Hamilton’s defense of Jay’s Treaty (the Camillus essays):

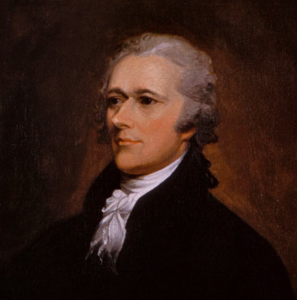

This post continues the discussion of Jay’s Treaty by focusing on Hamilton’s Camillus essays which were published between July of 1795 and January of 1796. The negotiation and substance of the treaty is discussed in the blog entry Jay’s Treaty – Part I. The bitter ratification dispute in the Senate and the highly politicized funding dispute in the House of Representatives is described in Jay’s Treaty – Part II. As set forth below, the Camillus essays are easily overlooked but are in many ways comparable in scope to Hamilton’s monumental scholarship in the much better known Federalist Papers.

Overview: Twenty-eight essays were published anonymously as newspaper columns by Hamilton using the pseudonym Camillus. Hamilton edited another ten Camillus essays which were written by Federalist Senator Rufus King. Four more related essays were written by Hamilton under the moniker Philo Camillus, bringing the total to forty-two essays. Noah Webster authored a dozen articles defending Jay’s Treaty under the pseudonym Curtius. Another eloquent and thoughtful defense was offered under the pseudonym Macellus, who was likely John Quincy Adams.

In the face of furious opposition to Jay’s Treaty, Hamilton wrote the Camillus essays in an effort to sway public opinion, save the treaty, and avoid war with England. The essays were written at the frenetic pace that Hamilton was known for, averaging a new essay every four and a half days over a five month period. Altogether, Hamilton churned out almost 100,000 words while maintaining a full time law practice.

Hamilton biographer Ron Chernow describes the Camillus essays as another magnum opus in Hamilton’s canon. For Chernow, the essays support the claim that Hamilton was the “foremost political pamphleteer in American history.” As described by historian John Chester Miller, Camillus achieves for international relations what Pubilus and the Federalist Papers accomplished for domestic affairs.

According to historian Broadus Mitchell, Hamilton “placed every feature of the treaty in a just light as it bore upon the interests of this country.” Mitchell asserts that “Jay’s Treaty would probably not have been approved without the education of the public in Camillus’ persuasive expositions.” Alexander Hamilton, A Concise Biography (1976).

Jefferson and Madison easily recognized the authorship of their rival, leading Jefferson to remark that Hamilton was writing an “Encyclopedie” on international affairs, “according to his custom.” Despite describing the Camillus essays in a letter to Tench Cox on September 10, 1795 as “too obstinate to be twisted by all his sophisms into a tolerable shape,” Jefferson nevertheless implored Madison “[f]or god’s sake take up your pen, and give a fundamental reply to Curtius & Camillus.” Click here for a link to Jefferson’s September 21, 1795 letter to Madison.

The unpopular Jay’s Treaty galvanized the Democratic Republicans into opposition. According to historian Joseph Ellis, Jay’s Treaty succeeded in inflaming “all of Jefferson’s deepest fears and most abiding hatreds.” In American Sphinx, Ellis explains that for Jefferson, Jay’s Treaty “was a repudiation of the Declaration of Independence, the Franco-American alliance, the revolutionary movement sweeping through Europe and all the political principles on which he had staked his public career as an American statesman.”

Hamilton responded to the fierce rhetoric of Democratic Republican opponents of Jay’s Treaty by formulating a methodical and comprehensive defense, exhaustively covering all twenty-eight sections of the treaty. The essays were published under the title “The Defence” by “Camillus,” the name of a Roman general and statesman.

According to the Greek historian Plutarch, the historical figure Marcus Camillus was a hero of the 4th Century B.C. who is depicted as restoring Rome after it was sacked by the Gauls. Click here for a link to Plutarch’s Lives. The Roman historian Titus Livy recognized Camillus as the second founder of Rome. According to Plutarch’s depiction, Camillus was a self-made man of wisdom, moderation and honor, all of which traits were no doubt appealing to Hamilton. Camillus was dedicated to rule of law under the Roman Senate and never attempted to usurp power. Camillus was accused of theft and exiled but eventually vindicated when we was recalled to return and save Rome.

Hamilton biographer Ron Chernow describes the fearless Camillus as a perfect symbol for Hamilton. Camillus was a Roman general who was “a wise, virtuous man who was sorely misunderstood by his people, who did not see that he had their highest interests in his heart.” Just like Hamilton was attempting to do, Camillus was not afraid to express unpopular truths. The fact that Camillus rescued Rome from the Gauls (the ancestors of the French) is yet another historical similarity not missed on Hamilton.

Hamilton’s objectives when writing the Camillus essays included 1) defending the wisdom and constitutionality of Jay’s Treaty, 2) providing a detailed analysis of all twenty-eight Articles of Jay’s Treaty (beginning with “The Defence No. VI”), 3) refuting the arguments of Democratic Republican polemicists, 4) preserving his financial program which would be disrupted by hostilities with England, and 5) avoiding unnecessary bloodshed.

On balance, the Camillus essays were an honest and sober assessment of Jay’s Treaty from the perspective of America’s national interests. The dispassionate essays thoroughly explore the advantages and disadvantages of the treaty, provision-by-provision. In many ways the essays read as if Hamilton was preparing a legal brief for the Supreme Court.

In writing the Camillus essays Hamilton quoted a rich variety of legal sources including the German philosopher and economist Pufendorf (Of the Law of Nature and Nations), the French jurist Barbeyrac (The Rights of War and Peace), the Dutch jurist Grotius (The Rights of War and Peace; On the Freedom of the Seas) and the Swiss lawyer Vattel (The Law of Nations). For a fascinating inside view of Hamilton’s personal copy of Grotius’ classic treatise, click here.

While these names are not necessarily recognized by modern audiences, they were leading authorities for enlightenment thinkers. For example, Hugo Grotius is depicted on the north wall frieze at the U.S. Supreme Court with such leading law givers as Blackstone, Justinian, and John Marshall. Grotius is one of only 23 marble portraits hanging over the gallery doors of the Chamber of the House of Representatives, which honors historical figures who established the principles underlying American law, including Moses, Napoleon and Jefferson.

The marble relief portrait of Hugo Grotius above is located in the Galley of the House of Representatives. The north frieze of of the U.S. Supreme Court is pictured below.

The marble relief portrait of Hugo Grotius above is located in the Galley of the House of Representatives. The north frieze of of the U.S. Supreme Court is pictured below.

Washington seeks Hamilton’s expert opinion: When the treaty was only narrowly approved by the Senate in June of 1795, President Washington was unsure whether he should sign it. The reluctant President asked Hamilton, who was now in private practice, for his opinion. As he was known to do, Hamilton responded with a Hamiltonian exegesis of the treaty. Hamilton approved of the first ten articles and was critical of articles 12 and 18. Ultimately, Hamilton concluded that the Treaty was in America’s best interest.

Ron Chernow tells the story of the exchange between Washington and Hamilton, as only Chernow can:

Fully aware that the Jay Treaty was bound to be unpopular among Republicans, Washington at least wished to be convinced of its merits in his own mind and know how to defend it. On July 3, he had sent to Hamilton a letter marked “Private and perfectly confidential,” asking him to evaluate the treaty. He laid on the flattery pretty thick, praising Hamilton for having studied trade policy “scientifically upon a large and comprehensive scale.” Washington apologized for distracting Hamilton from his law practice and said he should refuse the request if he was too busy. Washington must have smiled as he wrote this, knowing Hamilton would deliver a formidable critique at this earliest opportunity. Indeed, on July 9, 10, and 11, Hamilton shipped to Washington, in three thick chunks, a detailed analysis of the treaty.

Chernow further describes that Washington was thunderstruck when he received Hamilton’s extensive handiwork dated July 9 and 10. Washington offered his “sincere thanks” for Hamilton’s observations which had “afforded me great satisfaction.” In his July 13 letter reply, Washington noted that he was in the very process of sending additional questions for Hamilton’s review when Hamilton’s letter of July 11 arrived and “was put into my hand.”

Hamilton explained that “the greatest interest of this Country in its external relations is that of peace. The more or less of commercial advantages which we may acquire by particular treaties are of far less moment. With peace, the force of circumstances will enable us to make our way sufficiently fast in Trade. War at this time would give a serious wound to our growth and prosperity.” In Hamilton’s view the national interest was best served by another decade of prosperity, which would buy time.

After analyzing each article of the treaty for Washington, Hamilton concluded that “since there are no improper concessions on our part but rather more is gained than given—it follows that it is the interest of the U States that the Treaty should go into effect.”

Click here for Hamilton’s Remarks to Washington written July 9-11, 1795, which would serve as the outline of for the Camillus essays.

The Defense No. I: The first installment of Hamilton’s Camillus essays, The Defense No. I, was published on July 22, 1795. Hamilton formulated a bold strategy to reverse the hostile public opinion against Jay’s Treaty. As he had done before, he decided to publish his columns deep behind enemy lines in the avowedly pro-Republican paper The Argus. Doing so was also a frontal assault against fellow New Yorker Robert Livingston’s Cato essays, which were published in the same paper. Of course, articles assailing and defending the treaty were republished nationally by other papers.

Hamilton began the defense by pointing out that it was important to view Jay’s Treaty on the basis of its intrinsic merits rather than irrational passions and misconceptions. Doing so was critical because “irreconcilable” opponents of the constitution “embittered in their animosity, in proportion to the success of its operation,” were searching for opportunities to discredit the government. “It was to be expected, that such men, counting more on the passions than on the reason of their fellow citizens…would be disposed to make an alliance with popular discontent, to nourish it, and to press it into the service of their particular views.”

Hamilton’s first essay, The Defence No. I, also laid out the transparent political motivations in play behind the scenes. He identified Mr. Adams, Mr. Jay and Mr. Jefferson as the three most prominent potential successors to President Washington. “No one can be blind to the finger of party spirit,” in light of the “systematic pains which have been taken to impair the well earned popularity” of Mr. Jay. Hamilton found it remarkable that toasts on the Fourth of July that were critical of Jay’s Treaty were “uniformly coupled with complements to Mr. Jefferson.” Thus demagoguery was the “evident design” and “political source of opposition to the treaty.”

On the merits, Hamilton argued that Jay’s Treaty made “no improper concessions to Great Britain” and that “the too probable result of a refusal to ratify is war, or what would be worse, a disgraceful passiveness under violations of our rights, unredressed and unadjusted.”

Hamilton next proceeded to defend the treaty one provision at a time, noting that some of the provisions had time limits of twelve years or until the end of the war between Britain and France. For Hamilton, his key objective was to avoid unnecessarily hostilities. “If we can avoid war for ten or twelve years more, we shall then have acquired a maturity which will make it no more than a common calamity, and will authorize us in our national discussions to take a higher and more imposing tone.” Hamilton was well aware that in the 1790’s America had no navy and the army consisted of only approximately 500 troops. From Colony to Superpower, U.S. Foreign Relations Since 1776, George C. Herring (2008). The Continental Navy’s last ship, the frigate Alliance, was sold in 1785. Thus, the only naval capability possessed by the United States in the 1790’s was the very limited Revenue Cutter Service, which was forerunner of the Coast Guard. Click here for a discussion of the Act Creating the Revenue Cutter Service in 1790.

Hamilton concluded the first Camillus essay by laying out almost a dozen points that he hoped to “demonstrate satisfactorily in the course of some succeeding papers” including the following:

1. That the treaty adjusts in a reasonable manner the points in controversy between the United States and Great-Britain, as well those depending on the inexecution of the treaty of peace, as those growing out of the present European war.

2. That it makes no improper concessions to Great-Britain, no sacrifices on the part of the United States.

3. That it secures to the United States equivalents for what they grant.

4. That it lays upon them no restrictions which are incompatible with their honour or their interest.

5. That in the articles which respect war, it conforms to the laws of nations.

Reaction to Camillus: After the publication of the first Camillius essay (Defence No. I), George Washington wrote to Hamilton on July 29, 1795 expressing praise for the first Camillus column:

I have seen with pleasure that a writer in one of the New York papers, under the signature of Camillus, has promised to answer-or rather to defend the treaty which has been made with Great Britain. To judge from this work from the first number, which I have seen, I auger well of the performance; and shall expect to see the subject handled in a clear, distinct and satisfactory manner.

One metric for the success of the Camillus essays was the fact that Camillus was repeatedly quoted in the House of Representatives during the funding debate. Annals of Congress in April of 1796. Another indication of Hamilton’s success is the fact that The Argus, which was not friendly to the Washington administration, announced on November 3, 1795 that it was limiting the space for Hamilton’s columns:

“The Defence, No. XXII, is received, but must give way to more Local matter…. A number of our subscribers having complained of the ‘imposition’ of so many lengthy columns from Camillus, the Editor conceives himself obliged to restrict him to only six columns per week in future, instead of from 8 to 12 as heretofore.”

The remaining Camillus essays, Nos. XXII–XXXVIII, were therefore published by Hamilton in another paper, The New York Herald.

For average Americans who remained hostile to Britain and were increasingly outraged about the abuses of the British navy, historian John Miller describes Hamilton’s ready response: “France was the one country to which Americans were drawn by gratitude and sympathy – therefore they must be especially on their guard against permitting their purely emotional bias towards France to divert them from the course of national self-interest.”

The Camillus project successfully accomplished Hamilton’s objectives. Jefferson famously paid Hamilton a passive aggressive complement that reflected Jefferson’s respect for Hamilton’s abilities, although he disagreed with Hamilton’s conclusions. In a letter dated September 21, 1795 to Madison, Jefferson acknowledged that “Hamilton is really a colossus to the anti-republican party-without numbers, he is an host within himself.”

President Washington signed Jay’s Treaty on August 18, 1795, after the publication of the eighth Camillus essay. As described in prior posts, the House narrowly voted to fund Jay’s Treaty in April of 1796.

For historian John Chester Miller, an overriding theme of the Camillus writings was the pursuit of national interests and avoiding the seductions of foreign entanglements. Alexander Hamilton and the Growth of the New Nation (John Chester Miller, 2004). These themes would subsequently be reflected in George Washington’s Farewell Address (which was co-written by Alexander Hamilton). The historic Farewell Address will be discussed in a future post.

Post script: The use of pseudonyms was commonplace among the founding generation. The device enabled writers and their subjects to preserve their sense of honor and dignity when attacked (or attacking) behind a pen name. All told, Alexander Hamilton compiled an impressive list of pseudonyms over his career. By far the most famous of Hamilton’s identities was Publius which he shared with the other co-authors of the Federalist Papers, Jay and Madison. In Hamilton’s Letters from Phocion he vigorously defended the rights of loyalists and Tories. Other nom de plumes used by Hamilton included: The Continentalist, Metellus, Catullus, Tully, Horatius, Titus, Manlius, Pericles, A Friend to America, Pacificus, Americanus, and An American.

Benjamin Franklin, who was a publisher with a sense of humor, wrote under the nom de plume Richard Sanders (Poor Richard), Silence Dogood, Alice Addertongue, Fanny Mournful, Obadiah Plainman, and the unforgettable Busy Body. Sam Adams wrote under approximately twenty-five pen names including Populus, An American, A Son of Liberty, and “Vindex the Avenger.” His cousin, John Adams was Novananglus, Sui Juris, and Humphrey Ploughjogger.

It is for good reason that journalist and author Eric Burns describes the “golden age of America’s founding” as the “gutter age of American reporting.” Eric Burns, Famous Scribblers, The Founding Fathers and the Rowdy Beginnings of American Journalism, Eric Burns(2006). According to Ron Chernow, the use of anonymous attacks “permitted extraordinary bile to seep into political discourse, and savage remarks that might not otherwise have surfaced appeared regularly in the press.”

House Debates over Funding Jay’s Treaty in April of 1796 (Annals of Congress)

Introductory Note to the Camillus Essays (Founder’s Archives)

The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, Vol. XVIII, edited by Harold Syrett (1973)

The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, Vol. XIX, edited by Harold Syrett (1973)

Classical Pseudonyms as Rhetorical Devices in Response to Jay’s Treaty, Nancy Anne Hill (2014)

Enjoyed reading this, very good stuff, thank you.