Washington Gambit Hypothesis

the Final Substantive Vote at the Constitutional Convention

Miss Dally Part VII

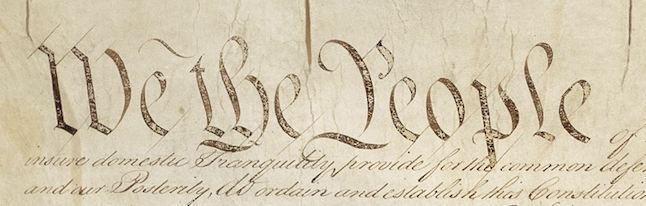

In his role as the President of the Constitutional Convention, George Washington avoided taking part in substantive debates. Yet, on the final day of the Convention George Washington broke his silence. What was the issue that Washington felt compelled to address? The formula for apportioning House districts had been heavily debated for months and was the basis of several compromises at the Convention. Washington’s first presidential veto would involve this controversial topic. The Congressional apportionment formula would also be the subject of the first proposed amendment to the Constitution, which would have become the “First Amendment” had it been adopted.

Surprisingly, on September 17, Washington ventured an opinion in support of a pending motion. Why? Historians agree that Washington’s only speech at the Convention was a significant moment. According to Washington, “his situation [as the presiding officer] had hitherto restrained him from offering his sentiments.” Nevertheless, on this one occasion “he could not forbear expressing his wish” that objections to the draft Constitution “might be made as few as possible.” He therefore supported Nathaniel Gorham’s motion to reduce the size of Congressional districts from 40,000 to 30,000. [1]

Did Washington spontaneously make this unexpected decision to intervene on the floor of the Convention? Or was Washington’s intervention choreographed in advance? While historians generally agree that Washington’s speech on September 17 was “surprising,” they disagree on Washington’s motivation(s).

The “Washington Satisfaction Gambit Hypothesis” theorizes that George Washington’s last-minute intervention to support revising the 40,000:1 House representation formula was specifically orchestrated. The Gambit Hypothesis asserts that Washington broke his silence in a purposeful, but unsuccessful effort to accommodate the three dissenting delegates, Elbridge Gerry, George Mason and Edmund Randolph.

