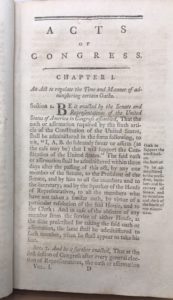

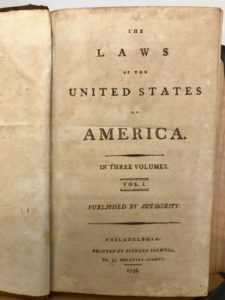

The Oath Act – first act of the First Congress

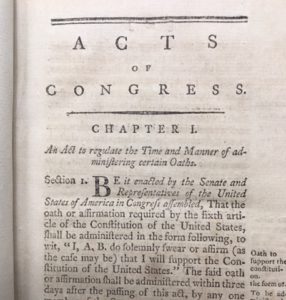

“An act to regulate the time and manner of administering certain oaths”

[1st Congress, Chapter 1; 1 Stat. 23 (1789)]

The first Act of the first Congress was passed on May 5, 1789. Rather than starting with lofty or significant legislation, the first Congress was logical and practical. They decided that the first order of business was the administration of oaths as required by the Constitution. Pictured below are images of New York City, where the First Congress met in Federal Hall beginning in 1789 until the capital was temporarily moved to Philadelphia. Click here for a link to the Residence Act of 1790 which provided for the permanent capital to be built in Washington, D.C.

The first Act of the first Congress was passed on May 5, 1789. Rather than starting with lofty or significant legislation, the first Congress was logical and practical. They decided that the first order of business was the administration of oaths as required by the Constitution. Pictured below are images of New York City, where the First Congress met in Federal Hall beginning in 1789 until the capital was temporarily moved to Philadelphia. Click here for a link to the Residence Act of 1790 which provided for the permanent capital to be built in Washington, D.C.

You can purchase a paperback copy of the Acts of the First Congress by clicking on the banner below:

Meeting for the first time in March of 1789, the first Congress was undertaking an experiment in democracy under our new federal system. Among the important items on their agenda were the establishment of the federal judiciary and cabinet level departments. Ratification of the Constitution had been premised on the adoption of a Bill of Rights. Or, should Congress first create the State Department, Treasury, and War Departments? The first Congress would also need to provide for taxation (the Tariff and Whiskey Acts), establish copyright and patent laws, and create a system of immigration and naturalization. Other small details would include the location of a new capital city, the census, and the creation of federal criminal law. Ultimately, out of the hundreds of proposed acts, 118 bills were enacted into law by the busy first Congress.

Meeting for the first time in March of 1789, the first Congress was undertaking an experiment in democracy under our new federal system. Among the important items on their agenda were the establishment of the federal judiciary and cabinet level departments. Ratification of the Constitution had been premised on the adoption of a Bill of Rights. Or, should Congress first create the State Department, Treasury, and War Departments? The first Congress would also need to provide for taxation (the Tariff and Whiskey Acts), establish copyright and patent laws, and create a system of immigration and naturalization. Other small details would include the location of a new capital city, the census, and the creation of federal criminal law. Ultimately, out of the hundreds of proposed acts, 118 bills were enacted into law by the busy first Congress.

The “Act to Regulate the Time and Manner of Administering Certain Oaths” was signed into law in New York on June 1, 1789 by President Washington. It set forth the simple text of the constitutionally required oath as follows:

“I, A.B. do solemnly swear or affirm (as the case may be) that I will support the Constitution of the United States.”

The Act also established the procedure for administration of the oath, in accordance with Article VI, clause 3 of the Constitution, which merely provided as follows:

The Senators and Representatives before mentioned, and the Members of the several State Legislatures, and all executive and judicial Officers, both of the United States and of the several States, shall be bound by Oath or Affirmation, to support this Constitution; but no religious Test shall ever be required as a Qualification to any Office or public Trust under the United States.”

The adoption of the constitutionally mandated oath implicated an important debate: who should take the oath? Would the same oath apply to both federal officials and state officials? Which state officials? Ultimately, the decision provided an opportunity for Congress to make a firm statement in support of federal supremacy. It was decided that the “same oath” shall be taken by “all members of the Several state legislatures and all executive and judicial officers of the Several States.”

For a link to additional primary sources click here.

The plain 14-word oath was used until the Civil War when Congress strengthened the oath in an effort to exclude disloyal Southerners from office. The so-called “Iron Clad Test Oath” required office holders to swear not only that they would support the Constitution, but that they had been loyal during the war. In 1884, the Iron Clad oath was repealed to allow former Confederates to take the oath in good faith.

Today the oath is codified in U.S. Code, Title 2, Sections § 21, § 22 and § 25 (federal officials), and Title 4, § 101 and § 102 (state level oath).