The Prohibitory Act of 1775

(England’s virtual Declaration of War against the Colonies which precipitated the Declaration of Independence)

[16 Geo. III, Ch. 5, Dec. 22, 1775]

The Prohibitory Act: The Prohibitory Act of 1775 was a virtual declaration of war by Parliament against the American colonies and a rejection of the Continental Congress’ Olive Branch Petition. The Act was adopted following the “shot heard round the world” at Lexington and Concord, as memorialized in Ralph Waldo Emerson’s 1837 poem “Concord Hymn.”

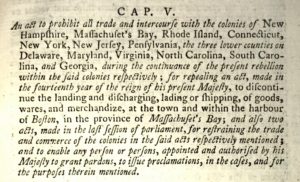

The Prohibitory Act banned “All manner of trade and commerce” and provided that any American ship found trading “shall be forfeited to his Majesty, as if the same were the ships and effects of open enemies.” (16 Geo. III, c. 5). The Prohibitory Act doubled down on the earlier New England Restraining Act of March, 1775 (15 Geo. III c. 10), which restricted trade by the New England colonies exclusively with England and denied access to the North Atlantic fisheries off the coast of Newfoundland.

The avowed purpose of the Prohibitory Act was to hobble the American economy with a wartime embargo that prohibited all trade with any country. Ultimately the Act provided the Continental Congress with the excuse that John Adams had been waiting for to sever all allegiance to King George III. John Adams considered the Act “the complete dismemberment of the British Empire” that effectively “makes us independent,” seven months before the Declaration of Independence.

Continental Congress’ dual-track strategy: In the pivotal year of 1775 the relationship between the colonies and their mother country was being shaken to its core. The Second Continental Congress had adopted a two-pronged strategy to simultaneously accommodate the objectives of moderates seeking reconciliation with England and the radical patriots clamoring for independence. The moderate “reconciliationists” were led by John Dickinson from Pennsylvania who wanted to exhaust all possibilities of peaceful compromises with King George. By contrast, John Adams was one of the leading radical patriots clamoring for the opportunity to declare independence, which he privately deemed inevitable in 1775.

The Second Continental Congress plotted a middle course between both moderate and radical positions, but would be overtaken by events on the ground. In particular, 1) the Prohibitory Act, 2) King George III’s August 22, 1775 proclamation declaring the Americans to be in a state of open rebellion, and 3) the publication of Thomas Paine’s pamphlet Common Sense provided the final motivation for the Declaration of Independence.

Olive Branch Petition: John Adams described the Olive Branch petition as an earnest effort “to keep open the door of reconciliation, to hold the sword in one hand and the olive branch in the other.” As described by Adams in a June 10, 1775 letter to Moses Gill, the Second Continental Congress was moving simultaneously with two parallel tracks in 1775:

to prepare for a vigorous defensive War, but at the Same Time to keep open the Door of Reconciliation – to hold the Sword in one Hand and the Olive Branch in the other – to proceed with Warlike Measures, and conciliatory Measures Pari Passu.

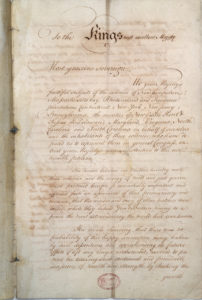

In a final effort to avoid further hostilities on July 5, 1775 the Second Continental Congress decided to appeal directly to King George III with John Dickinson’s Olive Branch Petition. Necessarily acknowledging that contending armies were already in the field, the petition described the war that had already begun as “a controversy so peculiarly abhorrent to the affections of your still faithful colonists.” Nevertheless, the petition insisted that Britain had effectively “compelled us to arms in our own defense.”

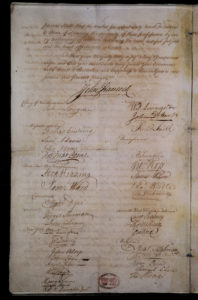

The petition was based on the fiction that King George did not support Parliament’s crackdown on the colonies and that he would intervene on their behalf. While the petition was the handiwork of John Dickinson of Pennsylvania, other signatories to the Olive Branch petition covered the political spectrum and included John Hancock, John Adams, Roger Sherman, John Jay, Thomas Jefferson, and Benjamin Franklin. John Hancock’s prominent signature is particularly noticeable, as would also be the case on the Declaration of Independence. Click here for a link to the NY Public Library’s copy of the Olive Branch Petition, which is pictured below. Click here for the text of the Olive Branch Petition.

As the Second Continental Congress was debating the creation of the Continental Army in May of 1775, Dickinson advocated for petitioning King George with what he characterized as a “Measure of Peace.” To Adams, however, the exercise was a “Measure of Imbecility” since in October 1774, the First Continental Congress had previously petitioned King George. Adams and Ben Franklin feared that doing so again would risk appearing weak. “It is a true old saying,” Franklin observed, “that make yourselves sheep and the wolves will eat you.”

In the summer of 1775 John Adams recognized that the colonies were not yet ready to declare independence. In a letter to Joseph Warren dated July 6, 1775 Adams explained his thinking that the colonies must “dissolve all Ministerial Tyrannies, and Custom houses, set up Governments of our own,….confederate together like an indissoluble Band, for mutual defence and open our Ports to all Nations immediately.” At the end of the letter Adams admitted that this was his plan that he had “aimed at promoting from first to last; But the Colonies are not yet ripe for it.”