Request for unanimity

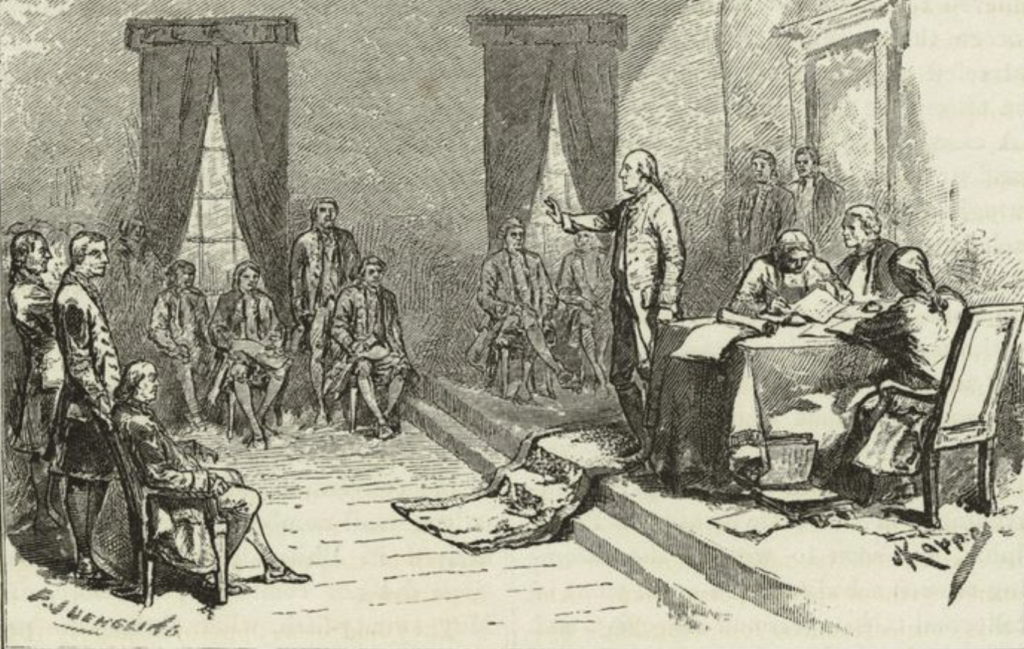

When the delegates entered Independence Hall on the last day of the Constitutional Convention, the beautifully “engrossed” version of the Constitution awaited their signature. The “final” text of the Constitution had been approved on September 15, over the objections of three dissenting delegates (Gerry, Mason and Randolph). [2] During the next two days the Convention’s scribe, Jacob Shallus, painstakingly engrossed the approved text on parchment, which was now ready to be “enrolled” and signed. [3]

According to Madison’s notes, on the morning of September 17 the engrossed Constitution was read one final time. The Convention’s most senior delegate, Ben Franklin, was waiting with a prepared speech. Franklin’s remarks, which were read for him, concluded with “a wish that every member of the Convention who may still have objections to it, would with me, on this occasion doubt a little of his own infallibility, and to make manifest our unanimity, put his name to this instrument.”

Franklin’s effort to win over the three dissenting delegates acknowledged that “there are several parts of this constitution which I do not at present approve, but . . . Sir, I agree to this Constitution with all its faults if they are such; because I think a general Government necessary for us . . . I doubt too whether any other Convention we can obtain may be able to make a better Constitution.”

Consistent with his request for unanimity, Franklin moved that the Constitution be signed by all delegates. To allay concerns by dissenting members, Franklin proposed the following purposely ambiguous phraseology, which he believed “might have a better chance of success”:

Done in Convention by the unanimous consent of the States present the 17th. of Sepr. &c-In Witness whereof we have hereunto subscribed our names.

As recounted by Madison, this “ambiguous form” was “drawn up” by Gouverneur Morris in order to gain the support of the dissenting members and “put into the hands of Doctor Franklin that it might have the better chance of success.” [4] In other words, through the use of semantic sleight of hand, the signers would not all need to personally agree to the Constitution. Rather, they would only affirm that the vote of the state delegations was unanimous.

Gorham’s motion and Washington’s endorsement

Immediately thereafter, prior to the matter being put to a vote, Massachusetts delegate Nathaniel Gorham requested an unexpected amendment. Gorham rose to suggest, “if it was not too late,” that his last-minute motion was intended for purposes of “lessening objections.” Gorham moved to reconsider the formula for apportioning members to the House of Representatives. Indicating that the 40,000 to 1 ratio had produced “much discussion” during the Convention, Gorham moved to “strike out 40,000 and insert 30,000.” According to Gorham, this last-minute motion would not establish “an absolute rule,” but merely give Congress “greater latitude which could not be thought unreasonable.”

After Gorham’s motion was seconded by fellow Massachusetts delegate Rufus King, Washington rose to break his scrupulously maintained silence. Jack Rakove writes that it “must have been wonderous, then, when [Washington] intervened” to support Gorham’s motion. According to Catherine Drinker Bowen, “it must have surprised” the delegates when Washington, “after his summer’s silence, suddenly launched into speech” [5]:

When the PRESIDENT rose, for the purpose of putting the question, he said that although his situation had hitherto restrained him from offering his sentiments on questions depending in the House, and it might be thought, ought now to impose silence on him, yet he could not forbear expressing his wish that the alteration proposed might take place. It was much to be desired that the objections to the plan recommended might be made as few as possible. The smallness of the proportion of Representatives had been considered by many members of the Convention an insufficient security for the rights & interests of the people. He acknowledged that it had always appeared to himself among the exceptionable parts of the plan, and late as the present moment was for admitting amendments, he thought this of so much consequence that it would give much satisfaction to see it adopted

Madison’s notes report that “[t]his was the only occasion on which the President entered at all into the discussions of the Convention.” Following Washington’s remarkable speech, “no opposition was made” to Gorham’s motion which was unanimously adopted without any recorded vote. The number “forty” was erased and “thirty” was inserted in its place in Article I, Section 2. A permanent smudge is visible to this day on the first page of the Constitution.

