The Federal Farmer’s Fingerprints

The Federal Farmer / Elbridge Gerry Authorship Thesis

(Uncovering the Federal Farmer – Part 5)

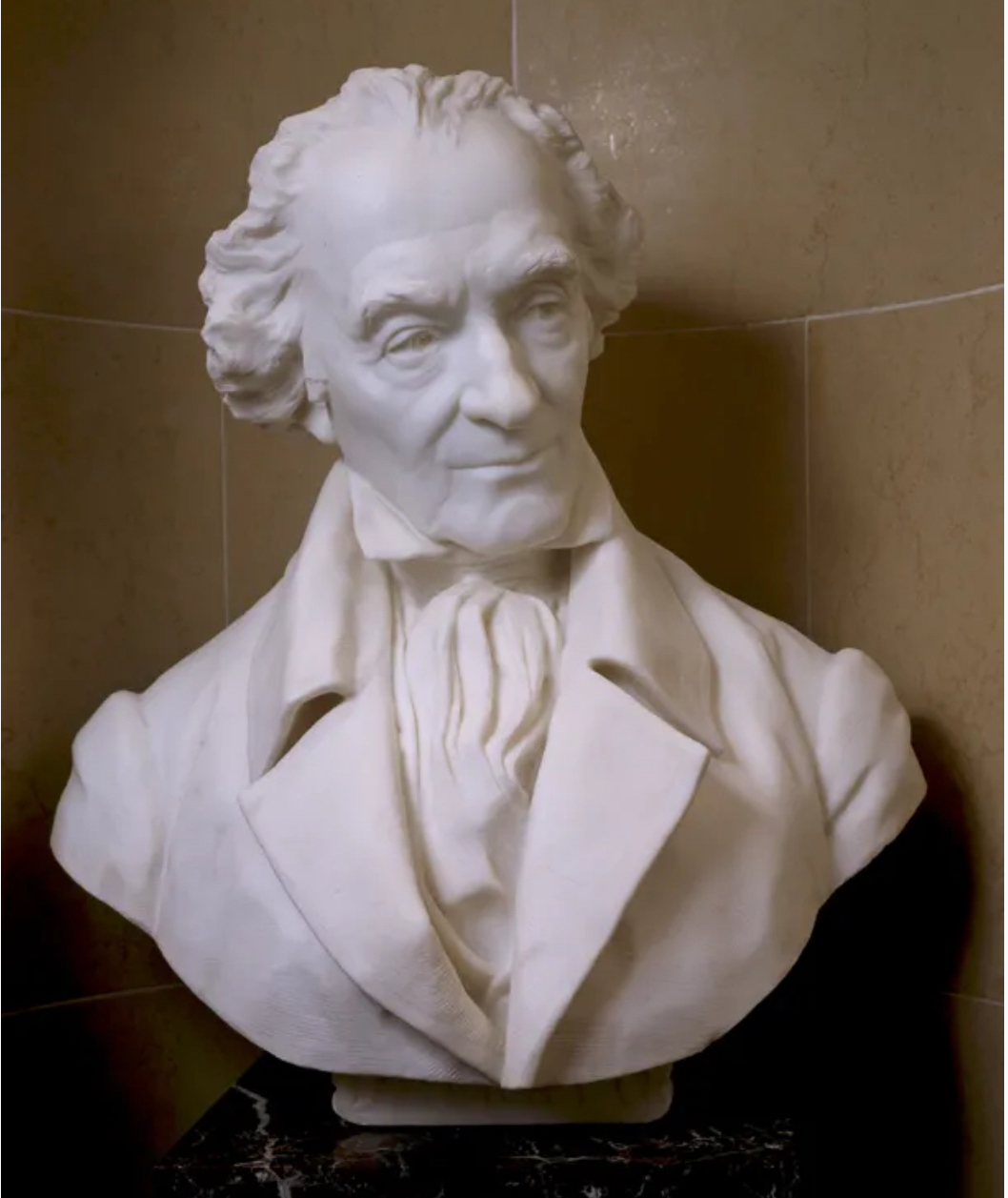

Elbridge Gerry was one of three delegates who refused to sign the proposed Constitution. In a letter to the Massachusetts legislature Elbridge Gerry went public with the reasons for his opposition.[1] Gerry explained that it was “painful” for him to differ from his respectable colleagues. The first of Gerry’s “principal objections” was that there was no adequate provision for “a representation of the people.” This identical phrase repeatedly appears in The Letters of the Federal Farmer, arguably the most important of the Antifederalist essays during the ratification debate.

The Federal Farmer’s objective of securing “a representation of the people” is an example of a signature phrase – or fingerprint – connecting Elbridge Gerry and the Federal Farmer. It also turns out that the same signature phrase, “a representation of the people,” is derived from the Massachusetts Constitution. Yet, in 1787 this term of art does not appear in any of the other twelve state constitutions. Set forth below is a detailed discussion of Elbridge Gerry’s linguistic fingerprints which taken together prove that he was the Federal Farmer.

This blog post, Uncovering the Federal Farmer (Part 5), is the fifth installment of a multi-part series attempting to demystify the Federal Farmer. Part 1 revealed an unpublished and undated manuscript by Elbridge Gerry which sheds new light on his identity as the Federal Farmer. Part 2 continued with a discussion of Gerry, the elusive founding father who was one of the Constitutional Convention’s most outspoken and “consistently contrary” delegates. Part 2 also examines the historiography of the Federal Farmer, long believed to have been Richard Henry Lee. Part 3 provides an overview of the mounting evidence supporting John Kaminski’s attribution that Elbridge Gerry was the Federal Farmer, not Melancton Smith as commonly assumed by 20th century historians.

Part 4 takes a deep dive into archival evidence and the historic record. While Kaminski’s attribution is in itself compelling, Statutesandstories.com has uncovered additional evidence which helps confirm the conclusion that Elbridge Gerry was in fact the Federal Farmer. While no single piece of evidence is alone conclusive, it is believed that the combined weight of the mutually reinforcing evidence is striking. The totality of the following evidence, combined with Kaminski’s attribution analysis, is hereinafter referred to as the Federal Farmer – Elbridge Gerry Authorship Thesis (“FEAT”). It is anticipated that independent scholarly review of the FEAT will support the conclusion that Kaminski’s attribution is now settled. In other words, it is the goal of this essay to put to rest “by far the most controversial and long-lived debate” over the authorship of a pseudonymous essay.

Picking up where Part 4 left off, Part 5 presents additional evidence in support of the Federal Farmer – Elbridge Gerry Authorship Thesis. Part 5 identifies signature phrases used by Elbridge Gerry and the Federal Farmer, which are analogous to Gerry’s linguistic fingerprints.

Part 6 will continue with a discussion of additional attribution evidence linking Gerry and the Federal Farmer. Interestingly, Elbridge Gerry was not a typical Antifederalist. Some of the Federal Farmer’s positions might be described as “unexpected Antifederalist arguments.” Although he had reservations about doing so, Elbridge Gerry served in the first Federal Congress. As to be expected, Gerry’s speeches in Congress align with the positions of the Federal Farmer. Part 6 concludes with a discussion of “Gerry’s endgame,” the adoption of constitutional amendments, which further illustrate Gerry’s identity as the Federal Farmer.

Stylistic Fingerprints and Methodology

Separate and apart from Gerry’s formal objections to the Constitution, the Letters of the Federal Farmer are replete with Gerry’s unmistakable “fingerprints” – word combinations and patterns reflective of Gerry’s signature linguistic style.[2] There is no doubt that many of these fingerprints overlap with the Federal Farmer’s objections and underlying arguments. Yet, for analytical purposes it is useful to characterize Gerry’s linguistic fingerprints separately from Gerry’s objections and underlying arguments.

Admittedly, distinguishing between Gerry’s “objections,” “fingerprints” and underlying “arguments” is necessarily arbitrary. Nevertheless, due to the sheer volume of evidence, these distinctions are useful analytical and organizational tools. The label linguistic fingerprint will be applied to relatively unique signature phrases repeatedly used by Gerry and the Federal Farmer.

By contrast, a supporting “argument” made by Gerry would be of less evidentiary value to the extent that other Antifederalists make similar arguments. The final category of “unexpected Antifederalist arguments” is viewed as particularly relevant for the FEAT thesis. Part 5 and 6 identify a dozen “signature phrases,” dozens of supporting “arguments,” but only a handful of “unexpected Antifederalist arguments.” The “unexpected” Antifederalist arguments, or minority Antifederalist views, illustrate the daylight between Gerry and his other Antifederalist colleagues.

“A representation of the people”

Both Gerry and Federal Farmer repeatedly use the phrase “a representation of the people” and permutations thereof. This signature fingerprint appears in the very first paragraph of both Federal Farmer No. 1 and No. 2. The Federal Farmer’s conclusions are set forth in Federal Farmer No. 5, the final essay of the first Federal Farmer pamphlet. Despite the existence of many good safeguards, Federal Farmer No. 5 could not be more clear. “[T]he value of every feature in this system is vastly lessened for the want of that one important feature in a free government, a representation of the people.” This perfectly aligns with the first objection listed by Gerry in his October 18th letter to the Massachusetts legislature, “no adequate provision for a representation of the people.”

The topic of representation is the central theme of Federal Farmer No. 2. The opening paragraph of Federal Farmer No. 2 uses versions of the phrase seven times as follows, illustrating the centrality of the concept to the Federal Farmer’s thinking:

The essential parts of a free and good government are a full and equal representation of the people in the legislature, and the jury trial of the vicinage in the administration of justice—a full and equal representation, is that which possesses the same interests, feelings, opinions, and views the people themselves would were they all assembled—a fair representation, therefore, should be so regulated, that every order of men in the community, according to the common course of elections, can have a share in it—in order to allow professional men, merchants, traders, farmers, mechanics, etc. to bring a just proportion of their best informed men respectively into the legislature, the representation must be considerably numerous—We have about 200 state senators in the United States, and a less number than that of federal representatives cannot, clearly, be a full representation of this people, in the affairs of internal taxation and police. were there but one legislature for the whole union. The representation cannot be equal, or the situation of the people proper for one government only—if the extreme parts of the society cannot be represented as fully as the central—It is apparently impracticable that this should be the case in this extensive country—it would be impossible to collect a representation of the parts of the country five, six, and seven hundred miles from the seat of government.

Federal Farmer No. 2 argues that in a free country power is properly lodged with the “guardians of the people.” According to the Federal Farmer, power can only safely be used by “an able executive and judiciary, a respectable senate, and a secure, full and equal representation of the people.” The Federal Farmer defines “a full and equal representation” as “that which possesses the same interests, feelings, opinions, and views the people themselves would were they all assembled.” Yet, after a careful examination of the proposed Constitution Federal Farmer No. 2 concludes that, “we must clearly perceive an unnatural separation of these powers from the substantial representation of the people.”

The small size and organization of the House of Representatives is discussed in Federal Farmer No. 3. In comparing the different regions of the nation, Federal Farmer No. 3 observed that the northern[3] states were “very democratic,” in comparison with the southern states where a “dissipated aristocracy” prevailed, composed chiefly of wealthy planters and slaves. Federal Farmer No. 3 also describes why the proposed Constitution fails to secure a true or proper representation of the people:

- “In considering the practicability of having a full and equal representation of the people from all parts of the union, not only distances and different opinions, customs, and views, common in extensive tracts of country are to be taken into view but many differences peculiar to Eastern, Middle, and Southern states.”

- “Not only the determination of the convention in this case, but the situation of the states, proves the impracticability of collecting, in any one point, a proper representation.”

- “If a proper representation be impracticable, then we shall see this power resting in the states, where it at present ought to be, and not inconsiderately given up.”

- I am aware it is said, that the representation proposed by the new constitution is sufficiently numerous; it may be for many purposes; but to suppose that this branch is sufficiently numerous to guard the rights of the people in the administration of the government, in which the purse and sword is placed, seems to argue that we have forgot what the true meaning of representation

The phrase also appears in Federal Farmer No. 5, 7, 8 and 11. For example, Federal Farmer No. 5 reiterates the “important” objection “that is no substantial representation of the people.” Federal Farmer No. 7 likewise emphasizes that “a fair and equal representation is that in which the interests, feelings, opinions and views of the people are collected, in such manner as they would be were the people all assembled. Having made these general observations, I shall proceed to consider further my principal position, viz. that there is no substantial representation of the people.”

Federal Farmer No. 8 compared representation in England, Rome and other countries. Evaluating the representation in the House of Commons, Federal Farmer 8 concluded that “equal liberty prevails in England, because there was a representation of the people.” Following the Norman invasion in 1066, the “body of the people, about four or five millions, then mostly a frugal landed people, were represented by about five hundred representatives, taken not from the order of men which formed the aristocracy, but from the body of the people, and possessed of the same interests and feelings.” Federal Farmer No. 11 evaluated representation in the Senate. “It is not to be presumed that we can form a genuine senatorial branch in the United States a real representation of the aristocracy and balance in the legislature any more than we can form a genuine representation of the people.”

It is likely that one of the reasons why the Federal Farmer was so interested in this topic is because “a representation of the people” was enshrined as a core principle in the Massachusetts Constitution.[4] In particular, the Massachusetts House of Representatives was explicitly required to be based on “a representation of the people,” founded upon the “principle of equality.”

The Federal Farmer was not the only Antifederalist to discuss the concept of representation. For example, both Cato and Brutus use the phrase. In both cases, Gerry’s use of the phrase preceded Cato and Brutus. Moreover, no other author during the ratification campaign made the same repeated use of this signature fingerprint with the same frequency and emphasis. Cato No. 4 used the phrase “a just and full representation of the people” only a single time.[5] Brutus uses the phrase “a representation of the people” four times.[6] Yet, in two of these four examples Brutus employs a slightly different phraseology: “a representation of the people of America.”[7] The Federal Farmer never uses this seven-word phrase, which was used two times by Brutus.[8]

As described by Gerry’s biographer, “[the key to Gerry’s role in the Constitutional Convention lies in his republicanism.”[9] Note that Federal Farmer’s concern over the issue of “a representation of the people” is separate from the issue of the representation of the states. Accordingly, the Great Compromise between large and small states was not a principal objection by Gerry or the Federal Farmer.

“Guardians of the people”

Another fingerprint which identifies Gerry as the Federal Farmer is the phrase “guardians of the people.” Federal Farmer No. 1 compared the three different approaches to consolidation: the status quo “federal plan” where the states are distinct republics, “complete” consolidation which is objectionable, and “partial” consolidation. As described by Federal Farmer No. 1, under the first approach the state governments are the “principal guardians of the people’s rights.” Yet, the Federal Farmer recognized that the status quo “federal plan” could not be “depended upon to answer the purposes of government” under the Articles of Confederation.

A consistent theme of the Federal Farmer was that governmental power should be lodged with the people. According to Federal Farmer No. 2, “[t]hese powers must be lodged somewhere in every society; but then they should be lodged where the strength and guardians of the people are collected.” Reasoning that the state governments are closer to the people, Federal Farmer No. 2 argued that it is more probable “that the state governments will possess the confidence of the people, and be considered generally as their immediate guardians.”

Federal Farmer No. 3 discussed the proposed federal courts. Given Gerry’s insistence during the Convention on the need to protect the right to a jury trial, it should come as no surprise that the Federal Farmer No. 3 agreed that the right to a “jury trial is not secured at all in civil causes.” Federal Farmer No. 4 focused on jury trials which were “essential in every free country,” as they allowed participation by the “common people.” Federal Farmer No. 4 explained that “[t]heir situation as jurors and representatives, enables them to acquire information and knowledge in the affairs and government of the society; and to come forward, in turn, as the centinels and guardians of each other.”

Federal Farmer Nos. 13, 15 and 17 also use the phrase “guardians of” the people as follows:

- “will esteem it a higher honor to be selected as the guardians of a free people” FF13

- “…. stand as the guardians of each others rights, and to restrain, by regular and legal measures, those who otherwise might infringe upon them.” FF15

- “This is all true; but of what avail will these circumstances be if the state governments, thus allowed to be the guardians of the people, possess no kind of power by the forms of the social compact, to stop in their passage, the laws of congress injurious to the people.” FF17

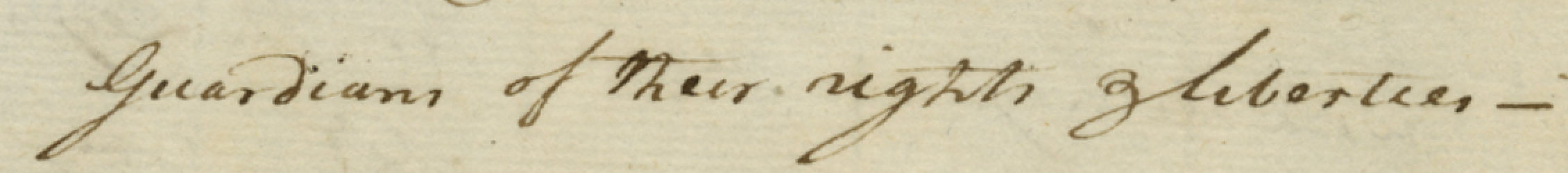

By comparison, Brutus never used this phrase, “guardians of the people.” Yet, Gerry’s letter to Massachusetts legislature declared that “a free people are the proper guardians of their rights and liberties.” Similarly, at the Constitutional Convention on July 21 Gerry used the phrase “guardians of the rights of the people.”

“Designing men” v. “Best men”

Both Gerry the Federal Farmer repeatedly use the phrase “designing men.” On May 31, Gerry expressed the concern at the Constitutional Convention that the people were misled by “false reports circulated by designing men.” He repeated the phrase on July 19. The Federal Farmer does not speak well of designing men, who were variously described as “empty,” “imprudent,” and “unthinking.” At the other end of the spectrum, the Federal Farmer welcomed a government consisting of the “best men.”

The Federal Farmer used the phrase “designing men” four times. The phrase designing men is used in both of the two published Federal Farmer pamphlets as follows:

- “The uneasy and fickle part of the community may be prepared to receive any form of government; but, I presume, the enlightened and substantial part will give any constitution, presented for their adoption, a candid and thorough examination: and silence those designing or empty men, who weakly and rashly attempt to precipitate the adoption of a system of so much importance” (FF1)

- “…. this only proves, that the power would be improperly lodged in congress, and that it might be abused by imprudent and designing men.” (FF3)

- “There appears to me to be not only a premature deposit of some important powers in the general government-but many of those deposited there are undefined, and may be used to good or bad purposes as honest or designing menshall prevail.” (FF4)

- “but we ought to examine facts, and strip them of the false colourings often given them by incautious observations, by unthinking or designing men.” (FF17)

The phrase “designing men” was used by several delegates to the Convention. Nevertheless, Gerry is the first delegate to do so, as reported in Madison’s notes:

- “Mr. Gerry. The evils we experience flow from the excess of democracy. The people do not want virtue; but are the dupes of pretended patriots. In Massts. it has been fully confirmed by experience that they are daily misled into the most baneful measures and opinions by the false reports circulated by designing men, and which no one on the spot can refute.”[10]

- Madison’s notes on July 19 similarly record Gerry observing that, “[t]he people are uninformed, and would be misled by a few designing men.”[11]

By contrast, on June 4th Gerry mentioned the goal that “best men” in the community would comprise the legislative branch.[12] On July 24 Gerry generally described the governors as “the best men.” As is the case with the phrase “designing men,” Gerry was the first delegate to use the term “best men” at the Convention. The Federal Farmer used the phrase “the best men” three times, twice in Federal Farmer No. 12 and once in Federal Farmer No. 17.

