Eliza’s Visit to Philadelphia – Part 3

Newly compiled evidence is conclusive: Eliza Hamilton traveled to Philadelphia during the Constitutional Convention. Although Eliza’s visit to Philadelphia in June of 1787 has been overlooked by Hamilton biographers, it is now time to tell Eliza’s story. [1] As described below, the emerging details of Eliza’s trip to Philadelphia were a complete mystery – until now. [2]

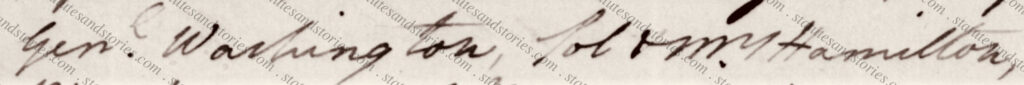

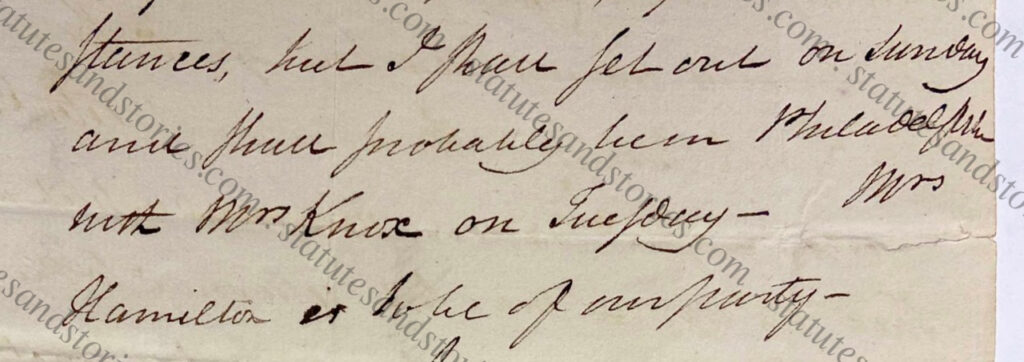

Part 1 introduced the Eliza “Philadelphia Surprise” Thesis, which arose from a recently discovered 8 June 1787 letter from Henry Knox to Rufus King. As described by Knox, he was planning on traveling to Philadelphia with Mrs. Knox and expected to arrive on Tuesday, June 12. This long-overlooked letter is significant because it concludes with the surprising observation that “Mrs. Hamilton is to be of our party.”

Skeptics would be correct to assert that although Knox was planning on traveling to Philadelphia when he wrote to Rufus King, the June 8 letter by itself is not proof that the trip actually took place. Moreover, even if King did depart New York for Philadelphia, the June 8 letter doesn’t prove that “Mrs. Hamilton” was Eliza Hamilton, or that she was able to take the trip as intended.

Part 2 marshalled the abundant evidence that Henry and Lucy Knox did in fact travel to Philadelphia in mid-June, as planned. At the time, the Knox family included four young children. Part 2 thus answered the question of child care. More than half a dozen letters from William Knox, Henry’s brother, provide regular reports regarding the three youngest Knox children. Interestingly, Henry and Lucy’s oldest child (also named Lucy) traveled with the Knoxes to Philadelphia. Thus, Part 2 raises the similar issue of childcare for Eliza Hamilton, who in 1787 also had three young children.

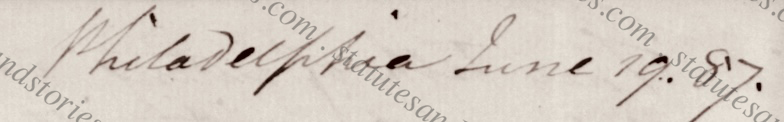

The following post – Part 3 – concludes by presenting definitive evidence of Eliza’s arrival in Philadelphia as late as June 18th. In hindsight, the fact that Eliza was in Philadelphia on 18 June 1787 is not surprising. Monday, June 18, is a date that stands out in the history of the Constitutional Convention. As described by James Madison, “Mr. Hamilton had been hitherto silent on the business before the Convention”. [3] On June 18, Hamilton broke his silence with a day-long speech assailing both the New Jersey and Virginia Plans. Connecticut delegate William Samuel Johnson’s diary on June 18 used a single word to describe the day: “Hamiltn.” [4]

June 18 is the only time that a single delegate controlled the Convention floor for an entire day. Thus, it should be no surprise that Eliza Hamilton was in town for the fireworks. During the Revolutionary War Eliza was not afraid to visit Valley Forge. She also regularly traveled from New York City to her parents’ estate in Albany.

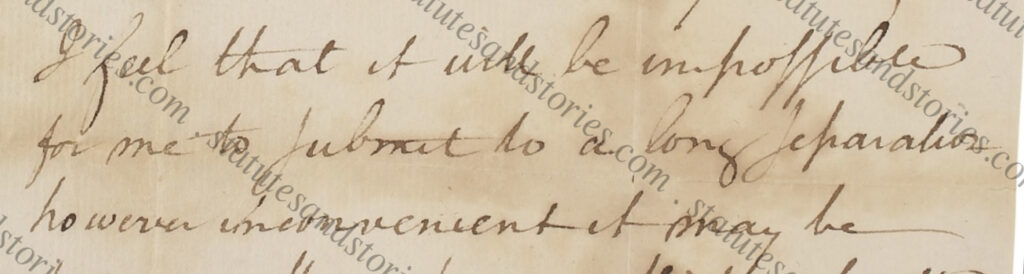

Part 3 builds on an undated letter from Alexander to Eliza (the “love letter”) written between 1786 and 1788. In the love letter Hamilton regretted that he could not yet determine the length of his stay, “but I feel that it will be impossible for me to submit to a long separation…” Accordingly, Part 3 argues that the undated love letter was necessarily written in May of 1787. Connecting the dots, the “May 1787” love letter was Alexander’s invitation to Eliza to take a trip to Philadelphia.

Pictured below is an excerpt from a 19 June 1787 letter from Dr. William Shippen, describing a tea party hosted by his daughter that took place on June 18. Shippen’s letter is unmistakable. Three of the attendees at the Shippen tea party were General Washington and “Colonel & Mrs. Hamilton.”

As set forth below, Shippen’s June 19 letter contains a description of Hamilton’s June 18 speech. It also places Eliza in Philadelphia no later than June 18. It is also significant that both Hamiltons were listed immediately following General Washington, in a list of invited guests at the Shippen party.

Overview of the evidence of Eliza’s Philadelphia trip

Taken together, the following evidence overwhelmingly establishes that Eliza Hamilton was in Philadelphia during the Constitutional Convention in June of 1787:

- The recently uncovered Henry Knox’s June 8 letter to Rufus King indicating that Mrs. Hamilton would be in our party traveling to Philadelphia (discussed in Part 1)

- Hamilton’s undated love letter written between 1786 and 1788 bemoaning that it would be “impossible for me to submit to a long separation…” given the indeterminate length of their separation (discussed in Part 1)

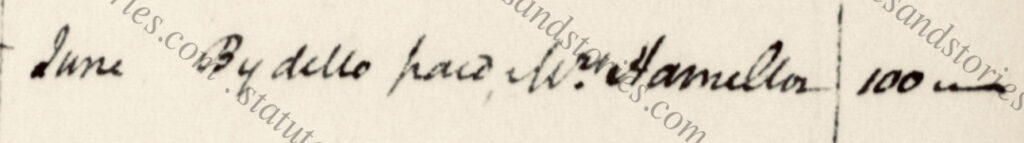

- Hamilton’s cash book entry in June (of 1786 or 1787) reflecting payment of £100 to Eliza from her brother-in-law, Stephen Van Rensselaer (discussed in Part 1)

- Multiple letters from William Knox to Henry Knox in June of 1787 confirming that Henry and Lucy in fact traveled to Philadelphia (discussed in Part 2)

- The June 19 letter from Dr. Shippen to his son in London describing Shippen’s tea party guests and conversations

Shippen’s June 19 letter

Born into a prominent Philadelphia family, Dr. Wiliam Shippen graduated from the College of New Jersey (now Princeton) in 1754. After studying medicine in Europe, he became one of the first medical professors at the newly founded medical school at the College of Philadelphia. In 1762 he married Alice Lee, the daughter of Thomas Lee from the famous Virginia Lee dynasty. During the Revolutionary War Shippen served as director general of hospitals and helped reorganize the army medical department. [5] His daughter, Anne Shippen, became a famous diarist following her unsuccessful marriage to Henry Beekman Livingston. [6]

Given his stature in Philadelphia, Shippen personally knew many of the Convention delegates, including military leaders that he served with during the War. Shippen regularly corresponded with his son who was studying in Europe. The Shippen manuscripts are held by the Library of Congress and provide an insider account of Philadelphia society in 1787, including a discussion of interactions with Convention delegates.