Thereafter the delegates approved Franklin’s artful motion with “all the States answering ay.” The rest is history. After a handful of additional speeches, the Constitution was signed by all but three delegates, having been “unanimously” approved by the states in attendance.

Conflicting interpretations

Historians universally agree that Washington’s intervention on September 17 was both surprising and significant. Yet, substantially differing explanations are given for why Washington broke his silence and weighed in to support Gorham’s motion.

According to Professor John Boles, when Washington “suddenly” spoke for the first time it was “no doubt to the surprise of all.” Joseph C. Morton writes that Washington “surprised everyone,” when he supported Gorham’s motion, whereupon his “astounded colleagues quickly acquiesced to Washington’s request and passed Gorham’s motion unanimously.” [6]

Joseph Ellis speculates that Washington’s move was a “gesture probably designed to assure that he was on record as a participant as well as a signer.” [7] Richard Beeman suggests that “[t]he only plausible answer is that he knew this would be his last chance to speak on a matter on which his words might elicit unanimity among the delegates.” [8]

Noah Feldman agrees with Ellis and Beeman, but also offers another alternative explanation for why Washington “weighed in” for the first time on the substance of a proposal, “after the deliberations were long completed.” For Feldman, “[p]ossibly he wanted the Convention over; or perhaps he simply wanted to be on the record as having participated.” [9]

Richard Brookhiser notes that the representation formula “was a matter which had been debated, and settled a month earlier.” As summarized by Brookhiser:

Historians debate the motive for Washington’s appeal. Some see it as a sign of his commitment to localism and government by neighborhoods. Others see it in the same light as his vote on the appropriations question – a tactical retreat by a supporter of a smaller, and therefore more vigorous legislature, willing to sacrifice that goal in the interest of harmony. Maybe it is best to see it as a seal of approval. The size of districts was not a major issue. By breaking his silence to endorse a minor change, Washington was signifying to the delegates that no major changes needed to be made. The additional fact that the gesture expressed diffidence toward Gorham and those who had seconded his motion would have made it all the more characteristic of him. [10]

Jack Rakove suggests a more tactical reason for Washington’s appeal, “even though it meant smudging the handsomely engrossed copy of the Constitution the framers were about to sign.” [11] Rakove argues that “Washington may have aimed his appeal this old friend Mason,” who had previously objected to the “structure of the government” which also lacked a bill of rights.

The second defect on Mason’s list of objections to the Constitution indicates that:

In the House of Representatives there is not the substance but the shadow only of representation; which can never produce proper information in the legislature, or inspire confidence in the people; the laws will therefore be generally made by men little concerned in, and unacquainted with their effects and consequences.

As evidence, Rakove observes that Mason appended a note to his objections admitting that his concern “has been in some degree lessened.” [12]

Professor Amar opines that “the irregularity” of Gorham’s eleventh-hour motion “only underscored the importance of the issue.” [13] Based on the unanimous vote, Amar explains that Washington and the framers demonstrated that even before the ratification debate began, they were “sensitive to the structural issue of congressional size.” For W.B. Allen, Washington used his influence in a “conscious effort…to democratize the House of Representatives.” [14] As a result of the motion, the representation formula became twenty-five percent “more generous.”