“Respectable assembly” of “respectable men”

Gerry and the Federal Farmer described the Convention as a “respectable assembly” consisting of “respectable men.” Federal Farmer No. 1 offered to view the convention “with proper respect,” but proposed to allow the Constitution to rest on its merits. Describing the delegates to the Convention as “men of abilities and integrity,” Federal Farmer No. 1 emphasized that the “democratic and aristocratic parts of the community” were disproportionately represented.[13]

In Gerry’s October 18 letter to the Massachusetts legislature he wrote that:

- It was painful for me, on a subject of such national importance, to differ from the respectable Members who signed the constitution.

- It may be urged by some, that an implicit confidence should be placed in the Convention: but however respectable the members may be who signed the constitution, it must be admitted, that a free people are the proper Guardians of their rights & liberties—that the greatest men may err—& that their errors are sometimes, of the greatest magnitude.

Federal Farmer No. 5 complimented the Convention as a “respectable assembly of men,” predicting that “America probably never will see an assembly of men of a like number, more respectable.” This is evidence of the Federal Farmer’s moderation and first-hand information.

Even so, Federal Farmer No. 5 still expressed confidence in the state conventions which retained the “weight of respectability”:

Though each individual in the state conventions will not, probably, be so respectable as each individual in the federal convention, yet as the state conventions will probably consist of fifteen hundred or two thousand men of abilities, and versed in the science of government, collected from all parts of the community and from all orders of men, it must be acknowledged that the weight of respectability will be in them.”

Federal Farmer No. 6 repeated a similar sentiment. “The convention, as a body, was undoubtedly respectable; it was, generally, composed of members of the then and preceding Congresses: as a body of respectable men we ought to view it.” In the same paragraph, Federal Farmer No. 6 called out the ardent advocates of the Constitution for their “indecent virulence” addressed to “M[aso]n, G[err]y and L[e]e.”

“Fountain of….”

Both Gerry and the Federal Farmer used the image of a “fountain” of power and politics, to be kept pure. Federal Farmer No. 11 speaks of “the fountain of corruption.” Federal Farmer No. 13 described the legislature as “the great fountain of power” which “ought to be kept as pure and uncorrupt as possible.” Federal Farmer No. 18 warned of the corrupting influences that might impact the “fountain of politics” in the proposed new capital city:

Such a city, or town, containing a hundred square miles must soon be the great. the visible, and dazzling centre, the mistress of fashions, and the fountain of politics. There may be a free or shackled press in this city, and the streams which may issue from it may overflow the country. and they will be poisonous or pure, as the fountain may be corrupt or not. But not to dwell on a subject that must give pain to the virtuous friends of freedom, I will only add, can a free and enlightened people create a common head so extensive, so prone to corruption and slavery, as this city probably will be, when they have it in their power to form one pure and chaste, frugal and republican.

The Federal Farmer’s concern that the capital city would be “prone to corruption” aligns with Gerry’s observation at the Convention that “neither the Seat of a State Govt. nor any large commercial City should be the seat of the Genl. Govt.”[14]

In a letter to the President of Congress in 1780 about the principle of parliamentary privilege Gerry inquired “by what means the fountain of the Confederacy is to be kept pure”?[15] In 1781 Gerry wrote to John Adams celebrating that the governments of the states “have now obtained such a consistency and establishment, which are every day increasing: the people feel so much their dignity and importance, in being the fountain of power and honor.”[16]

“Unlimited powers”

Both Gerry and the Federal Farmer objected to various “unlimited powers” being vested in Congress. When Gerry enumerated his objections at the Constitutional Convention on September 15, he listed the “unlimited power of Congress over the places of election.”[17] In his Reply to Landholder, Gerry elaborated on the objections in his October 18 letter to the Massachusetts legislature. Gerry explained that his third objection, that “some of the powers of the federal legislature are ambiguous and others are indefinite and dangerous,” referred to “the unlimited power of Congress” to keep a standing army in times of peace.[18]

Federal Farmer No. 3 raised the same concern that “congress will have unlimited power to raise armies, and to engage officers and men for any number of years.” The Federal Farmer discussed the unlimited power of Congress five times as follows:

- It was inadvisable to lodge “unlimited power” in only 65 Representatives and 26 Senators (FF10)

- Warned against giving Congress “unlimited powers to raise taxes by imposts” (FF17)

- Warned against giving Congress “unlimited power to raise monies by excises and direct taxes” (FF17)

- Emphasized the importance of checks on Congress as “the powers of the union in matters of taxation, will be too unlimited; further checks, in my mind, are indispensably necessary.” (FF17)

- Argued against “powers unlimited as to the purse and sword, to raise men and monies” (FF17).

It is also noteworthy that during his career in Congress Gerry was particularly opposed to standing armies. “Given Gerry’s republican outlook, one of his greatest fears was that of a standing army within a ‘free state.’ Apprehensive lest the militia created to counter the British be turned against the American people, Gerry insisted upon a highly decentralized military force.” Thus, Gerry was interested in checking both military power and political power.[19]

“Dupes of___” and “pretended ___”

Both Gerry and the Federal Farmer used the phrase “dupes of___” and “pretended ___.” At the Constitutional Convention Gerry indicated that “[t]he evils we experience flow from the excess of democracy. The people do not want [i.e., lack] virtue; but are the dupes of pretended patriots.”[20] This is similar to statements in Federal Farmer No. 6 and 8, along with similar expressions in Gerry’s private correspondence.

The Federal Farmer No. 6 used the phrase “pretended federalists” as follows:

Some of the advocates are only pretended federalists; in fact they wish for an abolition of the State governments. Some of them believe to be honest federalists, who wish to preserve substantially the state governments united under an efficient federal head; and many of them are blind tools without any object. Some of the opposers also are only pretended federalists, who want no federal government, or one merely advisory.

Federal Farmer No. 8 observed that the people were “the dupes of artifice” as follows:

The people were too numerous to assemble, and do any thing properly themselves; the voice of a few, the dupes of artifice, was called the voice of the people. It is difficult for the people to defend themselves against the arts and intrigues of the great, but by selecting a suitable number of men fixed to their interests to represent them and to oppose ministers and senators. And the people’s all depends on the number of the men selected, and the manner of doing it.

A review of Gerry’s correspondence reveals his repeated use of the phrase “dupe” in similar contexts as follows:

- But as the Measure is defeated by the Intrigues of a European Court, aided by her Dupes in America, your presence here will be necessary, as well to prevent the ill Consequences which may result from your sudden Departure from the Court of Russia, as to do Justice to your Merit.[21]

- “Duped by the artful representatives of foreign powers”[22]

- “Your political Sin, was your Refusal to be a Dupe to foreign Influence”[23]

- “I was duped amongst the rest”[24]

- “dupes to their own prejudices”[25]

- “Dupe of the policy of that nation”[26]

Gerry also used the term “artifice” / “artifices” during the early days of the Constitutional Convention. On June 6, Gerry observed that “[m]en of indigence, ignorance & baseness, spare no pains however dirty to carry their point agst. men who are superior to the artifices practiced.”[27] While McHenry’s notes are only skeletal, Gerry may also have used the term “artifice” on May 31.[28] Likewise, in a letter to Samuel Holten, Gerry indicated that “I know too well the fatigue & trouble attending an honorable & faithful Discharge of Public Trust; the interested views, and the little artifices of those who are seeking offices.”[29]

Federal Farmer No. 1 warned of the “secret instigations of artful men.” Federal Farmer No. 4 cautioned that once power is transferred “from the many to the few,” the few will be exceedingly “artful and adroit” in holding onto power. Federal Famer No. 4 concluded that the proposed constitution was a transfer of power to “the artful and ever active aristocracy.”

“Aristocratical” interests / branch / junto

Both Gerry and the Federal Farmer were wary of aristocracy and allowing “aristocratical” interests to become too powerful. As described by historians and constitutional scholars, Gerry “was driven by a nearly pathological fear of the misuse of power.” During and after the Revolution Gerry had been one of the most outspoken in denouncing the evils of concentration of power in the hands of the few.[30] Gerry brought to the Convention “many ideas to which he had subscribed in the Revolution: an aversion to monarchical and aristocratic traditions, standing armies, and arbitrary judges and courts.”[31] Gerry warned the Convention on August 14 that the proposed Constitution was “as compleat an aristocracy as ever was framed.” Distrust of aristocracy – bordering on hostility – and the frequent use of the adjective “aristocratical” are fingerprints which connect Gerry and the Federal Farmer. Both Gerry and the Federal Farmer worried about seeding too much control to an aristocratic “junto.”[32]

The Federal Farmer uses the adjective “aristocratical” eight times as follows. This word is generally used by the Federal Farmer to describe aristocratical men or the aristocratical class. The aristocratical class is frequently compared to the democratical class, as follows:

- “Pennsylvania appointed principally those men who are esteemed aristocratical.” (FF1)

- Our governments have been new and unsettled; and several legislatures, by making tender, suspension, and paper money laws, have given just cause of uneasiness to creditors. By these and other causes, several orders of men in the community have been prepared, by degrees, for a change of government; and this very abuse of power in the legislatures, which, in some cases, has been charged upon the democratic part of the community, has furnished aristocratical men with those very weapons, and those very means, with which, in great measure, they are rapidly effecting their favourite object. (FF1)

- It is extremely clear that these writers had in view the several orders of men in society, which we call aristocratical, democratical, merchantile, mechanic, &c. and perceived the efforts they are constantly, from interested and ambitious views. disposed to make [efforts?] to elevate themselves and oppress others.” (FF7)

- the first class is the aristocratical (FF7)

- It is easy to perceive that men of these two classes, the aristocratical, and democratical, with Views equally honest, have sentiments widely different, especially respecting public and private expenses, salaries. taxes, &c. (FF7)

- Hence it is that the best practical representation, even in a small state, must be several degrees more aristocratical than the body of the people. (FF9)

- Could we separate the aristocratical and democratical interests: compose the senate of the former, and the house of assembly of the latter, they are too unequal in the United States to produce a balance. (FF11)

Gerry likewise used the adjective “aristocratical” on several occasions before and after the Convention. He was generally not being complementary when he deployed the word aristocratical:

- Gerry to John Adams, 25 April 1785: “Your political Sin, was your Refusal to be a Dupe to foreign Influence, & the Consequence was a most vigorous Exertion of that Influence, & of its Dupes [strikeout] Tools in America, consisting of an high aristocratical party, to dismiss You from, or to teaze You into a Relinquishment of office. this was seen thro by every [strikeout] intelligent Republicans, who considered the Struggle as nothing more, nor less than this, whether Republicanism or Aristocracy should prevail!”

- Gerry to VP of Mass Convention Jan 21, 1788 (Farrand, 3:266): “It was not reasonable to suppose the aristocratical branch would be as saving of the public money as the democratical branch….”

- Gerry to ?, dated Feb/March 1791 (Sang Collection): “[S]o far as We had an aristocratical principle in the federal constitution….the Senate may be considered as the hot bed of aristocracy.” This “principle” was “disposed naturally to encroach & required vigilance.”

One of the Federal Farmer’s biggest concerns was that the proposed Constitution was too aristocratic. Multiple letters by the Federal Farmer discussed aristocracy, usually in the context of criticizing the proposed Constitution:

- “Had they attended, I am pretty clear, that the result of the convention would not have had that strong tendency to aristocracy now discernable in every part of the plan. There would not have been so great an accumulation of powers, especially as to the internal police of the country, in a few hands, as the constitution reported proposes to vest in them—the young visionary men, and the consolidating aristocracy, would have been more restrained than they have been.” (FF1)

- We shall view the convention with proper respect -and, at the same time, that we reflect there were men of abilities and integrity in it, we must recollect how disproportionably the democratic and aristocratic parts of the community were represented – Perhaps the judicious friends and opposers of the new constitution will agree, that it is best to let it rest solely on its own merits, or be condemned for its own defects. (FF1)

- “The election of this officer, as well as of the president of the United States seems to be properly secured; but when we examine the powers of the president, and the forms of the executive, shall perceive that the general government, in this part, will have a strong tendency to aristocracy, or the government of the few.” (FF13)

- “… important measures may, sometimes, be adopted by a bare quorum of members, perhaps, from a few states, and that a bare majority of the federal representatives may frequently be of the aristocracy, or some particular interests, connections, or parties in the community, and governed by motives, views, and inclinations not compatible with the general interest.” (FF17)

According to the Federal Farmer No. 7 there were three types of aristocracy. The Federal Farmer also distinguished between the “natural aristocracy” and the “natural democracy.” Federal Farmer No. 7 was particularly worried about “an aristocratic faction: a junto of unprincipled men, often distinguished for their wealth or abilities, who combine together and make their object their Private interests and aggrandizement,” which was “particularly to be guarded against.” [33]Federal Farmer No. 10 expressed the “undeniable” concern that “the federal government will be principally in the hands of the natural aristocracy.” In discussing the Senate, Federal Farmer No. 13 reiterated that “[b]y giving the senate, directly or indirectly, an undue influence over the representatives, and the improper means of fettering, embarrassing, or controlling the president or executive, we give the government, in the very out set, a fatal and pernicious tendency to that middle undesirable point—aristocracy.”