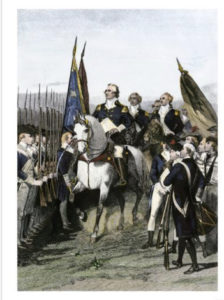

Nevertheless, the two track approach allowed the thirst for independence to ripen on the vine with time. As recognized by Adams, “We cannot force Events. We must Suffer People to make their own Way in many Cases.” Adams June 10, 1775 letter to Moses Gill. While attempting reconciliation, the Second Continental Congress established the Continental Army on June 14, 1775, and nominated George Washington to lead it. The unified and pragmatic Congress also opened American ports to trade in violation of British law, and considered establishing a national currency. The Second Continental Congress also urged the colonies to prepare for war by equipping and training their militia, while the final diplomatic initiative attempted to pursue reconciliation.

Copied below is an engraving of General Washington taking command of the Continental army around Boston.

As described by historian Joseph Ellis, “[i]n the meantime, the radicals and moderates in the congress could work together, both sides acknowledging the complementary legitimacy of the other. The hobbyhorse of the moderates was a compromise that proposed an immediate cessation of hostilities and a recognition of royal authority, but not parliamentary authority, over the colonies.”

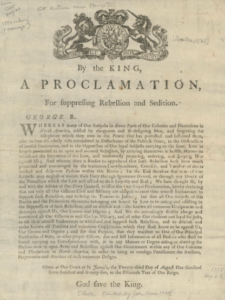

On August 23, 1775 King George refused to accept the Olive Branch Petition and issued a Royal Proclamation which declared the colonies to be in a state of “open and avowed rebellion.” A copy of the Royal Proclamation is pictured above. On September 1, 1775, the respected former governor of Pennsylvania, Richard Penn (grandson of William Penn the founder of Pennsylvania), along with Arthur Lee, attempted to present the Olive Branch Petition to King George, but they were forced to leave the Petition with the Earl of Dartmouth.

Less than three months later, following the Battle of Bunker Hill, Parliament and King George responded with the Prohibitory Act. The harsh Act made American ships “fair game for the Royal Navy” and attempted to starve the colonies into submission as Britain mobilized additional military forces. Under the laws of war, the Prohibitory Act’s blockade was an act of war.

Impact of the Prohibitory Act: The Continental Congress considered the Act a declaration of economic warfare. In response the Second Continental Congress passed the Privateering Resolution on March 23, 1776 declaring that “whereas the parliament of Great Britain hath lately passed an Act, affirming these colonies to be in open rebellion, forbidding all trade and commerce with the inhabitants thereof… [It is] resolved that all ships and other vessels… belonging to any inhabitant or inhabitants of Great Britain, taken on the high seas … shall be deemed and adjudged to be lawful prize.”

Upon learning of the Prohibitory Act John Adams (pictured above) celebrated that the die had been cast. In a letter to Horatio Gates dated March 23, 1776 Adams wrote:

“I know not whether you have seen the Act of Parliament call’d the restraining Act, or prohibitory Act, or piratical Act, or plundering Act, or Act of Independency, for by all these Titles is it call’d. I think the most apposite is the Act of Independency, for King Lords and Commons have united in Sundering this Country and that I think forever. It is a compleat Dismemberment of the British Empire. It throws thirteen Colonies out of the Royal Protection, levels all Distinctions and makes us independent in Spight of all our supplications and Entreaties.

It may be fortunate that the Act of Independency should come from the British Parliament, rather than the American Congress”

According to Joseph Ellis, Adams never seriously believed that conciliation stood a chance of success in 1775. Years later when it was suggested that he did more than anyone else to promote American independence, Adams declined the honor, which he said belonged to King George III.

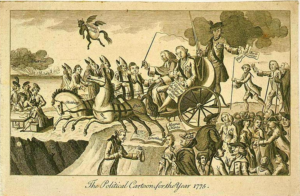

The political cartoon pictured below depicts King George riding over the Magna Carta and the English constitution in a carriage driven by two horses labeled pride and obstinacy.

The Act instituted a full blown embargo of all American ports. Unlike the earlier Restraining Acts, the Prohibitory Act was directed at all 13 colonies. Thus, the Prohibitory Act converted the Restraining Act, which was also known as the New England Trade and Fisheries Act or the New England Restraining Act (15 Geo. III c. 10) into a complete embargo of the colonies. The Act also permitted impressment of captured American crews and turned American ships into “fair game for the Royal Navy.”

In hindsight, the Act effectively ended any chance for reconciliation and marked the point of departure in the tit for tat exchange between the Americans and King George.

The Act passed in the House of Commons on December 11 by a vote of 112 to 16. It was passed by the House of Lords on December 21 by a vote of 48 to 12.

King George’s speech to Parliament coincidentally arrived at Philadelphia on January 10, 1776, the same day that the first thousand copies Common Sense by Thomas Paine were published.

Further reading:

Link to the Olive Branch Petition

Link to Proclamation of Rebellion

Timeline of the American Revolution

Kevin Phillips, 1775: A Good Year for Revolution

What was the Olive Branch Petition? (History of Mass blog)

S.E. Forman, Our Republic: A Brief History of the American Republic (1922)

Bob Ruppert, Reconciliation No Longer an Option (Journal of the American Revolution)

Black, Jeremy. George III: America’s Last King. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006.

Middlekauff, Robert. The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763–1789. Rev. ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005

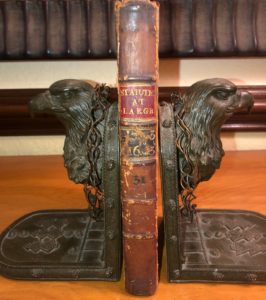

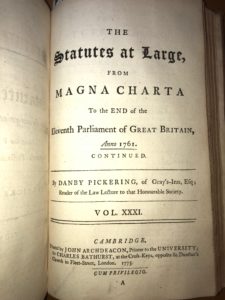

Copied below are pictures of the Prohibition Act and Restraining Act of 1775, published in Danby Pickering’s Statutes at Large, Volume XXXI (1775):

Copied below is a picture of the Prohibition Act of 1775: