numerous to be well informed of the circumstances, and ability of those who send them, and have a proper regard for the people, they will be secure. The general legislature, as I have shewn in a former paper, will not be thus qualified, and therefore, on this account, ought not to exercise the power of direct taxation.

- Brutus 6: Suppose then that both governments should lay taxes, duties, and excises, and it should fall so heavy on the people that they would be unable, or be so burdensome that they would refuse to pay them both—would it not be necessary that the general legislature should suspend the collection of the state tax? It certainly would. For, if the people could not, or would not pay both, they must be discharged from the tax to the state, or the tax to the general government could not be collected.—The conclusion therefore is inevitable, that the respective state governments will not have the power to raise one shilling in any way, but by the permission of the Congress.

- Brutus 7: It has been shewn, that no such allotment is made in this constitution, but that every source of revenue is under the controul of the Congress; it therefore follows, that if this system is intended to be a complex and not a simple, a confederate and not an entire consolidated government, it contains in it the sure seeds of its own dissolution.

- Brutus 8: It may possibly happen that the safety and welfare of the country may require, that money be borrowed, and it is proper when such a necessity arises that the power should be exercised by the general government.—But it certainly ought never to be exercised, but on the most urgent occasions, and then we should not borrow of foreigners if we could possibly avoid it. The constitution should therefore have so restricted, the exercise of this power as to have rendered it very difficult for the government to practise it.

- Brutus 14: They will therefore have the same authority to determine the fact as they will have to determine the law, and no room is left for a jury on appeals to the supreme court.

- June 21 convention speech: [W]e are not to expect that the house of representatives will be inclined to enlarge the numbers. The same motive will operate to influence the president and senate to oppose the increase of the number of representatives; for in proportion as the weight of the house of representatives is augmented, they will feel their own diminished: It is therefore of the highest importance that a suitable number of representatives should be established by the constitution.

In particular, Brutus regularly used the phrase “and therefore.” In the sixteen Brutus essays the phrase “and therefore” is used a remarkable thirteen times. In comparison, Federal Farmer and Publius only used the phrase “and therefore” eight times each. Not surprisingly, Smith used the phrase “and therefore” twice in the Plebeian pamphlet. It thus follows that the phrase “and therefore” was a consistent fingerprint which helps identify Smith and Brutus. The frequency of this pattern is illustrated by the following chart.

|

Usage of the phrase “and therefore” |

||

| Brutus (16 essays) | Federal Farmer (18 essays) | Publius (85 essays) |

| 13 times | 8 times | 8 times |

| 81% of Brutus essays | 44% of Federal Farmer essays | 9% of Federalist essays |

As discussed in Part 3, Plebeian can properly be considered as Smith’s “final” Brutus essay (and a magnum opus of sorts), timed to correspond with the pending election of delegates to Poughkeepsie.[27] The average Brutus essay was approximately 2,758 words long. By contrast, Smith’s Plebeian pamphlet contained 9,521 words. The word “therefore” is used twelve times by Plebeian, with a frequency of .126%. Thus, the frequent use of the word “therefore” by Plebeian aligns with Brutus at .186%. By contrast, Federal Farmer and Publius were less likely to use the word “therefore” with a frequency of .082% and .071%, respectively.

In addition to using “therefore,” Brutus and Smith also used the deductive connector “hence,” which similarly introduces a conclusion which logically flows from given premises. This pattern repeats in Smith’s convention speeches along with the recently discovered speeches which will be discussed in Part 5.

Brutus used the word “hence” ten times in sixteen essays. Brutus 9 and 16 use “hence” twice in a single essay. On average, the word “hence” is used in 63% of the Brutus essays compared to 44% and 36% of Federal Farmer and Federalist essays. The results of this analysis are set forth in the following chart which demonstrates that Brutus used the conjunctive adverb “hence” with a greater frequency than Federal Farmer and Publius.

|

Usage of the word “hence” |

||

| Brutus (16 essays) | Federal Farmer (18 essays) | Publius (85 essays) |

| 10 (out of 44,134 words) | 8 (out of 67,013 words) | 31 (out of 193,138 words) |

| average of 63% of essays[28] | average of 44% of essays | average of 36% of essays |

| frequency of .023% | frequency of .012% | frequency of .016% |

Set forth below are examples of Brutus using the adverb “hence:”

- Brutus 1: “The different parts of so extensive a country could not possibly be made acquainted with the conduct of their representatives, nor be informed of the reasons upon which measures were founded. The consequence will be, they will have no confidence in their legislature, suspect them of ambitious views, be jealous of every measure they adopt, and will not support the laws they pass. Hence the government will be nerveless and inefficient, and no way will be left to render it otherwise, but by establishing an armed force to execute the laws at the point of the bayonet—a government of all others the most to be dreaded.”

- Brutus 2: “[T]he constitution of the United States, and the laws made in pursuance thereof, is the supreme law, and all legislatures and judicial officers, whether of the general or state governments, are bound by oath to support it. No priviledge, reserved by the bills of rights, or secured by the state governments, can limit the power granted by this, or restrain any laws made in pursuance of it. It stands therefore on its own bottom, and must receive a construction by itself without any reference to any other—And hence it was of the highest importance, that the most precise and express declarations and reservations of rights should have been made.”

- Brutus 9: “There are certain things which rulers should be absolutely prohibited from doing, because, if they should do them, they would work an injury, not a benefit to the people. Upon the same principles of reasoning, if the exercise of a power, is found generally or in most cases to operate to the injury of the community, the legislature should be restricted in the exercise of that power, so as to guard, as much as possible, against the danger. Theseprinciples seem to be the evident dictates of common sense, and what ought to give sanction to them in the minds of every American, they are the great principles of the late revolution, and those which governed the framers of all our state constitutions. Hence we find, that all the state constitutions, contain either formal bills of rights, which set bounds to the powers of the legislature, or have restrictions for the same purpose in the body of the constitutions.”