These concerns of the Federal Farmer align with the same concerns expressed by Gerry at the Convention. According to Robert Yates’ notes on June 29, Gerry opined: “Aristocracy is the worst kind of government.”[34] During the Convention Gerry admitted that there was a role for both aristocratic and democratic forces in government.[35] Yet, by August 14 Gerry concluded that the proposed Constitution would result in an aristocratic junto:

We cannot be too circumspect in the formation of this System. It will be examined on all sides and with a very suspicious eye. The People who have been so lately in arms agst. G. B. for their liberties, will not easily give them up. He lamented the evils existing at present under our Governments, but imputed them to the faults of those in office, not to the people. The misdeeds of the former will produce a critical attention to the opportunities afforded by the new system to like or greater abuses. As it now stands it is as compleat an aristocracy as ever was framed If great powers should be given to the Senate we shall be governed in reality by a Junto as has been apprehended.[36]

Admittedly, the topic of aristocracy was frequently discussed by delegates to the Convention. Nonetheless, it is useful to compare Gerry’s distrust for aristocracy with the opinions of other delegates. For example, on July 2 Morris explained the reasons to make the “aristocratic body as independent and firm as the democratic.” “By thus combining & setting apart, the aristocratic interest, the popular interest will be combined agst. it. There will be a mutual check and mutual security.”[37]

Gerry’s distrust of aristocracy can be traced back well before the Convention. For example, in 1783 he warned against “changing our Form of Government, established at an amazing expense of Blood & Treasure, for a vile Aristocracy or an arbitrary Monarchy.”[38] As a member of Congress in 1784 he wrote that he had become obnoxious “to the aristocratic Party.”[39]

Concern for a possible “civil war”

Both Gerry and the Federal Farmer were concerned about provoking a civil war. Indeed, the perceived risk of triggering a civil war was likely one of the reasons for Gerry’s moderation. On August 23 he warned the Convention against pushing the experiment too far due to the risk of precipitating a “civil war.”[40] On the last day of the Convention he repeated his fears that a “civil war” might result. He instead preferred that the proposed Constitution be “in a more mediating shape, in order to abate the heat and opposition of parties.”[41]

Gerry’s concern about a civil war aligns with Federal Farmer No. 1 who expressed the same concerns:

- “This consolidation of the states has been the object of several men in this country for some time past. Whether such a change can ever be effected in any manner; whether it can be effected without convulsions and civil wars; whether such a change will not totally destroy the liberties of this country-time only can determine.” (FF1)

- “The conduct of several legislatures, touching paper money, and tender laws, has prepared many honest men for changes in government, which otherwise they would not have thought of—when by the evils, on the one hand, and by the secret instigations of artful men, on the other, the minds of men were become sufficiently uneasy, a bold step was taken, which is usually followed by a revolution, or a civil war. A general convention for mere commercial purposes was moved for—the authors of this measure saw that the people’s attention was turned solely to the amendment of the federal system; and that, had the idea of a total change been started, probably no state would have appointed members to the convention.” (FF1)

Gerry expressed the same concerns in correspondence with his wife Ann during the Convention and in letters to friends and family after the Convention:

- Gerry to Ann dated 26 August 1787: “I am exceedingly distrest at the proceedings of the Convention being apprehensive, and almost sure they will if not altered materially lay the foundation of a civil War.”

- Gerry to Samuel Gerry dated 28 January 1788: “I expect we shall be in a civil War, but may God avert the evil.”

- Gerry to Samuel Gerry dated 6 April 1788: “… the convulsons of the public augur no good, & happy is the individual who has last to do with them. I expect they will terminate in a civil war & ruin to the country must be the consequence.”

- Gerry to James Warren dated 22 March 1789: “… to oppose it would be to sow the seeds of a civil war and lay the foundation of a military tyrany.”

“Defects” versus efforts to make the Federal government more “efficient”

Gerry and the Federal Farmer identified substantial “defects” with the Constitution. They likewise admitted that the Articles of Confederation also had defects. Both Gerry and the Federal Farmer supported efforts by the Convention to make the Federal Government more “efficient.” Yet, Gerry and the Federal Farmer both agreed that the proposed Constitution was “very defective” and required amendment.

Federal Farmer No. 4 described the Constitution as “essentially defective:

- “I am sensible, thousands of men in the United States, are disposed – to adopt the proposed constitution, though they perceive it to be essentially defective, under an idea that amendment of it, may be obtained when necessary. (FF4)

Federal Farmer No. 6 listed the “principal defects” of the proposed Constitution, which closely align with Gerry’s objections:

- “I shall, in a few letters, more particularly endeavour to point out the defects and propose amendments.” (FF6)

- “And as to the principal defects, as the smallness of the representation, the insecurity of elections, the undue mixture of powers in the senate, the insecurity of some essential rights, &c.” (FF6)

Federal Farmer No. 1 indicated that the “greatest defects” are from the tenacity of the small states to obtain equal representation in Senate. Federal Farmer No. 1 repeatedly referred to defects and attempted to be judicious evaluating the defects with the Articles of Confederation and the defects with the proposed Constitution:

- “… from the tenacity of the small states to have an equal vote in the senate, probably originated the greatest defectsin the proposed plan.” (FF1)

- “My object has been to join with those who have endeavoured to supply the defects in the forms of our governments by a steady and proper administration of them.” (FF1)

- “It must, however, be admitted, that our federal system is defective, and that some of the state governments are not well administered; but, then, we impute to the defects in our governments many evils and embarrassments which are most clearly the result of the late war.” (FF1)

- “Perhaps the judicious friends and opposers of the new constitution will agree, that it is best to let it rest solely on its own merits, or be condemned for its own defects.” (FF1)

Federal Farmer No. 5 reiterated the “radical defects” in the proposed Constitution were “dangerous to freedom” and destructive of the principles of republican government. Federal Farmer No. 12 described the Constitution as “very defective”[42]:

- “While the radical defects in the proposed system are not so soon discovered, some temptations to each state, and to many classes of men to adopt it, are very visible.” (FF5)

- “This subject of consolidating the states is new: and because forty or fifty men have agreed in a system, to suppose the good sense of this country, an enlightened nation, must adopt it without examination, and though in a state of profound peace, without endeavouring to amend those parts they perceive are defective, dangerous to freedom, and destructive of the valuable principles of republican government—is truly humiliating.” (FF5)

- “I have, in the course of these letters observed, that there are many good things in the proposed constitution, and I have endeavoured to point out many important defects in it.” (FF5)

- “On carefully examining the parts of the proposed system, respecting the elections of senators, and especially of the representatives, they appear to me to be both ambiguous and very defective.” (FF12)

During and after the Convention Gerry recognized that the Constitution had “essential” defects. As a member of Congress he stated that the Constitution was “very defective” and required amendment.

- “accommodation is absolutely necessary, and defects may be amended by a future convention.” [Gerry at Convention on 7/2 (Yates notes)][43]

- “as to the amendments proposed by Congress, they will not affect those questions or serve any other purposes than to reconcile those who had no adequate idea of the essential defects of the Constitution.” [Gerry to John Wendell, 14 Sept 1789][44]

- “He wished gentlemen to consider the situation of the states—seven out of thirteen had thought the constitution very defective, yet five of them has adopted it with a perfect reliance on congress for its improvement: Now what will these states feel if the subject is discussed in a select committee, and their recommendations totally neglected.” [Gerry in Congress, 21 July 1789][45]

Need for an “efficient” federal system

Both Gerry and the Federal Farmer shared the goal of creating a more “efficient” federal system. Both agreed that the Articles of Confederation were inadequate. Federal Farmer No. 1, 3 and 6 discussed the need for Congress to have “efficient powers” to be “more efficient” and for state governments to be preserved under “an efficient federal head”:

- “Touching the first, or federal plan. I do not think much can be said in its favor: The sovereignty of the nation, without coercive and efficient powers to collect the strength of it cannot always be depended on to answer the purposes of government: and in a congress of representatives of sovereign states, there must necessarily be an unreasonable mixture of powers in the same hands.” (FF1)

- “I am fully convinced that we must organize the national government on different principals, and make the parts of it more efficient and secure in it more effectually the different interests in the community: or else leave in the State governments some powers propose[d] to be lodged in it—at least till such an organization shall be found to be practicable. (FF3)

- “Some of them I believe to be honest federalists, who wish to preserve substantially the state governments united under an efficient federal head; and many of them are blind tools without any object.” (FF6)

When Gerry arrived at the Convention he was worried by the “levilling spirit” and the implications of Shays’s Rebellion.[46] During the early days of the Convention Gerry agreed with his colleagues about the need to establish an “efficient” federal government. Gerry expressed similar views in his 18 October letter to the Massachusetts Legislature and in when he agreed to serve in the first Federal Congress:

- “… the object of this meeting is very important in my mind – unless a system of government is adopted by compact, force I expect will plant the standard: for such an anarchy as now exists cannot last long. Gentlemen seem to be impressed with the necessity of establishing some efficient System, & I hope it will secure US against domestic as well as foreign Invasions” [Gerry to James Monroe, 11 June 1787].[47]

- “I did not conceive that these powers extended to the formation of the plan proposed, but the Convention being of a different opinion, I acquiesced in it, being fully convinced that to preserve the union, an efficient Government was indispensibly necessary; & that it would be difficult to make proper amendments to the articles of confederation.” [Gerry to Massachusetts Legislature, 18 October 1787][48]

- “I have been ever solicitous for an efficient federal government, conceiving that without it, we must be a divided, an unhappy people.” [Gerry to the Electors of Middlesex, 22 January 1788][49]

“Time only can determine”

Gerry and the Federal Farmer were non-committal about the constitution. Both repeatedly used the phrase only “time” can “determine” the outcome. Federal Farmer No. 1 opined that “whether it can be effected without convulsions and civil wars; whether such a change will not totally destroy the liberties of this country—time only can determine.” Federal Farmer No. 18 similarly observed, “[h]ow far the union will find it practicable to do this, time only can fully determine.”

Gerry used a substantially similar phraseology in his correspondence:

- “time must determine the fate of this production” [Gerry to John Adams, 20 Sept. 1787][50]

- “indeed as objectionable as the constitution was in my mind I should have preferred an adoption of it, to an hazard of a dissolution of the Union, but, being very apprehensive that the necessary amendments would never be obtained unless previously to a ratification I tho’t good policy directed a suspension, & time must determine whether or not I was mistaken, untill the effects of the efforts of the states for amendments could be ascertained.” [Gerry to John Wendell, 10 July 1789][51]

- “Whether the present constitution will preserve its theoretical balance, for I consider it altogether as a political experiment, if it should, what will be the effect, or if it should not, to what system it will verge, are secrets that can only be unfolded by time” [Gerry to John Wendell, 14 Sept 1789][52]

Part 6 will present additional attribution evidence linking Gerry and the Federal Farmer. Although he had reservations about doing so, Elbridge Gerry served in the first Federal Congress. As to be expected, Gerry’s speeches in Congress align with the positions of the Federal Farmer. Part 6 concludes with a discussion of “Gerry’s endgame,” the adoption of constitutional amendments, which further illustrate Gerry’s identity as the Federal Farmer.

Endnotes

[1] Farrand, 3:128.

[2] The Federal Farmer’s “style, tone and wording” align with Gerry. John P. Kaminski, “The Role of Newspapers in New York’s Debate Over the Federal Constitution,” in Stephen L. Schechter and Richard B. Bernstein, eds., New York and the Union (Albany, 1990), 286. While the exercise of enumerating Gerry’s signature “fingerprints” is imprecise, the goal is to identify elements of the Federal Farmer’s writing style that can be tested against other potential authors.

[3] It was common in the 18th century to refer to the New England as the “eastern” states/colonies, as they were both north and east of the middle and southern states.

[4] Massachusetts Constitution, Part 2, Chapter 1, Section III, Art I.

[5] Cato No. 4, New-York Journal, 8 November 1787.

[6] Brutus No. 1 (October 18), Brutus No. 3 (November 15; 2 times), and Brutus No. 4 (November 29).

[7] Brutus No. 3 (November 15).