Beginning in May of 1787, Dr. Shippen memorialized the arrival of Convention delegates in Philadelphia. As his wife, Alice, was a Lee from Virginia, it is clear that the Shippens were friendly with the Virginia delegates, who are mentioned in the Shippen manuscripts. For example, on May 13 Shippen describes a visit with “your friends Wythe & Blair.” Shippen was also friendly with Henry Knox, whose name begins appearing as early as May 12. Knox was in town in May for a meeting of the Society of Cincinnati. [7] Knox would subsequently return to Philadelphia in mid-June, as described in Part 2.

Dr. Shippen’s June 19 letter to his son, Thomas Lee Shippen, is remarkable. Notwithstanding the “rule of secrecy” adopted by the Convention, it is clear that Shippen was actively following the Convention’s proceedings. He reports that the Convention was “very busy and very secret.” While it is unlikely that he was privy to specific deliberations, Shippen’s letter quotes Convention Secretary William Jackson that “Colonel Hamilton spoke 3 hours yesterday and Jackson says well.”

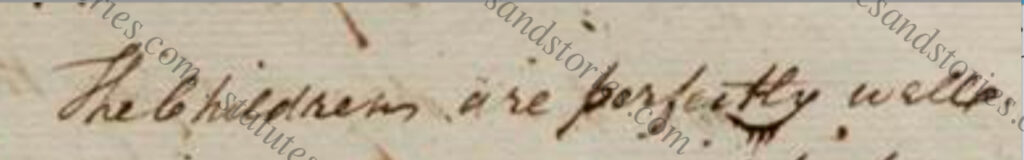

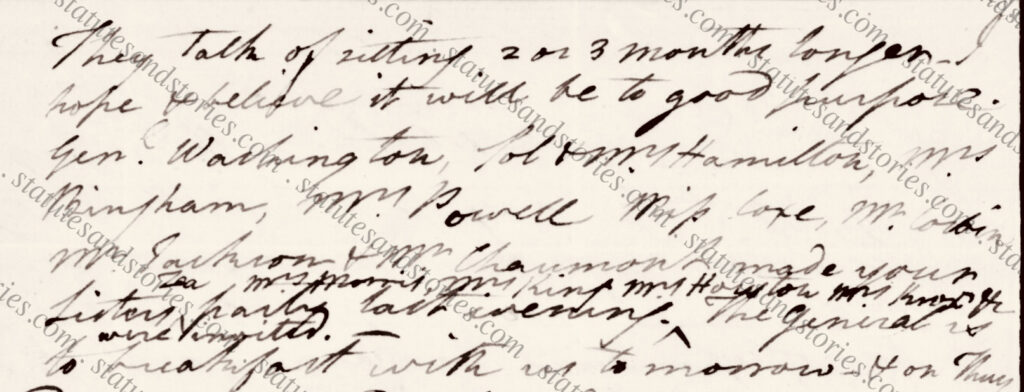

After mentioning Hamilton’s speech, Shippen also complements the Convention delegates as a “learned and good” group. On the second page of the June 19 letter Shippen indicates that “[t]hey talk of sitting 2 or 3 months longer. I hope and believe it will be to good purpose.”

Immediately thereafter Shippen mentions that “General Washington, Colonel and Mrs. Hamilton, Mrs. Bingham, Mrs. Powell, Mrs. Coxe….made your sister’s party last evening.” Given the context, there can be no doubt that the “Mrs. Hamilton” mentioned above by Dr. Shippen is none other than Eliza Hamilton.