Glenn A Phelps similarly suggests that Washington’s reason for reducing the minimum size of congressional districts “reveals the pragmatic side” of his thinking. When Washington persuaded “the earlier winning coalition to concede a point they had already obtained” Washington correctly anticipated that the issue of representation would be contested during the ratification. For Phelps, “Washington thought it wise to moderate the apportionment formula in order to focus the ratification debate on issues more advantageous to the federalists.” [15]

As imagined by David O. Stewart, Washington’s involvement was purposely solicited by Hamilton and Madison. Stewart emphasizes Washington’s “immense prestige” which he had preserved by “husbanding it.” Nine days earlier Hugh Williamson had proposed the same amendment that Gorham was now reintroducing. On September 8, the request to lower the representation ratio to 30,000:1 failed by one vote, despite being supported by Hamilton and Madison. Yet on September 17, Washington intervened and applied his influence “in a precise fashion.” According to Stewart, the motion carried unanimously because “Madison and Hamilton had enlisted support from the heaviest artillery in the East Room.” [16] Charles Cerami similarly theorizes that Madison collaborated with Washington. According to Cerami, “[i]t well may be that Madison, with his wish to add power to the people, spoke of this both to Gorham and the General before the subject came up to the floor….” [17]

Whatever Washington’s actual reason(s), Max Farrand writes that Gorham’s motion passed unanimously, “without further discussion,” even though “it had been a matter of serious disagreement before.” [18] According to Clair Keller, the “final substantive action” at the Convention passed unanimously whether the delegates were “weary from four long months of debate over the issue or truly influenced by Washington’s unexpected endorsement.” [19]

Washington Satisfaction Gambit Hypothesis

The “Washington Satisfaction Gambit Hypothesis” argues that George Washington’s last-minute intervention to support Gorham’s motion to reconsider the House representation formula was specifically orchestrated. The Gambit Hypothesis theorizes that Washington’s comments were not spontaneous, but had been choreographed with Alexander Hamilton, Nathaniel Gorham and Rufus King. It is also possible that other members of the Committee on Style were coordinating in the Washington Gambit, including James Madison and Gouverneur Morris.

In his speech, Washington does not hide the reasons why he intervened to offer “his sentiments.” According to Washington, it was his “wish” that the proposed alteration be adopted. “It was much to be desired,” Washington indicated, that “objections” be made “as few as possible.” He further explained that many members of the Convention considered the 40,000:1 ratio “insufficient security for the rights and interests of the people.” Even though the present moment was late for admitting amendments, “he thought this of so much consequence that it would give much satisfaction to see it adopted.” [20]

According to the Washington Gambit Hypothesis, Washington, Gorham and King participated in Hamilton’s stratagem in a final effort to lobby Gerry, Mason and Randolph. Note that Nathaniel Gorham was the immediate past president of Congress. Symbolically, Gorham was also a prominent figure at the Convention as the Chairman of the Committee of the Whole. As described by Max Farrand, “[f]or three whole weeks – from May 30 to June 19 – the important work of the Convention was carried on in a Committee of the Whole House.” [21] Likewise, it was widely understood that George Washington would likely become the incoming president if the Constitution could be successfully ratified.

Thus, the Washington Gambit Hypothesis theorizes that it was no coincidence that Hamilton played the “Washington card.” Nor was it a coincidence that former President Gorham made the motion which served as the justification for future President Washington to break his silence.

It also makes sense that Hamilton would be the member of the Committee on Style to reach out to Washington, as the pair had worked so closely together during the war. As suggested by David O. Stewart and Charles A. Cerami, it may have been Madison who reached out to Washington. Yet another reason why Hamilton may have been the architect of the Washington Gambit is the fact that Hamilton was known for “seizing the initiative politically.” A famous example involves Hamilton’s decision to raise the alarm in July of 1787 that New York Governor George Clinton was prematurely criticizing the Constitution.