- Brutus 16: “The legislative power should be in one body, the executive in another, and the judicial in one different from either—But still each of these bodies should be accountable for their conduct. Hence it is impracticable, perhaps, to maintain a perfect distinction between these several departments.”

- July 23 convention speech: “It is not more generally agreed that Union is necessary than that the old confederation is unfit for procuring the ends of union, and while It has contributed to lay upon us the burthens of a national Government has Obtained for us few or none of the benefits of It, hence It is equally admitted that an important change in the system is necessary.”

- June 27 convention speech: “It is a general maxim, that all governments find a use for as much money as they can raise. Indeed they have commonly demands for more: Hence it is, that all, as far as we are acquainted, are in debt.”

In logical reasoning, a maxim or axiom is a principle that can be used as a premise to support an argument. The word “maxim” appears in Brutus 6, 11, 14, 16. Smith referred to “maxim(s)” in his speeches on June 20, 21, 25, 27, & 30.[29]He used the interchangeable term “axiom” in Brutus 6, 8 and 9. Examples of the use of maxims / axioms by Brutus, Plebeian and Smith are set forth below:

- Brutus 11: “Every body of men invested with office are tenacious of power; they feel interested, and hence it has become a kind of maxim, to hand down their offices, with all its rights and privileges.”

- Brutus 16: “It has been a long established maxim, that the legislative, executive and judicial departments in government should be kept distinct. It is said, I know, that this cannot be done. And therefore that this maxim is not just, or at least that it should only extend to certain leading features in a government. I admit that this distinction cannot be perfectly preserved. In a due ballanced government, it is perhaps absolutely necessary to give the executive qualified legislative powers, and the legislative or a branch of them judicial powers in the last resort. It may possibly also, in some special cases, be adviseable to associate the legislature, or a branch of it, with the executive, in the exercise of acts of great national importance. But still the maxim is a good one, and a separation of these powers should be sought as far as is practicable.”

- June 20 convention speech: “Axiom that Body who has all power and both purse and Sword has the absolute Govt. of all other Bodies and they must exist at the will & pleasure of the Superior.”

- June 21 convention speech: “If therefore this maxim be true, that men are unwilling to relinquish powers which they once possess, we are not to expect that the house of representatives will be inclined to enlarge the numbers.”

- June 30 convention speech: “we are not to conclude yt all his assertions are axiams, but weigh arguments in an impartial scale of reason”[30]

- Plebeian: “[W]hen a government is once in operation, it acquires strength by habit, and stability by exercise. If it is tolerably mild in its administration, the people sit down easy under it, be its principles and forms ever so repugnant to the maxims of liberty.—It steals, by insensible degrees, one right from the people after another, until it rivets its powers so as to put it beyond the ability of the community to restrict or limit it.”

- Plebeian: “These observations are so well-founded, that they are become a kind of axioms in politics; and the inference to be drawn from them is equally evident, which is this,—that, in forming a government, care should be taken not to confer powers which it will be necessary to take back.”

The expression that it is “evident” is used in logical reasoning when a conclusion has been logically proven by a valid argument[31] or is self-evident. As evidenced by the following chart, Brutus used the word “evident” / “evidently” twenty-one times. The word “evident” / “evidently” was used four times by Plebeian.[32] This pattern, however, is not unique to Brutus / Plebeian, as Federal Farmer and Publius also make frequent use of this phraseology. Smith used the word “evident” / “evidently” in speeches on June 20, 21, 26, 27 and July 23. Hamilton used this phraseology in speeches on June 21, 24, 27 and July 12.

|

Usage of the word “evident” / “evidently” |

||

| Brutus (16 essays) | Federal Farmer (18 essays) | Publius (85 essays) |

| 21 (out of 44,134 words) | 25 (out of 67,013 words) | 88 (out of 193,138 words) |

| 1.3 times per essay | 1.39 times per essay | 1.04 times per essay |

| frequency of .048% | frequency of .037% | frequency of .046% |

Examples of the use of the word “evident” / “evidently” by Brutus, Plebeian and Smith are set forth below:

- Brutus 1: “[I]t is a truth confirmed by the unerring experience of ages, that every man, and every body of men, invested with power, are ever disposed to increase it, and to acquire a superiority over every thing that stands in their way. This disposition, which is implanted in human nature, will operate in the federal legislature to lessen and ultimately to subvert the state authority, and having such advantages, will most certainly succeed, if the federal government succeeds at all. It must be very evident then, that what this constitution wants of being a complete consolidation of the several parts of the union into one complete government, possessed of perfect legislative, judicial, and executive powers, to all intents and purposes, it will necessarily acquire in its exercise and operation.”

- Brutus 2: “If we may collect the sentiments of the people of America, from their own most solemn declarations, they hold this truth as self evident, that all men are by nature free. No one man, therefore, or any class of men, have a right, by the law of nature, or of God, to assume or exercise authority over their fellows.”

- Brutus 5: “And in the last paragraph of the same section there is an express authority to make all laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into execution this power. It is therefore evident, that the legislature under this constitution may pass any law which they may think proper.”

- Brutus 7: “The most important end of government then, is the proper direction of its internal police, and œconomy; this is the province of the state governments, and it is evident, and is indeed admitted, that these ought to be under their controul. Is it not then preposterous, and in the highest degree absurd, when the state governments are vested with powers so essential to the peace and good order of society, to take from them the means of their own preservation?”

