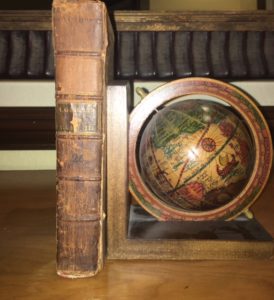

THE STAMP ACT of 1765, Chapter 12, Volume XXVI of Danby Pickering’s Statutes at Large, printed by Joseph Benthem in 1765. [4 GEO III to 5 GEO III]

The Stamp Act of 1765 was the first direct, internal tax levied on the American colonists by England. It was modeled after a similar stamp tax that had been used in Britain for nearly a century. The Act was passed to defray the cost of the successful Seven Years’ War (1756-63), which had been fought in North America.

The Stamp Act of 1765 was the first direct, internal tax levied on the American colonists by England. It was modeled after a similar stamp tax that had been used in Britain for nearly a century. The Act was passed to defray the cost of the successful Seven Years’ War (1756-63), which had been fought in North America.

The Stamp Act imposed a tax on 54 kinds of paper documents (including newspapers, pamphlets, deeds, wills, and licenses). Under the Act nearly everything that could be printed or written was subject to the tax, which required colonists to purchase special stamped paper produced in England. The expensive “stamped” paper was required to be imported from Britain. The broadly applied tax thus applied to newspapers, legal documents, pamphlets, licenses, paper and playing cards. The Act was passed on March 22 and took effect in November of 1765.

By coupling the Stamp Act with the Sugar Act and Currency Act, Prime Minister Grenville was trying to reintroduce a reinvigorated mercantilist policy. Initially, Grenville’s efforts were successful, raising more than ten times as much annual revenue than raised prior to 1763.

The Act required that stamp taxes be paid for with currency. This was problematic for the colonies because hard currencies was scarce. The Act also provided for enforcement in vice-admiralty courts. This was controversial because vice-admiralty courts lacked juries. Taken together these programs were a stark departure from colonial independence and traditions.

It turns out, however, that Grenville could not have devised a better method for antagonizing (and unifying) the colonists had he tried.

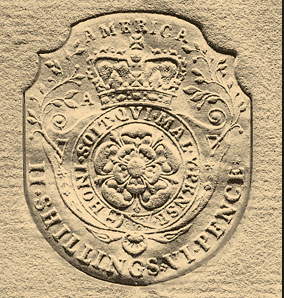

The required stamped paper, depending on the denomination and the paper, contained an image of a Tudor rose alongside the word “America” and the French phrase Honi soit qui mal y pense” (shame to him who thinks evil of it). Ironically, King George was from the House of Hanover, not from the House of Tudor. Nevertheless, the Stamp Act and other miscalculations would ultimately lead to King George’s loss of the American colonies.

The required stamped paper, depending on the denomination and the paper, contained an image of a Tudor rose alongside the word “America” and the French phrase Honi soit qui mal y pense” (shame to him who thinks evil of it). Ironically, King George was from the House of Hanover, not from the House of Tudor. Nevertheless, the Stamp Act and other miscalculations would ultimately lead to King George’s loss of the American colonies.

Other stamp denominations depicted a scepter and sword, with St. Edward’s Crown encircled by the Order of the Garter. You may recognized the image of St. Edward Crown because it has been used since the 13th century at the coronation of British monarchs. It was first used by King Edward the Confessor, who ruled from 1042 to 1066.

In contrast to the Sugar Act which which primarily affected only New England merchants, the Stamp Act impacted almost all Americans, including influential lawyers, printers, tavern owners and shippers. According to historian Arthur M. Schlesinger Sr., the Stamp Act “saddled the burden directly upon the backs of the printers, lawyers, and merchants who (along with the clergy) formed the most literate and articulate section of the Colonial public.” Not surprising this group “formed the most literate and vocal elements of the population” who largely united in opposition to the Stamp Act. In particular, newspaper printers played an important role in communicating information in colonial society. Never before had a colonial tax been so pervasive. As a result, the Stamp Act unified the colonies in their opposition to taxation without representation.

The reaction was almost immediate. Across the colonies like minded protestors began organizing. In particular, the Sons of Liberty, encouraged boycotts and threatened violence against tax collectors. The wide spread opposition to the tax resulted in the shutting down of courthouses because paper was required for legal documents. In October of 1765, delegates from nine colonies assembled in New York at the Stamp Act Congress. Expressing unified colonial resistance, a the Stamp Act Congress declared that the Stamp Act was a violation of the colonial rights and liberties. In 1766, Parliament repealed the Stamp Act, but declared its right to impose similar laws “in all cases whatsoever.” Click here for a link to the Declaratory Act of 1766.