As described by John P. Kaminski:

Hamilton’s defense of the Constitution began two months before the Convention concluded. Seizing the initiative politically (as he had done militarily during the war), Hamilton publicly denounced Governor Clinton as an opponent of the Convention. Hamilton would not allow the governor to stay above the fray, waiting for an advantageous moment to take a public stand. Although harshly criticized in the press for alienating the governor, Hamilton rightly anticipated Clinton’s antifederalism and thus probably limited the governor’s effectiveness in opposing the new Constitution. [22]

Accordingly, the Washington Gambit Hypothesis posits that Washington was specifically attempting to accommodate the three dissenting delegates on September 17 by using the potent issue of representation, which had particular potency for the larger states of Virginia and Massachusetts. [23] For example, the Committee on Detail report allocated a total of sixty-five House seats to the First Congress. The three largest states were allocated seats as follows: Virginia (10), Pennsylvania (8), and Massachusetts (8). By definition, larger states stood to gain more seats as the appropriation formula was lowered from 40,000:1 to 30,000:1. The additional “representational” benefit of making the House more “democratic” was an added bonus. Stuart Leibiger refers to the 30,000:1 ratio as a “republican-minded change.” [24]

Indeed, the delegates who made the surprising, last-minute motion to expand the representation formula on September 17 were Gerry’s two colleagues from Massachusetts, Nathaniel Gorham and Rufus King. Less than two weeks earlier, the Convention narrowly rejected Hugh Williamson’s identical motion to expand the apportionment formula. Massachusetts voted “no” on September 8. [25] This time, on the final day of the Convention, Massachusetts switched its vote. Yet, despite Washington’s urging, Gerry, Mason and Randolph still refused to sign the Constitution.

Arguably one of the most important committees at the Convention was the Committee on Style, which was selected by ballot on September 8. Interestingly, Williamson made his motion to revisit the representation formula on September 8, immediately after the Committee on Style was named. [26]

Two of the members of the Committee on Style strongly supported Williamson’s motion on September 8, which would be raised again by Gorham on September 17. Madison seconded Williamson’s September 8th motion to increase representation in the House and Hamilton earnestly spoke in favor of it. According to Madison’s notes, Hamilton “expressed himself with great earnestness and anxiety in favor of the motion.” Hamilton further emphasized that representation in the House should be based on a “broad foundation” not a “so narrow a scale” as to warrant “jealousy in the people for their liberties”:

He avowed himself a friend to a vigorous Government, but would declare at the same time, that he held it essential that the popular branch of it should be on a broad foundation. He was seriously of opinion that the House of Representatives was on so narrow a scale as to be really dangerous, and to warrant a jealousy in the people for their liberties. He remarked that the connection between the President & Senate would tend to perpetuate him, by corrupt influence. It was the more necessary on this account that a numerous representation in the other branch of the Legislature should be established. [27]

The representation formula was also a matter of concern for Elbridge Gerry and George Mason. On July 10 the Third Committee on Representation chaired by Rufus King proposed that the House be initially composed of sixty-five members. Madison moved that the number allowed to each state be doubled. [28] Gerry supported the motion, indicating that he was “for increasing the number beyond sixty-five.” Gerry reasoned that “[t]he larger the number, the less the danger of their being corrupted. The people are accustomed to & fond of a numerous representation, and will consider their rights as better secured by it. The danger of excess in the number may be guarded agst. by fixing a point within which the number shall always be kept.” [29]

Agreeing with Gerry. George Mason likewise spoke in favor of increasing the size of the House. In fact, Mason spoke immediately after Gerry on July 10. According to Mason, too small of a House “would neither bring with them all the necessary information relative to various local interests nor possess the necessary confidence of the people.” [30] As discussed above, the second defect on Mason’s list of objections related to the “shadow only of representation” in the House. While the Washington Gambit failed to sway Mason’s decision to sign the Constitution, Mason conceded that his concern “has been in some degree lessened.” [31]

The issue of representation in Congress was a major topic of debate at the Convention, which required referral to three separate committees of representation. Indeed, Elbridge Gerry was selected as the chair of the first “Committee of Representation” created on July 2. Gouverneur Morris would be the chair of the second “Committee of Representation” created on July 6. Rufus King would chair the final “Committee of Representation” created on July 9. Click here for a chart of all of the committee assignments at the Convention.

Following the Convention, Gerry sent a famous letter dated October 18 to the Massachusetts Legislature explaining his reasons for not signing the Constitution (“Gerry’s objections”). According to Gerry, “My principal objections to the plan, are that there is no adequate provision for a representation of the People—that they have no security for the right of election….” [32] Professor John P. Kaminski believes that Gerry may also have been the author of the famous Anti-Federalist Letters from the Federal Farmer, which date to October of 1787.

In a letter dated October 7, 1787 Mason sent his list of objections to Washington. Mason mentions that “a little Moderation & Temper, in the latter End of the Convention, might have removed.” If the Washington Gambit Hypothesis is correct, Washington specifically attempted to assuage Mason on September 17, but fell short.

One reason why the Washington Gambit may have failed is that the dissenters may have interpreted Washington’s accommodation as part of a larger pressure campaign. For example, Gerry’s final speech on September 17 alluded to Franklin’s remarks, which Gerry viewed as “levelled at himself and the other gentlemen who meant not to sign.” The same, of course, could be said for Washington, Morris and Hamilton’s closing remarks. Or, perhaps the Washington Gambit failed because Gerry, Mason and Randolph’s positions may have been irreconcilable by September 17.

Hamilton-Gerry Nexus Hypothesis

The Washington Satisfaction Gambit Hypothesis does not stand in isolation. It builds on and relates to the “Hamilton-Gerry Nexus Hypothesis.” Click here for a link to the Hamilton-Gerry Nexus Hypothesis which argues that the unexpected cooperation between Hamilton and Gerry on September 10 may have reflected a purposeful effort by Hamilton to accommodate Gerry.

Based on the fact that Hamilton and Gerry had traveled and boarded together, Hamilton would presumably have known of Gerry’s growing dissatisfaction with the Convention. Gerry did not announce his formal objections until September 15 when he presented eight reasons why he had decided not to sign the Constitution.

Both hypotheses (Washington Gambit and Hamilton-Gerry Nexus) theorize that Hamilton may have played an underappreciated role in the final week of the Convention. The fact that Hamilton was boarding with Elbridge Gerry at Miss Dally’s is central to this reasoning. Moreover, Hamilton and his fellow delegates on the Committee of Style (Morris, Madison and King) certainly played leading roles on September 17 in the effort to reconcile the three dissenting delegates:

- Morris formulated Franklin’s artful motion that signatories would only be confirming the unanimous vote by the state delegations, not individual delegates. Morris also offered one of the last concluding remarks in favor of the Constitution, which was “the best that was to be attained.”

- Hamilton’s concluding remarks “expressed his anxiety that every member should sign” as a handful of delegates of consequence might do “infinite mischief by kindling” latent sparks of opposition. By pointing out that “no man’s ideas were more remote” from the final draft than his, Hamilton sided with the “chance of good to be expected” rather than the risk of anarchy and convulsion.

- King seconded Gorham’s motion to revisit that 40,000:1 representation formula and likely changed his vote from September 8. King may also have coordinated with Hamilton, Gorham and Madison to convince Washington to break his silence.

If both hypotheses are correct, the Constitution’s Cover Letter [33] may also have been part of a larger effort to accommodate Gerry, Mason and Randolph. If so, the Constitution’s Cover Letter had several audiences and purposes: 1) to convince Congress to send the Constitution to the states for ratification; 2) to convince the state legislatures to call for ratification conventions; 3) to convince the electorate to vote for Federalist candidates who would approve the Constitution; 4) to convince the state ratification conventions to ratify; 5) to justify the Convention’s legal violations (of the Articles of Confederation’s amendment procedures and delegate instructions); and 6) to help convince Gerry, Mason and Randolph to sign the Constitution on September 17.