- Brutus 16: “It farther appears to me proper, that the legislatures should retain the right which they now hold under the confederation, of recalling their members. It seems an evident dictate of reason, that when a person authorises another to do a piece of business for him, he should retain the power to displace him, when he does not conduct according to his pleasure.”

- Plebeian: “The history of the world furnishes many instances of a people’s increasing the powers of their rulers by persuasion, but I believe it would be difficult to produce one in which the rulers have been persuaded to relinquish their powers to the people. Wherever this has taken place, it has always been the effect of compulsion. These observations are so well-founded, that they are become a kind of axioms in politics; and the inference to be drawn from them is equally evident, which is this,—that, in forming a government, care should be taken not to confer powers which it will be necessary to take back; but if you err at all, let it be on the contrary side, because it is much easier, as well as safer, to enlarge the powers of your rulers, if they should prove not sufficiently extensive, than it is to abridge them if they should be too great.”

- June 20 convention speech: “Evident that except in Small Districts all Men cannot meet to regulate Governmt. Hence Representation”

“fair reasoning” v. “specious and false reasoning” to “prove” a conclusion

In his sixteen essays Brutus discusses “reasoning” nineteen times.[33] Not surprisingly, Smith also refers to “reasoning” twice in Plebeian. By contrast, in eighteen essays, the Federal Farmer only uses the word “reasoning” five times. Similarly, in eighty-five essays, Publius uses the word “reasoning” only twenty-seven times, a substantially lower frequency than Brutus. A comparison of the use of the word “reasoning” is illustrated in the following table:

|

Usage of the word “reasoning” |

||

| Brutus (16 essays) | Federal Farmer (18 essays) | Publius (85 essays) |

| 19 (out of 44,134 words) | 5 (out of 67,013 words) | 27 (out of 193,138 words) |

| 1.188 times per essay | .278 times per essay | .318 times per essay |

| frequency of .043% | frequency of .007% | frequency of .014% |

This same pattern continues in Smith’s Plebeian pamphlet. The frequency of Plebeian’s usage of the word “reasoning” is .021% of all words, which is higher than Federal Farmer at .007% and Publius of .014%.

It stands to reason that Melancton Smith would also discuss “reasoning” in his speeches. Smith does so on June 20, 21, 23, 25, 26, 27, 30, July 1 and 2.[34] Brutus 10 contains a useful illustration of how Smith understood “good” logical reasoning should operate. “I confess, I cannot perceive that the conclusion follows from the premises. Logicians say, it is not good reasoning to infer a general conclusion from particular premises: though I am not much of a Logician, it seems to me, this argument is very like that species of reasoning.”

The following examples illustrate Smith’s repeated use of the word “reasoning” as Brutus and during the New York ratification convention:

- Brutus 6: “To apply this reasoning…But does it thence follow….”

- Brutus 6: “To say…and from hence to infer…is not conclusive reasoning”;

- Brutus 8: “If this great man’s reasoning be just, it follows….”

- Brutus 9: “Upon the same principles of reasoning…”

- Brutus 9: “This reasoning supposes… But such an idea is groundless and absurd”

- Brutus 10: “Logicians say, it is not good reasoning to infer a general conclusion from particular premises: though I am not much of a Logician, it seems to me, this argument is very like that species of reasoning”; “this reasoningmight have weight; but this has not been proved nor can it be”

- June 20 convention speech: “That this was the case could be proved without any long chain of reasoning”

- June 26 convention speech: “the gentleman’s reasoning is directly against himself”

- June 27 convention speech: “we are very liable to err in theoretical reasonings on political questions”

- July 2 convention speech: “It is the reasoning among all reasoners, that nothing to something adds nothing.”

Brutus and Smith also distinguished between “fair reasoning” and “specious” reasoning. Neither Federal Farmer nor Publius use the phrase “fair reasoning” which is used by Smith during the ratification debates on June 21 and June 23. Examples of the use of the phrase “fair reasoning,” “reasoning fairly,” “sober reasoning,” and “curious reasoning” by Brutus and Smith are set forth below:

- Brutus 9: “The man who reproves another for a fault, should be careful that he himself be not guilty of it. How far this writer has manifested a spirit of candour, and has pursued fair reasoning on this subject, the impartial public will judge, when his arguments pass before them in review.”

- June 21 convention speech: “These and every thing of that Kind will pass wt. a man who reasons for himself as mere verbage—There is no reason to use this method on the part of those who advocate the Const—because if truth is on their side, they have ability & skill to support it, by fair reasoning—many of them have been in the habit of public speaking—and are [– – –] for their talents—It gives room to suspect, their cause not very good, when the ablest men in advocy. abound in such assertn instd. of Argt.”

- June 23: The honorable gentleman next animadverts on my apprehensions of corruption, and instances the present Congress, to prove an absurdity in my argument. But is this fair reasoning?”

- June 20 convention speech: “And after all, said he, we shall find that both these allusions are taken from the same vision; and their true meaning must be discovered by sober reasoning.”

- July 2 convention speech: “I submit to the candor of the committee, whether any evidence of the strength of a cause is afforded, when gentlemen, instead of reasoning fairly, assert roundly; and use all the powers of ridicule and rhetoric, to abuse their adversaries.”

Examples of the use of the phrase “specious” reasoning by Brutus and Smith are set forth below:

- Brutus 2: “It requires but little attention to discover, that this mode of reasoning is rather specious than solid.”

- Brutus 3: “On a careful examination, you will find, that many of its parts, of little moment, are well formed; in these it has a specious resemblance of a free government—but this is not sufficient to justify the adoption of it—the gilded pill, is often found to contain the most deadly poison.”

- Brutus 4: “To effect their purpose, they will assume any shape, and, Proteus like, mould themselves into any form—where they find members proof against direct bribery or gifts of offices, they will endeavor to mislead their minds by specious and false reasoning, to impose upon their unsuspecting honesty by an affectation of zeal for the public good”

- Brutus 6: “This same writer insinuates, that the opponents to the plan promulgated by the convention, manifests a want of candor, in objecting to the extent of the powers proposed to be vested in this government; because he asserts, with an air of confidence, that the powers ought to be unlimited as to the object to which they extend; and that this position, if not self-evident, is at least clearly demonstrated by the foregoing mode of reasoning. But with submission to this author’s better judgment, I humbly conceive his reasoning will appear, upon examination, more specious than solid.”

- June 21 convention speech: “Every man who will think for himself, will weigh the arguments offered on both sides, and judge for himself—He will strip them of the verbage with which they are clothed, and seperate them from the artful specious forms they may assume & from the agreeable manner in which they are presented—and careful examine whether they point to the object, or to something else”

The purpose of logical reasoning is to provide proof for an argument. Brutus repeatedly used the word “prove” / “proved” in making his arguments and prove his points. This pattern aligns with Smith’s convention speeches on June 20, June 21, June 23, June 25, June 26, June 27, June 28, and July 1. As demonstrated in the following chart, Brutus used this phraseology with greater frequency than Federal Farmer or Publius. Likewise, Plebeian’s use of this terminology with a frequency of .053% aligns with Brutus at .057%, compared to Federal Farmer at .031% and Publius at .028%.

|

Usage of the word “prove” / “proved” |

||

| Brutus (16 essays) | Federal Farmer (18 essays) | Publius (85 essays) |

| 25 (out of 44,134 words) | 21 (out of 67,013 words) | 54 (out of 193,138 words) |

| 1.6 times per essay | 1.2 times per essay | .6 times per essay |

| frequency of .057% | frequency of .031% | frequency of .028% |

Examples of Brutus/Smith using the word “prove” / “proved” are set forth below:

- Brutus 2: “the instances adduced, are sufficient to prove, that this argument is without foundation.”

- Brutus 4: “Though this truth is proved by almost every page of the history of nations….”

- Brutus 6: “I have, in my former papers, offered a variety of arguments to prove, that a simple free government could not be exercised over this whole continent…”

- Brutus 6: “In my last number I called your attention to this subject, and proved, as I think, uncontrovertibly, that the powers given the legislature under the 8th section of the 1st article, had no other limitation than the discretion of the Congress.”

- Brutus 10: “….then this reasoning might have weight; but this has not been proved nor can it be.”

- Brutus 15: “To prove this I will shew…”

- June 20 convention speech: “That this was the case could be proved without any long chain of reasoning”

- June 21 convention speech: “Common observation and experience prove the existence of such distinctions.”

- June 23 convention speech: “The honorable gentleman next animadverts on my apprehensions of corruption, and instances the present Congress, to prove an absurdity in my argument. But is this fair reasoning?”

- June 25 convention speech: “But the whole reasoning of the gentlemen rests upon the principle that the states will be able to check the general government, by exciting the people to opposition: It only goes to prove, that the state officers will have such an influence over the people, as to impell them to hostility and rebellion.”

- June 27 convention speech: “It is unnecessary that I should enter into a minute detail, to prove that these complex powers cannot operate peaceably together, and without one being overpowered by the other.”

- June 30 convention speech: “Mr. Smith then went into an examination of the particular provisions of the constitution, and compared them together, to prove that his remarks were not conclusions from general principles alone, but warranted by the language of the constitution.”

“absurd” / “absurdity”

Given his plain spoken demeanor it may come as a surprise to readers that Brutus periodically referred to Federalist arguments as absurd. Smith’s doing so should not be viewed as an ad hominem personal attack. Rather, Smith has been described as having “the most gentle, liberal, and amiable disposition.”[35] When calling an argument absurd, Smith was invoking a particular meaning applicable to logical reasoning. Noah Webster’s first dictionary published in 1806 defines the word absurd as “contrary to reason, foolish, inconsistent.”[36] The word absurdity is defined by Webster as “unreasonableness, inconsistency.” Moreover, the logical technique, reductio ad absurdum, attempts to demonstrate a contention by the absurd consequences which flow from premises as a matter of logical necessity.

The word “absurd” / “absurdity” is used nine times by Brutus with a frequency of .02% and four times by Plebeian with a frequency of .04%. This frequency is demonstrably higher than the use of the word “absurd” / “absurdity” by Federal Farmer (.005%) or Publius (.01%). Smith used the word “absurd” / “absurdity” in convention speeches on June 20, 21 and 23. He also uses the word “absurd” in newly transcribed notes of his speech of June 30.

|

Usage of the word “absurd,” “absurdity,” & “absurdities” |

||

| Brutus (16 essays) | Federal Farmer (18 essays) | Publius (85 essays) |

| 9 (out of 44,134 words) | 3 (out of 67,013 words) | 20 (out of 193,138 words) |

| .56 times per essay | .17 times per essay | .24 times per essay |

| frequency of .02% | frequency of .005% | frequency of .01% |

Examples of Brutus / Smith using the word “absurd” / “absurdity” are set forth below:

- Brutus 3: “The very term, representative, implies, that the person or body chosen for this purpose, should resemble those who appoint them…They are the sign—the people are the thing signified. It absurd to speak of one thing being the representative of another, upon any other principle.”

