The Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871 (the Civil Rights Act of 1871)

17. Stat. 13; Forty-Second Congress, Session 1, Ch. 22]

Officially titled “An Act to enforce the Provisions of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, and for other purposes,” the Civil Rights Act of 1871 is also known as the Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871, the Enforcement Act of 1871, and the Force Act of 1871 (hereinafter cited as “the 1871 Act”). Despite the law’s checkered history, several provisions of the 1871 Act have become vital tools for enforcing civil rights in modern times.

While the 1871 Act was successfully used by President Grant to suppress the KKK during Reconstruction, the controversial law fell into disuse beginning in the 1880s. After being narrowly interpreted by the courts for nearly a hundred years, the 1871 Act found new life beginning in the 1960s when the Supreme Court began allowing Section 1983’s “under color of law” provision to be used to hold state and local officials responsible for civil rights violations.

This post is divided into three parts. Part I discusses the legislative history behind the 1871 Act, which was specifically requested by President Grant to combat the Ku Klux Klan in the South. Part II explores the text of the Act, which was reorganized and dispersed within the Revised Statutes in 1874. Part III discusses the more well known provisions of the Act which can be found in Sections 1983 and 1985 of Title 42 of the United States Code.

Part I: Legislative history of the KKK Act of 1871 (Reconstruction, the Civil Rights Act of 1866 and Grant’s recognition of the need to combat the KKK)

Following the Civil War, Congress passed several civil rights laws during Reconstruction in an effort to protect the rights of newly freed slaves. When the Southern states began to impose “Black Codes” to subjugate former slaves, it became clear that the adoption of the 13th Amendment which outlawed slavery was inadequate.

The Civil Rights Act of 1866 was the first civil rights law in American history. It was adopted over the veto of President Andrew Johnson. Due to doubts over the constitutionality of the Civil Rights Act of 1866, Congress adopted the 14th Amendment, which was ratified in 1868.

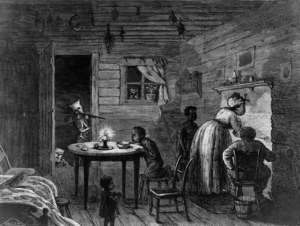

Understanding the brutality of the Ku Klux Klan, President Grant requested that Congress grant him the authority that he believed he needed to intervene in the South. Republican governor Robert K. Scott of South Carolina had written to Grant seeking federal assistance. As described by Scott, “Colored men and women have been dragged from their homes at the dead hour of night and most cruelly and brutally scourged for the sole reason that they dared to exercise their own opinions upon political subjects.”

President Grant responded by writing to House Speaker James Blaine on March 9, 1871 that, “[t[here is a deplorable state of affairs existing in some portions of the South demanding the immediate attention of Congress.” Grant asked Congress to devote its next session “to the single subject of providing means for the protection of life and property” in the areas of the South being brutalized by the Klan.

Two weeks later, on March 23, 1871, Grant formally requested legislative action in a special message to Congress:

A condition of affairs now exits in some of the States of the Union renewing life and property insecure, and the carrying of the mails, and the collection of revenues dangerous. The proof that such a condition of affairs exists in some localities is now before the Senate. That the power of the Executive of the United States, acting within the limits of existing laws, is sufficient for present emergencies is not clear. Therefore, I urgently recommend such legislation, as in the judgment of Congress, shall effectively secure the life, liberty and property, and the enforcement of law in all parts of the United States.

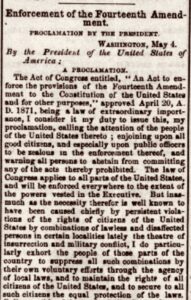

After the 1871 Act was adopted to enforce the 14th Amendment, Grant issued a special proclamation on May 3, 1871 warning that KKK violence would not be tolerated.

The act of Congress entitled “An act to enforce the provisions of the fourteenth amendment to the Constitution of the United States, and for other purposes,” approved April 20, A. D. 1871, being a law of extraordinary public importance, I consider it my duty to issue this my proclamation, calling the attention of the people of the United States thereto, enjoining upon all good citizens, and especially upon all public officers, to be zealous in the enforcement thereof, and warning all persons to abstain from committing any of the acts thereby prohibited.

Grant forcefully described that the law “will be enforced everywhere to the extent of the powers vested in the Executive.” Grant tried to peacefully appeal to Southerners to voluntarily comply:

“. . . inasmuch as the necessity therefor is well known to have been caused chiefly by persistent violations of the rights of citizens of the United States by combinations of lawless and disaffected persons in certain localities lately the theater of insurrection and military conflict, I do particularly exhort the people of those parts of the country to suppress all such combinations by their own voluntary efforts through the agency of local laws and to maintain the rights of all citizens of the United States and to secure to all such citizens the equal protection of the laws.

“Fully sensible” of his responsibilities and “extraordinary powers” conferred on him by the new law, President Grant warned that “I will not hesitate to exhaust the powers thus vested in the Executive, whenever and wherever it shall become necessary to do so for the purpose of securing to all citizens of the United States the peaceful enjoyment of the rights guaranteed to them by the Constitution and laws.”

Copied below is a copy of Grant’s proclamation, which was published in newspapers around the country.

As described by historian Ron Chernow, “Klan violence was unquestionably the worst outbreak of domestic terrorism in American history, and Grant dealt with it aggressively, using all the instruments at his disposal.” “In pursuing the Klan, he showed to advantage his persistence, simplicity, and innate stubbornness.”

Among other things, the 1871 Act authorized Grant to use the military to stop “insurrection, domestic violence, unlawful combinations, or conspiracies” against civil rights if a state’s government failed to act. Consistent with Lincoln’s suspension of habeas corpus during the Civil War, the Act similarly allowed Grant to suspend habeas corpus for up to a year.

Knowing the limitations of military power, Grant decided to make an example of the piedmont region of South Carolina, where some of the worst Klan violence had taken place. In York County, South Carolina, Attorney General Amos Akerman and Army Major Lewis Merrill found evidence of eleven murders and more than 600 whippings and related assaults. Based on his investigation, Akerman described how regions of rural South Carolina were “under the domination of systematic and organized depravity.” Major Merrill claimed that the situation was a “carnival of crime not paralleled in the history of any civilized community.”

After the Klan failed to comply with Grant’s warning and local grand juries failed to take action, Grant suspended habeas corpus and declared martial law in nine South Carolina counties. Grant sent in the 7th U.S. Cavalry and U.S. Marshals to round up suspected Klan members for trial. The newly created Justice Department, supervised by Attorney General Akerman, oversaw the prosecution of the KKK.

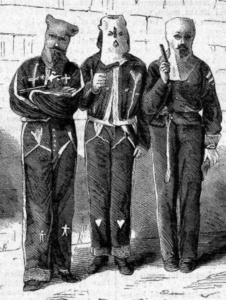

President Grant had signed into law the Act to Establish the Department of Justice on June 22, 1870 (ch. 150, 16 Stat. 162). Grant ordered that the Justice Department’s initial mandate was to counter those groups who used intimidation and violence in the South. In Grant’s first year in office, over 1,000 members of the KKK were indicted (with 550+ convictions). By late 1871, more than 3,000 indictments were issued against the KKK, which was largely defeated by Grant and Attorney General Akerman, until the KKK reemerged in the 1900s. Copied below is an illustration of three KKK members arrested in Mississippi in 1871.

Part II: Provisions of the 1871 Act

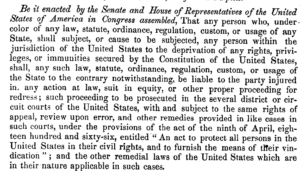

Section 1 of the 1871 Act provided that any person who, “under color of any law,” deprived another of any right, privileges, or immunities secured by the Constitution was liable in federal court for damages. This now famous provision created a civil remedy for violations of individual rights, which is now codified in 42 U.S.C. §1983.

Section 1 allowed former slaves (or other plaintiffs) to sue state and local officials for violating federal law. Importantly, Section 1 enabled private citizens to use the federal courts to enforce their rights. In addition to damages, injunctive relief was available to bar future violations.

Section 2 established criminal sanctions as well as liability for civil damages for conspiracies by two or more individuals acting against the government of the United States. Codified today in 42 U.S.C. §1985, Section 2 also provided for liability for those conspiring to oppose “by force, intimidation, or threat to prevent, hinder, or delay the execution of any law of the United States…”

Section 2 is the basis of lawsuits that have been brought against President Trump arising out of the election of 2020 and the January 6, 2021 assault on the U.S. Capitol. Click here for a link to Congressman Bennie Thompson’s lawsuit brought by the NAACP alleging violations of Section 1985 (which applies to conspiracies “to prevent, by force, intimidation, or threat any person … holding any office, trust, or place of confidence under the United States … from discharging any duties thereof; or to induce by like means any officer of the United States to leave any … place[] where his duties as an officer are required to be performed, or … to molest, interrupt, hinder, or impede him in the discharge of his official duties”).

Section 3 authorized the President to use the armed forces to put down rebellions. Section 4 permitted the President to suspend the writ of habeas corpus for a period not exceeding one year. Section 5 provided for jurors to swear that they did not have any allegiances to groups such as the KKK. Section 6 provided that individuals with knowledge of a conspiracy who failed to take reasonable action to prevent wrongful acts could also be held liable for deaths resulting from the failure to act. A copy of the entire 1871 Act can be viewed here. Copied below is an illustration from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper of President Grant signing the Act into law in the President’s room at the Capitol with Secretary of the Navy Robeson and General Horace Porter on April 20, 1871.

Part III: Modern codification of the 1871 Act in Title 42 of the US Code

Although the 1871 Act was successfully used by President Grant to strike serious blows against the Klan, the law was substantially weakened by the United States Supreme Court within a decade. Beginning with the Slaughterhouse Cases (1873), the Supreme Court applied a narrow interpretation of the privileges and immunities clause of the 14th Amendment. In the case of U.S. v. Harris (1882) the Supreme Court struck down the criminal conspiracy provisions of the 1871 Act. The Court held that the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection clause only applied to state action, not state inaction.

Nevertheless, President Eisenhower invoked the 1871 Act in 1957. After Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus used the Arkansas National Guard to block school desecration at Central High School, Eisenhower relied on the obscure provisions of the 1871 Act to order federal troops to Little Rock.

Importantly, in 1961 the Supreme Court breathed new life into Section 1983 when it began interpreting the phrase “under color of law” to apply when state and local officials were knowingly violating civil rights. In Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167 (1961) the Court held that Congress “meant to give a remedy to parties deprived of constitutional rights, privileges, and immunities by an official’s abuse of his position” under section 1983.

Copied below is a discussion of the important civil rights protections which are codified today in Title 42 of the United States Code.

42 U.S.C. §1981 (Civil Rights Act of 1866)

Section 1981 contains a generic promise of civil rights to all persons within the United States. The law was originally adopted as part of the Civil Rights Act of 1866. Section 1981 grants all persons within the United States the same right “as is enjoyed by white citizens” to make and enforce contracts, to sue and to be subject to identical punishments, taxes, and other treatment by the government.

All persons within the jurisdiction of the United States shall have the same right in every State and Territory to make and enforce contracts, to sue, be parties, give evidence, and to the full and equal benefit of all laws and proceedings for the security of persons and property as is enjoyed by white citizens, and shall be subject to like punishment, pains, penalties, taxes, licenses, and exactions of every kind, and to no other.

42 U.S.C. §1982 (property rights and the Civil Rights Act of 1866)

Section 1982 grants all U.S. citizens the same property rights as whites, including the right to inherit, purchase and sell land and other personal property. Both 42 U.S.C. sections 1981 and 1982 were originally adopted as part of the Civil Rights Act of 1866. Section 1982 provides as follows:

All citizens of the United States shall have the same right, in every State and Territory, as is enjoyed by white citizens thereof to inherit, purchase, lease, sell, hold, and convey real and personal property.

42 U.S.C. §1983 (deprivations “under color of law” and the Civil Rights Act of 1871)

Section 1983 is one of the best known federal statutes and is commonly used in suits against state and local government officials for civil rights violations. It was originally adopted as part of the Civil Rights Act of 1871. Section 1983 allows private suits for damages against any person who “under color of any statue” or other law deprives an individual of “any rights, privileges or immunities secured by the Constitution and laws.” While Section 1981 was premised on the Thirteenth Amendment, Section 1983 and the 1871 Act seek to enforce the 14th Amendment. Section 1983 provides as follows:

Every person who, under color of any statute, ordinance, regulation, custom, or usage, of any State or Territory or the District of Columbia, subjects, or causes to be subjected, any citizen of the United States or other person within the jurisdiction thereof to the deprivation of any rights, privileges, or immunities secured by the Constitution and laws, shall be liable to the party injured in an action at law, suit in equity, or other proper proceeding for redress, except that in any action brought against a judicial officer for an act or omission taken in such officer’s judicial capacity, injunctive relief shall not be granted unless a declaratory decree was violated or declaratory relief was unavailable. For the purposes of this section, any Act of Congress applicable exclusively to the District of Columbia shall be considered to be a statute of the District of Columbia.

Section 18 U.S.C. 242 contains the criminal analog to Section 1983. Thus, fines and imprisonment may be imposed against any person who “under color of any law…” willfully deprives another of any rights protects by the Constitution or federal laws, on account of color, race or alienage. A term of life imprisonment is authorized if the deprivation results in death.

42 U.S.C §1985 (private conspiracies to deprive of equal protection or privileges and immunities under the law and the Civil Rights Act of 1871)

When two or more persons conspire to deprive another of equal protection of the law they may be sued under 48 U.S.C. §1985(3). Even if there is no “state action”, suit may be brought under section 1985 as long as a federally guaranteed right was infringed. Section 1983 and 1985 are derived from the Civil Rights Act of 1871. Section 1985 provides in material part:

If two or more persons in any State or Territory conspire or go in disguise on the highway or on the premises of another, for the purpose of depriving, either directly or indirectly, any person or class of persons of the equal protection of the laws, or of equal privileges and immunities under the laws; or for the purpose of preventing or hindering the constituted authorities of any State or Territory from giving or securing to all persons within such State or Territory the equal protection of the laws; or if two or more persons conspire to prevent by force, intimidation, or threat, any citizen who is lawfully entitled to vote, from giving his support or advocacy in a legal manner, toward or in favor of the election of any lawfully qualified person as an elector for President or Vice President, or as a Member of Congress of the United States; or to injure any citizen in person or property on account of such support or advocacy; in any case of conspiracy set forth in this section, if one or more persons engaged therein do, or cause to be done, any act in furtherance of the object of such conspiracy, whereby another is injured in his person or property, or deprived of having and exercising any right or privilege of a citizen of the United States, the party so injured or deprived may have an action for the recovery of damages occasioned by such injury or deprivation, against any one or more of the conspirators.

Section 18 U.S.C. 241 in turn criminalizes conspiracies that “injure, oppress, threaten, or intimidate any citizen in the free exercise or enjoyment of any rights or privilege” secured under the Constitution or the laws of the United States.

Additional Reading:

President Grant Takes on the Ku Klux Klan