The Federal Farmer’s Arguments

The Federal Farmer / Elbridge Gerry Authorship Thesis

(Uncovering the Federal Farmer – Part 6)

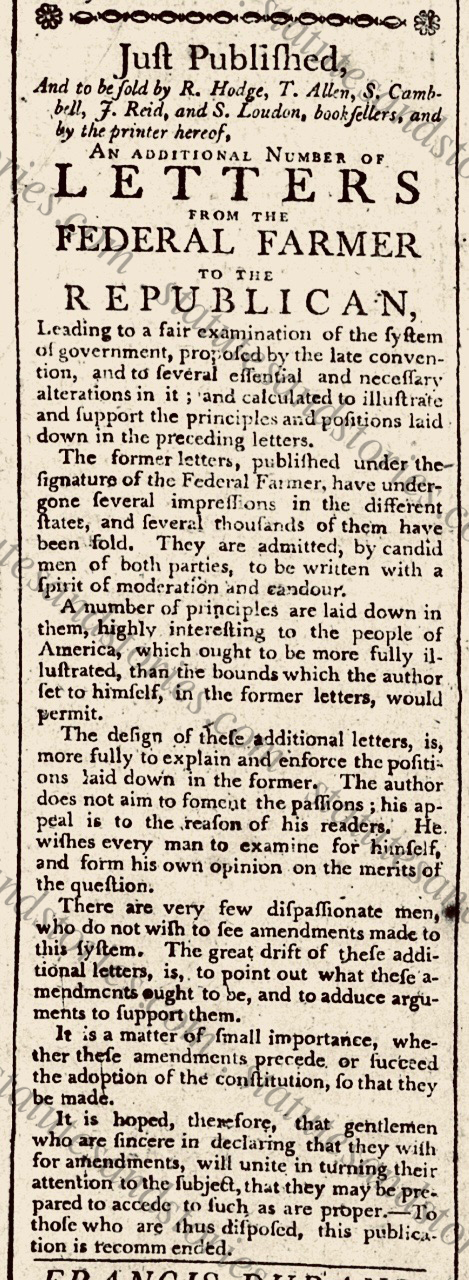

During the winter of 1787 the fate of the proposed constitution was uncertain. Federalists and Antifederalists disagreed over ratification, the need for amendments, and whether a second Constitutional Convention should be called. As the summer approached, the nation prepared for contested ratification conventions in the deeply divided states of New York and Virginia.[1] In May, the month before the eagerly anticipated New York ratification convention was scheduled to meet,[2] nearly identical advertisements began appearing in New York City newspapers.[3] Thomas Greenleaf’s New York Journal announced that a second pamphlet from the Federal Farmer was “Just Published and to be sold.” This was decidedly good news for Antifederalists, but not so for Federalists.[4]

The New York ratification convention began in mid-June 1788 and would not adjourn until July 26th. On the evening of July 4th Federalists and Antifederalists alike celebrated the nation’s birthday. As reported in the Poughkeepsie County Journal,[5] a number of respectable citizens assembled at the house of Antifederalist Mathew Patterson. Glasses were raised for thirteen toasts, starting with the anniversary of American independence. Additional toasts honored Congress, General Washington, and the late army. With the New York ratification convention still meeting in Poughkeepsie, the following toasts were also raised:

- May the Convention of this State deliberate with coolness, impartiality and wisdom, on the important business now before them.

- May the electors of the State of New-York, never give their suffrages to men or measures that may enslave them.

- Annual elections, the basis of freedom in Republican Government.

- The Federal Farmer and the Plebian.[6]

- May the genius of America ever guard her sons against tyranny.

As described by historians, the Letters of the Federal Farmer “became a primer for the Antifederalists.”[7] Indeed, several of the July 4th toasts borrowed from the Federal Farmer’s arguments, in addition to toasting the Federal Farmer himself. For example, the Federal Farmer suggested that the state conventions should “examine coolly every article, clause and word” of the proposed Constitution and adopt it “with such amendments as they shall think fit.”[8] The Federal Farmer also argued for annual elections, which not coincidentally was a consistent position held by Elbridge Gerry.[9]

This blog post, Uncovering the Federal Farmer (Part 6), is the sixth installment of a multi-part series attempting to demystify the Federal Farmer. Part 1 revealed an unpublished and undated manuscript by Elbridge Gerry which sheds new light on his identity as the Federal Farmer. Part 2 explores Gerry’s background and examines the historiography of the Federal Farmer, long believed to have been Richard Henry Lee. Part 3 provides an overview of the mounting evidence supporting John Kaminski’s attribution that Elbridge Gerry was the Federal Farmer, not Melancton Smith as commonly assumed by modern historians.

Part 4 takes a deep dive into archival evidence and the historic record summarized in Part 3. For example, the Antifederalists had difficulty getting published.[10] Yet, it turns out that Elbridge Gerry was related to New York publisher, Thomas Greenleaf. Does the fact that Gerry’s mother was a Greenleaf help explain Thomas Greenleaf’s decision to publish the Letters of the Federal Farmer and other Antifederalist works?

As set forth in Part 4 the Federal Farmer consistently grounded his arguments with examples from Massachusetts. In hindsight it should not be surprising that multiple, specific citations to substantive provisions of the Massachusetts Constitution have been uncovered in the Letters of the Federal Farmer. Part 5 identifies signature phrases used by Elbridge Gerry and the Federal Farmer, which are analogous to linguistic “fingerprints.”

Building on Part 5, Part 6 presents additional evidence in support of the Federal Farmer – Elbridge Gerry AuthorshipThesis (FEAT). In 1988 John P. Kaminski posited that “all of the positions taken by the Federal Farmer appear perfectly consistent with Gerry’s stance at the Constitutional Convention.”[11] Part 6 takes a wide-angle view of Gerry’s record. Elbridge Gerry was not a typical Antifederalist. Some of the Federal Farmer’s positions might be described as advancing “unexpected Antifederalist arguments,” which provide further evidence linking Gerry and the Federal Farmer. Part 6 demonstrates that the Federal Farmer’s underlying arguments and reasoning aligns with Gerry’s positions at the Convention, October 18th objections, and speeches during the first Federal Congress.

Part 7 continues with a discussion of “Gerry’s endgame,” the adoption of constitutional amendments, which further illustrate Gerry’s identity as the Federal Farmer. For example, neither Gerry nor the Federal Farmer wanted to rush the adoption of constitutional amendments. Rather, as a member of the first Federal Congress, Gerry supported the adoption of essential legislation necessary to establish a working federal government, before proceeding with a robust and transparent amendment process.[12]

While no single piece of evidence is alone conclusive, it is believed that the combined weight of the mutually reinforcing attribution evidence is striking. It is anticipated that independent scholarly review of the FEAT Thesis will support the conclusion that Kaminski’s attribution is now settled. In other words, the goal of this exercise is put to rest “by far the most controversial and long-lived debate”[13] over the authorship of a pseudonymous essay.

A discussion of the Federal Farmer would not be complete without a discussion of Melancton Smith. Part 8 (pending) builds on Kaminski’s suggestion that Smith was likely the Republican to whom the letters of the Federal Farmer were addressed, not the author of the Federal Farmer letters. This is not to say that Melancton Smith wasn’t busy during the ratification campaign. Smith deserves recognition as the author of Brutus and Plebeian.

Federal Farmer Advertisements

The Federal Farmer’s second pamphlet, entitled An Additional Number of Letters from the Federal Farmer (hereinafter the Federal Farmer’s “Additional Letters”), was widely advertised in the New York newspapers during the spring and summer of 1788. It is unclear who wrote the advertisements for the Additional Letters. The advertisements could have been written or co-written by Gerry, Thomas Greenleaf, or another publisher. Nevertheless, the widely published advertisements contain useful attribution evidence aligning with Elbridge Gerry.

Before exploring the Federal Farmer’s underlying arguments, it makes sense to review the claims made in the newspaper advertisements for the Additional Letters. The representations made to potential readers about the Federal Farmer help frame the author’s objectives. In particular, the newspaper advertisements highlight the Federal Farmer’s “moderation and candor,” recommended amendments, and goal “to adduce arguments to support them.” Importantly, the Federal Farmer was more concerned with the “merits of the question” and less concerned with the timing of whether amendments were adopted before or after ratification. As set forth below, the following statements support the FEAT thesis:

- “The former letters, published under the signature of the Federal Farmer have undergone several impressions in the different states, and several thousands of them have been sold. They are admitted, by candid men of both parties, to be written with a spirit of moderation and candour.”

- “The design of these additional letters, is, more fully to explain and enforce the positions laid down in the former. The author does not aim to foment the passions; his appeal is to the reason of his readers. He wishes every man to examine for himself, and form his own opinion on the merits of the question.”

- “There are very few dispassionate men, who do not wish to see amendments made to this system. The great drift of these additional letters, is, to point out what these amendments ought to be, and to adduce arguments to support them.”

- “It is a matter of small importance, whether these amendments precede or succeed the adoption of the constitution, so that they be made.”

- “It is hoped, therefore, that gentlemen who are sincere in declaring that they wish for amendments, will unite in turning their attention to the subject, that they may be prepared to accede to such as are proper.—To those who are thus disposed, this publication is recommended.”

In addition to newspaper advertisements, the Additional Letters began with a three paragraph advertisement dated January 30, 1788.[14] Among other things, the introductory advertisement printed in the pamphlet highlighted the Federal Farmer’s disinclination to foment passions, “appeal to reason,” and admission that “he is well acquainted with the members of the convention…as respectable a body of men as America, probably, ever will see assembled.” As discussed in Parts 4 and 5, these statements contain autobiographical clues and stylistic fingerprints connecting Gerry and the Federal Farmer. Accordingly, the following three paragraph advertisement supports the FEAT thesis:

Four editions, (and several thousands) of the pamphlets entitled the Federal Farmer, being in a few months printed and sold in the several states; and as they appear to be much esteemed by one party, on the great question, and, by the other, generally allowed to possess merit; and as they contain positions highly interesting, which ought to be fully illustrated, an additional number of letters have been written.

The subject before the public is interesting, and ought to receive a candid and full investigation. These letters are not calculated to foment the passions; they appeal to reason; they are written in a plain stile, with all the perspicuity and brevity that can be expected in writing on a subject so new, so intricate and extensive; and they have this peculiar excellency, that they lead people to examine and think for themselves, in an affair of the last importance to them.

As to any attempts to injure the members of the convention, or any other characters whatever, the writer has no disposition to do it. Whoever will examine his letters, will perceive he is well acquainted with the members of the convention, the characters, parties, and politics of the country; and, on the whole, says, the convention was as respectable a body of men as America, probably, ever will see assembled: at the same time they will perceive, that he saw unwarrantable attempts, among designing ardent men without doors, to impose upon a free people, by a parade of names, that in the hurry of affairs defects in the system might escape their observation. Whoever reflects coolly upon the conduct of many individuals, when the constitution first appeared, will perceive, that it was the duty of men, who saw the pernicious tendency of such conduct, in a decent manner, to disapprove it, and to endeavour to induce the people to decide upon the all-important subject before them, by its own intrinsic merits and faults.

Moderation

Both Elbridge Gerry and the Federal Farmer were moderate Antifederalists. During the early days of the Constitutional Convention, Gerry opined that “[t]he evils we experience flow from the excess of democracy.” He acknowledged that he had been “too republican heretofore: he was still however republican, but had been taught by experience the danger of the levilling spirit.”[15] Gerry likewise described himself as “principled as ever against aristocracy and monarchy.” Further illustrating his moderation, Gerry stated that, “[h]e was not disposed to run into extremes.”[16]

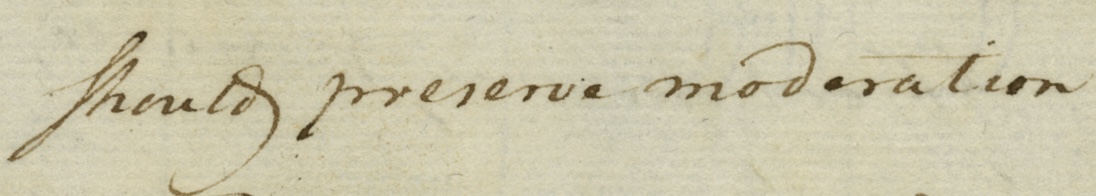

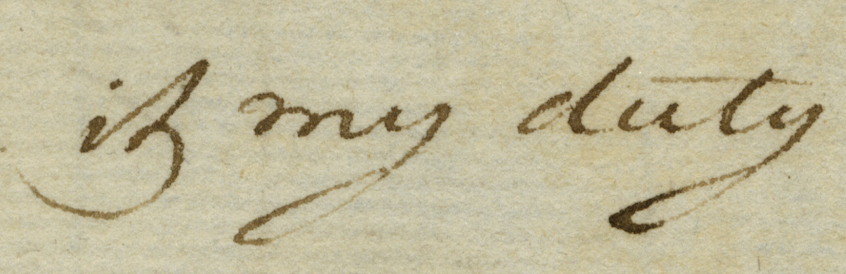

In his October 18 letter to the Massachusetts legislature Gerry agreed that if the Constitution were ultimately ratified over his objections it would be his duty to support it. Gerry explained that “I shall think it my duty as a citizen of Massachusetts to support that which shall be finally adopted, sincerely hoping it will secure the liberty and happiness of America.” He emphasized the importance for all parties to “preserve moderation.”[17]

Gerry’s statements during and after the Convention align perfectly with the advertisements for the Federal Farmer. The newspaper advertisements for the Additional Letters emphasized that they were written “with a spirit of moderation and candor.” Likewise, the newspaper ads made clear that the author did “not aim to foment the passion; his appeal is to the reason of his readers. He wishes every man to examine for himself and form his own opinion on the merits of the question.” The same sentiment was expressed in the introductory advertisement printed in the Federal Farmer pamphlet.

This moderation is repeatedly evident in both Federal Farmer pamphlets, particularly Federal Farmer Nos. 3, 5 and 6 as follows:

- “I wish the system adopted with a few alterations; but those, in my mind, are essential ones; if adopted without, every good citizen will acquiesce, though I shall consider the duration of our governments, and the liberties of this people, very much dependent on the administration of the general government.” (FF3)

- “There are, however, in my opinion, many good things in the proposed system.” (FF5)

- “…on carefully examining them on both sides, I find much less reason for changing my sentiments, respecting the good and defective parts of the system proposed than I expected — The opposers, as well as the advocates of it, confirm me in my opinion, that this system affords, all circumstances considered, a better basis to build upon than the confederation.” (FF6)

For decades scholars have recognized that the Federal Farmer was a “moderate” Antifederalist who “avoided the shrill alarmism of other Anti-Federalists.”[18] In fact Gordon Wood relied on this characterization as one of the grounds to dispute the longstanding attribution that Richard Henry Lee was the Federal Farmer. Wood explained that the Federal Farmer’s “moderation, reasonableness and tentativeness” contrasted with Lee’s “more emotional language,” repeated use of rhetorical questions, exclamatory statements, and charged phrases.[19]

For historian Jack Rakove, the Federal Farmer’s moderation was evidence that Melancton Smith, a “moderate Anti-Federalist,” was the Federal Farmer.[20] Yet, as pointed out by John Kaminski, Melancton Smith only moderated his stance at the New York ratification convention after news arrive that Virginia had ratified the Constitution.[21]

Historians have likewise long known that Gerry was a “moderate” from the “well-to-do wing of Anti-Federalism.”[22]George A. Billias, Gerry’s biographer, absolutely agrees with this understanding of Gerry’s moderation. “Gerry’s stance can best be described as a balanced one – a middle-of-the-road nationalist who would strengthen the central government but, at the same time, would insist upon maintaining certain ‘federal features.’ ”[23]

Gerry’s moderation was also evident as Congress considered amendments in June of 1789. Gerry explained that he was not a “blind admirer” of the Constitution, but was not “so blind as to not see its beauties”:

I say, sir, I wish as early a day as possible may be assigned for taking up this business, in order to prevent the necessity which the states may think themselves under of calling a new convention. For I am not, sir, one of those blind admirers of this system, who think it all perfection; nor am I so blind as not to see its beauties. The truth is, it partakes of humanity; in it is blended virtue and vice, errors and excellence. But I think, if it is referred to a new convention, we run the risk of losing some of its best properties; this is a case I never wish to see. Whatever might have been my sentiments of the ratification of the constitution without amendments, my sense now is, that the salvation of America depends upon the establishment of this government, whether amended or not. If the constitution which is now ratified should not be supported, I despair of ever having a government of these United States.[24]

Admittedly, the moderation of Gerry and the Federal Farmer by itself doesn’t prove anything. Yet, it is useful to lay this predicate for the FEAT thesis.

Amending not annihilating/destroying

In Gerry’s very first speech on May 30, 1787, he questioned whether the Constitutional Convention had the authority[25]to effectively “annihilate the confederation.”[26] Federal Farmer No. 1 supported “amending,” not “destroying” the confederation. Gerry’s October 18 letter to the Massachusetts legislature noted that the Convention was called for the “sole and express purpose of revising the Articles.” Luther Martin likewise confirmed that “Mr. Gerry’s opposition proceeded from a conviction that the Constitution, if adopted, would terminate in the destruction of the States….”[27]

Gerry’s thinking both during and after the Constitutional Convention directly aligns with Federal Farmer No. 1:

The idea of destroying ultimately, the state government, and forming one consolidated system, could not have been admitted—a convention, therefore, merely for vesting in congress power to regulate trade was proposed. This was pleasing to the commercial towns; and the landed people had little or no concern about it. September, 1786, a few men from the middle states met at Annapolis, and hastily proposed a convention to be held in May, 1787, for the purpose, generally, of amending the confederation–this was done before the delegates of Massachusetts, and of the other states arrived–still not a word was said about destroying the old constitution, and making a new one. The states still unsuspecting, and not aware that they were passing the Rubicon, appointed members to the new convention, for the sole and express purpose of revising and amending the confederation–and, probably, not one man in ten thousand in the United States, till within these ten or twelve days, had an idea that the old ship was to be destroyed, and be put to the alternative of embarking in the new ship presented, or of being left in danger of sinking. The States, I believe, universally supposed the convention would report alterations in the confederation, which would pass an examination in congress, and after being agreed to there, would be confirmed by all the legislatures, or be rejected.

Multiple sources confirm that Gerry repeatedly expressed the concern that the proposed Constitution ran the risk of annihilating/destroying the state governments. In addition to Gerry’s May 30 speech, Yates, Paterson and Martin similarly quote Gerry describing the risk of annihilating the states:

- “Gerry rather supposes that the national legislators ought to be sworn to preserve the state constitutions, as they will run the greatest risk to be annihilated….” Farrand, 1:207 (Robert Yates quoting Gerry on June 12)

- “…the present plan…tends to annihilate the state-governments.” Farrand, 1:555 (William Paterson quoting Gerry on July 7).

- “when they [Gerry & Mason] viewed it charged with such powers, as would destroy all State governments, their own as well as the rest, — when they saw a president so constituted as to differ from a monarch scarcely but in name, and having it in his power to become such in reality when he pleased; they being republicans and fœderalists, as far as an attachment to their own States would permit them, they warmly and zealously opposed those parts of the system.” Farrand, 3:181 (Martin’s Genuine Information dated December 28, 1787).

Consolidation and terminology

Both Gerry and the Federal Farmer were concerned about the dangers of “consolidation” of the federal system under the Articles of Confederation into a national government. In his May 30 Convention speech Gerry questioned the Convention’s authority to replace the “federal” government with a consolidated “national” government. On July 7 Gerry appears to have sought compromise involving consolidation, short of a “national plan.”[28] As described by Gouverneur Morris, “It had been sd. (by Mr. Gerry) that the new Governt. would be partly national, partly federal.”[29] Yet, in his October 18 letter to the Massachusetts legislature, Gerry observed that the proposed Constitution had “few if any federal features, but is rather a system of national government.”

Federal Farmer No. 1 likewise tracks Gerry’s thinking. The Federal Farmer distinguished between three different forms of “free government”: 1) “distinct republics connected under a federal head,” the existing “federal plan” under the Articles of Confederation, 2) “complete consolidation” as proposed by the Convention, or 3) “partial consolidation” preferred by the Federal Farmer.

- “It appears to be a plan retaining some federal features; but to be the first important step, and to aim strongly to one consolidated government of the United States.”

- “The plan proposed appears to be partly federal, but principally however, calculated ultimately to make the states one consolidated government”;

- “it is clearly designed to make us one consolidated government”;

- “The idea of destroying, ultimately, the state government, and forming one consolidated system could not have been admitted.”

- “The third plan, or partial consolidation, is, in my opinion, the only one that can secure the freedom and happiness of this people.”

As described by Gordon Wood, the “problem of consolidation and the threatened destruction of the states” was critically important for the Federal Farmer.[30] The fact that Richard Henry Lee did not express similar concerns was evidence that Lee was not the Federal Farmer. When John Kaminski theorized that Gerry was the Federal Farmer, he similarly pointed to the problem of consolidation: Gerry objected that the Constitution had “few, if any federal features” and the Federal Farmer worried that the Constitution retained “some federal features,” but was the first important step toward “consolidated government.”[31]

The problem of consolidation also implicated an issue of terminology for the Federalists and Antifederalists. Both Gerry and the Federal Farmer agreed with the same Antifederalist definition of the term “Federalist.” They both criticized the way that the Federalists co-opted the term.

Federal Farmer No. 6 discussed terminology as it evolved:

- “Some of the advocates are only pretended federalists; in fact they wish for an abolition of the state governments.”

- “Some of them I believe to be honest federalists, who wish to preserve substantially the state governments united under an efficient federal head”

- “Some of the opposers also are only pretended federalists, who want no federal government, or one merely advisory.”

- “Some of them are the true federalists, their object, perhaps, more clearly seen, is the same with that of the honest federalists; and some of them, probably, have no distinct object.”

- “We might as well call the advocates and opposers tories and whigs, or any thing else, as federalists and anti-federalists.”

In a letter to his friend following the ratification campaign, Gerry summarized that, “[a] federalist I always was, but not in their sense of the word.”[32] As described by Gerry’s biographer:

In the state ratification conventions, Gerry observed that “antifederalists” like him claimed that the new form of government had “consolidated the Union,” that is created a central government with the power to coerce citizens and states. The term “anti-federalist,” Gerry noted, was totally inaccurate; it implied exactly the opposite of what he stood for.[33]

In the First Federal Congress Gerry humorously made the same point. “[T]he federalists were for ratifying the constitution as it stood, and the others not until amendments were made. Their names then ought not to have been distinguished by federalists and antifederalists, but rats and antirats.” Gerry explained that “those who were called antifederalists at the time complained that they had injustice done them by the title, because they were in favor of a federal government, and the others in favor of a national one.”[34]

Underlying arguments of the Federal Farmer

The goal of Part 6 is to identify evidence that the Federal Farmer’s underlying arguments and reasoning align with Gerry’s positions and objections at the Convention, his October 18th written objections to the Massachusetts legislature, and speeches during the first Federal Congress. Admittedly, distinguishing between Gerry’s “fingerprints,” “objections,” and underlying “arguments” is necessarily arbitrary. Nevertheless, due to the sheer volume of evidence, these distinctions are useful analytical and organizational tools.

Part 6 builds on the work of Part 5, which identified the signature phrases used by Gerry and the Federal Farmer, which are analogous to linguistic fingerprints. The label linguistic fingerprint is applied to relatively unique, signature phrases repeatedly used by Gerry and the Federal Farmer.

By contrast, a supporting “argument” made by the Federal Farmer would be of less evidentiary value to the extent that other Antifederalists make similar arguments. The category of “unexpected Antifederalist arguments” is viewed as particularly relevant for the FEAT thesis. Part 6 discusses below dozens of supporting “arguments” made by the Federal Farmer, but only a handful of “unexpected Antifederalist arguments.” The “unexpected” Antifederalist arguments, or minority Antifederalist views, illustrate the daylight between the Federal Farmer/Gerry compared to other Antifederalist colleagues.

Danger of the levellers/levilling spirit and aristocratic reactionaries

Gerry and Federal Farmer both warned of the danger of the “levellers”/“levilling spirit.” Gerry was from Massachusetts, the site of Shays’ Rebellion. In his second speech at the Convention Gerry opined that “[t]he evils we experience flow from the excess of democracy.” He was almost certainly referring to Shays’ Rebellion. Gerry indicated that “[t]he people do not want [i.e., lack] virtue; but are the dupes of pretended patriots.” Gerry elaborated that “[i]n Massts. it has been fully confirmed by experience that they are daily misled into the most baneful measures and opinions by the false reports circulated by designing men, and which no one on the spot can refute.” Gerry acknowledged that he had been “too republican heretofore: he was still however republican, but had been taught by experience the danger of the levilling spirit.” [35]

The Federal Farmer was also critical of the “levellers.” Federal Farmer No. 5 warned of “two fires” set by “two very unprincipled parties.” According to the Federal Farmer, “[o]ne party is composed of little insurgents, men in debt, who want no law, and who want a share of the property of others; these are called levellers, Shayites, &c.” Providing background, the Federal Farmer explained that, “[i]n 1786, the little insurgents, the levellers, came forth, invaded the rights of others, and attempted to establish governments according to their wills.”

At the other extreme, Federal Farmer No. 1 explained, were men “unfriendly to republican equality.” Federal Farmer No. 5 elaborated that this reactionary, aristocratic party was “composed of a few, but more dangerous men, with their servile dependents” who “avariciously grasp at all power and property….” Based on their “evident dislike to free and equal government,” the Federal Farmer No. 5 warned that this second group “will go systematically to work to change, essentially, the forms of government in this country; these are called aristocrats, morrisites etc. etc.”[36] The letters of the Federal Farmer were addressed to the silent majority in the middle. “Between these two parties is the weight of the community: the men of middling property, men not in debt on the one hand, and men, on the other, content with republican governments, and not aiming at immense fortunes, offices, and power.”[37]

Need to preserve the union / “critical” situation but “no immediate danger”

During the Convention Gerry recognized the need for action to preserve the union. He feared that the Confederation was “dissolving.” Gerry advised that the “fate of the union will be decided by the Convention.”[38] The Federal Farmer Nos. 1 and 6 agreed that “our situation is critical.”

While the Federal Farmer recognized that the situation was “critical, “he cautioned against acting in haste:

- “I know our situation is critical, and it behoves us to make the best of it.” (FF1)

- “If we remain cool and temperate, we are in no immediate danger of any commotions” (FF1)

- The Confederation is “in many respects…inadequate to the exigencies of the union” (FF1)

- “I presume the enlightened and substantial part will give any constitution presented for their adoption a candid and thorough examination; and silence those designing or empty men, who weakly and rashly attempt to precipitate the adoption of a system of so much importance.” (FF1)

- “Our situation is critical, and we have but our choice of evils — We may hazard much by adopting the constitution in its present form — we may hazard more by rejecting it wholly — we may hazard much by long contending about amendments prior to the adoption. The greatest political evils that can befal us, are discords and civil wars — the greatest blessings we can wish for, are peace, union, and industry, under a mild, free, and steady government.” (FF6)

Gerry shared similar concerns about the fate of the union during and after the Constitutional Convention:

- “The fate of the Union will be decided by the Convention. If they do not agree on something, few delegates will probably be appointed to Congs. If they do Congs. will probably be kept up till the new System should be adopted. He lamented that instead of coming here like a band of brothers, belonging to the same family, we seemed to have brought with us the spirit of political negotiators.” (Gerry at Convention on 6/29)

- “If no compromise should take place what will be the consequence. A secession he foresaw would take place; for some gentlemen seem decided on it: two different plans will be proposed; and the result no man could foresee. If we do not come to some agreement among ourselves some foreign sword will probably do the work for us.” (Gerry at Convention on 7/5)

- “[At the Convention] I acquiesced in it, being fully convinced that to preserve the union, an efficient government was indispensibly necessary; and that it would be difficult to make proper amendments to the articles of confederation.” (Gerry’s letter to Massachusetts legislature dated 18 October 1787)

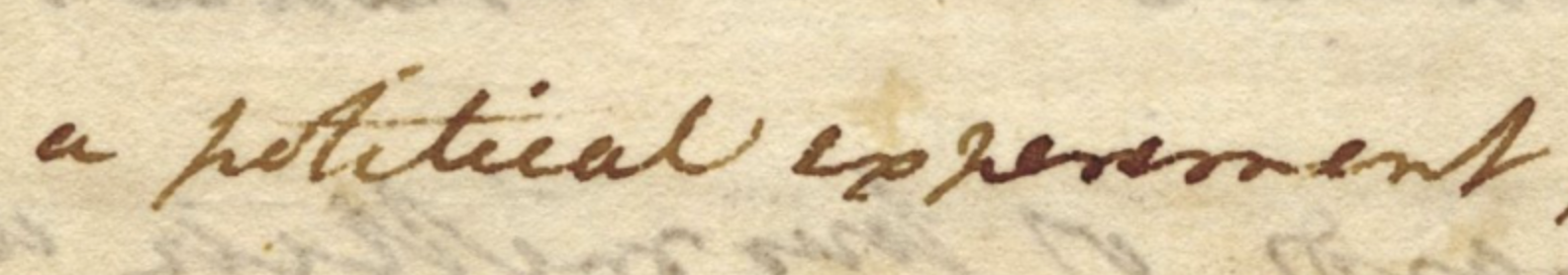

Implicit” adoption v. political “experiment”

Both Gerry and the Federal Farmer criticized the Federalists for seeking the “implicit” adoption of the Constitution based merely on the names of “incontestible authorities” / “respected members” who framed it. Rather, Gerry and the Federal Farmer viewed the Constitution as a political experiment which should not be pushed too far too quickly.

In his October 18 letter to the Massachusetts legislature Gerry opposed placing “implicit confidence” in the framers of the Constitution. Gerry observed that however respectable the framers of the Constitution were, even the “greatest men” were not infallible:

It may be urged by some, that an implicit confidence should be placed in the Convention: But, however respectable members may be who signed the Constitution, it must be admitted, that a free people are the proper Guardians of their rights & liberties—that the greatest men may err—& that their errors are sometimes, of the greatest magnitude.

The Federal Farmer aligns with Gerry’s thinking and then some. Federal Farmer No. 6 was published in May, more than six months after Gerry’s October 18 letter. During the intervening period, at least one circumstance had changed: Mason, Gerry and Lee had been subjected to “indecent virulence,” as noted by the Federal Farmer who opposed treating the names of the framers as “incontestible authorities for the implicit adoption of the system”:

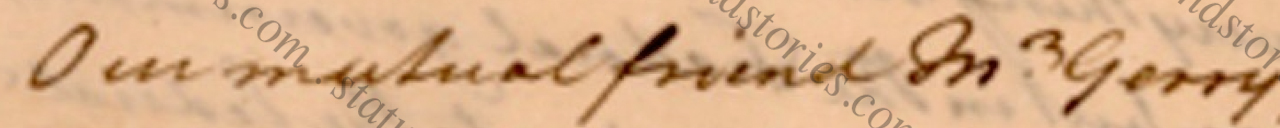

Had the advocates left the constitution, as they ought to have done, to be adopted or rejected on account of its own merits or imperfections, I do not believe the gentlemen who framed it would ever have been even alluded to in the contest by the opposers. Instead of this, the ardent advocates begun by quoting names as incontestible authorities for the implicit adoption of the system, without any examination—treated all who opposed it as friends of anarchy; and with an indecent virulence addressed M—n G—y, L—e, and almost every man of weight they could find in the opposition by name.

To the contrary, both Gerry and the Federal Farmer suggested that the Constitution ought to be treated as an “untried” “mere experiment” in government and thus the saftest course was to proceed “cautiously”:

- “But it is asked how shall we remedy the evil, so as to complete and perpetuate the temple of equal laws and equal liberty? Perhaps we never can do it. Possibly we never may be able to do it in this immense country, under any one system of laws however modified: nevertheless, at present, I think the experiment worth a making. I feel an aversion to the disunion of the states, and to separate confederacies: the states have fought and bled in a common cause, and great dangers too may attend these confederacies. I think the system proposed capable of very considerable degrees of perfection, if we pursue first principles.” (FF9)

- “The system proposed is untried: candid advocates and opposers admit, that it is, in a degree, a mere experiment, and that its organization is weak and imperfect: surely then, the safe ground is cautiously to vest power in it, and when we are sure we have given enough for ordinary exigencies, to be extremely careful how we delegate powers, which, in common cases, must necessarily be useless or abused, and of very uncertain effect in uncommon ones.” (FF17)

Gerry’s speeches during the Convention and subsequent correspondence as a member of Congress fully align with the Federal Farmer’s admonition to proceed cautiously with the national political experiment:

- “Mr. Gerry favored it. The novelty & difficulty of the experiment requires periodical revision.” (June 5)[39]

- “Mr. Gerry: Let us at once destroy the State Govts have an Executive for life or hereditary, and a proper Senate, and then there would be some consistency in giving full powers to the Genl Govt. but as the States are not to be abolished, he wondered at the attempts that were made to give powers inconsistent with their existence. He warned the Convention agst pushing the experiment too far. Some people will support a plan of vigorous Government at every risk. Others of a more democratic cast will oppose it with equal determination. And a Civil war may be produced by the conflict.”[40] (Aug 23)

- “Whether the present constitution will preserve its theoretical balance, for I consider it altogether as a political experiment, if it should, what will be the effect, or if it should not, to what system it will verge, are secrets that can only be unfolded by time: as to the amendments proposed by Congress, they will not affect those questions or serve any other purposes than to reconcile those who had no adequate idea of the essential defects of the Constitution.”[41]

Alignment of Gerry’s substantive positions during the Convention and the Federal Farmer

The substantive positions taken by Gerry during the Constitutional Convention fully align with the arguments made by the Federal Farmer. The preceding discussion involved procedural or background views by Gerry and the Federal Farmer (the “critical” situation, concern about the Levellers, the need for experimentation and caution). The following discussion involves the substantive arguments made by Gerry and the Federal Farmer. The FEAT Thesis argues that the lack of daylight between Gerry’s positions during the Convention and the letters of the Federal Farmer is strong attribution evidence. Kaminski made this observation in 1988.[42] All of Gerry’s oral “objections” on September 12 and written objections of October 18 fully align with the positions of the Federal Farmer.