- Brutus 5: “There cannot be a greater solecism in politics than to talk of power in a government, without the command of any revenue. It is as absurd as to talk of an animal without blood, or the subsistence of one without food.”

- Brutus 5: “Indeed the idea of any government existing, in any respect, as an independent one, without any means of support in their own hands, is an absurdity.”

- Brutus 6: “It is as absurd to say, that the power of Congress is limited by these general expressions, ‘to provide for the common safety, and general welfare,’ as it would be to say, that it would be limited, had the constitution said they should have power to lay taxes, &c. at will and pleasure.”

- Brutus 7: “Is it not then preposterous, and in the highest degree absurd, when the state governments are vested with powers so essential to the peace and good order of society, to take from them the means of their own preservation?”

- Brutus 8: “It seems to me as absurd, as it would be to say, that I was free and independent, when I had conveyed all my property to another, and was tenant to will to him, and had beside, given an indenture of myself to serve him during life.”

- Brutus 9: “But this author supposes, that no danger is to be apprehended from the exercise of this power, because, if armies are kept up, it will be by the people themselves, and therefore, to provide against it, would be as absurdas for a man to ‘pass a law in his family, that no troops should be quartered in his family by his consent.’ This reasoning supposes, that the general government is to be exercised by the people of America themselves—But such an idea is groundless and absurd.”

- June 20 convention speech: “The principle of a representation, being that every free agent should be concerned in governing himself, it was absurd to give that power to a man who could not exercise it—slaves have no will of their own”

- June 21 convention speech: “To say, as this gentleman does, that our security is to depend upon the spirit of the people, who will be watchful of their liberties, and not suffer them to be infringed, is absurd. It would equally prove that we might adopt any form of government.”

- June 23 convention speech: “The honorable gentleman next animadverts on my apprehensions of corruption, and instances the present Congress, to prove an absurdity in my argument. But is this fair reasoning?”

Brutus’s lack of insider knowledge compared to the Federal Farmer and Publius

Unlike other states that appointed larger delegations, New York only sent three delegates to the Constitutional Convention. Melancton Smith was not one of them. It thus follows that Brutus lacked access to details of the Convention, which only would have been known by attendees.[37] By contrast, two of the three authors of the Federalist (Madison and Hamilton) attended the Convention. Likewise, Federal Farmer (Gerry) was an active convention delegate. Access to insider information – or the lack thereof – provides significant attribution evidence that Elbridge Gerry was the Federal Farmer and Melancton Smith was Brutus.

For decades, historians have recognized that the Federal Farmer had access to insider information from the Constitutional Convention. In 1974 Gordon Wood published a paper challenging the conventional wisdom that Richard Henry Lee was the Federal Farmer. One of the arguments raised by Wood was the fact that the Federal Farmer “demonstrated an insider’s knowledge of the proceedings of the Philadelphia Convention.”[38] Although Wood did not propose an alternative author to replace Lee, Wood suggested that the Federal Farmer was likely a New Yorker. To this day, many historians believe that New Yorker, Melancton Smith, was the Federal Farmer.

In 1988 John P. Kaminski offered another alternative, a northerner from Massachusetts who frequently traveled to New York and was married to a New Yorker: Elbridge Gerry. Unlike Smith, Gerry was a delegate to the Constitutional Convention. Among other evidence, Kaminski’s attribution cites to the Federal Farmer’s knowledge “about what transpired during the secret meetings of the Convention.”[39]

While Kaminski’s attribution is in itself compelling, Statutesandstories has uncovered additional evidence which helps confirm the conclusion that Elbridge Gerry was in fact the Federal Farmer. Earlier this year, Statutesandstories.com published a seven-part series setting forth the Federal Farmer – Elbridge Gerry Authorship Thesis (“FEAT”), which builds on Kaminski’s work. Recent discoveries regarding Gerry dovetail with the Brutus – Melancton Smith Authorship Thesis (the “Brulancton Thesis”).

Federal Farmer 3 provides useful examples of insider information known by its author (Gerry). Only a delegate would have direct knowledge about the “vast laboured attention” described by Federal Farmer 3. “There were various interests in the convention, to be reconciled, especially of large and small states; of carrying and non-carrying states: and of states more and states less democratic—vast laboured attention were by the convention bestowed on the organization of the parts of the constitution offered.”

Another example of insider information known by the Federal Farmer involves the debate over the size of Congress. Federal Farmer 3 observed that, “The convention found that any but a small house of representatives would be expensive, and that it would be impracticable to assemble a large number of representatives.” Reflecting his Antifederalist views, Gerry wanted a larger House of Representatives, but he was outvoted during the Convention.[40]

Federal Farmer 9 similarly shared insider information. The following passage recounted dramatic details of the closing day of the Convention when George Washington intervened to adjust the representation formula:

The Convention was divided on this point of numbers: at least some of its ablest members urged that instead of 65 representatives there ought to be 130 in the first instance. They fixed one representative for each 40,000 inhabitants, and at the close of the work, the president suggested, that the representation appeared to be too small and without debate, it was put at, not exceeding one for each 30,000.”

When the Convention made its last-minute change to the size of the House of Representatives at Washington’s urging, the Convention was agreeing with Gerry that representation thresholds needed to be expanded to make the House more democratic.[41]

The Federal Farmer’s discussion of presidential terms of office also evidenced insider information. Federal Farmer 14 noted that, “The Convention, it seems, first agreed that the President should be chosen for seven years, and never after to be eligible.”[42] Another useful example of insider information from the Convention can be found in Federal Farmer 1 which noted “the tenacity of the small states to have an equal vote in the senate.” Only a delegate would have first-hand knowledge of these details.

By contrast, the fact that Brutus did not manifest any insider knowledge from the Convention is evidence supporting the “Brutus – Melancton Smith Authorship Thesis.” In fact, Brutus rarely mentioned the Convention at all. This makes perfect sense. Unlike Gerry, Smith was not a Convention delegate. Moreover, the two New York Antifederalists who did attend the Convention departed early. After Robert Yates and John Lansing, Jr., left the Convention in mid- July, New York no longer had a functioning delegation.[43] Accordingly, Smith did not have access to any sympathetic New York colleagues who could share information about Convention deliberations from 10 July 10 to 17 September.

Brutus’s intimate knowledge of the workings of the Confederation Congress aligns with Smith’s service in Congress beginning in 1785

Although Brutus did have access to insider information from the Convention, he did demonstrate familiarity with the Confederation Congress. Significantly, Brutus’s observations align with Smith’s service in the Confederation Congress beginning in 1785. Likewise, Federal Farmer’s observations align with Gerry’s earlier service in the Continental Congress. For example, the Federal Farmer discussed the creation of the Articles of Confederation. Brutus doesn’t.

While both Gerry and Smith served in Congress, Smith only became a delegate in March of 1785.[44] By contrast Gerry served in the Continental Congress dating back to 1776.[45] Gerry was a signatory to both the Declaration of Independence and the Articles of Confederation.

The following excerpts from the Federal Farmer suggest first-hand knowledge dating back to the formation of the Confederation, which Smith wouldn’t have:

- Federal Farmer 1: “We find members of Congress urging alterations in the federal system almost as soon as it was adopted.”

- Federal Farmer 1: “The confederation was formed when great confidence was placed in the voluntary exertions of individuals, and of the respective states: and the framers of it, to guard against usurpation, so limited and checked the powers, that, in many respects, they are inadequate to the exigencies of the union.”

- Federal Farmer 11: “When the confederation was formed, it was considered essentially necessary that the members of congress should at any time be recalled by their respective states, when the states should see fit, and others be sent in their room.

In particular, Federal Farmer 18 speaks in the first person about the creation of the Articles of Confederation. Only Gerry was serving in Congress in 1781 when the Articles were signed by the final congressional delegation from Maryland,[46]not Smith:

The states all agreed about seven years ago. that the confederation should remain unaltered, unless every state should agree to alterations: but we now see it agreed by the convention, and four states, that the old confederacy shall be destroyed, and a new one, of nine states, be erected, if nine only shall come in. Had we agreed, that a majority should alter the confederation, a majority’s agreeing would have bound the rest: but now we must break the old league, unless all the states agree to alter, or not proceed with adopting the constitution.

Yet, Brutus reflects familiarity with subsequent periods of Congressional activity.[47] This is consistent with Smith’s service in the Confederation Congress beginning in 1785:

- Brutus 7: “It has been constantly urged by Congress, and by individuals, ever since, until lately, that had this revenue been appropriated by the states, as it was recommended, it would have been adequate to every exigency of the union.”

- Brutus 7: “A variety of amendments were proposed to this system, some of which are upon the journals of Congress, but it does not appear that any of them proposed to invest the general government with discretionary power to raise money.”

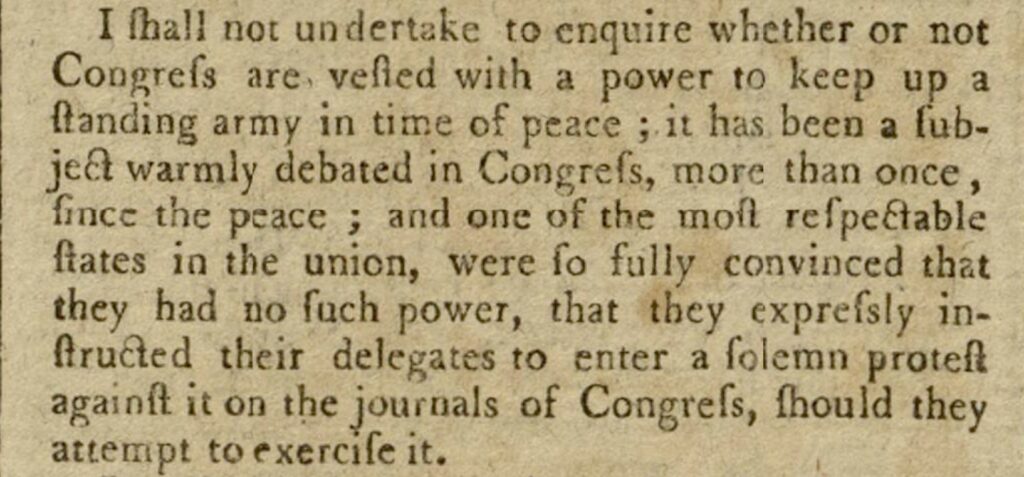

- Brutus 9: “I shall not undertake to enquire whether or not Congress are vested with a power to keep up a standing army in time of peace; it has been a subject warmly debated in Congress, more than once, since the peace; and one of the most respectable states in the union, were so fully convinced that they had no such power, that they expressly instructed their delegates to enter a solemn protest against it on the journals of Congress, should they attempt to exercise it.”[48]

Based on these passages, Brutus seemingly had access to the Journals of Congress. It is also likely that he was present during Congressional debates about revenue, as well as deliberations about a standing army, “a subject warmly debated in Congress.”[49] In particular, the debate over the Impost of 1783 was a focus of controversy in Congress in 1786. As discussed in Brutus – Part 2, Melancton Smith was not a passive observer during the impost battle between New York and Congress. When Congress debated whether to accept New York’s conditional adoption of the impost in 1786, Smith argued that New York’s substantial compliance should be accepted as sufficient.[50] In August of 1786 Congress asked Governor Clinton to reconsider his decision not to call a special session of the New York Assembly to reconsider its conditional adoption of the impost. Smith opposed doing so, arguing that “it would involve an interference of Congress” on a question respecting the construction of the New York Constitution upon which Congress has “no right to decide.”[51]

Use of the terms “Convention” / “plan” by Federal Farmer but not by Brutus suggests Federal Farmer (Gerry) was a delegate but Brutus (Smith) wasn’t

A striking distinction between Brutus, Federal Farmer and Publius is the number of times that they mentioned the Constitutional Convention. This makes perfect sense as Melancton Smith was not a Convention delegate whereas Elbridge Gerry, James Madison and Alexander Hamilton were.

|

Usage of the word “convention” |

||

| Brutus (16 essays) | Federal Farmer (18 essays) | Publius (85 essays) |

| 6 (out of 44,134 words) | 69 (out of 67,013 words) | 187 (out of 193,138 words) |

| .375 times per essay | 3.8 times per essay | 2.2 times per essay |

| frequency of .0136% | frequency of .103% | frequency of .097% |

This pattern is also evident with regard to the frequent use of the phrase “the plan of the convention”[52] by FederalFarmer and Publius compared to Brutus who never uses this phrase. Moreover, Brutus only uses the word “plan” a total of ten times, compared to Federal Farmer and Publius who use the term sixty-nine times and one hundred and eighty-seven times.

|

Usage of the word “plan”[53] |

||

| Brutus (16 essays) | Federal Farmer (18 essays) | Publius (85 essays) |

| 10 (out of 44,134 words) | 69 (out of 67,013 words) | 148 (out of 193,138 words) |

| .625 times per essay | 3.83 times per essay | 1.74 times per essay |

| frequency of .023% | frequency of .10% | frequency of .08% |

This post continues in Part 5 with a discussion of newly uncovered speeches by Melancton Smith which further confirm his identity as Brutus.

Endnotes

[1] The convention began on June 17 and ran through July 26. DHRC, 22:1669. Smith’s first substantive speech quoted above was delivered on June 20. DHRC, 22:1712.

[2] The sixteen Brutus essays were published in eighteen installments in the New York Journal between 18 October 1787 and 10 April 1788.

[3] DHRC, 19:105 (Brutus 1).

[4] DHRC, 22:154 (Brutus 2); 20:658 (Brutus 10).

[5] Melancton Smith played an active role organizing the Antifederalists leading into the April election. A supermajority of forty-six Antifederalists were elected compared to only nineteen Federalists. DHRC, 22:1669.

[6] DHRC, 20:962 (Plebeian).

[7] DHRC, 19:105 (Brutus 1).

[8] DHRC, 19:252 (Brutus 3). In addition to Brutus 1 and 3, Brutus 6, 11, 14 and 16 also repeatedly use their undertaking as investigating/investigation. Likewise, Melancton Smith uses the same investigation phraseology in his speeches on June 20, 21, 27 and the newly discovered speech of July 23.

[9] Bruce Frohnen, The Anti-Federalists: Selected Writings and Speeches (Regency House, 1999), 372.

[10] Cecelia M. Kenyon, The Antifederalists (The Bobbs – Merrill Co., 1966), 323.

[11] Morton Borden, The Antifederalist Papers (Michigan State University, 1965), 42, 180.

[12] Pauline Maier, Ratification: The People Debate the Constitution, 1787-1788 (Simon & Schuster, 2010), 83.

[13] William Kent, Memoirs and Letters of James Kent, LLD (Little, Brown & Co., 1898), 304-6.

[14] Ron Chernow, Alexander Hamilton (Penguin Books, 2004), 263.

[15] David J. Siemers, The Antifederalists: Men of Great Faith and Forbearance (Rowman & Littlefield, 2003), 138.

[16] Melancton Smith to Nathan Dane, 28 June 1788; DHRC, 22:2015.

[17] Perhaps the mashup “Brulancton” will catch on as the portmanteau for the “Brutus – Melancton Smith Authorship Thesis.”

[18] As pointed out in Part 2, during the ratification debate pseudonymous essays were intended to be shared, quotedand republished. The fact that an Antifederalist speech quoted from Brutus merely demonstrates that the delegate agreed with Brutus. For purposes of simplicity, attribution evidence prior to the publication of the Brutus essays will be referred to as “pre-authorship” evidence. By contrast, “post-authorship” evidence is properly viewed with healthy skepticism as the lifting of passages from pseudonymous essays by a convention delegate only demonstrates affinity, not authorship.

[19] DHRC, 22:1712.

[20] DHRC, 20:655.

[21] Brutus 10 argued that even if standing armies might be necessary on the frontiers or in times of emergency, this did not mean that the federal government “ought to be invested with power to raise and keep up a standing army in time of peace, without restraint; at their discretion.” DHRC, 20:655.

[22] Brutus 4 warned about individuals who were “artful and designing, and frequently possess brilliant talents and abilities; they commonly act in concert, and agree to share the spoils of their country among them; they will keep their object ever in view, and follow it with constancy.” Brutus 15 predicted that “the same gentlemen who have employed their talents and abilities with such success to influence the public mind to adopt this plan, will employ the same to persuade the people, that it will be for their good to abolish the state governments as useless and burdensome.” In a newly transcribed convention speech, Smith observed on June 30 that “the hon[orable] delegate from New York in particular, who has so elaborately on two successive days argued in favour of the Clause has talents capable of reasoning plausibly on either side of any political question…But still no reasoning Can change the nature of things or make truth falsehood.”