[8] Brutus uses the phrase “people of America” nine times, while the Federal Farmer only uses it once. Thus, “people of America” can be considered a Brutus fingerprint.

[9] Billias, 153.

[10] Farrand, 1:48.

[11] Farrand, 2:57.

[12] Farrand, 1:98.

[13] We shall view the convention with proper respect—and, at the same time, that we reflect there were men of abilities and integrity in it, we must recollect how disproportionably the democratic and aristocratic parts of the community were represented – Perhaps the judicious friends and opposers of the new constitution will agree, that it is best to let it rest solely on its own merits, or be condemned for its own defects.

[14] Farrand, 2:127.

[15] Elbridge Gerry to President of Congress, 3 April 1780.

[16] Elbridge Gerry to John Adams, 10 Jan 1781.

[17] Farrand, 2:632-33.

[18] Reply to Landholder II, Farrand, 3:330.

[19] Billias, 33.

[20] Farrand, 1:48.

[21] Elbridge Gerry to Francis Dana, 6 January 1784; LDC, 21:263.

[22] Elbridge Gerry to John Adams, 14 Feb 1785.

[23] Elbridge Gerry to John Adams, 25 April 1785.

[24] Elbridge Gerry to Rufus King, 18 May 1785.

[25] Elbridge Gerry to John Adams, 30 Jan 1797.

[26] Elbridge Gerry to Thomas Jefferson, 15 Jan 1801.

[27] Farrand, 1:132.

[28] Farrand, 1:61.

[29] Elbridge Gerry to Samuel Holten, 2 April 1785 (quoted in Billias, 378).

[30] Beeman, Plain, Honest Men, 113.

[31] Billias, 154.

[32] Compare Federal Farmer No. 7 with Gerry’s speech on August 14. Farrand, 2:285.

[33] Federal Farmer No. 7 compares three types of aristocracy:

There are three kinds of aristocracy spoken of in this country—the first is a constitutional one, which does not exist in the United States in our common acceptation of the word. Montesquieu, it is true, observes that where a part of the persons in a society, for want of property, age, or moral character, are excluded any share in the government, the others, who alone are the constitutional electors and elected, form this aristocracy: this, according to him, exists in each of the United States, where a considerable number of persons, as all convicted of crimes, under age, or not possessed of certain Property, are excluded any share in the government:—the second is an aristocratic faction: a junto of unprincipled men, often distinguished for their wealth or abilities, who combine together and make their object their Private interests and aggrandizement: the existence of this description is merely accidental, but particularly to be guarded against. The third is the natural aristocracy: this term we use to designate a respectable order of men, the line between whom and the natural democracy is in some degree arbitrary; we may place men on one side of this line, which others may place on the other, and in all disputes between the few and the many, a considerable number are wavering and uncertain themselves on which side they are, or ought to be. In my idea of our natural aristocracy in the United States, I include about four or five thousand men: and among these I reckon those who have been placed in the offices of governors, of members of Congress, and state senators generally, in the principal officers of Congress, of the army and militia, the superior judges, the most eminent professional men. &c. and men of large property—the other persons and orders in the community form the natural democracy: this includes in general the yeomanry, the subordinate officers, civil and military, the fishermen, mechanics and traders, many of the merchants and professional men.

[34] Farrand, 1:474.

[35] According to Madison’s notes on June 7:

Mr. Gerry insisted that the commercial & monied interest wd. be more secure in the hands of the State Legislatures, than of the people at large. The former have more sense of character, and will be restrained by that from injustice. The people are for paper money when the Legislatures are agst. it. In Massts. the County Conventions had declared a wish for a depreciating paper that wd. sink itself. Besides, in some States there are two Branches in the Legislature, one of which is somewhat aristocratic. Farrand, 1:154-155.

[36] Farrand, 2:286.

[37] Farrand, 1:513.

[38] You will probably enquire, what Inconveniences I allude to, & the answer is, the Inconveniences of being entangled with European politics; of being the puppets of European Statesmen; of being gradually divested of our vertuous republican principles; of being a divided, influenced, & dissipated, people; of being induced to prefer the Splendor of our Court, to the Happiness of our Citizens; & finally of changing our Form of Government, established at an amazing Expence of Blood & Treasure, for a vile Aristocracy or an arbitrary Monarchy. these are the Inconveniences, or rather the deplorable Evils which I apprehend from a permanent System of Embassies, & had You seen what I have been so unfortunate as to see, after only three Years Absence from Congress, almost a total Change of political principles; had You the same Reasons for tracing those Effects to the Causes alluded to, perhaps We should not differ much in our proposals for a Remedy. Gerry to John Adams, 23 November 1783.

[39] Here I am after a six Months Session at Annapolis, on my Way to Massachusetts, & altho my Opposition to the same System in America, which you have opposed in Europe, has perhaps rendered me equally obnoxious here to the aristocratic Party, yet I assure You the Pleasure resulting from a Reflection on the Measures adopted by Congress, overballances every trifling Consideration of the loss of Friendships, which being for the most part ostensible, are generally applied as Incentives to or Rewards of Servility Baseness & Treachery, but rarely if ever of Fidelity Honor or Patriotism. Gerry to John Adams, 16 June 1784.

[40] At the Convention Gerry indicated as follows on August 23: “He warned the Convention agst pushing the experiment too far. Some people will support a plan of vigorous Government at every risk. Others of a more democratic cast will oppose it with equal determination. And a Civil war may be produced by the conflict.” Farrand, 2:388.

[41] On the final day of the Convention Gerry indicated as follows:

“He hoped he should not violate that respect in declaring on this occasion his fears that a Civil war may result from the present crisis of the U. S— In Massachusetts, particularly he saw the danger of this calamitous event— In that State there are two parties, one devoted to Democracy, the worst he thought of all political evils, the other as violent in the opposite extreme. From the collision of these in opposing and resisting the Constitution, confusion was greatly to be feared. He had thought it necessary for this & other reasons that the plan should have been proposed in a more mediating shape, in order to abate the heat and opposition of parties—” Farrand, 2:647.

[42] See also FF9, FF13, FF17.

[43] Farrand, 1:519.

[44] https://www.consource.org/document/elbridge-gerry-to-john-wendell-1789-9-14/

[45] Congressional Register, 21 July 1789.

[46] DHRC, 4:xliii.

[47] Farrand 3:45.

[48] 13 DHRC 549.

[49] Independent Gazetteer, 6 February 1789.

[50] DHRC, 4:16.

[51] Billias, 196, n. 52.

[52] https://www.consource.org/document/elbridge-gerry-to-john-wendell-1789-9-14/