THE NEW YORK ANTI-FEDERALIST PLAN TO SABOTAGE ALEXANDER HAMILTON AT THE CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION

On March 6, 1787, the New York Legislature appointed three delegates to attend the Constitutional Convention. While the decision by New York to attend the Philadelphia Convention was a positive step, its delegates arrived with competing agendas. Alexander Hamilton was a well known nationalist who had been advocating for a stronger central government for years. Yet, his two co-delegates, Robert Yates and John Lansing, were specifically chosen by the New York Legislature to protect the status quo and shackle Hamilton.

This post tells the story of the behind the scenes struggle in the New York delegation at the Constitutional Convention. As discussed below, Governor Clinton and his anti-reform allies sought to limit Hamilton’s influence. Because Hamilton was only one of three delegates from New York, he was consistently outvoted on every issue by his delegation. Nevertheless, Hamilton served on two critically important committees during the first and last months of the Convention and would help advance the nationalist cause.

John Church Hamilton (Hamilton’s son) would later describe the irony when writing his father’s biography. New York would send to the Constitutional Convention the “most prominent advocate” for the union – Alexander Hamilton – who would be opposed at every step by the union’s “most prominent” adversaries (Robert Yates and John Lansing who were following the marching orders of New York Governor Clinton).

Fully recognizing the resistance that the Constitution would face in New York, Hamilton preemptively initiated the ratification campaign in July, before the Convention concluded in September. While all other state delegations in attendance approved the Constitution, Hamilton would be the only delegate from New York to sign the Constitution, in his unofficial, individual capacity.

Historian Joseph Ellis in the book The Quartet, describes Hamilton as one of the four leaders most responsible for the “Second American Revolution” of 1787, which resulted in the U.S. Constitution. According to Ellis, Hamilton recognized, diagnosed and cured the problems of the Articles of Confederation working together with the “Fantastic 4” of Washington, Madison and Jay. For Ellis this result was arguably “the most creative and consequential act of political leadership in American history.”

Hamilton’s Continentalist agenda in the early 1780s

Alexander Hamilton served in the Confederation Congress from 1782 to 1783. He had witnessed first-hand the inadequacy of the Articles of Confederation during the Revolutionary War. As early as 1780, while serving as aide de camp to Washington, Hamilton began floating proposals to fix the Articles of Confederation. Writing as The Continentalist in 1781 Hamilton authored a series of forward-looking essays describing “the want of power in Congress” and calling for a stronger central government. Hamilton also wrote to political leaders outlining specific financial plans that would require a more robust federal government. In particular, his April 30, 1781 letter to Robert Morris was years ahead of its time.

After the Revolutionary War, the nation was not yet ready to embrace Hamilton’s proposed reforms. Yet, within only a few years, it would become clear that the nation was beginning to disintegrate as the country suffered through a post-war depression. As the nation’s currency became increasingly worthless, Congress was unable to solve a mounting debt crisis. The prospect of domestic unrest further illustrated the defects in the Articles of Confederation. On the international front, Britain had refused to withdraw its forces from forts in the Northwest and Spain was perpetually restricting navigation on the Mississippi.

Rather than unifying, the newly independent states began treating each other as adversaries. For example, Virginia and Maryland disputed over navigation rights on their shared rivers. While America had won the war it was unclear if it could win the peace. With the outbreak of violence in Western Massachusetts during Shays’ Rebellion in 1786, the risks of inaction became increasingly clear.

The Audacity of the Annapolis Convention

Realizing that action was needed to remedy the defects with the Articles of Confederation, Virginia called for a meeting of all thirteen states in September of 1786 in Annapolis, Maryland. Only five states sent delegations. And of the states that attended, most of the delegations were only charged with discussing the narrow issue of trade among the states.

Fortunately Alexander Hamilton and James Madison were two of the “commissioners” appointed to the Annapolis Convention. Abandoning their stated objective of proposing commercial powers to strengthen the Confederation Congress, the Annapolis commissioners recommended a general convention of states to meet in Philadelphia in May of 1787. The September 14, 1786 Resolution of the Annapolis Convention was drafted by Alexander Hamilton.

The resulting September 16 Annapolis Resolution explained that the “situation of the United States” was “delicate and critical, calling for an exertion of the united virtue and wisdom of all the members of the Confederacy.” Accordingly, reforms were necessary “to render the constitution of the federal government adequate to the exigencies of the Union.” Of course, Hamilton had been floating similar proposals dating back to 1780. For Hamilton, the nation had learned the wrong lessons from the American Revolution. Fear of political power was resulting in anarchy. The fact that only five states attended was par for the course.

Rather than accepting defeat, historian Joseph Ellis describes Hamilton’s “out-front leadership in its most flamboyant form” at the Annapolis Convention. “A convention called to address the modest matter of commercial reform had just failed to attract even a quorum, and now Hamilton was using the occasion to announce the date for another convention that would tackle all the problems affecting the confederation at once.” For Ellis this moment was s “a display of almost preposterous audacity” by Hamilton.

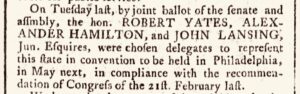

Appointment of the New York Delegation on March 6, 1787

The following year twelve states appointed delegates to meet in Philadelphia. As depicted above in March of 1787 (and as reprinted in newspapers around the country), the New York Assembly selected three delegates to represent the state “in convention to be held in Philadelphia, in May next…”

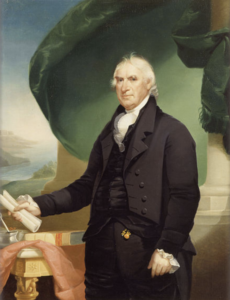

According to Professor John Kaminski, the longtime editor of the Documentary History of the Ratification of the Constitution, Hamilton was well known as a “staunch supporter of strengthening Congress.” For this reason, the New York Assembly “shackled” Hamilton with Robert Yates and John Lansing (devoted Clintonians) who were both averse to transferring more power to Congress. New York’s powerful Governor, George Clinton, was in his tenth year in office and was an early Anti-Federalist. Pictured below, Clinton would eventually serve as Governor for over twenty years before being elected the fourth Vice President under Presidents Jefferson and Madison.

At the Constitutional Convention states voted by delegation. Lansing and Yates, who were related by marriage, effectively controlled the New York delegation. Hamilton would thus be repeatedly outvoted by Yates and Lansing, on every issue.

Ron Chernow observes that rather than leading a united delegation, “Hamilton was demoted to being a minority delegate from a dissenting state.” According to Chernow, the “chief catalyst for the convention” would be hamstrung by a hostile Governor and his anti-reform surrogates.

In fact, in the months leading up to the Convention, Madison had assessed the state delegations that were being assembled. In a March 18, 1787 letter to Washington Madison accurately described Hamilton’s conundrum:

The deputation of N. York consists of Col. Hamilton, Judge Yates and a Mr Lansing. The two last are said to be pretty much linked to the antifederal party here, and are likely of course to be a clog on their colleague.

Madison was only half correct. Yates and Lansing did their best to undermine the effort to replace the Articles of Confederation, but this forced Hamilton to think strategically about the ratification process before the Convention even began in May.

Hamilton at the Philadelphia Convention

On June 16, 1787 New York delegate John Lansing addressed the Convention and expressed his opposition to the Virginia Plan. Lansing declared that the delegates should adhere to their instructions which were to “alter and amend” the Articles, not form a new “national government.”

Hamilton responded with a five hour speech on June 18, which included an 11 point plan. He began his all day oration by explaining that he had remained silent thus far out of “respect for others” with “superior abilities, age and experience.” Hamilton also acknowledged his “delicate situation with respect to his own state.” Of course, Hamilton’s “delicate situation” was Yates and Lansing.

As described by Connecticut delegate William Samuel Johnson, “the gentleman from New York is praised by every gentlemen,” but supported by no gentleman. Nevertheless, Hamilton’s plan was a bookend on the right of the Virginia Plan, which helped advance the great compromises in Philadelphia. The net result is what some have described as the Miracle in Philadelphia.

Hamilton left the Convention in early July. After Yates and Lansing left in mid July, Hamilton returned to actively participate in debates, but was unable to vote since the New York delegation lacked a required quorum of two members.

While delegates from other states would also leave the Convention for various reasons, Yates and Lansing were the first to leave based on their disagreement with the Great Compromise. Also known as the Connecticut Compromise, this decision would consolidate federal power and replace the hapless Confederation Congress with a powerful bicameral Congress consisting of a House and Senate.

Hamilton was not deterred, however, by his inability to vote under the Convention rules after Yates and Lansing returned to New York. During the Convention Hamilton served on the Convention’s first committee (the Rules Committee) as well as the Convention’s final committee (the Committee on Style and Arrangement). This last committee of five members produced the Preamble, the final draft of the constitution, the resolution describing the ratification procedure, and the Constitution’s Cover Letter. And perhaps most importantly, Hamilton played a central role in the ratification process because he knew full well what he was up against in New York.

Opening shots in the New York Ratification battle

As described by Professor Kaminski, Hamilton’s defense of the Constitution began two months before the Convention ended. “Seizing the initiative politically (as he had done during the war), Hamilton publicly denounced Governor Clinton as an opponent of the Convention”:

Hamilton would not allow the governor to stay above the fray, waiting for an advantageous moment to take a public stand. Although harshly criticized in the press for alienating the governor, Hamilton rightly anticipated Clinton’s antifederalism and thus probably limited the governor’s effectiveness in opposing the new Constitution.

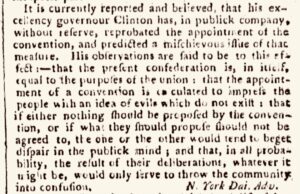

In a letter dated July 21, 1787 in the New York Daily Advertiser Hamilton took the offensive charging that Governor Clinton “has, in public company, without reserve, reprobated the appointment of the Convention, and predicted a mischievous issue of that measure.” Hamilton then listed Governor Clinton’s objections, and in Hamiltonian fashion, systematically refuted them.

Copied above is an excerpt from Hamilton’s July 21, 1787 letter. It is noteworthy that Hamilton’s shot across the bow to Clinton was written two months before the Convention finished its work on September 17, 1787. Hamilton would begin writing the Federalist Papers shortly thereafter.

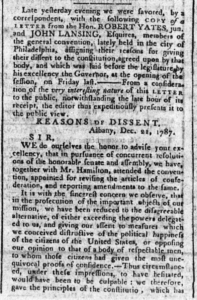

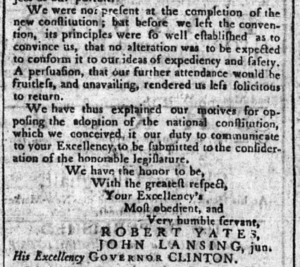

For their part, Yates and Lansing did not quietly sit back after they left Philadelphia. In December of 1788 they explained in a widely published letter to Governor Clinton the reasons for their opposition to the Constitution. Copied below is Yates’ and Lansing’s explanation for their early departure from the Convention. Governor Clinton presented the widely reprinted letter to the New York Legislature at the same time that he presented the report of the Philadelphia Convention.

Not surprisingly, during the New York ratification convention Lansing was a vocal Anti-Federalist opponent of the Constitution. Yates may have written a series of letters as Brutus attacking the Constitution. Yates also published his less than favorable (and incomplete) notes about the Philadelphia Convention in 1821 under the title Secret Proceedings and Debates of the Convention Assembled…for the Purpose of Forming the Constitution of the United States.

The rest is history. After the Constitution was ratified, Yates and Lansing would go on to serve as Justices of the New York Supreme Court. Interestingly, many years later Lansing would preside over the famous murder trial of Levi Weeks in 1800. Notwithstanding their rivalry years earlier, Lansing ruled for the defense led by Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr.

Additional reading:

Alexander Hamilton: From Obscurity to Greatness, John Kaminski (2016)

The Quartet: Orchestrating the Second American Revolution, Joseph Ellis (2015)

Alexander Hamilton, Ron Chernow (2004)

Alexander Hamilton: A Biography, Forrest McDonald (1979)

The Life of Alexander Hamilton, John Church Hamilton (1840)

Here is a video produced by Sergio Villavicencio of the Alexander Hamilton Awareness Society commemorating the appointment of Hamilton, Yates and Lansing to the New York delegation on March 6, 1787.