[23] Four examples of this fingerprint are set forth below:

- Brutus 3: “but if the clause, which provides for this branch, be stripped of its ambiguity, it will be found that there is really no equality of representation, even in this house.”

- Brutus 10: “striped of abundant verbages with which the author has dressed it”

- Plebeian: “The whole of what he says on that head, stripped of its artificial colouring, amounts to this, that the existing system is rather recommendatory than coercive, or that Congress have not, in most cases, the power of enforcing their own resolves.”

- June 21 convention speech: “Every man who will think for himself, will weigh the arguments offered on both sides, and judge for himself—He will strip them of the verbage with which they are clothed and seperate them from the artful specious forms they may assume”

[24] DHRC, 19:410.

[25] Smith used the word “therefore” in convention speeches on June 20, June 21, June 23, June 24, June 25, June 26, June 27, June 30, July 1 and July 2. Admittedly, many of the other delegates also routinely used the word “therefore” during the convention debates.

[26] In this chart, the “frequency” identifies the number of times the word “therefore” is used divided by the total number of words in the Brutus essays. In this example, Brutus used the word “therefore” 82 times, divided by 44,134 total words, equals a frequency of .186%.

[27] Brutus 16 contemplated that it would be followed by a future 17th essay. It appears, however, that Brutus’s efforts were redirected into the Plebeian pamphlet.

[28] This result is derived by dividing the number 10 by the number of Brutus essays.

[29] In Smith’s recently transcribed notes from 30 June 1788, he uses the word “maxim” twice. As will be described in Part 5, Smith’s handwritten notes are particularly valuable as transcriptions by third parties are arguably less precise to the extent that they aren’t always verbatim.

[30] Smith’s personal notes from 30 June 1788 were recently transcribed and will be available in the electronic edition of the DHRC.

[31] In formal logical reasoning, an argument is “valid” when the conclusion is guaranteed to be true if the premises are true. In other words, the conclusion flows logically from the premises of a valid argument.

[32] The frequency of Plebeian’s usage of the word “evident” / “evidently” is .042% of all words, which is comparable to Brutus (.048%), Federal Farmer (.037%) and Publius (.046%).

[33] Brutus also repeatedly used the word “reason” / “reasons,” including the following examples: Brutus 6: “immutable laws of God and reason”; Brutus 16: “an evident dictate of reason”; Plebeian: “the opposers of the constitution have reason on their side.”

[34] As previously indicated, the use of the word reasoning during the convention debates was widespread by Federalists and Antifederalists alike.

[35] Linda Grant De Pauw, The Eleventh Pillar: New York and the Federal Convention (Cornell University Press, 1966), 199.

[36] Noah Webster, A Compendious Dictionary of the English language (New Haven: Sidney’s Press, 1806), 2.

[37] Of course, nothing prevented pseudonymous essayists from conferring with convention delegates. This exercise would likely be easier for Federalists, as only a handful of convention delegates became Antifederalists: Elbridge Gerry (MA), Robert Yates (NY), John Lansing, Jr. (NY), George Mason (VA), Luther Martin (MD), and John Mercer (MD).

[38] Gordon S. Wood, “The Authorship of the Letters from the Federal Farmer,” WMQ, 3rd ser. 31 (1974), 299–308.

[39] John P. Kaminski, “The Role of Newspapers in New York’s Debate Over the Federal Constitution,” in Stephen L. Schechter and Richard B. Bernstein, eds., New York and the Union (Albany, 1990), 287.

[40] For example, Madison’s notes on July 7 recount that: “Mr. Gerry was for increasing the number beyond 65. The larger the number the less the danger of their being corrupted. The people are accustomed to & fond of a numerous representation, and will consider their rights as better secured by it. The danger of excess in the number may be guarded agst. by fixing a point within which the number shall always be kept.” Farrand, 1:569.

[41] Farrand, 2:644.

[42] DHRC, 4:xliv.

[43] Farrand, 3:588, 590.

[44] Paul H. Smith, Letters of Delegates to Congress (Library of Congress, 1995), 22:xxiv.

[45] Smith, Letters of Delegates to Congress, 5:xviii.

[46] Smith, Letters of Delegates to Congress (Library of Congress, 1995), 17:xx.

[47] Admittedly, Brutus does mention Congressional history dating back “as early as February 1781.” Yet, he arguably only reflects passing knowledge of the proposed Impost of 1781 compared to his more detailed knowledge of subsequent events.

[48] As described in the DHRC, on 1 November 1784 the Massachusetts legislature instructed its congressional delegation “to oppose, and by all ways and means to prevent the raising of a standing army of any number, on any pretence whatever, in time of peace.” DHRC, 20:622, n. 8. Smith would have been governed by this direction when he joined Congress in March of 1785. Elbridge Gerry was a leading opponent of standing armies, as discussed in Federal Farmer – Part 5. Richard H. Kohn, Eagle and Sword: The Federalists and the Creation of the Military Establishment in America, 1783–1802 (New York and London, 1975), 61.

[49] DHRC, 20:621.

[50] John P. Kaminski, George Clinton: Yeoman Politician of the New Republic (Madison House, 1993), 93.

[51] Kaminski, George Clinton, 93; DHRC, 19:xxxvii-ix.

[52] Related and interchangeable phrases included “the plan offered,” “the proposed plan,” and “the plan submitted by the convention.”

[53] The chart measures the number of times that the word “plan” is used, but purposely omits the word “plans.”