Melancton Smith’s watershed speech

The “Brutus – Melancton Smith Authorship Thesis” (Part 5)

Adam P. Levinson, Esq. & John P. Kaminski, PhD

During the summer of 1788 the New York ratification convention witnessed a clash of titans. For six weeks Alexander Hamilton, the Federalist “champion,”[1] squared off against his “chief interlocutor,”[2] Antifederalist Melancton Smith. This “battle of giants”[3] was not merely a contest between Hamilton and Smith. New York’s convention also matched Publius against Brutus, arguably two of the most important essayists during the debate over the ratification of the Constitution.

While his identity has been disputed for decades, historians widely agree that Brutus was “the most formidable antagonist of the immortal Publius.”[4] When Alexander Hamilton decided to recruit John Jay and James Madison to write The Federalist in the fall of 1787 he was responding to the letters of Brutus.[5] Madison described Brutus as a “combatant” whose critique “strikes at the foundation” of the proposed Constitution “with considerable address & plausibility.”[6] In hindsight this makes perfect sense as Melancton Smith has been described as the “most cogent anti-Federalist of his state,” the “Patrick Henry of New York.”[7]

During the months leading into the New York ratification convention, Brutus skirmished pseudonymously with Publius in the New York newspapers.[8] In addition to writing the sixteen Brutus essays, Melancton Smith also wrote a highly influential pamphlet as A Plebeian.[9] Accordingly, when the New York convention assembled in Poughkeepsie, Smith (Brutus) was the most qualified spokesman to face off against his nemesis Hamilton (Publius). As set forth below, newly uncovered manuscripts help prove that Melancton Smith was Brutus.

The debate in the New York ratification convention was arguably the hardest fought struggle in any of the state ratification conventions that considered the newly proposed Constitution in 1787-1791.[10] In addition to being the longest lasting convention, New York produced the largest number of proposed amendments.[11] New York was also the only state to formally propose a second constitutional convention.[12] The New York ratification convention thus became one of “the finest examples of political debate in American history.”[13]

Overview of Brutus Attribution

This blog post concludes a multi-part series exploring Brutus’ identity. The “Brutus – Melancton Smith Authorship Thesis” argues that Brutus was Melancton Smith, Alexander Hamilton’s chief antagonist at the New York ratification convention. The “Brutus – Melancton Smith Authorship Thesis” is based on a detailed review of decades of correspondence, pamphlets, legislative history, records of the New York ratification convention, and recently uncovered speeches by Smith. Much of this work is made possible after the completion of the monumental forty-seven volumes of the Documentary History of the Ratification of the Constitution (DHRC).

Part 1 provided an overview of existing scholarship and a summary of new evidence compiled by Statutesandstories.com in collaboration with John P. Kaminski. Part 2 focused on pre-authorship attribution evidence arising prior to the printing of the Brutus essays from 18 October 1787 to 10 April 1788. Part 3 continued with a discussion of post-authorship attribution evidence primarily arising from Smith’s speeches at the New York ratification convention. Part 4 focused on Smith’s syllogistical reasoning style which aligns with Brutus. Part 5 below discusses newly uncovered convention speeches by Melancton Smith which further confirm Smith’s identity as Brutus. In particular, Smith’s recently uncovered 23 July speech offers a fascinating window into Smith’s thinking during a seminal moment in the ratification campaign.

In the spring of 2025, Statutesandstories.com released a related seven-part series about the authorship of the Antifederalist Federal Farmer. Historians have long recognized that Brutus and the Federal Farmer were two of the most important Antifederalist authors. For many years Federal Farmer was believed to have been Richard Henry Lee. In 1974, historian Gordon S. Wood challenged this longstanding attribution, but did not offer an alternative author. In 1988, John P. Kaminski argued that Elbridge Gerry was Federal Farmer.[14] Click here for a link to the Federal Farmer – Elbridge Gerry Authorship Thesis (“FEAT”) which surveys newly uncovered evidence that Gerry was in fact Federal Farmer. With Gerry confirmed as Federal Farmer, the field is cleared for Melancton Smith to be recognized as Brutus.

Significance of Smith’s pivot to support ratification on July 23, 1788

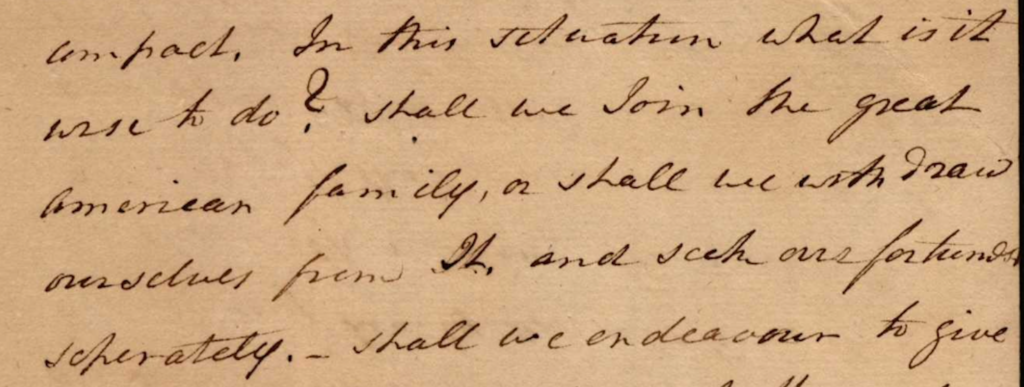

Antifederalists at the New York convention outnumbered Federalists by a margin of more than two to one.[15] Despite this overwhelming majority, near the end of the convention Smith pivoted to support unconditional ratification. In a stunning speech on 23 July 1788, which was no doubt one of the most dramatic moments of the convention, Smith announced the reasons for his change of heart. In beautifully written prose Smith asked whether New York will “Join the great American family,” or “shall we withdraw ourselves from It and seek our fortunes separately.” Smith answered that New York should take its place in the “family mansion” “with brotherly kindness and confidence,” relying on “common interests and common prudence” to obtain an improved Constitution.[16]

When Smith and his Antifederalist colleagues entered the New York convention they strenuously opposed ratifying what they considered a defective constitution unless it was accompanied by “conditional amendments.” Nevertheless, on July 23rd Smith advocated for ratification of the Constitution with “recommendatory amendments,” to be adopted through the Constitution’s amendment procedure in Article V. Although he pivoted to support unconditional ratification, Smith believed that “he was consistent in his principles and conduct.” In Smith’s mind, he was pursuing “his important and favourite object of amendments with equal zeal as before, but in a practicable way which was only in the mode prescribed by the Constitution.” For Smith, “amendments to the constitution were necessary” and it was “our duty to take the most Effectual and prudent means in our power to Obtain them.” Smith’s decision thus followed “equally the dictate of reason and of duty to quit his first ground, and advance so far as that they might be received into the Union.”[17]

Under Smith’s leadership, the Constitution was ratified by a razor thin vote of 30 – 27. Smith successfully convinced a dozen Antifederalists to support ratification “in full confidence” that recommended amendments would be considered in a second constitutional convention.[18] New York’s decision to join the union as the eleventh state was “arguably the nation’s most weighty vote in favor of ratification of the Constitution in 1787.”[19]

Although his role at the New York convention has largely been forgotten, Smith’s July 23rd convention speech is properly viewed as a watershed moment in American constitutional history:

Even though much of Melancton Smith’s life lies in obscurity, for a few days in July, 1788, he came as near as any man ever does to holding the fate of the nascent American nation in his hands. When he broke with most of his friends and political allies to support ratification of the Federal Constitution, he ensured New York’s adherence to the new Union and averted possible civil war, at the cost of his own political career.[20]

As explained by his biographer, Smith “performed an act of high statesmanship and of the greatest importance to the successful establishment of the new Union.”[21] Contemporary sources also recognized the importance of Smith’s pivot to support ratification:

I believe much praise is due M Smith, he found the improbability of having amendments made by the states previous to its becoming a government, & gave up his opinion to what he thought necessary for the tranquillity & advantage of the state. I do not think that he is any more convinced than when he left town. his conduct has been displeasing to many of the anti’s—his moderation & the abilities he has shown in convention has in some degree compensated with the federalists for his opposition.[22]

Henry Knox, the Confederation’s Secretary at War, praised Smith in a letter to George Washington. Knox explained the significance of Smith’s selfless vote which helped unify the nation:

Messrs Jay Hamilton and the rest of the federalists have derived great honor from their temperate and wise conduct during the tedious debates on this subject—nor ought those Gentlemen who were opposed to the constitution in the first instance, but afterwards voted for its adoption be deprived of their due share of praise for their candor and wisdom in assuming different conduct when it became apparent that a perseverance in opposition would most probably terminate in Civil War, for such and nothing short of it were the prospects.[23]

Knox’s concern over a possible civil war was not without foundation. Smith feared that New York City and the southern counties might secede from New York State if the Poughkeepsie convention rejected ratification.[24] Judged by historical standards, scholars have characterized the forbearance demonstrated by Smith and the moderate Antifederalists as “extraordinary for a group of revolutionaries.”[25] This blog post tells the story of the New York convention from Smith’s perspective using exciting, newly discovered manuscripts.

Newly discovered convention speeches

A handwritten manuscript of Smith’s speech of July 23 was recently discovered in the New York State Library in Albany. The speech was located in the files of an Antifederalist colleague, John Williams. Further complicating the historic record is the fact that the manuscript was not labeled or dated and does not appear to be in the handwriting of either Melancton Smith or John Williams.[26]

The manuscript of a second undated Melancton Smith speech was also recently discovered in Albany.[27] Believed to have been delivered on 11 July 1788, the second speech is consistent with Smith’s initial position that the New York convention should only ratify the Constitution with conditional amendments. By contrast, the July 23 speech reflects Smith’s shift to support unconditional ratification. The July 23 speech is thus significant as Smith justifies his controversial but vital support of unconditional ratification, with recommendatory amendments and a call for a second general convention.

Statutesandstories.com is also pleased to report that additional Melancton Smith files are now available to researchers for the first time.[28] Smith’s personal convention notes from June 30 and July 1 were recently transcribed by John P. Kaminski.[29] These newly published convention notes complement Smith’s July 11 and 23 speeches. Moreover, a compilation of proposed amendments and objections was also uncovered in the Melancton Smith Papers in Albany.[30] Taken together, this treasure trove of Smith materials represents over 13,000 words of historically significant text. As set forth below, these newly available primary sources help confirm Melancton Smith’s identify as Brutus.

Overview of the New York convention

The New York ratification convention began on June 17 with the Federalists heavily outnumbered. On June 24, news arrived in Poughkeepsie that New Hampshire had ratified the Constitution.[31] Although the Constitution had crossed the requisite nine-state ratification threshold, New York Antifederalists held their ground insisting on the need for conditional amendments. Shortly thereafter, Virginia unconditionally ratified with forty recommended amendments. To his credit, Smith realized that the ground had shifted. Smith’s July 23 speech announced his reluctant conversion away from conditional ratification. Comparing Smith’s July 11 and July 23 speeches enables scholars to examine the evolution in his thinking.

The New York convention learned on July 2 that Virigina had ratified the Constitution. The news was delivered by an express rider carrying a letter from James Madison to Alexander Hamilton.[32] While some Antifederalists insisted that nothing had changed, the Virginia ratification vote was in fact a “game changer.”[33] Prior to July 2, the Federalists “disputed every inch of ground” as the parties debated the Constitution from top to bottom, clause-by-clause. Beginning on July 3, the Federalists changed their strategy. “We now permit our opponents to go on with their objections and propose their amendments without interruption.”[34]

Although the news from Virginia didn’t alter the Antifederalists’ public position, the pace of the New York convention accelerated.[35] In early July the convention completed its section-by-section review of the Constitution and permitted the Antifederalists to exhaust “all of the amendments they could then think of.”[36] As described by Antifederalist Nathaniel Lawrence, “they have quietly suffered us to propose our amendments without a word in opposition.” Thereafter, the convention deadlocked.

Smith’s proposed off ramps and the “circular letter”

Despite the closely watched Virginia vote, New York Antifederalists continued to insist on conditional ratification. The parties were at loggerheads as the Federalists were only willing to agree to unconditional ratification, with recommended amendments. After the convention completed reviewing the Constitution by paragraph on July 7, the frustrated delegates dug in for a “week-long stalemate.”[37]

The Antifederalists privately caucused for two days over strategy. On July 10, John Lansing introduced the Antifederalist plan of conditional ratification. Described by historians as a “confusing array of more than fifty possible amendments,”[38] Lansing’s complex proposal envisioned three categories of amendments: explanatory, conditional and recommendatory. Federalists attacked Lansing’s proposal as a “gilded rejection,” which Congress was unwilling to accept.[39]

An informal committee with equal numbers of both parties was appointed on July 10, but failed to break the deadlock.[40] After reporting that “no plan of conciliation had been formed” by the committee, on July 11 John Jay offered the Federalist counterproposal. Jay moved that the Convention ratify without conditions, but with explanations and recommendatory amendments. The convention faced a “perfect crisis, with two opposing proposals on the table, each rigidly supported by one party or the other.”[41]

It was at around this time that Smith delivered his newly discovered speech of July 11. Smith indicated that it was “needless at this time” to repeat their arguments, as the constitution had been “sufficiently discussed—every member has had a fair opportunity to make up his mind on the subject.” Smith explained that “I have made up my own, and my opinion is, that if it is not greatly amended, that we have during the late revolution been fighting for a shadow.” Smith defended the Antifederalist position advanced by Lansing, involving three types of amendments. Smith described the advantages of the Antifederalist plan: it would “admit us into the union,” protect against “encroachments” by the federal government, and secure the “freedom of elections.” Smith concluded his July 11 speech by summarizing that the Antifederalist proposal “blends together the blessings of union and liberty.”[42]

As the Antifederalist floor manager, Smith faced a dilemma. In his private correspondence with Massachusetts Antifederalist Nathan Dane, Smith admitted his fear that there would not be “a sufficient degree of moderation in some of our most influential men, calmly to consider the circumstances in which we are, and to accommodate our decisions to those circumstances.” Wrestling with his “arduous and disagreeable” task, Smith confided to Dane that he wished to support his Antifederalist colleagues “as far as is consistent with propriety.”[43] Recognizing that “pride, passion and interested motives have great influence in all public bodies,” Smith predicted that “time and patience is necessary to bring our party to accord, which I ardently wish.”[44]

Smith planned – when the time was right – to offer “conditions subsequent” in place of “previous conditional amendments.” For Smith, his proposed conditions subsequent would “take place in one or two years after adoption or the ratification [would] become void.” By making this accommodation, Smith hoped to obtain his primary goal of “substantial amendments” rather than conditional ratification with unimportant amendments.[45]

Smith no doubt understood the implications of ratification by New Hampshire and Virginia. The “ground of argument” was now very different as the new constitution was no longer theoretical. Distinguishing between “then” and “now,” the New York Packet observed that “before” nine states had ratified there was hope of procuring amendments before its operation. “Now,” all hope of antecedent amendments had vanished. “Then,” the old Confederation was “entire and unimpaired.” “Now,” the new Constitution was in fact a reality and any non-ratifying states were on their own. “Then, those who voted against the New Constitution, only preferred the old one, or a chance for another: – Now, those who vote against the New Constitution, vote themselves out of the New Federal Union.”[46]

On Monday, July 14 impatient Antifederalist William Harper called for a vote, asserting that they had “spent three days doing nothing but talk” about competing proposals.[47] Hamilton sought to delay a substantive vote since “he supposed it would amount to a rejection.”[48] As described by Federalist David Bogart, “[t]he important decisive question would have been put this morning, had not the eloquent Hamilton and Mr. Jay pleaded the postponement (at least till tomorrow), of a question the most serious and interesting ever known to the people of America.”[49]

Instead of a vote, July 15 brought a “flurry” of competing motions.[50] Smith and Hamilton offered dozens of proposed amendments intended to break the deadlock. Smith moved for ratification “but disallowance of certain provisions from taking effect until a second convention met to consider amendments.” Under Smith’s proposal, ratification would be conditioned upon Congress only exercising limited power over: 1) federal elections, 2) deployment of the militia outside NY, and 3) the levying of direct taxes.[51] In other words, Smith’s July 15 motion might be described as “limited ratification,” compared to Lansing’s “conditional ratification” and Jay’s “unconditional ratification.”[52]

On July 16 the Federalists feared the outcome of a pending vote. Recognizing that adjournment would be preferable to defeat, Federalist delegate John Sloss Hobart moved for adjournment until September.[53] James Duane, the Federalist mayor of New York City, seconded Hobart’s motion. For the next two days the delegates debated the implications of adjournment, which was temporarily postponed until July 17.[54]

On July 17 the increasingly frustrated delegates had been deliberating at the convention for a month. By a vote of 40 to 22, the Antifederalists rejected the Federalist motion to adjourn until September. Recognizing that time was running out, Smith decided to take the “disagreeable” and controversial steps outlined in his correspondence with Dane. According to Michael Klarman, Smith “stunned the delegates by taking another step in the Federalist’s direction” and abandoned his support for Lansing’s proposal.[55] Historian Pauline Maier describes the fateful moment when Smith began his pivot:

For a moment the agenda seems clear. The convention would turn next to Smith’s [earlier] motion…But then, in one of the strangest turns in that most complex convention, Smith announced that he no longer supported his own proposal because he had come to think that Congress would not accept it.[56]

Smith courageously explained that he originally believed that Congress would accept the conditional mode of adoption he had previously proposed, but he was “mistaken.” He wished therefore to “withdraw” his prior motion, as there was “little reason to expect that we shall be received on these terms.” He freely admitted that he stood on “ticklish ground.” Smith expected that his position would “not please either side of the house.” Smith explained that he shifted his ground to occupy a “better position” that would “secure an admission into the union & procure a consideration of amendments.”[57]

In an effort to engineer a compromise Smith offered a substitute proposal.[58] Smith began with a list of seven categories of defects in the Constitution – which all aligned with the arguments Brutus had been making since October of 1787. A detailed spreadsheet comparing Smith’s July 17 motion with Brutus is available upon request. Smith explained that based on these objections the convention would not have acceded to the Constitution, but for “the strong attachments they feel to their sister States, and their regard to the common good of the Union, impel them to preserve it.”[59]

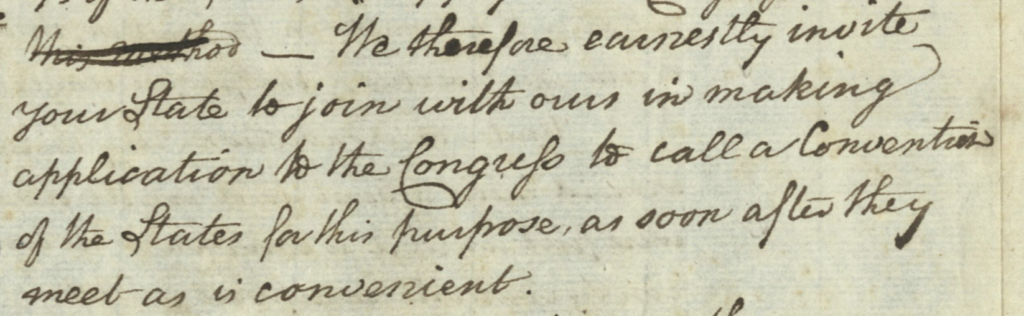

Smith’s detailed motion included an escape clause. Smith proposed that New York should ratify with the stipulation that it could “recede and withdraw” from the union if Congress did not call for a second convention.[60] Smith also moved “that a circular letter be addressed to all the States in the Union” enclosing proposed amendments, and “earnestly inviting them to join with this Convention in requesting the Congress at their first meeting, to call a Convention of the States, to consider of the amendments proposed by all the States.”[61]

Antifederalists received Smith’s proposal with “indignation & suspicion.”[62] Although Smith presented his July 17 motion “from the sincerest desire to accommodate,” it split the Antifederalist ranks. Smith’s proposal was met with “a long silence,” forcing the Antifederalists to privately caucus on July 18 and 19. As reported by one observer, some of Smith’s colleagues were “enraged” by his proposal and “detest Smith as much as Hamilton.”[63]

Despite the schisms he was creating among his Antifederalist colleagues, Smith was appointed to an informal working committee. Two Antifederalists and two Federalists were charged with “arranging the amendments agreed to” and “other matters not considered.”[64] While the delegates might agree on proposed amendments, the looming question was the unresolved “form” of ratification. Federalist delegate Isaac Roosevelt observed that the convention was divided into four classes: 1) ratification with conditions, 2) ratification with a right to withdraw if a second convention wasn’t obtained, 3) absolute ratification, and 4) adjournment.[65]

Smith had still more ground to traverse. When they entered the convention Smith and the Antifederalists wanted conditional ratification. On July 15 Smith had proposed limited ratification. On July 17 he shifted to ratification “on the express condition” that a second convention meet “as soon as possible” to consider amendments.”[66] Smith now sought to walk his fellow delegates away from his proposed condition subsequent to unconditional ratification.

