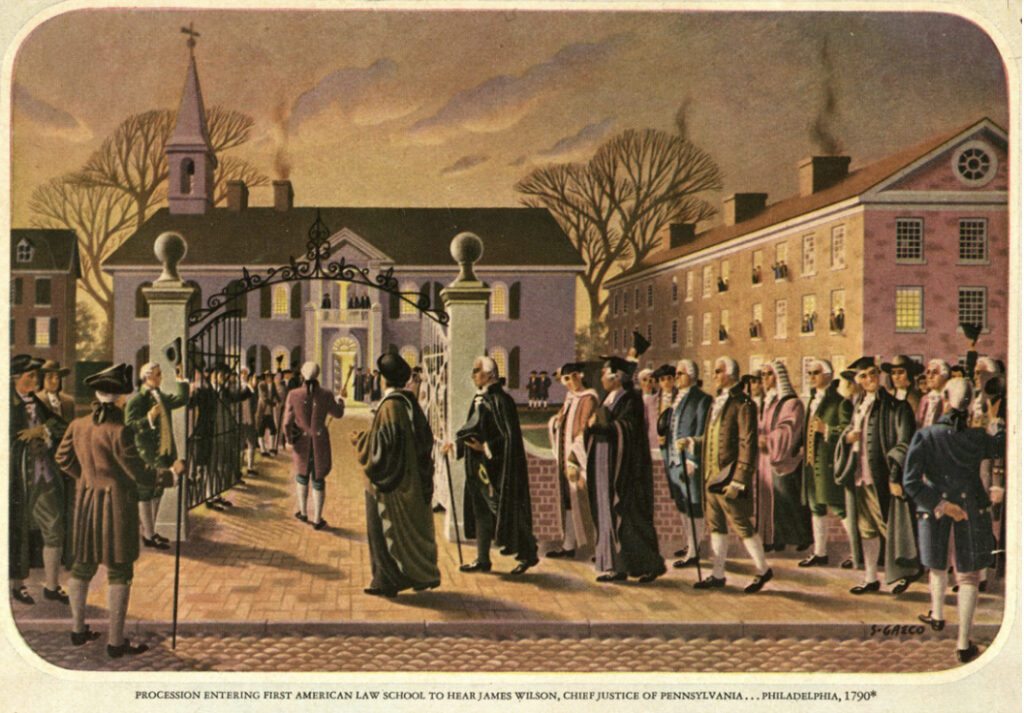

James Wilson’s introductory law lecture to President Washington, Congress and other esteemed guests

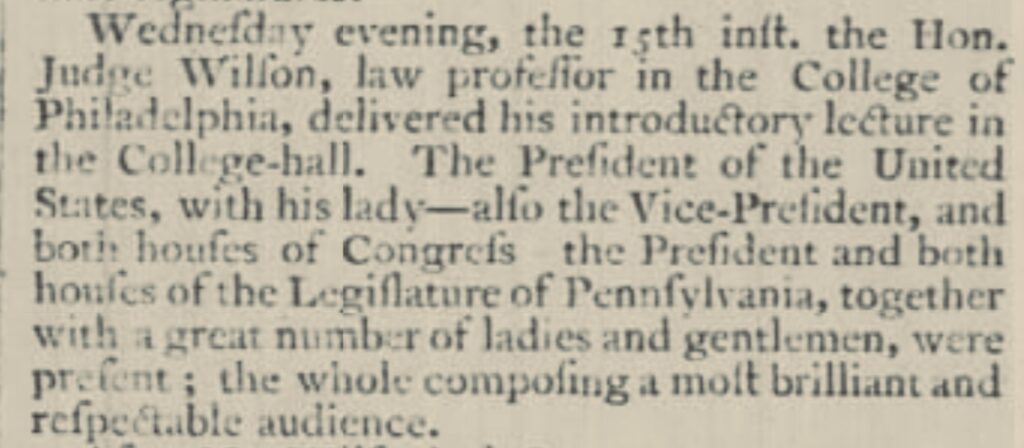

At 6:00 p.m. on Wednesday, December 15, 1790, founding father, professor and Supreme Court Justice James Wilson presented an introductory lecture to President Washington, Vice President Adams, and Congress. Also in attendance were Martha Washington, the Governor and Legislature of Pennsylvania, and “a great number of ladies and gentlemen…composing a most brilliant and respectable audience.” What would eventually become a series of 58 lectures by Professor Wilson at one of the nation’s first law schools would be cited 230 years later at the Senate trial of President Donald Trump.

The extraordinary crowd was assembled for Wilson’s inaugural law lecture as the first Professor of Law at the College of Philadelphia. Earlier that month, the federal government had arrived in Philadelphia, its temporary home, after relocating from New York, the nation’s first capital. According to the recently adopted Residence Act, all federal offices “attached to the seat of government” would relocate to and remain in Philadelphia for the next ten years while the new capital was constructed along the Potomac.

Today, modern audiences may find it hard to believe that the entire political establishment of the the federal government and the nation’s largest state would socialize in this fashion after hours. Yet, as described by Washington a week earlier in a December 8th Address to Congress, the country and its new federal government were flourishing.

Under Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton’s financial plan, “the progress of public credit is witnessed by considerable rise of America stock abroad as well as at home.” Historian Ron Chernow indicates that the “peaceful interlude” in American politics, which followed the bitter disputes over the location for the new capital and Hamilton’s financial program, saw the value of federal bonds tripling in value as confidence in the “public credit” was restored.