This post will continue with a discussion of the First Presidential Veto and the “First” Amendment (pending), which both involved the controversial representation formula for the House.

Sources

[1] Max Farrand, 2 The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787 at 644.

[2] 2 Farrand at 633.

[3] John C. Fitzpatrick, “The Man Who Engrossed the Constitution” in History of the Formation of the Union Under the Constitution (Washington, 1941) at 761-769.

[4] 2 Farrand at 641-649.

[5] Jack N. Rakove, Original Meanings: Politics and Ideas in the Making of the Constitution, (Vintage Books, 1996) at 228; Catherine Drinker Bowen, Miracle at Philadelphia: The Story of the Constitutional Convention (Little Brown, 1966) at 257.

[6] John B. Boles, 7 Virginians: The Men Who Shaped Our Republic (Univ. of Virginia Press, 2023); Joseph C. Morton, Shapers of the Great Debate at the Constitutional Convention of 1787 (Greenwood Press, 2006) at 291.

[7] Joseph Ellis, His Excellency: George Washington (Alfred A. Knopf, 2004) at 178.

[8] Richard Beeman, Plain Honest Men: The Making of the American Constitution (Random House, 2009) at 361.

[9] Noah Feldman, The Three Lives of James Madison: Genius, Partisan, President (Random House, 2017) at 169.

[10] Richard Brookhiser, Rediscovering George Washington: Founding Father (Simon & Schuster, 1996) at 68.

[11] Jack N. Rakove, Original Meanings: Politics and Ideas in the Making of the Constitution, (Vintage Books, 1996) at 228.

[12] Rakove, Original Meanings at 228; Mason’s Objections, 2 Farrand at 637.

[13] Akhil Reed Amar, The Bill of Rights: Creation and Reconstruction (Yale Univ. Press, 1998) at 13.

[14] W. B. Allen, The Federalist Papers: A Commentary (Peter Lang) at 307.

[15] Glenn A. Phelps, George Washington and American Constitutionalism (Univ. Press of Kansas, 1993) at 101.

[16] David O. Stewart, The Summer of 1787: The Men Who Invented the Constitution (Simon & Schuster, 2007) at 240.

[17] Charles A. Cerami, Young Patriots: The Remarkable Story of Two Men, Their Impossible Plan and the Revolution that Created the Constitution (Sourcebooks, 2005) at 179.

[18] Max Farrand, “George Washington in the Federal Convention,” Yale Review, 1907 at 286.

[19] Clair W. Keller, The Failure to Provide a Constitutional Guarantee on Representation, 13 Journal of the Early Republic 23 (Spring, 1993).

[20] 2 Farrand at 644.

[21] Max Farrand, George Washington in the Federal Convention, 16 The Yale Review 282 (1907).

[22] John P. Kaminski, Alexander Hamilton: From Obscurity to Greatness (Wisconsin Historical Press, 2016) at xvii; see also John P. Kaminski, George Clinton: Yeoman Politician of the New Republic (Madison House Publishers, 1993) at 123.

[23] 2 Farrand at 130.

[24] Stuart Leibiger, Founding Friendship: George Washington, James Madison, and the Creation of the American Republic (Univ. Press of Virginia, 1999) at 78.

[25] 2 Farrand at 554. (Sept 8)

[26] 2 Farrand at 553.

[27] 2 Farrand at 553.

[28] 1 Farrand at 568. (July 10)

[29] 1 Farrand at 569.

[30] Id.

[31] 2 Farrand at 638.

[32] 3 Farrand at 128. By way of example, Federal Farmer No. 2 discusses the importance of “a full and equal representation” of the people. Gerry’s October 18 letter to the Massachusetts Legislature lists the lack of an “adequate provision for a representation of the People…” The first Federal Farmer essay was dated October 8, 1787. While these Anti-Federalist essays are commonly attributed to Richard Henry Lee or Melancton Smith, their authorship has been debated for decades.

[33] 2 Farrand at 666.