In addition to Roosevelt’s four camps, the range of possible approaches included the following: 1) conditional ratification with conditions precedent [Lansing on July 10], 2) unconditional ratification [Jay on July 1], 3) limited ratification constraining objectionable Congressional powers [Smith on July 15], 4) temporary adjournment [Hobart on July 17], 5) ratification with the right to withdraw based on a condition subsequent [Smith on July 17], and 6) rejection. Ultimately, New York approved unconditional ratification with a detailed set of proposed, non-binding amendments and a circular letter calling for a second general convention.

As described in Smith’s July 23 speech, New York should propose, not dictate terms to the ratifying states. Smith asked:

Shall we endeavour to give the laws to the other parts of It, and dictate to them the terms of our Admission or shall we with brotherly kindness and confidence take our station in the family transition, and rely on common interest and common prudence for those Alterations and improvements which in our opinion will be calculated to render It more commodious and safe—?

The decisive vote for ratification would be taken on July 23, the day that the informal committee of four reported its recommended amendments.[67] Antifederalist Samuel Jones, supported by Smith, suggested unconditional ratification with wordsmithing. Jones moved to substitute the words “in full confidence” that amendments would be adopted, in place of the phrase “upon condition.” The critical vote was 31 to 29, with twelve Antifederalists crossing party lines to vote with the Federalists. Based on the resulting compromise, an extensive list of non-binding amendments would be recommended, accompanied with Smith’s concept of a circular letter to the states proposing a second convention.

The New York Circular Letter

On July 26, the Federalists acquiesced in a final Antifederalist demand. A three-member committee consisting of John Jay, John Lansing and Smith was appointed to draft a “circular letter” to the states recommending, but not insisting on a second general convention of the states to consider proposed amendments.[68] The New York convention adjourned after unanimously approving the circular letter. Both Smith and Jay prepared their own drafts.[69] As described below, Smith’s draft of the circular letter aligns with Smith’s July 23 speech and contains fingerprints which provide further evidence of the “Brutus – Melancton Smith Authorship Thesis.”

The New York circular letter was a “remarkable document.”[70] While multiple states including New York proposed amendments, New York was the only state that endorsed a second general convention by circulating a formal letter to its “sister states.” The so-called “circular letter” was signed by New York’s governor George Clinton as the President of the New York ratification convention and addressed to the chief executives of the other twelve states. The circular letter was the means by which New York invited the other states to join its call for a second convention.[71] Circular letters seeking collective state action had been used for various purposes during and after the revolutionary war.[72] Not surprisingly, the idea for a New York circular letter was initially proposed by Melancton Smith.[73]

Alignment of the recently discovered manuscript of Smith’s July 23 speech and the broadside report of Smith’s July 23 speech

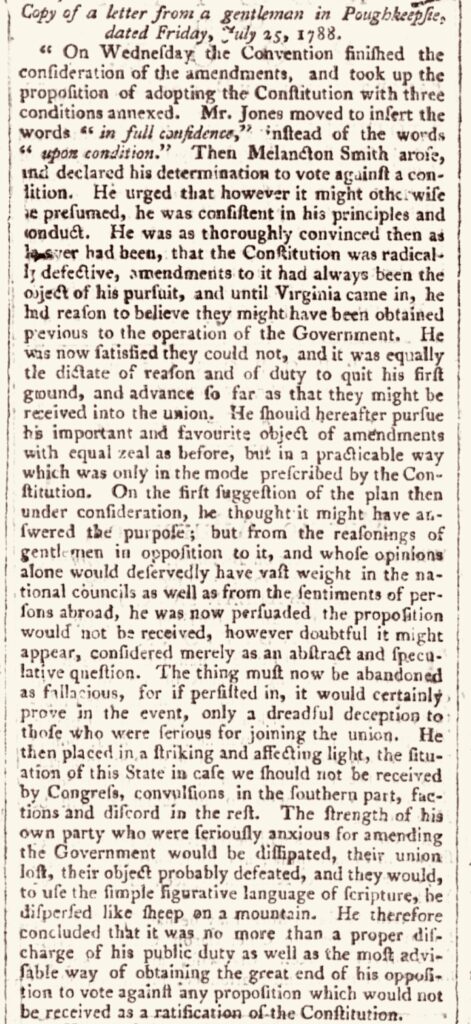

The recent discovery of Smith’s historic July 23 speech evidences Smith’s full pivot to unconditional ratification. While detailed transcriptions of the convention debates were kept in June, records are sparse for July. For example, newspaper publisher Francis Childs stopped taking daily shorthand notes after July 2.[74] Until now, the best account of Smith’s July 23 speech was a special edition, “Supplemental Extraordinary,” report in the New York Independent Journal.[75] Published by John and Archibald M’Lean on July 28, the folio-sized broadside report contained a detailed summary of Smith’s July 23 speech (hereinafter the “broadside report”). Recognizing the importance of Smith’s decisive speech, the Independent Journal reported that it was being summarized “with fidelity” and as nearly as possible in Smith’s “own language”:

I have been rather particular in stating the business of Wednesday to you, because I think it is of a decisive nature; and I was so well pleased with Smith’s speech, that I have given you the substance of it with fidelity, and nearly as I could in his own language.…”[76]

