Jay’s Treaty – The United States’ first and arguably most controversial treaty

(signed in London 11/19/1794; ratified by the Senate on 6/24/1795; signed by President Washington 8/14/1795)

Jay’s Treaty with Britain was arguably the most controversial treaty in American history. The unpopular agreement was the United States’ first treaty under the new Constitution of 1787. With the benefit of hindsight, historians recognize the wisdom of the decision by Washington, Jay and Hamilton to make peace with England and avoid becoming entangled in European confrontations.

While Jay’s Treaty partially resolved hostilities between America and England in the last decade of the 18th Century, the battle over the treaty’s ratification created bitter divisions that contributed to the creation of America’s first political parties. George Washington never forgave James Madison – or spoke to him again – after the deep rift that was created by the political battle over the treaty. Even after the treaty was ratified by the Senate, the battle to fund the treaty continued in the House of Representatives. By refusing to turn over private diplomatic communications to the House, Washington established the doctrine of executive privilege which continues to be debated today.

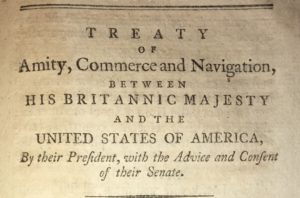

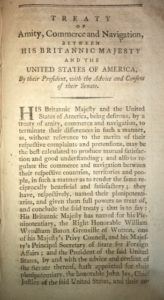

Jay’s Treaty (also called the “Jay Treaty”) was formally known as the “Treaty of Amity Commerce and Navigation, between His Britannic Majesty; and The United States of America,” but was widely referred to by the name of Supreme Court Chief Justice John Jay who negotiated the treaty in London in 1794.

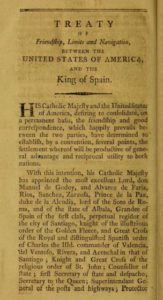

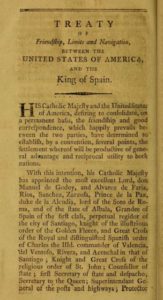

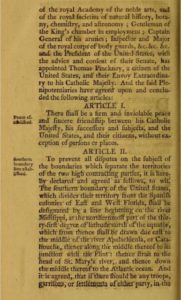

Despite the controversy that it created, Jay’s Treaty is now widely acknowledged by historians to be one of the most important treaties in American history. While Jay’s Treaty was not fully appreciated at the time, a collateral benefit was the fact that the treaty directly led to the favorable resolution of pending disputes with Spain. Fearing an Anglo-American challenge to Spanish interests in North America, Spain agreed to nearly everything sought by American negotiator Thomas Pinckney the following year. Thus, Jay’s Treaty is properly viewed together with the Treaty of San Lorenzo (Pinckney’s Treaty) under which Spain agreed to American navigation of the Mississippi and the northern border of Florida along the 31st parallel. Copied below are the first pages of Jay’s Treaty and Pinckney’s Treaty.

According to historian Joseph Ellis, Jay’s Treaty presented the “greatest crisis of Washington’s presidency.” Notwithstanding the furor created by the treaty, it was a “landmark in shaping American foreign policy,” even if it represented a “repudiation of the Franco-American alliance of 1778, which had been so instrumental in gaining French military assistance for winning of the American Revolution.”

As summarized by Joseph Ellis in the book Founding Brothers:

While the specific terms of the treaty were decidedly one-sided in England’s favor, the consensus reached by most historians who have studied the subject is that Jay’s Treaty was a shrewd bargain for the United States. It bet, in effect, on England rather than France as the hegemonic European power of the future, which proved prophetic. It recognized the massive dependence of the American economy on trade with England [and] linked American security and economic development to the British fleet, which provided a protective shield of incalculable value throughout the nineteenth century. Most importantly, it postponed war with England until America was economically and politically more capable of fighting one.

Washington himself explained that biding time would only strengthen America if war would later be necessary against England or any other power: “Twenty years peace with such an increase population and resources as we have a right to expect; added to our remote situation from the jarring power, will in all probability enable us in a just cause, to bid defiance to any power on earth.” Click here for a link to Washington’s May 1, 1796 letter to Charles Carroll explaining his reasons for supporting Jay’s Treaty.

Background following the Revolutionary War: The Treaty of Paris that ended the Revolutionary War in 1783 was viewed by many in Britain as an unnecessary capitulation to America. Prime Minister Shelburne, who negotiated the Treaty of Paris, decided that conciliation with the Americans was preferable to continued hostilities with the former colonies. Lord Shelburne believed in the liberal free trade principles of Adam Smith. As described by historian Jerald Combs, Shelburne hoped to bind America to England “substituting for the colonial ties now seared the silken threads of commerce.” The Treaty of Paris is copied below.

Nevertheless, almost as soon as the terms of the Treaty of Paris became public in early 1783, many in Britain were astonished by the generous concessions given to the Americans. For example, even British newspapers that generally supported the Shelburne administration declared that, “[t]he terms granted to the Rebellious colonies are hardly to be mentioned: our Language does not furnish Expressions adequate to so create a Disgrace.”

Viewed from the British perspective, the 1783 Treaty of Paris shamefully abandoned British loyalists who had supported King George. The Treaty of Paris lacked any enforceable obligation to obtain the return of confiscated loyalists property. Rather, the Americans merely pledged that Congress would recommend to the states that loyalist property should be returned. Critics also complained that Britain’s Indian allies, who had sided with the British during the Revolutionary War, had likewise been abandoned and left at the mercy of the former colonies.

Opponents further complained that Britain had surrendered too much land along the Canadian border, including the fertile triangle of land between the Ohio and Mississippi rivers. Americans were also granted liberal access to the fisheries off the coast of Newfoundland. Because Britain agreed to surrender the frontier forts along the the Great Lakes, Canadians were fearful that they would be defenseless against American invasion. These complaints led to the fall of the Shelburne administration in 1784. Lord Shelburne is pictured below. Jay’s Treaty would be negotiated a decade later against this backdrop of British hostility.

Growing tensions in 1789: After the new U.S. Constitution was ratified, the French Revolution shook Europe. While Americans were sympathetic with France’s turn toward republicanism, Great Britain was America’s biggest trading partner. Americans generally welcomed the French Revolution as the logical continuation of the American Revolution. Yet, by 1793 it was becoming clear that the French Revolution was increasingly destabilizing and violent, when King Louis XIV was executed and France declared war on England, Spain and Holland.

Rather than picking sides, President Washington determined that the United States would not ally itself with either England or France. Washington declared a policy of neutrality and “conduct friendly and impartial toward the belligerent powers.”

The French believed that the United States was obligated to assist France based on the Franco-American Alliance of 1778. Taking the advice of Alexander Hamilton, Washington concluded that America was not bound to aid France. Hamilton reasoned that the overthrow of the French monarchy had replaced the former French government and justified the suspension of any American treaty obligations to France. Hamilton also convinced Washington that America’s Alliance with France was merely a defensive commitment. Since France had attacked its neighbors, Hamilton argued that the 1778 Alliance did not apply.

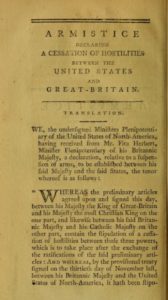

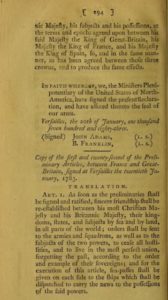

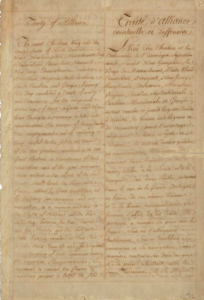

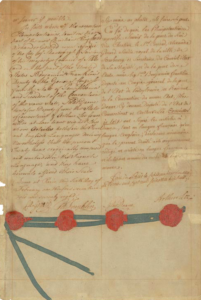

Copied above is the Treaty of Alliance of 1778 between America and France, signed by Benjamin Franklin. Click here for a link to the Treaty of Alliance, otherwise known as the Franco-American Treaty.

Copied above is the Treaty of Alliance of 1778 between America and France, signed by Benjamin Franklin. Click here for a link to the Treaty of Alliance, otherwise known as the Franco-American Treaty.

In 1794 Congress passed the Neutrality Act of 1794, which made it a crime for American citizens to participate in the French Revolutionary War, or use American soil as a base of operations for either Britain or France. Click here for a link to the Neutrality Act of 1794, officially titled an “Act in Addition to the Act for the Punishment of certain Crimes against the United States” (which never actually uses the term “neutrality”).

In 1794, when Washington and Hamilton decided to dispatch Jay to London, the country faced growing tensions with England. The U.S. was simultaneously engaged in hostilities with the Indians in the Northwest Territory, who were being agitated by British agents in the frontier. Renouncing the agreed-upon border between the U.S. and Canada, Britain’s governor in Quebec predicted a new Anglo-American war “within a year.”

As described by historian Jerald A. Combs, the British had a low estimate of American power. In the decade following the American Revolution the British government decided to hold its frontier posts and militarily supported the Native Americans, in an effort to contain American territorial expansion. Britain didn’t contemplate the reconquest of America, but was seeking to “maintain what it regarded as the proper status quo between itself and America.”

The contents of Jay’s Treaty: Jay’s Treaty provided as follows:

- Required withdrawal of British forces from six forts on the northwestern frontier on or before June 1, 1796 thereby allowing undisputed American sovereignty over the entire Northwest;

- Created joint commissions to adjudicate pre-Revolutionary War debts, border disputes in the NorthEast, and compensation for British maritime seizures;

- Allowed American ships to enter British ports in the British East Indies on a non-discriminatory basis;

- Permitted American ships not exceeding 70 tons to trade with the British West Indies, provided the U.S. ships did not trade cotton, sugar, coffee, or molasses;

- Granted most favored nation status to British imports, without equivalent status for American imports to Britain;

The treaty did not:

- Require the British to pay compensation for slaves seized during the Revolutionary War;

- End the practice of impressment of sailors; and

- Fully protect American neutral rights and the principle of freedom of the seas.

Democrat-Republican critics of Jay’s Treaty believed that too few American interests were protected. For example, the only immediate British concessions were the surrender of the Northwestern forts (which had already been agreed to in 1783) and a commercial treaty with Great Britain that restricted full U.S. commercial access to the British West Indies. All other disputed issues were subject to arbitration, including the Canada-Maine border, compensation for pre-revolutionary debts, and British seizures of American ships. Under a watered down version of neutral rights, Britain was empowered to seize U.S. goods bound for France (if it paid for them) and could confiscate French goods on American ships (without limitation).

Jay told Washington that he achieved his primary mission of securing peace with Britain. “To do more was impossible,” he explained. Under the circumstances, Jay’s Treaty arguably represented the most the a weak and politically divided U.S. could extract from Britain.

Postscript to Jay’s Treaty: Alexander Hamilton understood that American tariffs on British imports served as the fundamental underpinning of his entire financial program. Moreover, America was more dependent on trade with Britain than Britain was on trade with America. Hamilton also recognized that growing custom revenues in the late 1790s enabled the states to lower taxes, which served to enhance the popularity the Washington administration and the new federal government.

In the years to follow American prosperity increased, at the same time that European countries engaged in costly wars. American imports of consumer goods exploded from $23,500,000 in 1790 to $63,000,000 in 1795. America ultimately became the biggest market for Britain and the British Empire in turn became the biggest American export market. American exports tripled from 1792 to 1796. After the dust settled, opposition to Jay’s Treaty subsided as Americans began to see the economic benefits of Jay’s Treaty. Eventually, the improved relationship between America and Britain would provoke retaliation from France. The resulting “Quasi-War” with France and the notorious XYZ Affair will be discussed in a future post.

The story of the contentious ratification battle over Jay’s Treaty, which crystalized the growing partisan divide between Federalists and Democrat-Republicans will be continued in Jay’s Treaty – Part II. Hamilton’s essays in support of Jay’s Treaty written under the pseudonym Camillus are discussed in Jay’s Treaty – Party III.

Additional reading:

Jay’s Treaty, Primary Documents (Library of Congress)

The Jay Treaty: Political Battleground of the Founding Fathers (Jerald A. Combs, 1970)

American Politics in the Early Republic: The New Nation in Crisis, James Roger Sharpe (1993) at 119.

Jay’s Treaty: A Study in Commerce and Diplomacy, Samuel Flagg Bemis (1962)

“Impeach President Washington!”, American Heritage Magazine, Michael Beschloss, Fall 2017

Jay’s Treaty (State Department, Office of the Historian)

Pinckney’s Treaty/Treaty of San Lorenzo (State Department, Office of the Historian)

Treaty of Alliance with France, 1778, primary documents (Library of Congress)

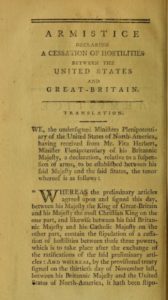

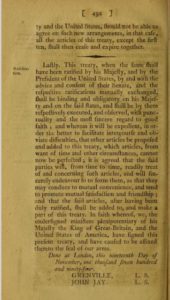

Pictured below are images from the Folwell edition of the Laws of the United States (1796), edited by Zephaniah Swift.

Pictured below is the Treaty of Paris:

Pictured below is the Jay’s Treaty:

Pictured below is Pinckney’s Treaty: