Jay’s Treaty (Part II) – The Bitter Ratification Battle, Hyperpartisianship and Executive Privilege

Overview: A prior post, Jay’s Treaty (Part I), described the background behind the treaty, its terms, and its geopolitical importance. The Camillus essays, Jay’s Treaty (Part III), explores Alexander Hamilton’s heroic essays defending the treaty. This post continues the discussion of Jay’s Treaty by exploring the close ratification debate in the Senate and the divisive funding battle in the House of Representatives. The vocal opposition to Jay’s Treaty was a watershed moment in American history that exacerbated deepening political divisions between the Federalist proponents of the treaty and the Democratic Republican opposition, led by the future presidents Jefferson and Madison.

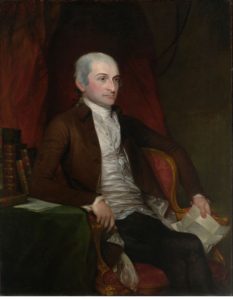

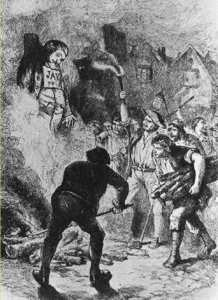

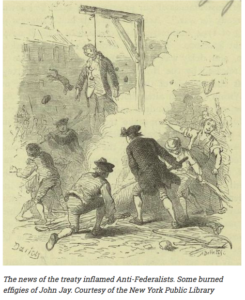

John Jay is pictured above in a portrait by John Trumbull in the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery. The scene below depicts Jay being burned in effigy. Jay joked that he could have walked the length of America by the glow of his burning likeness. In Boston, graffiti famously declared, “Damn John Jay! Damn everyone who won’t damn John Jay!! Damn everyone that won’t put lights in his windows and sit up all night damning John Jay!!!”

The controversy surrounding Jay’s Treaty in the mid-1790’s provides meaningful context for today’s partisan disputes over NAFTA, the Paris Climate Agreement, and President Obama’s Iran nuclear deal. In other words, the early days of the United States were noteworthy for hyper-partisan clashes over foreign policy, that easily could have resulted in war.

“No international treaty was ever more passionately denounced in the United States, though the benefits which flowed from it were considerable.” The Age of Federalism: The Early American Republic, 1788-1800 (Stanley Elkins & Eric McKitrick, 1993). Likewise, according to historian Jerald Combs, “The treaty that Jay negotiated with England in 1794 was one of the most crucial in United States history. It was also one of the most bitterly debated.” The Jay Treaty: Political Background of the Founding Fathers (Jerald A. Combs, 1970).

Historian Joseph Ellis describes the controversy over Tay’s Treaty as the greatest crisis of the Washington presidency. His Excellency: George Washington at 226 (Ellis, 2005). For Ellis, Jay’s Treaty represented Washington’s “most besieged,” but “finest hour”:

No treaty in American history generated so many diplomatic, constitutional, and political reverberations; and no treaty so unpopular in its own day proved so beneficial over the stretch of time.

Ratification and funding battle leading to crystallization of political parties: The presidential leadership shown by Washington in the face of substantial opposition to Jay’s Treaty set the precedent that a President should attempt to lead public opinion, not merely defer to it. Washington recognized that his prestige was a unique resource. He employed the full weight of his office to convince Congress and the American people of the wisdom of an unpopular treaty that was in the national interest, at great harm to his cherished reputation. Importantly, Washington and his Federalists allies (led by Alexander Hamilton, Rufus King, and Fisher Ames) succeeded in implementing the Jay Treaty. Nevertheless, Madison, Jefferson and their allies used the unpopularity of the treaty to solidify support for the expanding Democratic Republican party. Historian Joseph Ellis suggests that the Democratic Republicans were looking for a winning issue after the Whiskey Rebellion and the unpopular Jay Treaty provided the perfect vehicle to oppose the Federalists.

Jay’s Treaty ultimately became a lightening rod that transformed the Federalists and Democratic Republicans from temporary factions into full blown political parties. The partisan battle over funding Jay’s Treaty also gave rise to the first significant rift in American history between the President and Congress.

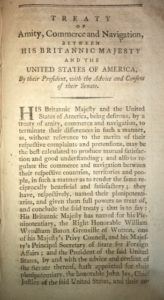

After secret deliberations in June of 1795, the Senate passed a resolution advising Washington to amend the treaty by suspending the controversial 12th article of the treaty (which severely restricted American rights to trade with the British West Indies). On August 14, 1795, the Senate ratified the treaty 20–10 (the narrowest margin of victory). The final Senate vote was based upon the condition that Article 12 be suspended, pursuant to the June 24 resolution. President Washington signed the treaty on August 18, 1795. The Treaty took effect on February 29, 1796 and the reluctant House funded it in April of 1796.

After Jay’s Treaty was narrowly approved by the Senate, Madison attempted to undermine it in the House and irreparably harmed his formerly close relationship with Washington in the process.

Madison supported a congressional resolution formally requesting that Washington release records of the negotiations, including the private instructions to Jay (which had in fact been drafted by Alexander Hamilton). In refusing to comply, Washington laid the precedent for the doctrine of executive privilege. In the tug of war between the President and the House, Washington successfully resisted encroachment on the President’s executive authority to lead foreign policy.

Madison also asserted that the treaty regulated commerce and thus required House approval. When the House finally voted on funding Jay’s Treaty after weeks of debate, the result was a 49 to 49 tie. Republican Frederick Muhlenberg, who was Chairing the Committee of the Whole, was the tie breaking vote. He shocked everyone by supporting the treaty, committing an act of political suicide in the process.

In an overlooked advisory opinion, Chief Justice Oliver Ellsworth also rejected the House’s authority to interfere with a treaty that had been ratified. Ellsworth opined that the treaty-making power is vested exclusively in the President and the Senate. Ellsworth reasoned that once a treaty has been ratified and signed by the President, it becomes the “law of the land” and is binding upon the House. The fact that the Treaty required an appropriation was “an accidental circumstance [that did] not give the house any more right to examine the expediency of the Treaty, or control its operation, than they would have without this circumstance.” The House was therefore duty bound, Ellsworth concluded, to appropriate the necessary funds “as it is to appropriate for the President’s salary, or that of the Judges.”

The following examples illustrate the bitter dispute over Jay’s Treaty which was one of the reasons that Washington declined to run for re-election to a third term in 1796:

- The passionate controversy over Jay’s Treaty began as soon as Jay was nominated. Senators opposed to Jay’s appointment asserted that the Supreme Court Chief Justice should not simultaneously hold a diplomatic post. Other senators argued that while Jay was experienced in foreign affairs, he was too sympathetic to the British.

- The Democratic-Republican newspaper, the Auroa, sarcastically suggested that Jay had been selected by Washington because he could not be impeached if the Chief Justice was out of the country.

- It was not by accident that Jay later resigned as Chief Justice in 1795 to become Governor of New York. Some historians have suggested that he did so to avoid possible impeachment by the House. John Adams noted that he was happy “that Mr. Jay’s election was over before the treaty was published; for the parties against him would have quarrelled with the treaty, right or wrong, that they might give color to their animosity against him.”

- The bitter struggle over Jay’s Treaty ultimately ended the formerly close personal relationship between President Washington and James Madison. Washington never again sought Madison’s advice, never re-invited him to Mount Vernon, and never forgave him for his disloyalty.

- A copy of the treaty was leaked to the press during the Senate debate, despite President Washington’s specific instructions to keep the terms “rigidly” secret “from every person on earth.” The publication of the treaty in the Aurora was described by David McCullough in his autobiography of John Adams as the “first scoop in American newspaper history,” after which a “battle royal commenced at once.”

- Secretary of State Edmund Randolph resigned in 1795 due to rumors that he was secretly working with the French to undermine the treaty. It is also possible that Randolph had been bribed by the French, which he denied when confronted by Washington.

- After his resignation Randolph published a 103-page pamphlet, entitled Vindication, claiming that Washington was growing senile.

- In Boston Harbor mobs protested the treaty by setting ablaze a British ship.

- Alexander Hamilton was pelted with stones in front of City Hall in New York when he tried to speak in favor of the treaty.

- As described by John Adams, Washington’s house in Philadelphia was “surrounded by an innumerable multitude, from day to day buzzing, demanding war against England, cursing Washington, and crying success to the French patriots and virtuous Republicans.” Years later, in a letter dated 10/15/1808, Adams described the “near universal” enthusiasm for France and the French Revolution “throughout the United States” at the time.

- Philadelphia mobs chanted, “Kick this damned treaty to hell!” Stone throwing protesters marched to the Philadelphia home of Senator William Bingham. After spearing a copy of Jay’s Treaty with a pole, the protestors marched to British ambassador George Hammond’s house. With the ambassador and his family home, the crowd broke windows and burned the treaty at the front door.

- The Kentucky Legislature was furious with Federalist Senator Humphrey Marshall for voting to ratify the treaty and called for amending the state constitution to allow the recall of senators.

- Chief Justice John Rutledge of South Carolina had been selected by Washington as a recess appointment to replace John Jay on the Supreme Court. Based on Rutledge’s outspoken criticism of the treaty, his appointment was rejected by the Federalists when the Senate reconvened in December 1795.

- Speaker of the House Frederick Muhlenberg was stabbed by his brother-in- law after he cast the tie-breaking vote in favor of funding the treaty in the House.

- The Democratic Republicans in the House stopped recognizing President Washington’s birthday due to the personal animosity with the Washington Administration.

- Thomas Paine called Washington a “hypocrite in public life” and questioned whether Washington was an apostate or imposter.

- The bitter climate led to toasts for a “speedy death to General Washington!” and political cartoons showing Washington being marched to a guillotine.

- Washington wrote to Jay in May of 1796 that he had ridden out “the Storm,” but could never forget the “Inventors” of “pernicious” measures disseminating “poison” against him. The experience had “worn away my mind,” making “retirement indispensably necessary.” Washington also confided to Jay that unless some crisis made it “dishonorable,” he would not seek reelection.

- After funding was narrowly approved by the House, James Madison did not take defeat well. He contemplated retiring from Congress and returning to Virginia. “His earlier friendship with the President was over. Washington never forgave him for his attempts to undermine the treaty and never consulted him again,” according to historian Gordon Wood.

- Washington was inundated with petitions from across the country demanding that he refuse to sign the treaty. Washington expressed concern over the possibility “of a separation of the Union into Northern & Southern” after reading resolutions threatening secession.

- During the Senate debate Democratic Republican Aaron Burr tried to pit Southern Senators against Jay’s Treaty by demanding that Britain pay for slaves and other property stolen from the South during the Revolutionary War. Ultimately this issue helped galvanize support for the party in the Southern states.

- John Adams wrote to his wife Abigail on April 19, 1796 that it is “difficult to see how we can avoid war” with Britain if the House denied funding for the treaty.

- Adams also worried that a war with England might lead to an American “civil war” between the Anglophile Northeast and Southern Francophiles.

- Democratic Republican professed loyalty to France and supported the spread of democracy in Europe. The Democratic Republicans viewed the French Revolution as the continuation of the republican struggle against tyranny. An irony, of course, was that the Jeffersonian support for democracy did not extend to the enslaved population in the American South.

Executive privilege: In August of 1795, Jay’s Treaty squeaked through ratification in the Senate with the bare minimum votes necessary for a 2/3 majority (20 – 10). Democratic Republicans realized that the only other opportunity to resist the treaty was to refuse to appropriate funding.

When the House began consideration of the funding bill in March of 1796, the Democratic Republicans requested that Washington submit “a copy of the instructions to the minister of the United States who negotiated the treaty with the king of Great-Britain, (communicated by his message of the first instant) together with the correspondence and other documents relative to the said treaty.”

President Washington refused, in so doing establishing the doctrine of executive privilege. Under this doctrine, the president retains the implied power to withhold information from Congress. The House suggested that Washington’s correspondence with John Jay would shed light on the constitutionality of the treaty. Washington replied that the Constitutional “explicitly rejected” a role for the House in the adoption of treaties.

In a letter dated March 25, 1796 Washington requested the opinion of his cabinet on this question. After deliberating with his cabinet, Washington replied to the House in a letter dated March 30, 1796. Washington explained:

The nature of foreign negociations requires caution; and their success must often depend on secrecy: and even when brought to a conclusion, a full disclosure of all the measures, demands, or eventual concessions, which may have been proposed or contemplated, would be deemed impolitic; for this might have a pernicious influence on future negociations, or produce immediate inconveniences, perhaps danger and mischief, in relation to the other powers. The necessity of such caution and secrecy was one cogent reason for vesting the power of making treaties, in the President, with the advice and consent of the Senate; the principle, on which that body was formed, confining it to a small number of members. To admit, then, a right in the House of Representatives, to demand, and to have, as a matter of course, all the papers respecting a negociation with a foreign power, would be, to establish a dangerous precedent.

As the very “nature of foreign relations requires caution,” Washington observed that disclosure of diplomatic correspondence “would be to establish a dangerous precedent.” Washington correctly understood that in treaty making was explicitly reserved to the Senate, which was a smaller and more deliberative body.

Washington assured the House that he had forwarded to the Senate “all the Papers affecting the negotiation with Britain.” He further explained that he had “no disposition to withhold any information, which the duty of my station will permit, or the public good will require to be disclosed.”

Washington understood that the House request was based on partisan motivations. He later confided to Alexander Hamilton that regardless of which correspondence he might send to the House, the treaty’s opponents would not be satisfied.

Washington elaborated that the Constitution vested “the power of making treaties in the President, with the advice and consent of the Senate, the principle on which that body was formed confining it to a small number of members.” Washington was not shy in defending his position that the House had limited authority in this area:

It does not occur to me that the inspection of the papers asked for can be relative to any purpose under the cognizance of the House of Representatives, except that of an impeachment, which the resolution has not expressed.

Fisher Ames floor speech in the House: Despite his failing health, Fisher Ames of Massachusetts rose to the occasion to deliver a passionate floor speech favoring Jay’s Treaty. John Adams described Ames’ oration in a letter to Abigail dated April 30, 1796:

….in his feeble State, Scarcely able to stand upon his Legs and with much difficulty finding Breath to utter his Periods, made one of the best Speeches he ever produced to the most crouded Audience ever assembled. He was attended to with a silence and Interest never before known and he made an Impression that terrified the hardiest and will never be forgotten.

Adams’ contempt for certain Democratic Republican colleagues is also evident in the letter:

Tears enough were shed—not a dry Eye I believe in the House, except Some of the Scoundrels Jack Asses who had occasioned the Necessity of the oratory— These attempted to laugh—but their Vissages grinn’d horrible ghastly smiles.

Fisher Ames warned against the House of Representatives breaking a lawfully ratified treaty under the Constitution. He feared that despite his poor health, he might outlive the nation if the House sabotaged the treaty. Ames’ speech is recorded in the The Debates and Proceedings of the Congress by Gales and Seaton, House, Fourth Congress, 1st Session (otherwise known as the Annals of Congress) at pages 1239 – 1263.

Washington’s thinking and his letter to the Selectmen of Boston: The following letter to the Selectmen of Boston dated July 28, 1795, illustrates the President’s thinking in approaching his executive duties:

Gentlemen: In every act of my administration, I have sought the happiness of my fellow-citizens. My system for the attainment of this object has uniformly been to overlook all personal, local and partial considerations: to contemplate the United States, as one great whole: to confide, that sudden impressions, when erroneous, would yield to candid reflection: and to consult only the substantial and permanent interests of our country….While I feel the most lively gratitude for the many instances of approbation from my country; I can no otherwise deserve it than by obeying the dictates of my conscience.

Final Outcome: The Federalists narrowly prevailed after Washington threw his full prestige behind the treaty. Alexander Hamilton wrote thirty-eight essays under the pseudonym Camillus to help rally public opinion. Hamilton’s Camillus essays were almost comparable in scope to his work on the Federalist Papers. The protracted debate in Senate in 1795 which continued into the House in 1796 allowed time for public tempers to cool. Merchants and laborers alike began to appreciate the value of expanding trade with Britain. One of Washington’s final legacies was thus his insistence that the United States needed to remain neutral and avoid becoming entangled in unnecessary European wars.

Years later, when Thomas Jefferson became president in 1801, he declined to repudiate Jay’s Treaty. Instead, Jefferson allowed Jay’s Treaty to expire in 1805 at the conclusion of its ten year term. Although he rejected renewal of the Jay Treaty, Jefferson allowed Federalist ambassador Rufus King to remain in London (to negotiate a successful resolution to outstanding issues of cash payments and boundaries). Anglo – British relations turned increasingly hostile thereafter, eventually resulting in the War of 1812. Nevertheless, Jay’s Treaty purchased twenty years of prosperity which enabled the United States to fight another day, on its own terms.

Debates in the House (Annals of Congress)

John Jay’s papers (Columbia University)

Uproar Over Senate Approval of Jay’s Treaty (U.S. Senate)

Jay’s Treaty (Lerman Institute)

The First Rapprochement: England and the United States, 1795 – 1805, Bradford Perkins (1955)

The Federalist Era, 1789-1801, John C. Miller (1963)

The Age of Federalism: The Early American Republic, 1788-1800 Stanley Elkins and Eric McKitrick (1993)

Thomas Jefferson: The Art of Power, Jon Meacham (2013)

Washington: The Indispensable Man, James Thomas Flexner (1969)

Founding Brothers: The Revolutionary Generation, Joseph Ellis (2000)

The Jay Treaty: Political Battleground of the Founding Fathers, Jerald A. Combs (1970)