Unlike Knox’s long-overlooked June 8 letter to Rugus King, Shippen’s June 19 letter was hiding in plain sight at the Library of Congress. Although no Hamilton biographers have discussed Eliza’s trip to the Convention in June, historians from Independence National Historic Park (INHP) concluded in the 1980s that Eliza was one of as many as nine wives who likely “attended” the Convention. [8] Part 4 (pending) will discuss Eliza Hamilton’s relationship with the other eight wives who likely were in Philadelphia during the Convention, including Rufus King’s wife, Mary Alsop King, who was a native New Yorker.

Connecting the dots

Piecing together clues from the sources discussed above, it is possible to deduce the following:

- Date of Eliza’s arrival: Based on Henry Knox’s June 8 letter to Rufus King, it is likely that Eliza arrived in Philadelphia mid-month, around June 12. The daily stage coaches from New York to Philadelphia involved a grueling three-day trip. Henry Knox informed King that the Knoxes planned to depart on Sunday (June 9) and arrive in Philadelphia on Tuesday (June 12). This three-day itinerary is consistent with a three-day stagecoach trip.

- Philadelphia surprise: Henry Knox’s June 8 letter to Rufus King was not the first indication that the “Secretary at War” would be returning to Philadelphia. By letter dated May 29th, Knox also alerted George Washington that “I hope to be able so to arrange my business as to accompany Mrs. Knox to Trenton in the course of next week, and thence to Philadelphia for a few days, at which some public business requires me to be present.” Knox similarly shared his intent to return to Philadelphia with Rufus King. By letter dated June 3, Rufus King confirmed that “Mrs. King & myself shall expect you and Mrs. Knox in about six or eight says.” Interestingly, neither Knox’s May 29 letter to Washington nor King’s June 3 letter to Knox provided any hint that Eliza would be traveling with the Knoxes. It is for this reason that the Eliza Hamilton Surprise Thesis theorizes that Eliza’s decision to travel to Philadephia was a last-minute decision and/or a surprise (to historians and potentially to Alexander Hamilton himself).

- Date of Eliza’s return: Apart from Dr. Shippen’s June 19 letter, Eliza’s name does not reappear in the Shippen manuscripts in 1787. This potentially suggests that her Philadephia trip was relatively brief. While it is likely Eliza attended other parties in Philadelphia with Alexander, Dr. Shippen doesn’t necessarily mention the names of all party attendees. Moreover, it is unlikely that Dr. Shippen was invited to all social functions attended by the delegates. Accordingly, Shippen’s manuscripts do not answer the question of when Eliza returned to Philadelphia.

- Other social functions with George Washington: Shippen’s June 19 letter mentions that “the General is to breakfast with us tomorrow.” It is unclear who else attended breakfast on June 20th with Washington and the Shippens. George Washington’s diary does not mention breakfast at the Shippens on June 20. Nevertheless, his diary entry on June 16 indicates that Washington dined at the Club at City Tavern and “drank tea at Doctr. Shippins with Mrs. Livingston’s party.” [9] Washington’s diary on June 18 likewise records that he “drank tea at Doctr. Shippins with Mrs. Livingston,” which corroborates Dr. Shippen’s June 19 letter.

- Omissions in George Washington’s diary: It is noteworthy that Washington made no effort to record the names of the attendees at the tea party at the Shippens on June 18, including Alexander and Eliza. This may be because Washington was merely keeping track of the hosts on his social calendar. Thus, Washington’s diary should not be considered a typical diary in the common understanding of the term today. [10] According to his diary on June 19, Washington “dined in a family way at Mrs. Morris’s and spent the evening there in a very large company.” One can reasonably anticipate that the Knox family and Hamilton family likely were in this “very large company.”

- Alexander Hamilton’s Convention attendance: Alexander Hamilton spoke at the Convention on June 29. The Convention did not hold sessions on Sunday, June 30, so it is conceivable that he departed with Eliza as early as June 30. Hamilton is not mentioned in Madison’s notes as participating at the Convention in July. Hamilton reemerges briefly on August 13. He returned a third time on September 6 and remained at the Convention until it concluded on September 17. [11]

- Alexander Hamilton at the New York Society of Cincinnati meeting on July 5: It is reasonable to assume that Eliza returned to New York with Alexander on or after June 30. Records of the New York chapter of the Society of the Cincinnati confirm that Hamilton was back in New York to attend a meeting on July 5th.

Eliza’s eventful summer

The Constitutional Convention was a seminal event in American history. The summer of 1787 was also a busy time for Eliza Hamilton. Alexander left home in mid-May for the Convention. In mid-June, as described above, Eliza traveled to Philadelphia to visit Alexander. After the Hamiltons returned to New York in early July, the Hamiltons agreed to expand their household with “an exceptional act of kindness that has been long overlooked…” [12] They brought an orphan, Fanny Antill, into their home and raised her as their own.

Fanny’s father, Colonel Edward Antill, became a widower in 1785 with six children. By 1787 he was penniless, depressed and suffered a breakdown. As described by John Church Hamilton, when Colonel Antill visited New York to solicit the aid of the Cincinnati, Hamilton “immediately took the little orphan home….” [13] Eliza’s sister, Angelica, was even more effusive in her praise for the Hamiltons. From London, Angelica wrote that, “All the graces you have been pleased to adorn me with, fade before the generous and benevolent action of My Sister in taking the orphan Antle under her protection.” Although the exact date when the Hamiltons brought Fanny home is unknown, Angelica’s letter was written on 2 October 1787. As it took approximately six weeks for a ship to sail from New York to London, the Hamiltons likely brought Fanny home in early July, following a Society of Cincinnati meeting on July 5th.

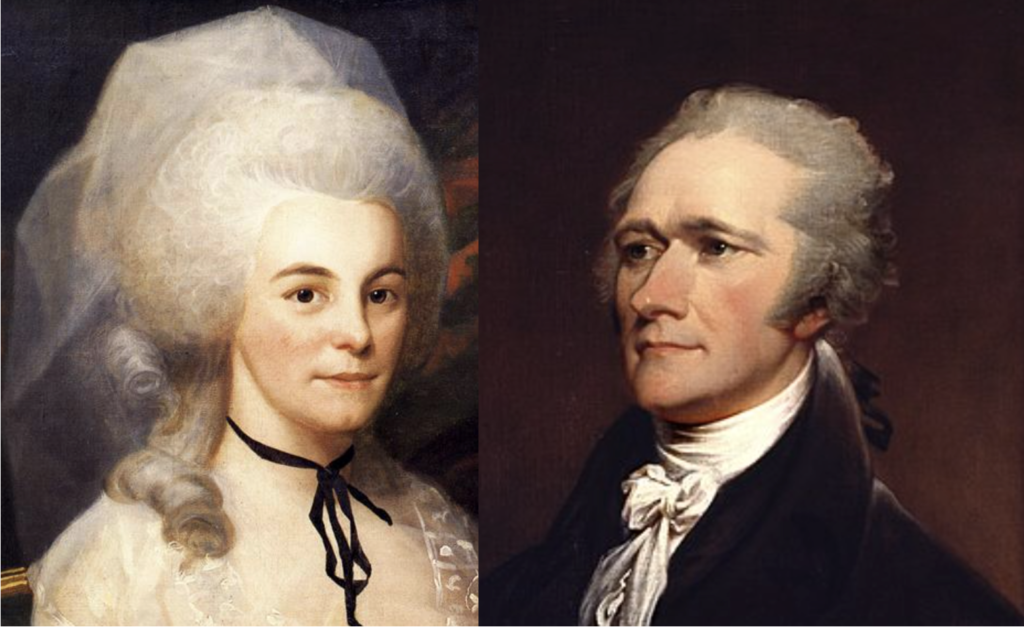

Another act of generosity by the Hamiltons was memorialized in Eliza’s portrait pictured above. James A. Hamilton, one of the Hamilton children, recounts the story of how his parents helped painter Ralph Earl. When Earl was thrown into debtors prison, Eliza agreed to sit for a portrait in jail to raise money to pay Earl’s debts. Eliza also “induced other ladies to do the same.” [14] While the exact date of the portrait is unknown, the portrait was painted in 1787.

Other details of Eliza’s trip remain unclear. When did Eliza arrive in Philadelphia? What did she do in Philadelphia? Did Alexander collaborate with Eliza in preparation for his June 18 speech? These and other questions will be addressed in Part 4 (pending).

