Significance of Newly Discovered Hamilton Records

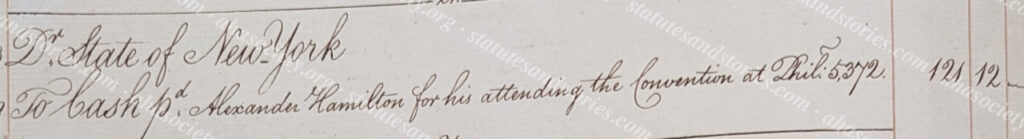

Recently uncovered records in the New York State Archives from 1787 and 1788 shed new light on our understanding of this formative period in American history. Importantly, these ledgers authoritatively demonstrate that Alexander Hamilton and his co-delegates Robert Yates and John Lansing, Jr., were compensated by the state of New York for their time at the Constitutional Convention. These discovery will be discussed in pending articles in the New York Archives Magazine.

The purpose of this blog post is to discuss the significance of these newly revealed records. For prior articles reporting these discoveries click here for a discussion of Hamilton’s reimbursement for the Annapolis Convention & Constitutional Convention and here for Yates/Lansing’s reimbursement for the Constitutional Convention.

In other words, this post is intended to address the underlying question, “So what? Why does it matter that New York delegates Hamilton, Yates and Lansing were paid for their work in Philadelphia?” As described below, we are only beginning to understand the important implications of these and other records which have not yet been studied by historians.

Why are these records significant?

While their work in Philadelphia was controversial, there is no doubt that the New York delegates diligently worked on their assigned task. As described by Tom Ruller, New York’s State Archivist, the recently discovered records of payments to Hamilton, Yates and Lansing signify that the new state governmented abided by its contractual obligations. New York’s three delegates were selected by the New York Legislature, which officially voted to send them to Philadelphia to represent the State of New York. It thus makes sense that they should be paid/reimbursed for their expenses and time.

Yet, the internally conflicted New York delegation stands out among the other states based on its vocal opposition to Constitution. Famously, Alexander Hamilton was the only delegate from New York to sign the Constitution. In early July Yates and Lansing left the Convention in protest to the Virginia Plan. Hamstrung by his co-delegates, Hamilton had already departed Philadelphia in late June. He briefly reappeared in Philadelphia on August 13. Hamilton returned on September 6 and worked through September 17, the final day of the Convention.

It was thus an open question as to whether New York would compensate its delegates for their work. Indeed, it is conceivable that New York’s Anti-federalists might have tried to repudiate Hamilton’s signature on the Constitution. One way to have done so is by censuring him for disregarding his instructions or refusing to pay him.

Controversy over the Convention’s work

When thirty-eight delegates to the Constitution Convention lined up on 17 September 1787 to sign the Constitution they knew that their work was controversial. Unanimous consent by all thirteen states was required for amendments to the Articles of Confederation. This high bar would have been nearly impossible to achieve since Rhode Island failed to even send a delegation to Philadelphia. Likewise, two of the three New York delegates departed Philadelphia to protest the arguably unauthorized actions that the Convention was taking.

Robert Yates and John Lansing, Alexander Hamilton’s co-delegates from New York, objected when it became clear that the Convention was prepared to replace the Articles with a new Constitution, rather than simply amending the Articles. As described by Madison’s notes on June 16, John Lansing asserted that it was “unnecessary & improper to go farther” than the moderate New Jersey Plan. Lansing argued that he was “sure” that New York “would never have concurred in sending deputies to the convention, if she had supposed the deliberations were to turn on a consolidation of the States, and a National Government” under the Virginia Plan.

When Yates and Lansing departed the Convention in protest, they were faithfully abiding with the limitations that they believed were imposed by both the Confederation Congress and the New York Legislature. According to its February 21 Resolution, Congress called for the states to send delegates to Philadelphia for “the sole and express purpose of revising the Articles of Confederation.” This limitation was specifically repeated in the February 28th instructions from the New York Legislature, unlike broader instructions by certain other states.