Copied below are Gerry’s objections raised on September 15 at the Convention, which all align with the positions of the Federal Farmer. Click here (pending) for a link to a spreadsheet identifying all of Gerry’s September 15 objections, with cross references to the Federal Farmer letters and Gerry’s speeches at the Convention:

| Gerry’s 9/15/1787 Objections to Convention |

| 1. the duration and re-eligibilty of the Senate |

| 2. the power of the House of Representatives to conceal their journals |

| 3. the power of Congress over the places of election |

| 4. the unlimited power of Congress over their own compensations |

| 5. Massachusetts has not a due share of Representatives allotted to her |

| 6. 3/5 of the Blacks are to be represented as if they were freemen |

| 7. Under the power over commerce, monopolies may be established |

| 8. the vice president being made head of the Senate |

| He could however he said get over all these, if the rights of the Citizens were not rendered insecure by: |

| 1. the general power of the Legislature to make what laws they may please to call necessary and proper |

| 2. raise armies and money without limit |

| 3. to establish a tribunal without juries, which will be a Star-chamber as to Civil cases. |

Copied below are Gerry’s October 18 objections to the Massachusetts legislature, which all align with the Federal Farmer. Click here (pending) for a link to a spreadsheet identifying all of Gerry’s written objections on October 18, with cross references to the Federal Farmer letters and Gerry’s speeches at the Convention:

| Gerry’s 10/18/1787 Objections to MA Legislature |

| “liberties of America were not secured” |

| “no adequate provision for a representation of the people” |

| “no security for the right of election” |

| “some of the powers of the Legislature are ambiguous, and other indefinite and dangerous” |

| “the Executive is blended with and will have undue influence over the Legislature” |

| “the judicial department will be oppressive” |

| treaties can be formed with 2/3 “of a quorum” of the Senate |

| “the system is without the security of a bill of rights” |

| The Constitution “has few if any federal features, but is rather a system of national government” |

In addition to Gerry’s formal objections above, the following list enumerates Gerry’s underlying positions at the Constitutional Convention. As set forth below, Gerry’s positions and substantive arguments at the Convention align with the positions of the Federal Farmer:

- Gerry[43] and the Federal Farmer[44] supported “per capita” voting in the Senate.

- Gerry[45] and the Federal Farmer[46] wanted to protect the right of trial by jury.

- Gerry[47] and the Federal Farmer[48] were critical of standing armies.[49]

- Gerry[50] and the Federal Farmer[51] believed in military subordination civilian authority.

- Gerry[52] and the Federal Farmer[53] wanted the House to solely hold the purse strings.

- Gerry[54] and the Federal Farmer[55] supported the prohibition on bills of attainder and ex post facto laws.

- Gerry[56] and the Federal Farmer[57] supported letters of marque and reprisal.

- Gerry[58] and the Federal Farmer[59] disagreed with the re-eligibility of the President for re-election.

- Gerry[60] and the Federal Farmer[61] favored impeachment.

- Gerry[62] and the Federal Farmer[63] wanted oaths to be taken to the system as a whole, not merely the new federal government.

- Gerry[64] and the Federal Farmer[65] were worried about the lack of constitutional limits on the Senate’s treaty-making power.

- Gerry[66] and the Federal Farmer[67] preferred the creation of an Executive Council.

- Gerry[68] and the Federal Farmer[69] expressed anti-slavery views.

- Gerry[70] and the Federal Farmer[71] argued that unanimity should be required to amend the Articles.

- Gerry[72] and the Federal Farmer[73] were distrustful of hereditary honors and the Cincinnati.

Unexpected Antifederalist arguments

While the arguments by the Federal Farmer were generally embraced by other Antifederalists, this was not always the case. Instances where Gerry and the Federal Farmer diverged from other Antifederalists are particularly instructive. Examples of daylight between the Federal Farmer/Gerry and other Antifederalists, include support for per capita voting in the Senate, support for equal state representation in the Senate (which was generally only favored by Antifederalists from small states), and relative moderation by the Federal Farmer/Gerry compared to other Antifederalists. Moreover, both Gerry and the Federal Farmer supported ratification with amendments rather than outright rejection of the Constitution and/or a second convention.

Senate design & per capita voting

Unlike other Antifederalists, the Federal Farmer did not criticize per capita voting in the Senate. Indeed, allowing Senators to vote individually was proposed by Gerry during the Constitutional Convention. Based on his experience in the Confederation Congress, Gerry reasoned that individual voting in the Senate would “prevent delays” and would facilitate a national spirit to the Senate. Madison’s Convention notes on July 14 indicate that Gerry “favored the reconsideration with a view not of destroying the equality of votes; but of providing that the States should vote per capita, which he said would prevent the delays & inconveniences that had been experienced in Congs. and would give a national aspect & Spirit to the management of business.” Sherman “had no objection to the members in the 2d b. voting per capita, as had been suggested by (Mr. Gerry).” [74]

Federal Farmer No. 11 described the design of the Senate, but did not criticize individual voting or the equal representation of all states pursuant to the “Great Compromise”:

The senate is an assembly of 26 members, two from each state, though the senators are apportioned on the federal plan, they will vote individually: they represent the states, as bodies politic, sovereign to certain purposes: the states being sovereign and independent, are all considered equal, each with the other in the senate. In this we are governed solely by the ideal equalities of sovereignties: the federal and state governments forming one whole, and the state governments an essential part. which ought always to be kept distinctly in view, and preserved: I feel more disposed, on reflection, to acquiesce in making them the basis of the senate, and thereby to make it the interest and duty of the senators to preserve distinct, and to perpetuate the respective sovereignties they shall represent.

It is noteworthy that Gerry chaired the first Committee of Eleven during the Convention that grappled with the bitterly contested issue of representation. As such he fully understood how difficult it was for the Convention (and his committee) to resolve this matter. Seeking compromise, Gerry reported that the issue of Senate representation was “so serious as to threaten dissolution of the Convention.” Moreover, Gerry admitted that he had “very material objections” to his own committee’s report, but reasoned that, “if we do not come to some agreement among ourselves some foreign sword will probably do the work for us.” [75]

Arguably Gerry helped save the Constitutional Convention from collapse – twice. According to Billias:

Gerry had helped to save the Convention from possible disaster twice within two weeks. First, his committee had prepared the compromise itself. Secondly, his personal vote along with that of Strong prevented Massachusetts from rejecting the report. Gerry and Strong voted yea, and King and Gorham nay. With the Massachusetts delegation divided, its vote did not count. If Massachusetts had voted in the negative, the report would not have been accepted. It is entirely possible that the Convention might have collapsed at this stage.[76]

The Federal Farmer’s position on the design of the Senate and per capita voting by Senators put him at odds with other Antifederalists. This is thus an example of an unexpected/minority Antifederalist position by the Federal Farmer which aligns with Gerry. For example, both Luther Martin and the Antifederalist writer, “A Countryman from Duchess County” (Hugh Hughes), took issue with per capita voting in the Senate. According to Martin, per capita voting departed “from the idea of the States being represented in the 2d. branch.”[77]

In general, A Countryman praised the Federal Farmer. A Countryman No. VI observed that, “[t]hough I can not subscribe to the whole of the Foederal Farmer; yet, I think he has great merit, and well deserves the thanks of his country.” Contrasting the present confederation with a “plan of consolidation,” A Countryman VI argued that per capita voting in the Senate undermined the confederation. According to A Countryman VI, “…the present confederation, which is a union of the states, not a consolidation, all the delegates, from a state, have but one vote, and in the state senate, which is on the plan of consolidation, each senator has a vote.” Expositor II made the same point, that the design of the Senate promoted consolidation at the expense of the confederation.[78]

The well-respected Antifederalist Brutus often aligned with the Federal Farmer. Yet, Brutus III disagreed with state equality in the Senate. As was common for large-state Antifederalists, Brutus argued that representation in the Senate should be based on population, according to “every principle of equality and propriety”:

“On every principle of equality, and propriety, representation in a government should be in exact proportion to the numbers, or the aids afford by the persons represented. How unreasonable, and unjust then is it, that Delaware should have a representation in the senate, equal to Massachusetts, or Virginia? The latter of which contains ten times her numbers, and is to contribute to the aid of the general government in that proportion? ”[79]

The Federal Farmer’s unexpected Antifederalist positions on equal representation in the Senate and per capita voting by Senators are particularly useful attribution evidence which aligns with Elbridge Gerry, while excluding more ardent Antifederalists.

Duty of good citizens to acquiesce

As previously discussed, the Federal Farmer is universally characterized as a moderate Antifederalist. Among other things, ardent Antifederalists disagreed with the Federal Farmer’s willingness to abide by the result of the state ratification conventions. Federal Farmer No. 3 wrote that, “I wish the system adopted with a few alterations; but those, in my mind, are essential ones; if adopted without, every good citizen will acquiesce.” Federal Farmer No. 5 acknowledged that “[t]here are, however, in my opinion, many good things in the proposed system.” Federal Farmer No. 6 admitted that after “carefully examining them on both sides” the proposed Constitution was, “all circumstances considered, a better basis to build upon than the confederation.” While advocating for amendments, Federal Farmer No. 5 conceded that, “[i]f these conventions, after examining the system, adopt it. I shall be perfectly satisfied, and wish to see men make the administration of the government an equal blessing to all orders of men.”

