When did the 13 colonies become the United States? When and how was the federal government formed ? As described below, the federal government did not fully take shape until the First Congress breathed life into the Constitution in 1789 by passing the foundational laws that established the Executive and Judicial branches of the federal government.

Critical dates leading to the First Congress: The colonies declared their independence from Britain in July of 1776. Independence was declared on July 2; the text of the Declaration of Independence was approved by the Continental Congress on July 4; the Declaration was finally signed on August 2.

The country’s first constitution, the Articles of Confederation, was adopted by the Continental Congress on November 15, 1777. The Articles were eventually ratified on March 1, 1781. Recognizing systemic defects with the Articles, on February 21, 1787, the Confederation Congress (also known as the “Congress of the Confederation”) called for a Constitutional Convention to amend the Articles of Confederation. Because “plan A” was increasingly recognized as a failure, it was unclear what the future of the Revolution would hold if “plan B” did not succeed.

(pictured above is a view of Federal Hall and Trinity Church looking across Wall Street in New York City where the first and second Sessions of the First Congress met in 1789 and 1790)

The Constitution was drafted in Philadelphia during the summer of 1787. On September 17, 1787 a majority of the delegates signed the final draft of the Constitution, but the Constitution required ratification by nine states to take effect. On December 7, 1787, Delaware became the first state to ratify. Ten months later, New Hampshire became the all important ninth state to ratify on July 21, 1788. The nine state threshold was only possible, however, after a compromise was reached in February of 1788 when Massachusetts and other holdout states agreed to ratify with the assurance that a Bill of Rights would be adopted.

The new federal government did not begin operations until the First Congress met in New York on March 4, 1789, on the date and location selected by the Confederation Congress. President Washington was inaugurated at Federal Hall in New York City on April 30, 1789. Even so, it is fair to say that the federal government was not fully formed until the First Congress adopted the foundational laws that fleshed out the Constitution during its first sessions from 1789 to 1791.

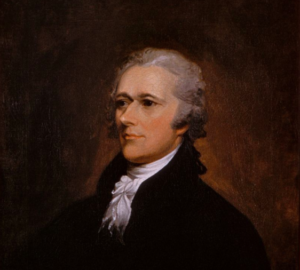

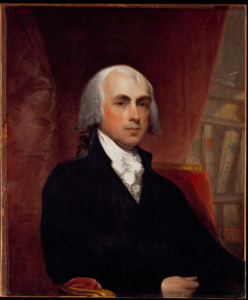

Indeed, historian Joseph Ellis argues that Lincoln had the dates wrong in the Gettysburg Address because the “nation” was not brought fourth “four score and twenty years” from 1863. Rather, the Articles of Confederation were little more than a “peace pact” between sovereign states that regarded themselves as mini-nations in their own right, that mutually and voluntarily came together in a domestic version of a League of Nations. In the book The Quartet: Orchestrating the Second American Revolution, Ellis contends that four individuals were primarily responsible for the transition from confederacy into a nation: George Washington, James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and John Jay. This post tells the final leg of the story, which was consummated by the First Congress.

The First Congress (1789 – 1791): Arguably, the responsibility for the success or failure of the American Revolution now rested with the First Congress. Fortunately, the First Congress acted as a virtual second sitting of the Constitutional Convention under the leadership of James Madison and proved to be one of the most important and productive Congresses in American history.

According to Alexander Hamilton biographer Ron Chernow, “If Washington is the father of the country and Madison the father of the Constitution, then Alexander Hamilton was surely the father of the American government.” Yet, as explained by historian Fergus Bordewich in his 2016 book, The First Congress: How James Madison, George Washington, and a Group of Extraordinary Men Invented the Government:

No man contributed more to the achievements of the First Congress than James Madison. He guided debate almost single-handedly during the first two sessions, played a crucial rule in strengthening the presidency, shaped the amendments that would become the Bill of Rights, helped forge the compromise that established the seat of government…it is impossible to overrate his contribution to the Congress’s success.

When the first Congress began meeting in March of 1789, it was initiating what can only be described as experiment in democracy. The newly conceived federal system involved democracy on a scale never before attempted. Three weeks before Washington’s inauguration, James Madison introduced into the House a schedule for proposed import duties. Chernow suggests that there was no better way to proclaim the new federal government’s autonomy – and draw a stark contrast to the impotent Articles of Confederation – than proceeding first with independent sources of revenue.

By virtue of his background, Madison was uniquely qualified. Of course he had played a central role at the Constitutional Convention, was a leader at the Virginia convention, and was a co-author of the Federalist papers with Alexander Hamilton and John Jay. Recognizing this, President Washington heavily relied on Madison for advice. For example, shortly after his inauguration, Washington had asked Madison to draft a letter to Congress expressing his interest in working closely together as co-equal branches. Madison’s Congressional colleagues asked him to draft a response to Washington, not knowing that Madison was the author of Washington’s letter. As described by Chernow in his biography of Washington, “It was Madison writing to Madison. He had become the second most prominent figure in the new government.” Thus, during the early months of the first Congress, Madison served as Washington’s Congressional liaison and closest confident.

Congress was the first branch of the federal government, created by Article I the Constitution. When Congress convened for its first session in 1789 it was the only branch of government. President Washington could only be sworn in on April 30, 1789 after ballots from the Electoral College were counted by Congress.

On the agenda for the First Congress was nothing less than the establishment of the executive branch, the cabinet, and the entire federal judiciary. Of course, ratification of the Constitution had been premised on the adoption of a Bill of Rights, but without a Treasury Department and new taxes the government lacked any sources of revenue.

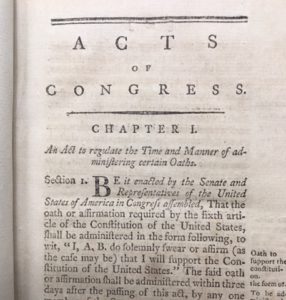

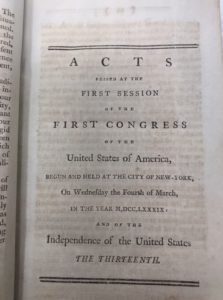

The first Act of the First Congress was passed on May 5, 1789. Rather than starting with lofty or significant legislation, the first Congress was logical and practical. Congress decided that the first order of business was the administration of oaths as required by the Constitution. Click here for a link to the Oath Act.

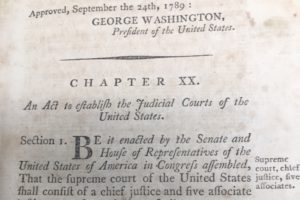

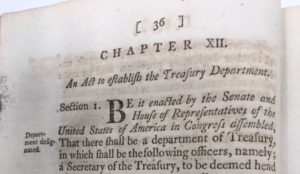

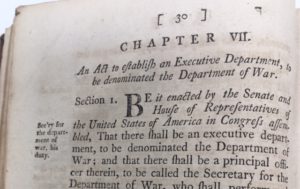

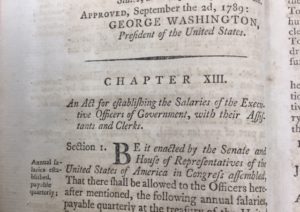

The first substantive act of Congress was the Tariff of 1789, which implemented a primary Congressional role, the power of the purse. Congress next proceeded to create the first cabinet level department, originally named the Department of Foreign Affairs, on July 27, 1789. The War Department was established in August and the Treasury Department in September. Congress rounded out the three branches of government by adopting the Act establishing the Judiciary and the Office of the Attorney General at the end of the first of three Congressional sessions, on September 24, 1789.

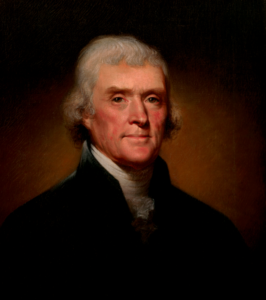

At the urging of Secretary of Treasury Hamilton, Congress passed the Funding Act of 1790 which provided for the assumption by the federal government of state debts incurred during the Revolutionary War. Copied below are portraits of Washington’s first cabinet: Secretary of Treasury Alexander Hamilton, Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, and Secretary of War Henry Knox.

Hamilton put the country on a firm financial footing with the adoption of the Duties Act of 1790 and the Whiskey Act. The collection of revenue necessitated the creation of the Coast Guard which Hamilton oversaw. Click here for a link to the Duties Act which created the Coast Guard. While Hamilton and Madison worked closely on most legislative proposals, they parted ways on the creation of the First Bank of the United States, which Jefferson and Madison believed to be unconstitutional.

Hamilton put the country on a firm financial footing with the adoption of the Duties Act of 1790 and the Whiskey Act. The collection of revenue necessitated the creation of the Coast Guard which Hamilton oversaw. Click here for a link to the Duties Act which created the Coast Guard. While Hamilton and Madison worked closely on most legislative proposals, they parted ways on the creation of the First Bank of the United States, which Jefferson and Madison believed to be unconstitutional.

The First Congress also approved the first federal public works protect, the Lighthouse Act of 1789, formally called an “Act for the Establishment and Support of Lighthouses, Beacons, Buoys, and Public Piers.” While not widely known, the first federal labor law was also adopted by First Congress in 1790. The Act for the Government and Regulation of Seamen represented a robust effort to protect the rights of sailors, who had historically been subject to exploitation by ship owners (and/or ship “masters”).

During the second and third sessions, the First Congress established copyright and patent laws, adopted the first federal criminal laws, and created a system of immigration and naturalization. Click here for a link to the Copyright Act of 1790. Click here for a link to the Crimes Act of 1790. Click here for a link to the Naturalization Act of 1790.

Less well known laws adopted by the First Congress included the Act for the Government and Regulation of Seamen (the first federal labor law) and the Lighthouse Act of 1789 (the first federal public works project). By the end of the First Congress, the location for the new capital was selected (click here for a link to the Residence Act of 1790 which provided for the permanent capital to be built in Washington, D.C., with the temporary capital to meet in Philadelphia), the census was created, and a remarkable total of 118 bills were enacted into law.

It is widely acknowledged that the defacto leader of the House during this early period was James Madison, along with Speaker of the House, Frederick Muhlenberg of Pennsylvania (who is pictured above). As described by Representative Fisher Aimes of Massachusetts, Madison was the “first man” of the House:

He derives from nature an excellent understanding … but I think he excels in the quality of judgment. He is possessed of a sound judgment, which perceives truth with great clearness, and can trace it through the mazes of debate, without losing it.… As a reasoner, he is remarkably perspicuous and methodical. He is a studious man, devoted to public business, and a thorough master of almost every public question that can arise, or he will spare no pains to become so, if he happens to be in want of information. What a man understands clearly, and has viewed in every different point of light, he will explain to the admiration of others, who have not thought of it at all, or but little, and who will pay in praise for the pains he saves them. [Fisher Ames to George Minot, May, 29 1789]

Initially the Senate, under the leadership of Vice President Adams, bogged down in a protracted debate over titles and formalities. Other than the Judiciary Act and the Crimes Act, which were major accomplishment by Senator Oliver Oliver Ellsworth, the lion’s share of the work of the First Congress originated in the House. In virtually every other substantive matter – in particular the adoption of the Bill of Rights – the House took the initiative under Madison’s leadership.

In Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789-1815, historian Gordon Wood recounts that Madison made over one hundred speeches to the House of Representatives in just the first session of the First Congress. “But Madison’s extraordinary dominance over the proceedings of the First Congress came not merely from his reputation and speech-making. His broad knowledge and careful preparation for what had to be done were even more important.” Wood describes, for example, how Madison prepared for the opening debate on revenue by comparing state revenue laws by assembling all available statistical information on commerce between the states.

As described by Bordewich, “From a piece of paper, the members of the First Congress had made a government: the republican dream had been breathed into life, given political flesh and bone, pushed to its fees, and made to walk.”

In the words of John Trumbull, “In no nation, by no Legislature, was ever so much done in so short a period for the establishment of Government, Order, … & general tranquility” (John Trumbull to John Adams, 20 March 1791)

You can purchase a paperback copy of the Acts of the First Congress by clicking on the banner below:

Click here for a discussion of the Proceedings and Debates at the First Congress, published by Joseph Gales

Additional reading and primary sources:

Articles of Confederation and related primary sources (Library of Congress)

Acts of the First Congress (Adams’ copy)

Madison at the First Session of the First Congress (Founders Online)

Center for the Study of the American Constitution

Birth of a Nation: The First Congress (GWU)

Slow Start for the First Congress (Smithsonian Magazine)

Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789-1815 (Wood, 2009)

The Quartet, Orchestrating the Second American Revolution, 1783-1789 (Ellis, 2015)

This is invaluable information. Interesting to know how our government was ultimately shaped. Thank you for sharing such great and thought-provoking facts.