Footnotes

[1] Following Alexander Hamilton’s tragic death in 1804, Eliza made it her life mission for the next fifty years that “Justice shall be done to the memory of my Hamilton.” Ron Chernow, Alexander Hamilton, 3 (2004), citing Elizabeth Hamilton Holly to John C. Hamilton, 27 February 1855.

[2] Statutesandstories is grateful for the assistance and friendship of Eunho Jung, who helped scour through archives at Independence National Historical Park.

[3] According to Madison’s notes for June 18:

Mr. HAMILTON, had been hitherto silent on the business before the Convention, partly from respect to others whose superior abilities age & experience rendered him unwilling to bring forward ideas dissimilar to theirs, and partly from his delicate situation with respect to his own State, to whose sentiments as expressed by his Colleagues, he could by no means accede. The crisis however which now marked our affairs, was too serious to permit any scruples whatever to prevail over the duty imposed on every man to contribute his efforts for the public safety & happiness. He was obliged therefore to declare himself unfriendly to both plans. He was particularly opposed to that from N. Jersey, being fully convinced, that no amendment of the Confederation leaving the States in possession of their Sovereignty could possibly answer the purpose.

Farrand, 1:282

[4] Farrand, 3:552. William Samuel Johnson would subsequently observe that although Hamilton’s speech “has been praised by everybody, he has been supported by none.” Farrand, 1:363. Historian Richard Beeman describes Hamilton’s June 18 speech as “an extraordinary exegesis of his political philosophy.” Richard Beeman, Plain, Honest Men (2009), 164. The following day, the Convention voted to reject the New Jersey Plan. The Convention would subsequently combine together elements of the Virginia and New Jersey plans on July 16, when the Connecticut Compromise was adopted.

[5] https://archives.upenn.edu/exhibits/penn-people/biography/william-shippen-jr/

[6] Add citations….. (Discuss Livingston clan, unsuccessful marriage). Regrettably. Anne wasn’t making diary entries during the Constitutional Convention.

[7] According to a letter dated May 7 (recording several days of activities), General Knox visited the Shippen house for 4 hours on May 12. The amusements that day with Knox and Colonel Humphreys included “chess, music, and political commerce.”

[8]. In preparation for the Constitution’s bicentennial in 1787 INHP historians prepared the Daybook of 1787, which contains a day-by-day account of the archival research for the year 1787. While the Daybook quotes from Shippen’s June 19 letter, the Daybook researchers did not identify how or when Eliza traveled to Philadelphia, which is discussed in Part 1 and 2. Portions of Shippen’s June 19 letter were transcribed by James Hutson in 1987, but Hutson omitted any discussion of the Shippen tea party attended by General Washington and the Hamiltons on June 18.

[9] It is clear that when Washington referred to “Mrs. Livington’s party” he was referring to Anne Shippen, Dr. Shippen’s daughter. The editors of The Diaries of George Washington, Donald Jackson and Dorothy Twohig indicate that: Anne Hume Shippen (1761–1841) was the daughter of Dr. William Shippen (1736–1808). She married (1781) Henry Beekman Livingston, son of Judge Robert R. Livingston (1718–1775), but at this time the Livingstons were separated. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/01-05-02-0002-0006

[10] According to the editors of Washington’s Diaries:

The diaries of George Washington are not those of a literary diarist in the conventional sense. No one holding the long-prevailing view of Washington as pragmatic and lusterless, a self-made farmer and soldier-statesman, would expect him to commit to paper the kind of personal testament that we associate with notable diarists…

But let us not be unfair to a man who had his own definition of a diary: “Where & How my Time is Spent.” The phrase runs the whole record through. He accounts for his time because, like his lands, his time is a usable resource. It can be tallied and its usefulness appraised. Perhaps it was more than mere convenience that caused Washington to set down his earliest diary entries in interleaved copies of an almanac, for an almanac, too, is an accounting of time.

[11] Farand, III:588.

[12] Chernow, 203.

[13] John Church Hamilton, Life of Alexander Hamilton: A History of the Republic of the United States of America, as Traced in His Writings and Those of His Contemporaries (1879), III:362.

[14] James A. Hamilton, Reminiscences of James A. Hamilton (1869), 4.