These statements perfectly align with Gerry’s October 18 letter to the Massachusetts legislature:

I shall think it my duty as a citizen of Massachusetts to support that which shall be finally adopted, sincerely hoping it will secure the liberty and happiness of America…If those who are in favour of the Constitution, as well as those who are against it, should preserve moderation, their discussions may afford much information and finally direct to an happy issue.

The Antifederalists, A Countryman VI, took issue with the willingness of the Federal Farmer to acquiesce:

Now, if this be truly the gentleman’s meaning, and I can not, as I said above, at present, fairly put any other on it—I must deny his position. Nay, does not he, himself, tacitly deny it. when he says, that the alterations which he wished made ‘‘are essential ones?” For, if they are really essential, according to the true sense of the word, will it not be rather difficult to prove, that it is the duty of a good citizen to acquiesce, in the manner represented, in what is essentially wrong?[80]

A Countryman No. VI replied that it was “an indispensable duty of every good citizen, good and bad, not to acquiesce…” Similarly, A Countryman disagreed that state legislatures should abide by the Constitutional Convention’s request for state ratification conventions. For example, A Countryman No. I wanted to treat the proposed Constitution as a nullity: “Perhaps you may next enquire what can be done?—If you should, I will tell you, on Condition that you pardon the Anticipation, the Legislature may, and with the greatest Propriety, as its Delegate has exceeded his Powers, or rejected them, consider all that he has done as a Nullity.— Would not this be a useful Lesson for Usurpers?” A Countryman No. IV emphasized that, “I cannot admit to be binding on the legislature, in any manner whatever, even had the late convention really offered a good constitution.”

While Brutus was not as extreme as A Countryman, Brutus and other more ardent Antifederalists argued that the proposed Constitution was fundamentally defective. As will be discussed in Part 8 (pending), this is useful evidence that Melancton Smith was not the author of the Federal Farmer. While the Federal Farmer and Gerry advocated for amendments, they nevertheless deferred to the judgment of state ratification conventions. By contrast, Brutus I (Melancton Smith) argued that the proposed Constitution should be rejected outright:

Though I am of opinion, that it is a sufficient objection to this government, to reject it, that it creates the whole union into one government, [un]der the form of a republic, yet if this objection was obviated, there are exceptions to it, which are so material and fundamental, that they ought to determine every man, who is a friend to the liberty and happiness of mankind, not to adopt it. ⟨ beg the candid and dispassionate attention of my countrymen while I state these objections—they are such as have obtruded themselves upon my mind upon a careful attention to the matter, and such as I sincerely believe are well founded. There are many objections, of small moment, of which I shall take no notice—perfection is not to be expected in any thing that is the production of man—and if I did not in my conscience believe that this scheme was defective in the fundamental principles—in the foundation upon which a free and equal government must rest—I would hold my peace.

As described by Pauline Maier, “Brutus found the Constitution flawed in its ‘fundamental principles’ and advocated its rejection, while the Federal Farmer said the proposed Constitution included ‘many good things’ as well as ‘many important defects,’ and that ‘with several alternations’ it could create ‘a tolerably good’ federal system.” During the New York ratification convention, Melancton Smith moved for conditional ratification, including the stipulation that New York could withdraw from the Union if Congress did not call a second convention. At no time, however, did the Federal Farmer advocate for such measures. Moreover, Smith’s motions and conciliation only occurred after news arrived that Virginia had ratified.[81]

It is also useful to compare the Federal Farmer’s conciliatory position with A Columbian Patriot, who boldly issued a call for a new general convention after Massachusetts voted to ratify.[82] In an ironic twist of fate, many of his contemporaries wrongly assumed that Gerry was the author of A Columbian Patriot, which was written by Gerry’s friend, Mercy Otis Warren.[83]

Miscellaneous Attribution Arguments

Set forth below are a handful of additional attribution arguments which admittedly are only marginally helpful. Nevertheless, the FEAT thesis argues that the sum total of attribution evidence is overwhelming when aggregated together. Moreover, Statutesandstories.com is unable to identify any other Antifederalists who come anywhere close to the alignment between Gerry and the Federal Farmer.

Following the Constitutional Convention, while residing in New York City, Gerry served as a temporary bridge between prominent Antifederalists. In particular, while Congress was meeting in New York, Gerry served as a nexus between Samuel Adams, Richard Henry Lee and other Antifederalists. According to Billias, “Gerry helped Antifederalist leaders keep in contact with one another.”[84] Serving in this role Gerry would have had access to the best arguments being formulated by his Antifederalist colleagues.

Both Gerry and the Federal Farmer used the metaphor that the country was like a patient/man “recovering from” an acute disease/sickness. Gerry wrote to Governor Hancock that “the body politic, after the late ferment, is not unlike a patient recovering from an acute disease, the feeling of both being so exceedingly delicate…any office to me would be extremely painful.”[85] This aligns with Federal Farmer No. 17 who wrote that “[o]ur people are like a man just recovering from a severe fit of sickness. It was the war that disturbed the course of commerce, introduced floods of paper money, the stagnation of credit, and threw many valuable men out of steady business.”

Both Gerry and the Federal Farmer tapped into a wealth of experience, which they wanted to use as a guide. Federal Farmer No. 9 knew “by experience”[86] that only two-thirds of the members of representative bodies regularly attend:

We find by experience, that about two-thirds of the members of representative assemblies usually attend; therefore, of the representation proposed by the convention, about forty-five members probably will attend, doubling their number, about 90 will probably attend: their pay, in one case, at four dollars a day each (which is putting it high enough) will amount to, yearly, 21,600 dollars; in the other case, 43,200 dollars.

This was a Gerry-esque statement, as Gerry had ample experience as a member of the Continental and Confederation Congresses. He was also experienced in state politics in Massachusetts. As described by Georgia delegate William Pierce in 1787, Gerry “had political experience at both the state and national levels,” which gave him “a great degree of confidence.”[87] During his first week at the Convention, Gerry argued that “[i]n Massts. It has been fully confirmed by experience that they [the people] are daily misled into the most baneful measures and opinions by the false reports circulated by designing men, and which no one on the spot can refute.”[88]

As discussed in Part 4, a central focus for both Gerry and the Federal Farmer was securing an adequate “representation of the people.” Gerry argued on July 10 for expanding representation in the House as follows:

Mr. Gerry was for increasing the number beyond 65. The larger the number the less the danger of their being corrupted. The people are accustomed to & fond of a numerous representation, and will consider their rights as better secured by it. The danger of excess in the number may be guarded agst. by fixing a point within which the number shall always be kept.”[89]

The Massachusetts House had 400 members, compared to the Virginia House of Delegates with 150 members and the Rhode Island Assembly of 70. The Massachusetts House met annually and was more democratic than other states.[90]Gerry explained that the people are accustomed to a numerous representation. In fact, representation was the first issue debated at the Massachusetts ratification convention on January 14.

As was common during the ratification debate, both Gerry and the Federal Farmer quoted many of the same authors, Alexander Pope, Montesquieu and Beccaria. While other pamphleteers (including Federalist No. 68), quoted Pope, Federal Farmer No. 1 was the first to do so.[91] The Federal Farmer repeatedly quoted Montesquieu.[92] Gerry’s personal library at the time of his death included copies of Montesquieu, Rousseau and Voltaire.[93] As will be discussed in Part 8 (pending), Melancton Smith quoted Beccaria during the New York ratification convention. Yet, this is not by itself convincing attribution evidence, as the letters of the Federal Farmer were published prior to the New York Ratification Convention.[94]

In March of 1788 Rufus King assumed that “E.G. has come out as a Columbia Patriot.”[95] For many years historians likewise attributed the Columbian Patriot to Gerry. This reflects the fact that it was reasonable to expect that Gerry would write pseudonymously. Having worked closely with Gerry for many years, King knew Gerry well. King was correct that Gerry wrote under a pseudonym, but King was wrong as to which pseudonym.

In 1976 Gerry’s biographer, George A. Billias, noted the similarities between Gerry and the Federal Farmer.[96] While Billias did not stake out the claim that Gerry was the Federal Farmer, Billias did not have access to Kaminski’s attribution[97] when he wrote his Gerry biography:

Lee’s arguments against the Constitution were set forth in the famous essays Letters of the Federal Farmer, which were attributed to him — though their authorship is somewhat doubtful. Many of Lee’s objections were similar to Gerry’s: the Constitution lacked a bill of rights; it provided for a “consolidated” rather than federal government; the lower house was not sufficiently democratic; and the Convention originally called to amend the Articles had exceeded its powers. But Lee, like Mason, was more extreme than Gerry; he kept insisting upon amendments to the Constitution, before, rather than after, its adoption. Lee, in fact, led an unsuccessful move within the Confederation Congress to amend the Constitution before the document was even referred to the states for ratification.

This post continues in Part 7 with a discussion of “Gerry’s endgame,” the adoption of constitutional amendments. Neither Gerry nor the Federal Farmer wanted to rush the adoption of constitutional amendments. Rather, as a member of the First Federal Congress Gerry supported the adoption of essential legislation necessary to establish a working federal government, before proceeding with a robust and transparent amendment process. The content of Gerry’s speeches during the First Federal Congress further illustrates Gerry’s identity as the Federal Farmer.

Endnotes

[1] Expecting strong Antifederalist opposition in New York and Virginia, both states purposefully delayed their ratification conventions until the summer of 1788. Uncertain about the outcome, Antifederalists agreed to delay the Virginia and New York conventions in the hope that opposition would build in other states. Clinton Rossiter, 1787: The Grand Convention (Macmillian, 1966), 293; Michael Klarman, Framers’ Coup: The Making of the United States Constitution (Oxford University Press, 2016),458.

[2] The New York ratification convention was held in Poughkeepsie, away from the Federalist stronghold in New York City. The convention began on June 17 and voted to ratify on July 26, following Virginia’s ratification on June 25th. https://csac.history.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/281/2024/05/DC9_Ratification-at-a-Glance-Table-v2.pdf

[3] The advertisements appeared daily in the Thomas Greenleaf’s New York Journal until July 26 and semiweekly in Samuel and John Loudon’s New York Packet until June 13. DHRC, 20:976.

[4] According to Henry Jackson, a Boston merchant, Gerry’s “infamous” October 18 letter “has done more injury to this Country . . . than he will be able to make atonement in his whole life & by act he has damn’d himself in the Opinion of every liberal judicious & Federal Man in the Community . . . damn him–damn him” – everything look’d well and had the most favorable appearance in this State, previous to this, and now I have my doubt – this measure will either sink him(where he ought to be) or place him at the head of a party of this Commonwealth who are in opposition to all good government – I cannot leave him without once more damn’g him….” Jackson to Henry Knox, 5 November 1787. DHRC, 4:193.

[5] DHRC, 29:1277.

[6] A Plebeian was likely Melancton Smith. DHRC, 19:lxvi; 20:942.

[7] Robert Allen Rutland, The Ordeal of the Constitution: The Antifederalists and the Ratification Struggle of 1787-1788 (1966), 43.

[8] Federal Farmer No. 5.

[9] For example, Madison’s notes on June 12 quote Gerry as follows:

“Mr. Gerry. The people of New England will never give up the point of annual elections, they know of the transition made in England from triennial to Septennial elections, and will consider such an innovation here as the prelude to a like usurpation.” Farrand, 1:214. Additionally, Gerry’s first objection on September 15th at the Convention took issue with the “the duration and re-eligibilty of the Senate.” DHRC, 4:xliii.

[10] For example, some printers initially refused to publish pseudonymous essays unless the author provided their name to the printer, to be disclosed upon request. The Essential Debate, 465.

[11] John P. Kaminski, “The Role of Newspapers in New York’s Debate Over the Federal Constitution,” in Stephen L. Schechter and Richard B. Bernstein, eds., New York and the Union (Albany, 1990), 287.

[12] Congressional Register, June 10.

[13] Kaminski, “The Role of Newspapers,” 285.

[14] Due to the January 30 date, it is reasonable to presume that the pamphlet’s internal advertisement was written several months prior to the newspaper advertisements which began appearing in early May. Massachusetts ratified on February 6 with recommended amendments. This may help explain the differences between the January 30 pamphlet advertisement and the newspaper advertisements.

[15] Farrand, 1:48 (Madison’s notes on May 29).

[16] Farrand 1:132 (Madison’s notes on June 6). See also Gerry to John Wendell dated 16 Nov. 1787: “If the new constitution should be adopted, I shall think it my duty to support it….”

[17] “If those who are in favor of the Constitution, as well as those who are against it, should preserve moderation, their discussions may afford much information and finally direct to an happy issue.” DHRC, 4:99.

[18] Jack N. Rakove, Original Meanings: Politics and Ideas in the Making of the Constitution (New York: Knopf, 1996), 229.

[19] Gordon Wood, “The Authorship of the Lettes from the Federal Farmer,” WMQ, 3rd ser. 31 (1974), 301.

[20] In particular, Rakove pointed to similarities between Smith’s speeches and the letters of the Federal Farmer. Rakove, 228-229.

[21] Kaminski, “The Role of Newspapers,” 287.

[22] Jackson Turner Main, The Antifederalists: Critics of the Constitution, 1781-1788 (Chapel Hill, 1961), 177.

[23] Billias, 154.

[24] DHRC, 37:329.

[25] According to Madison’s notes on May 30:

Genl. Pinkney expressed a doubt whether the act of Congs. recommending the Convention, or the Commissions of the deputies to it, could authorize a discussion of a System founded on different principles from the federal Constitution. Mr. Gerry seemed to entertain the same doubt. Farrand, 1:34.

[26] According to McHenry’s notes of Gerry’s May 30 speech:

A distinction has been made between a federal and national government. We ought not to determine that there is this distinction for if we do it, it is questionable not only whether this convention can propose a government totally different or whether Congress itself would have a right to pass such a resolution as that before the house. The commission from Massachusetts empowers the deputies to proceed agreeably to the recommendation of Congress. This the founding of the convention. If we have a right to pass this resolution we have a right to annihilate the confederation. Farrand, 1:42.

[27] Farrand, 3:260.

[28] Farrand, 1:550.

[29] Farrand, 1:551.

[30] Wood, 301-302.

[31] Kaminski, 286.

[32] Elbridge Gerry to James Warren, 22 March 1789; Billias, 224.

[33] Billias, 224.

[34] DHRC&BR, 37:378.

[35] Farrand, 1:48 (Madison’s notes on May 31).

[36] In subsequent printings, “morrisites” was revised to “m—ites,” referring to the followers of Robert Morris from Pennsylvania. DHRC, 14:54, n. 18.

From 1781 to 1784 Robert Morris served as Superintendent of Finance under the Articles of Confederation. Before accepting the job, Morris drove a hard bargain, insisting on sweeping powers which many New England and Southern delegations opposed. Congress reluctantly agreed to Morris’ conditions believing that only Morris could save the nation from looming insolvency. Richard Beeman, Plain, Honest Men: The Making of the American Constitution (Random House, 2009), 11.

[37] Federal Farmer No. 1.

[38] Farrand, 1:467.

[39] Farrand, 1,233 (June 5).

[40] Farrand, 2:388 (August 23).

[41] Gerry to Wendell 14 September 1789, Fogg Collection, vol. LIV, Maine Hist. Soc.

[42] According to Kaminski, “all” of the Federal Farmer’s positions “appear to be perfectly consistent with Gerry’s stance in the Constitutional Convention.” Kaminski, 287.

[43] Gerry at Convention on 7/14: “He favored the reconsideration with a view not of destroying the equality of votes; but of providing that the States should vote per capita. which he said would prevent the delays & inconveniences that had been experienced in Congs. and would give a national aspect & Spirit to the management of business.” Sherman “had no objection to the members in the 2d b. voting per capita, as had been suggested by (Mr. Gerry)”. Farrand, 2:5.

[44] Federal Farmer No. 11 mentions per capita voting in the Senate, but does not object to senators voting “individually,” as might be expected for an Antifederalist. For example, Luther Martin opposed per capita voting at the Convention on July 23, “as departing from the idea of the States being represented in the 2d. branch.” FF11 suggests several revisions to the operation of the Senate but does not take issue with per capita voting. Rather, FF11 indicates that “the federal senate, in the form proposed, may be useful to many purposes…”

[45] Gerry at the Convention on 9/12: “Mr. Gerry urged the necessity of Juries to guard agst. corrupt Judges. He proposed that the Committee last appointed should be directed to provide a clause for securing the trial by Juries.” Farrand, 2:587.

Gerry at the Convention on 9/15: “Mr. Pinkney & Mr. Gerry moved to annex to the end. “And a trial by jury shall be preserved as usual in civil cases.” Farrand, 2:628.

[46] Federal Farmer No. 3: “…the jury trial of the vicinage is not secured particularly in the large states, a citizen may be tried for a crime committed in the state, and yet tried in some states 500 miles from the place where it was committed; but the jury trial is not secured at all in civil causes.”

FF4: “The trial by jury is very important in another point of view. It is essential in every free country, that common people should have a part and share of influence, in the judicial as well as in the legislative department.”

FF15: “the powers and duties of judges and juries, are too important, as they respect the political system, as was as the administration of justice, not to be fixed on general principles by the constitution”….“directly the opposite principle is established”

[47] Gerry at Convention on 8/18 moved “that in time of peace the army shall not consist of more than thousand men.” “Mr Gerry took notice that there was (no) check here agst. standing armies in time of peace. The existing Congs. is so constructed that it cannot of itself maintain an army. This wd. not be the case under the new system. The people were jealous on this head, and great opposition to the plan would spring from such an omission.” “He proposed that there shall not be kept up in time of peace more than thousand troops. His idea was that the blank should be filled with two or three thousand.” Farrand, 2:329.

Gerry at Convention on 9/5: “Gerry objected that it admitted of appropriations to an army for two years instead of one, for which he could not conceive a reason— that it implied there was to be a standing army which he inveighed against as dangerous to liberty, as unnecessary even for so great an extent of Country as this, and if necessary, some restriction on the number & duration ought to be provided: Nor was this a proper time for such an innovation. The people would not bear it.”

Gerry in Congress, 6/2/1784, “…standing armies in times of peace, are inconsistent with principles of republican Governments, dangerous to the liberties of a free people, and generally converted into destructive engines for establishing despotism.” Journals of the Continental Congress, 27:518.

[48] FF3: “I see so many men in America fond of a standing army, and especially among those who probably will have a large share in administering the federal system.”

FF13: “We all agree, that a large standing army has a strong tendency to depress and inslave the people: it is equally true that a large body of selfish, unfeeling, unprincipled civil officers has a like or a more pernicious tendency to the same point.”

[49] According to his biographer, Gerry was a longstanding opponent of standing armies. “Given Gerry’s republican outlook, one of his greatest fears was that of a standing army within a ‘free state.’ Apprehensive lest the militia created to counter the British be turned against the American people, Gerry insisted upon a highly decentralized military force. He was as anxious to fragment and control military power as much as political power.” Billias, 33.

[50] Gerry to George Washington, 1/13/1778: “this will introduce that Subordination to civil Authority which is necessary to produce an internal Security to Liberty.”

[51] FF6: “The military ought to be subordinate to civil authority”

FF18: “the whole ought ever to be, and understood to be, in strict subordination to the civil authority”

FF18: “military ought ever to be subject to the civil authority, &c.”

[52] Gerry at Convention on 6/13: “Mr. Gerry moved to restrain the Senatorial branch from originating money bills. The other branch was more immediately the representatives of the people, and it was a maxim that the people ought to hold the Purse-strings. If the Senate should be allowed to originate such bills, they wd. repeat the experiment, till chance should furnish a sett of representatives in the other branch who will fall into their snares.” Farrand, 1:233.

Gerry at Convention on 8/13: “Mr. Gerry considered this as a part of the plan that would be much scrutinized. Taxation & representation are strongly associated in the minds of the people, and they will not agree that any but their immediate representatives shall meddle with their purses. In short the acceptance of the plan will inevitably fail, if the Senate be not restrained from originating Money bills.” Farrand, 2:275.

Gerry’s letter to the MA Legislature on 1/22/88 explained the Convention’s reversal on the money bill compromise which Gerry at supported:

“The admission, however, of the smaller States to an equal representation in the Senate, never would have been agreed to by the Committee, or by myself, as a member of it, without the provision ‘that all bills for raising or appropriating money, and for fixing the salaries of the officers of government,’ should originate in the House of Representatives, and ‘not be altered or amended’ by the Senate, ‘and that no money should be drawn from the treasury’ ‘but in pursuance of such appropriations.” “This provision was agreed to by the Convention, at the same time and by the same vote, as that which allows to each State an equal voice in the Senate, and was afterwards referred to the Committee of Detail, and reported by them as part of the Constitution, as will appear by documents in my possession. Nevertheless, the smaller States having attained their object of an equal voice in the Senate, a new provision, now in the Constitution, was substituted, whereby the Senate have a right to propose amendments to revenue bills, and the provision reported by the Committee was effectually destroyed.” “It was likewise conceived, that the right of expending should be in proportion to the ability of raising money — that the larger States would not have the least security for their property if they had not the due command of their own purses.” “…the Commons of Great Britain had ever strenuously and successfully contended for this important right, which the Lords had often, but in vain, endeavored to exercise — that the preservation of this right, the right of holding the purse-strings, was essential to the preservation of liberty — and that to this right, perhaps, was principally owing the liberty that still remains in Great Britain.”

[53] FF9: “In the British government the king is particularly intrusted with the national honor and defence, but the commons solely hold the purse. I think I have amply shewn that the representation in congress will be totally inadequate in matters of taxation…”

FF10: “I have pursued it in a manner new, and I have found it necessary to be somewhat prolix, to illustrate the point I had in view. My idea has ever been, when the democratic branch is weak and small, the body of the people have no defence, and every thing to fear: if they expect to find genuine political friends in kings and nobles, in great and powerful men, they deceive themselves. On the other hand, fix a genuine democratic branch in the government, solely to hold the purse, and with the power of impeachment, and to propose and negative laws, cautiously limit the king and nobles, or the executive and the senate, as the case may be, and the people, I conceive, have but little to fear, and their liberties will be always secure.”

FF17: “purse in the hands of the commons alone”

[54] Gerry at the Convention on 8/22: “Mr. Gerry & Mr. McHenry moved to insert after the 2d. sect. art: 7. the clause following, to wit, “The Legislature shall pass no bill of attainder nor (any) ex post facto law” “Mr. Gerry urged the necessity of this prohibition, which he said was greater in the National than the State Legislature, because the number of members in the former being fewer, they were on that account the more to be feared.” Farrand, 2:375.

[55] FF4: “It is here wisely stipulated, that the federal legislature shall never pass a bill of attainder, or expost facto law; that no tax shall be laid on articles exported, etc. The establishing of one right implies the necessity of establishing another and similar one.”

[56] Gerry at Convention on 8/18: “Mr. Gerry remarked that some provision ought to be made in favor of public Securities, and something inserted concerning letters of marque, which he thought not included in the power of war. He proposed that these subjects should also go to a Committee.” “Mr. Gerry’s motion to provide for (public securities) for stages on post-roads, and for letters of marque and reprisal, were committed nem. con.”

Gerry claimed joint paternity with James Sullivan of the MA Act of Nov 1 1775 to issue letter of marque and establish prize courts (MA Historical Society collection, LXXVII, p 23)

[57] FF18: “I am persuaded, a federal head never was formed, that possessed half the powers….for granting letters of marque and reprisal….”

FF6: mentions that Congress was empowered to “grant letters of marque and reprisal.”

[58] Gerry at Convention on 7/19: “Mr. Gerry. If the Executive is to be elected by the Legislature he certainly ought not to be re-eligible. This would make him absolutely dependent.” Farrand, 2:57.

Gerry at Convention on 7/24: “Mr. Houston moved that he be appointed by the “Natl. Legislature, (instead of “Electors appointed by the State Legislatures”…..“Mr. Gerry opposed it. He thought there was no ground to apprehend the danger urged by Mr. Houston. The election of the Executive Magistrate will be considered as of vast importance and will create great earnestness. The best men, the Governours of the States will not hold it derogatory from their character to be the electors. If the motion should be agreed to, it will be necessary to make the Executive ineligible a 2d. time, in order to render him independent of the Legislature; which was an idea extremely repugnant to his way of thinking.” “Mr. Gerry. That the Executive shd. be independent of the Legislature is a clear point. The longer the duration of his appointment the more will his dependence be diminished — It will be better then for him to continue 10, 15, or even 20 — years and be ineligible afterwards.” Farrand, 2:102.

Gerry at Convention on 7/25: “Gerry supported Pinkney’s motion limiting President to 6 in 12 years.” Farrand, 2:112.

[59] FF14: “A man chosen to this important office for a limited period, and always afterwards rendered, by the constitution, ineligible, will be governed by very different considerations….”

FF14: “any person from period to period may be re-elected president, I think very exceptional.”

FF14: “The convention, it seems, first agreed that the president should be chosen for seven years, and never after to be eligible. Whether seven years is a period too long or not, is rather matter of opinion; but clear it is, that this mode is infinitely preferable to the one finally adopted. When a man shall get the chair, who may be re-elected, from time to time, for life, his greatest object will be to keep it; to gain friends and votes, at any rate.”

[60] Gerry at Convention on 7/20: “Mr. Gerry urged the necessity of impeachments. A good magistrate will not fear them. A bad one ought to be kept in fear of them. He hoped the maxim would never be adopted here that the chief Magistrate could do (no) wrong.”