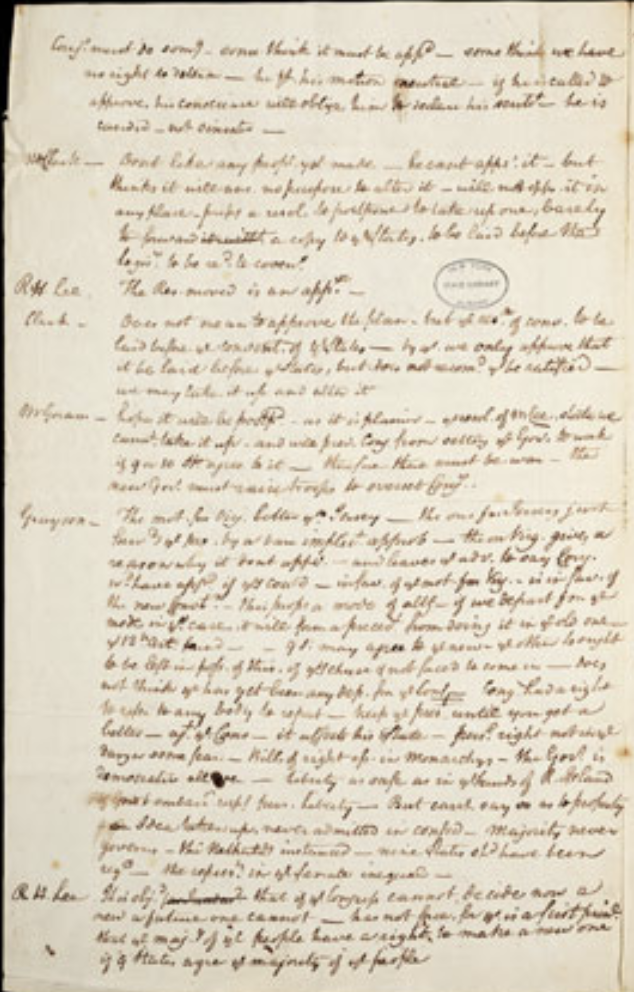

These and other objections were repeated when the Confederation Congress briefly debated the Constitution before agreeing to send it to the states for ratification. Convention Secretary William Jackson promptly delivered the Constitution to Congress on September 20. The Constitution was read aloud and “laid before the United States in Congress assembled.” When debate began on September 26, almost a third of the members of Congress in attendance had been delegates in Philadelphia. Nevertheless, the simple step of sending the Constitution to the states generated heated opposition from the emerging ranks of Anti-federalist opponents.

For example, Richard Henry Lee of Virginia was aware of George Mason’s refusal to sign the Constitution in Philadelphia, along with Mason’s detailed list of objections. On September 27 Lee moved that Congress consider amendments to the Constitution, including the addition of a Bill of Rights. For Lee, the Convention had committed “constitutional impropriety” by attempting to replace the Articles of Confederation. Not surprisingly, Lee was joined in his opposition by Robert Yates and Melancton Smith of New York.

While the Journal of Congress does not record the debates, Smith’s notes of the debates reflect passionate disagreement over the fate of the Constitution. In particular, Lee and his Anti-federalist colleagues wanted to declare that the Constitutional Convention had violated the Articles. According to Anti-federalist opponents in Congress, it had “no right to recommend a plan subverting the government” unless agreed to by 13 states. Smith’s notes also record the concern that the Constitution “proposes [to] destroy the Confederation of 13 and [to] establish a new one of 9.”

Ultimately, both sides compromised. Congress voted not to formally endorse the Constitution but simply transmit it to the states. All dissent was then stricken from the official Congressional Journal. On September 28 – only eight days after receiving the Constitution – Congress unanimously passed the following carefully worded Resolution:

Congress having received the report of the Convention lately assembled in Philadelphia.

Resolved Unanimously that the said Report with the resolutions and letter accompanying the same be transmitted to the several legislatures in Order to be submitted to a convention of Delegates chosen in each state by the people thereof in conformity to the resolves of the Convention made and provided in that case.

Interestingly, the word “Constitution” is omitted from the Congressional Resolution which merely provides for the transmittal of the Convention’s “report” to the states.

Additional questions raised by new discoveries

A host of new questions are raised by these discoveries. Set forth below are a handful of non-exhaustive questions which will be discussed over the next several months as we study this treasure trove of newly discovered records:

- Did George Clinton, New York’s Anti-Federalist governor, know of the reimbursements? Who approved the payments?

- Why did Hamilton wait unti May 19, 1788 to be reimbursed, nearly a year after he arrived in Philadelphia in May of 1787?

- Did Hamilton purposely wait for Yates and Lansing to be reimbursed on April 7 and May 2, 1788 before he submitted his request for reimbursement?

- Is there any signficance to the fact that Hamilton, Yates and Lansing each sought reimbursement before the convening of the New York ratification in Poughkeepsie?

- Why was Hamilton reimbursed for the Annapolis Convention in May of 1787 and the Constitutional Convention in May of 1788? Professor John Kaminski suggests that the May payment date was consistent with the closing of the legislative session for the year.

- How did the reimbursement process work in New York for “federal” officials, including members of Congress?

- How did New York’s lucrative tax on imports flowing through New York habor (the New York “impost”) shape its thinking? How would the proposed “federal impost” and ban on state tariffs impact New York’s finances?

Additional Reading:

On this day: September 28 (National Constitution Center)

Nation at a Crossroads (New York Historical Society)