Based on the content of the manuscript discovered in Albany there should be no doubt that it was Smith’s critical July 23 speech. Although the Albany manuscript is not labeled or dated, it aligns with the Independent Journal’s summary of Smith’s July 23 speech.[77] The following chart compares the newly discovered manuscript with the broadside report in the Independent Journal:

| Broadside report of July 23 speech | Manuscript of July 23 speech |

| “Melancton Smith arose, and declared his determination to vote against a condition.” | “I was once, Mr Chairman a friend to conditional Amendments but after the most mature consideration and expecting upon reflecting seriously on the present state of the question, I am induced to think that they ought not to be persisted in, in any shape.” |

| “He urged that however it might otherwise be presumed, he was consistent in his principles and conduct.” | “As my anxiety to have amendments made is well known[.] my motives cannot be mistaken. I am persuaded firmly in my own mind that our amendments should be recommendatory, and that If we annex conditions to them we shall depart far from that line of prudence and propriety, which all the other objecting states without exception have concurred in observing.” |

| “He was as thoroughly convinced then as he ever had been, that the Constitution was radically defective, amendments to it had always been the object of his pursuit…” | “Many are the difficulties which will and must attend the plan of previous conditional amendments, and the more we examine and investigate the nature and tendency of such a measure, the more I become Convinced that It will operate to defeat the very purposes which we wish so ardently wish to Attain” |

| “it was equally the dictate of reason and of duty to quit his first ground, and advance so far as that they might be received into the Union.” | “It is our duty to take the most Effectual and prudent means in our power to Obtain them.—the only question then is, what those most Effectual and prudent means are” “If we give our amendments the form of conditions, I fear we shall put ourselves on higher ground than we can maintain…” |

| “from the reasonings of gentlemen in opposition to it, and whose opinions alone would deservedly have vast weight in the national councils as well as from the sentiments of persons abroad, he was now persuaded the proposition would not be received” | “As It is I cannot help wishing for amendments. Yet I confess that when I consider how many wise good men, men who have given the fullest evidence of their love of their country, have either been concerned in framing or have since [missing lines]” |

| “He then placed in a striking and affecting light, the situation of this State in case we should not be received by Congress, convulsions in the northern part, factions and discord in the rest. “ | “A dismemberment of the state however grating or unwelcome the supposition may be seems to be a probable consequence. If It should be thought of, can we prevent It—Besides the strength of the seceeding part itself what efforts can be looked for from the divided and disagreeing residue of the state in offensive operations.” “Disunion on the contrary will not only beget weakness and of Course insecurity against foreign dangers but will occasion strifes and quarrels among ourselves and while It exposes us to all the horrors of internal war…” |

| “He therefore concluded that it was no more than a proper discharge of his public duty as well as the most advisable way of obtaining the great end of his opposition to vote against any proposition which would not be received as a ratification of the Constitution.” | “I cannot help concluding that a conditional adoption is a rejection—It seems to me to amount to this—we reject the thing proposed and we propose instead of It something else—Congress cannot Know us but thro the constitution, If we agree to that we are of course received into the union—If we do not agree to It or which is I conceive the same thing—If we agree to it upon condition that It must be altered and made a different thing, we then cannot be received into the union…” |

Smith’s July 23 speech aligns with his draft of the Circular Letter

The phraseology of the July 23 speech also aligns with Smith’s draft of the convention’s circular letter. Importantly, Smith’s July 23 speech would likely have been fresh in his mind when he drafted the circular letter. While it is unclear when Smith began preparing his draft of the circular letter, he proposed the concept of the circular letter on July 17. The convention voted to appoint a committee of Smith, Lansing and Jay to prepare the circular letter on July 25.[78]

The following chart compares the newly discovered manuscript of Smith’s July 23 speech with Smith’s draft of the circular letter:

| July 23 speech | Smith’s circular letter draft |

| “our sister states” (2x) | “our sister states” |

| “calling a General Convention” | “calling another general Convention” |

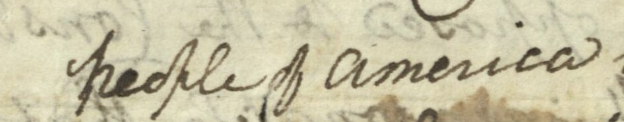

| “the people of America” | “the people of America” |

| “join with us in promoting them” “Shall we Join the great American family” |

“they will join with us” “join with ours” |

| “the constitution in the present form” | “the constitution in the present form” |

| “at the expensive of so much blood and treasure” | “a vast expence of blood & treasures” |

| “such occasions” | “such an occasion” |

| “the operation of the System” | “the operation of the Government” “going into operation” |

| upon what terms we will accede | “our sister States have already acceded to the system” “therefore acceded to the Constitution” |

| sentiments (2x) | sentiments (3x) |

| defects (3x) | defects (2x) |

| “shall increase the common interests of the people of America in the common liberty, and are well know[n] that they have shown as strong an attachment to it as we have” | “We beleive their attachments to Liberty is equally strong with ours” attachment (3x) |

| “every well grounded clause of Apprehension” “What have we not to apprehend from such a situation?” |

“secure and quiet those apprehensions” “They are entitled to a security for them, and even to have their apprehensions of danger removed” |

| union (8x) | union (3x) |

| “I am induced to think” | “the reasons which induce us to disapprove” “sufficient to induce a reconsideration of it” |

| “line of prudence and propriety” “can never hesitate about the propriety of calling a convention” “strong argument in the public mind of the propriety of a thing” |

“we cheerfully consent to submit to their determinations on the propriety of the amendments to be made to this system” |

| disposition (3x) | “men in whose ability & dispositions” |

| “necessary to the prosperity of the farm” | “essential to the public prosperity safety and happiness” |

| “calculated to render It” | “as will render those invaluable rights and Liberties” |

| “in the national council” “Joint councils and of the Major voice” “council the leaders” |

“united councils of the people” |

| “previous conditional amendments” (2x) | “amendments previous to” |

| “Shall we in order to secure liberty” “security of liberty” |

“in order to secure the Liberties of the people” “as will secure the Liberties of the people” |

| confidence (4x) | “fullest confidence”; “fullest confidence”, “highest confidence” |

| “manifest confidence” | “We trust the amendments we have proposed will manifest that none of our objections have originated from those sources” |

| sense (4x) | “our sense of its defects” |

| “never submit to be taxed” “consent to submit ours to the general voice” “can ever submit to such treatment” |

“submit to their determination” |

| decisive step | decisive proof |

| “power which I fear may prove dangerous” “I fear we shall put ourselves” “I fear may be attended” |

“their fears should be quieted,” |

| “The greatest proportion of the inhabitants” “A respectable proportion of the citizens” |

“a great proportion of the people” |

| “large majorities” | “a large majority” |

| “is this a reasonable reliance” | “It is reasonable that their fears should be quieted” |

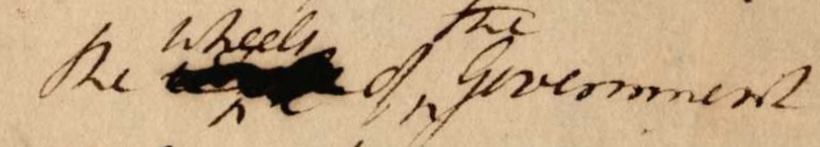

| “an essential step to putting the wheels of the Government in motion” | “essential to the public prosperity safety” |

| “procure a more ample vent” | “procure amendments” |

| “to contend with” | “so nobly contended” |

| “or shall we withdraw ourselves from it” | “withdraw from it” |

| “we are not to presume” | “it is to be presumed” “we presume” |

Alignment between Smith’s newly discovered July 23 speech and Nathan Dane’s letter of July 3

Particularly useful attribution evidence connecting Melancton Smith and the newly discovered July 23 speech can be found in Nathan Dane’s letter of July 3. Among other things, Dane explained that the “situation” of our government was “a matter of common concern” after New Hampshire and Virginia had ratified. As a result, “the Constitution is already established there can be no previous amendments.” Dane was also concerned about possible violence, warning that our people, though enlightened are “high spirited.” On July 15, Smith wrote back to Dane indicating that “I entirely accord with you in Opinion and shall if necessary avow them—Time and patience is necessary to bring our party to accord, which I ardently wish.”[79] To the extent that Smith’s July 23 speech was the pivotal moment when he did so, it should not be a surprise that Smith’s July 23 speech aligns with Dane’s July 3 letter.

The following chart compares the newly discovered manuscript of Smith’s July 23 speech with Dane’s July 3 letter:

| Dane’s July 3 letter | Smith’s July 23 speech |

| “our people tho enlightened are high spirited“ | “the other states, who are as free as independent and as high spirited as we are” |

| “a matter of common concern“; “common interest“ | “rely on common interest and common prudence;” “Will they be inclined to make common cause with us;” “If we go into the operation of the System we shall have a voice in the event and shall increase the common interests of the people of America in the common liberty” |

| “the State that adopts this mode comes into the Union armed with the declared Sentiments of her people, and will immediately have a voice in the federal Councils… whereas if she adopts conditionally She will not have a voice in those Councils“ | “It hath always been held right and proper that all measures touching the public weal should be the result of Joint councils and of the Major voice.”

“And we ought to be content to submit ours to the General voice, and not demand that the General voice shall declare that to be good which the General Judgment may think imperfect” |

| “It cannot be proper for any State positively to say to the others, that unless they precisely agree to the alterations she proposes she will not accede to the Union—this would be rather dictating” | “Shall we endeavour to give the laws to the other parts of It, and dictate to them the terms of our Admission”. “In private life we think it assuming and Indelicate for any man to dictate to his neighbours…”

“They propose but they do not dictate[.] They recommend but they do not impose;” |

| “the State that adopts this mode comes into the Union armed with the declared Sentiments of her people…” | “the most powerful and influential States concur with us in thinking that certain defects in the constitution ought to be remedied—they have declared other sentiments “ |

| “Our object is to improve the plan proposed: to Strengthen and secure its democratic features; to add checks and guards to it; to secure equal liberty” | “Shall we in order to secure liberty, dissolve our ties” |

| situation (5x) | situation (6x) |

| “probable consequence of any hostile beginnings” “the probable consequence of either beginning” | “A dismemberment of the state however grating or unwelcome the supposition may be seems to be a probable consequence.” |

| “we cannot reasonably expect“ | “we cannot reasonably expect” “we may reasonably expect“ |

| “Even when a few states had adopted without any alterations, the ground was materially changed; and now it is totally shifted” | “If we give our amendments the form of conditions, I fear we shall put ourselves on higher ground than we can maintain…” |

| “merely because she does not accede to a national compact”

“unless they precisely agree to the alterations she proposes she will not accede to the Union” |

“If the first, upon what terms we will accede to this new and momentous compact.” |

Alignment between Brutus and newly discovered Smith manuscripts and speeches

During the course of the convention, Melancton Smith’s public position shifted as the situation and circumstances on the ground changed. Nevertheless, certain signature words and phrases repeat in his newly discovered speeches. Many of these words and phrases used by Melancton Smith can be characterized as Brutus fingerprints.

The Brutus Part 3 blog identified the frequent use of biblical references as a signature Melancton Smith fingerprint. The Broadside report of Smith’s July 23 speech is a perfect example. Smith explained that he feared that if New York refused to join the union the strength of the Antifederalist party would be “dissipated, their Union lost, their object probably defeated, and they would, to use the simple figurative language of Scripture, be dispersed like sheep on a mountain.”[80]

The recently discovered manuscripts of Smith’s July 11 and July 23 speeches similarly contain biblical allusions. Unlike many other founders, Smith did not have a classical college education. Nevertheless, he was well versed in biblical texts. He invoked Job 38:11 in his July 23 speech by indicating that “we are not to presume that all the other states will agree that the Constitution ought to be altered Just so far and no further than” the state of New York might dictate.[81]

As described in Brutus Part 3, Smith’s religiosity dates back decades. In a letter from Smith to his friend Henry Livingston in 1771, Smith invoked the blessings of heaven three times: “May the smiles of a kind and indulgent Heaven cheer you”; “may Heaven grant”; “Heaven bless you.” These blessings/references to heaven align with Smith’s convention speeches (on June 20, 25, 27), five of Brutus’s letters (Brutus 1, 5, 7, 10, 15) and Plebeian.

For example, Brutus 1 describes the debate over the constitution as follows:

The most important question that was ever proposed to your decision, or to the decision of any people under heaven, is before you, and you are to decide upon it by men of your own election, chosen specially for this purpose. If the constitution, offered to your acceptance, be a wise one, calculated to preserve the invaluable blessings of liberty, to secure the inestimable rights of mankind, and promote human happiness, then, if you accept it, you will lay a lasting foundation of happiness for millions yet unborn; generations to come will rise up and call you blessed.

Smith’s July 11 speech summarized that the Antifederalist plan of conditional amendments he was proposing “blends together the blessings of union and liberty.” Smith’s draft of the circular letter similarly referred to “the blessing” of liberty, which was earned “by a vast expence of blood & treasures.” Smith’s July 23 speech likewise used the phrase, “so much blood and treasure” as does Brutus 10 “more blood and treasure.”

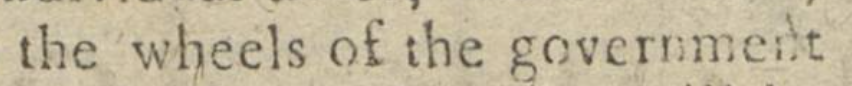

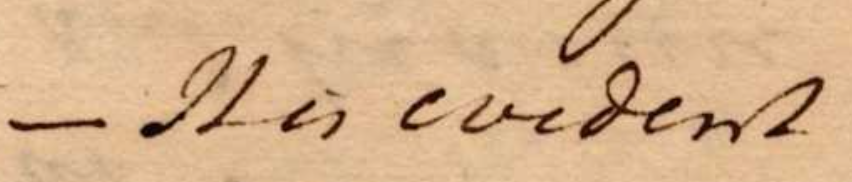

Smith’s July 23 speech also aligns with Brutus 1. The phrase “the wheels of the government” appears a total of two times in the Documentary History of the Ratification of the Constitution. Brutus 1 used the phrase on 18 October 1787 and the phrase is also used in an essay in the Boston Gazette on 3 December 1787.[82]

In his newly uncovered July 23 speech, Smith explained that:

“I cannot agree with Gentlemen who may think that we ought to risk every thing in the endeavours to obtain Amendments. —I think we shall have sufficient security in different states….Congress can never hesitate about the propriety of calling a convention[.] This will be an essential step to putting the wheels of the Government in motion, and from that convention we may reasonably expect a removal of every well grounded clause of Apprehension.”

Another example of alignment with Brutus and the newly uncovered Melancton Smith speeches involves the concern that decisions be prudent. For example, the second sentence of Brutus 1 expresses his goal “to lead the minds of the people to a wise and prudent determination….” Similarly, the first sentence of the July 11 speech indicates that “[w]e ought not Vote to agree implicitly to a form of govt. which will diminish or destroy it. Events may nevertheless turn up which make it in some measure expedient and prudential to accede entirely to a form of govt. greatly defective.” Smith’s July 23 speech used the word prudent/prudence/propriety a total of seven times as follows:

- Effectual and prudent means in our power to Obtain them.—the only question then is, what those most Effectual and prudent means are

- rely on common interest and common prudence

- depart far from that line of prudence and propriety

- Congress can never hesitate about the propriety of calling a convention

- a strong argument in the public mind of the propriety of a thing

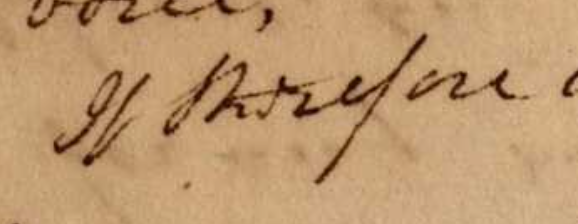

The Brutus Part 4 blog post examines Brutus’ syllogistical reasoning style which aligns with Smith’s speeches and correspondence. It should thus be no surprise that the following pattern continues in Smith’s July 23 speech:

- observation/observing (2x)

- evident/evidence (4x)

- therefore (3x)

- hence (2x)

Additional examples of alignment between Smith’s newly uncovered speeches and Brutus are set forth in the chart below:

|

Phrase/Fingerprint |

Smith speech or Brutus essay |

| “people of America” | July 23; Brutus 2, 3, 4, 9; Smith draft of circular letter; Plebian; June 21, July 17 |

| “our sister states” | July 23 speech; July 17 speech; Smith draft of circular letter; Plebeian |

| investigation/investigate | July 23 speech; Smith draft of circular letter; Brutus 1, 3, 6, 11, 14, 16 |

| “previous conditional amendments” | July 23; June 28 letter to Nathan Dane |

| “the history of the world” | July 23 speech; Plebeian |

| “the least reflection” | July 23 speech; Brutus 10, Plebeian |

| “nature and tendency” | July 23 speech; Brutus 13 |

| “proper principles” | July 23 speech; Brutus 4 |

| “Republican principles” | July 23, June 30, June 21 |

| compact | July 23 (“new and momentous compact”); Brutus 2 (“will be an original compact”); Brutus 5 (“intended as an original compact”); Brutus 12 (“will not be a compact entered into by the states, in their corporate capacities, but an agreement of the people”) Plebeian (“momentous question…secured by a solemn compact”) |

| “fancy” “fanciful” | July 11 speech; June 21 speech, July 2 speech |

| “tragic description and comic exhibitions” v. “comic talents…theatrical exhibitions” | July 11 speech; July 2 speech |

| “to alarm the fears of the people” v. “fear is a powerful and prevailing passion” | July 11 speech; Brutus 1 |

| shadow | July 11 (“fighting for a shadow”); Brutus 3 (“shadow of the right”), 4 (“shadow of representation”), 10 (“mere shadow without the substance”), June 21 (“mere shadow of representation”) |

| defect; defective | July 11; July 23; Brutus 1, Brutus 3, Brutus 14 |

| situation | July 11; July 23, Brutus 1, Brutus 10, Brutus 11, Brutus 13, Brutus 15, Brutus 16, June 20, June 27, Smith’s June 28 letter to Nathan Dane |

| circumstances | July 23 speech, June 21, June 27, Smith’s June 28 letter to Nathan Dane, June 30, July 1, July 17 |

Historians and scholars are invited to share their input on the “Brutus – Melancton Smith Authorship Thesis.” The authors are more than happy to answer any questions.

Endnotes

[1] Melancton Smith to Nathan Dane, 28 June 1788, DHRC, 22:2015.

[2] Emery G. Lee, III, “Representation, Virtue and Political Jealousy in the Brutus-Publius Dialogue,” The Journal of Politics, vol. 59, no. 4, 1073-95, 1075 (November, 1997).

[3] Zuckert & Webb, xi

[4] William Jeffrey, Jr. “The Letters of ‘Brutus’ – A Neglected Element in the Ratification Campaign of 1787-1788,” University of Cincinnati Law Review, vol. 40, no. 4., 643-663, 643 (1971).

[5] DHRC, 13:497, note 2. Another New York Antifederalist who might have prompted a response by Hamilton was Cato, which was first published on 27 September 1787 in the New York Journal. DHRC, 19:58.

[6] James Madison to Edmund Randolph, 21 Oct. 1787, DHRC, 19:104

[7] Alfred F. Young, The Debate over the Constitution, 1787-1789 (Rand McNally & Co., 1965), 1.

[8] The first Brutus essay appeared in the New York Journal on 18 October 1787. Federalist No. 1 was published two weeks later in the New York Independent Journal on October 27. DHRC, 13:486.

[9] DHRC, 20:942.

[10] William Jeffrey, Jr. “The Letters of ‘Brutus’ – A Neglected Element in the Ratification Campaign of 1787-1788,” University of Cincinnati Law Review, vol. 40, no. 4., 643-663, 643 (1971).

[11] “The document approved by the New York convention in ratifying the Constitution was longer and, like the convention itself, more complicated than that of any other state.” Pauline Maier, The People Debate the Constitution: 1787-1788 (Simon & Schuster, 2010), 397.

[12] New York was also the only state to formally endorse a second general convention, calling on other states to take action. Kaminski, George Clinton, 166. The so-called “circular letter” unanimously approved by the New York ratification convention was sent to all state governors on 26 July 1788. DHMC, 23:2335.

[13] Zuckert & Webb, xii.

[14] John P. Kaminski, “The Role of Newspapers in New York’s Debate Over the Federal Constitution,” in Stephen L. Schechter and Richard B. Bernstein, eds., New York and the Union (Albany, 1990), 280–92. See also DHRC, 19:203.

[15] Of the 65 delegates elected to the convention, 46 were Antifederalists and 19 were Federalists. DHRC, 22:1669.

[16] https://rotunda-upress-virginia-edu.i.ezproxy.nypl.org/founders/RNCN-02-23-02-0001-0009-9001

[17] New York Independent Journal, 28 July 1788; DHRC, 23:2282.

[18] Antifederalist Samuel Jones moved to insert the words “in full confidence” in place of the phrase “upon condition.” Smith immediately endorsed Jones’ motion, which carried the day. DHRC, 22:1674.

[19] Zuckert & Webb, xi

[20] Brooks, ix.

[21] Brooks, 358.

[22] Seth Johnson to Andrew Craigie, 27 July 1788, DHRC, 23:2428.

[23] Henry Knox to George Washington, 28 July 1788. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/04-06-02-0370

[24] John Jay to George Washington, 29 May 1788; Alexander Hamilton to James Madison, 8 June 1788. DHRC, 20:1119, 1135.

[25] David J. Siemers, The Antifederalists: Men of Great Faith and Forbearance (Roman & Littlefield, 2003), 30.

[26] Smith, Melancton, “Speech in the New York Convention,” Wednesday, 23 July 1788, Papers of John Williams. Box 8, folder 30. New York State Library’s Manuscripts and Special Collections, Albany. https://rotunda-upress-virginia-edu.i.ezproxy.nypl.org/founders/RNCN-02-23-02-0001-0009-9001

[27] It is believed that the speech was delivered on July 11. The notes for the speech were found in the New York State Library, Papers of John Williams, Box 8, folder 36, in a “miscellaneous material” file. https://rotunda-upress-virginia-edu.i.ezproxy.nypl.org/founders/RNCN-02-22-02-0002-0024-9003

[28] https://www.statutesandstories.com/blog_html/breaking-news-melancton-smiths-speech-discovered-in-albany/

[29] Earlier this year, twenty-five pages of Melancton Smith’s personal notes of the debates in Poughkeepsie were transcribed and published for the first time. Smith’s convention notes had been held in private hands after being sold at auction at Sotheby’s in 2017. In addition to Smith’s notes for his speech of June 30, the manuscript also includes Smith’s notes of speeches by John Jay, Alexander Hamilton, and James Duane. DHRC, Digital Edition.

[30] DHRC, Digital Edition.

[31] DHRC, 22:xxv.

[32] DHRC, 21:1214; 21:1217.

[33] Melvin Yazawa, Contested Conventions: The Struggle to Establish the Constitution and Save the Union, 1787-1789 (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016), 183.

[34] Yazawa, 184. “[T]hey have quietly suffered us to propose our amendments without a word in opposition.”

[35] From June 20 through July 2, the convention exhaustively debated only eight sections of the Constitution (Article I, Section 1 though Article I, Section 8, paragraph 2).

[36] Yazawa 184.

[37] DHRC, 22:1672; Yazawa, 192.

[38] Yazawa, 185.

[39] DHRC, 22:1675.

[40] According to newspaper reports, the committee “dissolved without effecting anything.” DHRC, 22:2127.

[41] Maier, 381.

[42] An important theme of Smith’s July 11 speech was the preservation of the union and liberty. The speech uses the following phrases: “promote liberty and union;” “love of peace and union,” and “blessing of union and liberty.” DHRC, Digital Edition; https://rotunda-upress-virginia-edu.i.ezproxy.nypl.org/founders/RNCN-02-22-02-0002-0024-9003

[43] As discussed below, recognition of their changed “circumstances” and acting consistent with “propriety” are fingerprints in Smith’s correspondence with Dane, which reappear in Smith’s newly discovered speeches.

[44] Smith’s strategic thinking is outlined in a series of letters between Smith and Nathan Dane. Dane was a pragmatic Antifederalist from Massachusetts serving as a member of Congress in New York City. DHRC, 21:1254; 22:2015.

[45] DHRC, 21:1254; 22:2015.

[46] New York Packet, 15 July 1788; DHRC, 22:2163.

[47] DHRC, 23:2171. Maier, 386.

[48] DHRC, 23:2172.

[49] DHRC, 23:2175 (David S. Bogart to Samuel Blachley Webb, 14 July 1788).

[50] Maier, 386.

[51] Procedurally, Smith moved to amend Jay’s motion so that ratification would be conditional. Yazawa 191, Maier 386.

[52] DHRC, 23:xxix.

[53] John Sloss Hobart was a justice on the New York Supreme Court. The Federalists suggested that adjournment would enable the delegates to consult their constituents. Adjournment was also a means of delaying a vote which the Federalists feared would result in a de facto rejection of the Constitution. Maier, 387.

[54] DHRC, New York Supplement, 430.

[55] Michael J. Klarman, The Framers’ Coup: The Making of the United States Constitution (Oxford University Press, 2016), 503.

[56] Maier, 389.

[57] Yazawa, 192. DHRC, 23:2211-13.

[58] Yazawa 193; Maier 389.

[59] DHRC, 23:2213-2215.

[60] DHRC, 22:1673.

[61] DHRC, 23:2215.

[62] DHRC, 23:2190.

[63] DHRC, 23:2232.

[64] DHRC, 23:2254.

[65] Isaac Roosevelt was the great-great-grandfather of Franklin Delano Roosevelt. DHRC, 23:2375.

[66] DHRC, 23:2212.

[67] Klarman, 506.

[68] Siemers, 226. Jay’s draft also contains marginal notes by Alexander Hamilton. DHRC, 23:2339, n.1.

[69] DHRC, 23:2504.

[70] Kaminski, George Clinton, 166.

[71] DHRC, 37:153, editorial note.

[72] One of the most famous circular letters was George Washington’s June 1783 Letter to the Executives of the States. DHRC, 13:60. The Constitution was sent to Congress by the “Constitution’s cover letter,” a transmittal letter from George Washington as the President of the Constitutional Convention to Congress dated 17 September 1787. DHRC, 1:305. In turn Congress transmitted the Constitution to the states with a circular letter dated 28 September 1788. DHRC, 1:340.

[73] DHRC, 23:2215.

[74] DHRC, 19:lxix.

[75] DHRC, 23:2282.

[76] DHRC, 23:2282.

[77] The most complete daily account of the New York convention was prepared by Francis Childs, the publisher of the New York Daily Advertiser. He took detailed shorthand notes of the convention, which were published as a pamphlet, The Debates and Proceedings of the Convention of the State of New York. DHRC, 19:lxix.

[78] DHRC, 23:2311.

[79] DHRC, 23:2369.

[80] Examples of the biblical reference can be found in Jeremiah 50:6 and Ezekiel 34:6. DHRC, 23:2283.

[81] https://rotunda-upress-virginia-edu.i.ezproxy.nypl.org/founders/RNCN-02-23-02-0001-0009-9001

[82] DHRC, 4:362. By comparison, the phrase “the wheels of government” (without a second “the”) appears twenty times, including a letter from George Washington to Benjamin Lincoln dated 28 August 1788. DHRC, 23:2462.