Six months earlier, if Thomas Jefferson’s account is to be believed, a more famous meeting took place on June 20th at Jefferson’s New York residence on Maiden Lane. The Residence Act was adopted on July 10 as a result of the compromise hammered out between Hamilton, Madison and Jefferson, providing for the establishment of a new capital, followed on July 26 by Hamilton’s plan for the assumption of state debt. The grand compromise was memorialized by Lin-Manuel Miranda’s “Room Where it Happens.” Not long thereafter, Congress held its farewell session in New York’s Federal Hall on August 13, with the requirement that all federal offices relocate to Philadelphia by the first Monday in December, 1790.

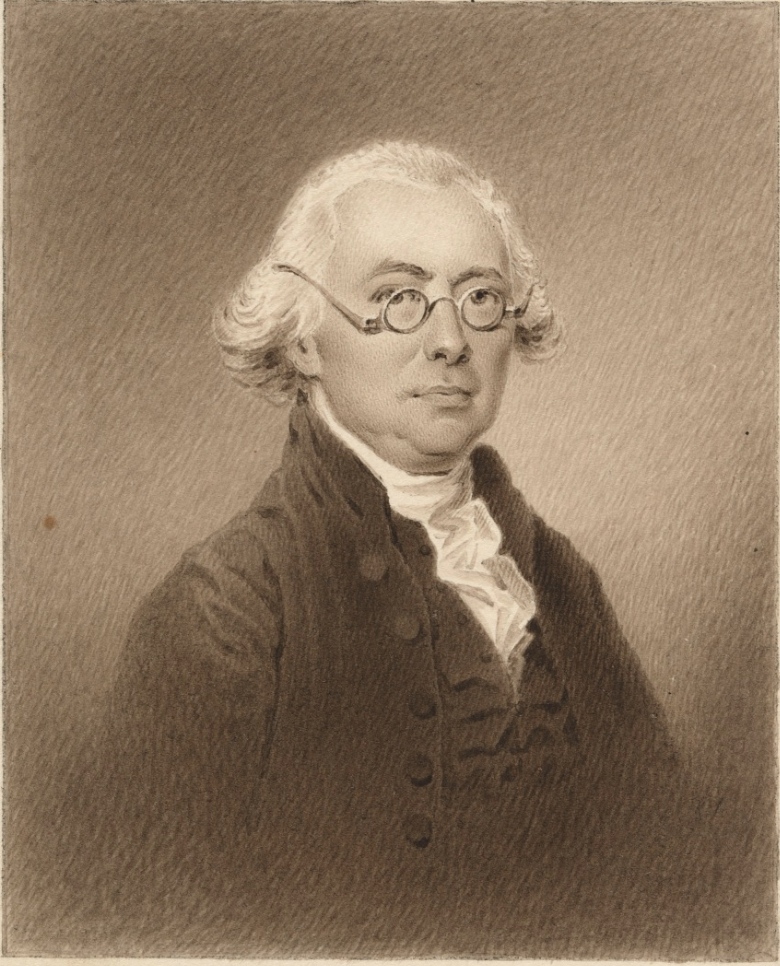

Who was James Wilson ?

When Wilson presented his December 15, 1790 lecture he was speaking as a Professor, Associate Supreme Court Justice and highly respected legal authority. Not surprisingly, Wilson was known for his reputation as a “teaching” justice, as his opinions were written as if they were lectures. As one of the original six justices appointed to the Supreme Court by Washington, early cases provided an opportunity to address sections of the Constitution that he helped write, particularly those implicating the role of a strong central government.

Wilson knew that of which he spoke, as he was one of only six founders that signed both the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence. During the summer of 1787, he served on the important Committee of Detail that prepared the first draft of the Constitution. He was also a drafter of Pennsylvania’s Constitution of 1790. His revolutionary credentials date back to 1774 when he published the important pamphlet “Considerations on the Nature and Extent of the Legislative Authority of the British Parliament,” arguing that radical position that Parliament lacked authority over the colonies without their consent:

All men are, by nature, equal and free: no one has a right to any authority over another without his consent: all lawful government is founded on the consent of those who are subject to it: such consent was given with a view to ensure and to increase the happiness of the governed, above what they could enjoy in an independent and unconnected state of nature. The consequence is, that the happiness of the society is the first law of every government.

Thomas Jefferson would use passages from Wilson as a source for the Preamble of the Declaration of Independence, which in Jefferson’s original rough draft provided that: “We hold these truths to be sacred & undeniable; that all men are created equal and independent, that from that equal creation they derive rights inherent & inalienable, among which are the preservation of life, & liberty & the pursuit of happiness.”

During the Constitutional Convention Wilson stood out as an ardent nationalist along with Hamilton, Madison and Gouverneur Morris. With the exception of Morris, no delegate spoke more during the Convention than Wilson, who spoke at least once every day (168 times) beginning on May 31, 1787.

Among other things, Wilson was a believer in national authority based on popular sovereignty. Wilson also advocated for a single national executive, with veto power, elected for one year terms, and eligible for re-election. As a delegate from the large state of Pennsylvania, he worked with Madison to advance the Virginia plan of proportional representation. Indeed, the Pennsylvania and Virginia delegations worked closely together to formulate strategy in the early days of the Convention when other delegates were late arriving. Some historians credit Wilson with coining the phrase “We, the people” which was used by Gouverneur Morris in the Preamble to the Constitution.

According to Madison’s notes on May 31, 1787:

Wilson contended strenuously for drawing the most numerous branch of the Legislature immediately from the people. He was for raising the federal pyramid to a considerable altitude, and for that reason wished to give it as broad a basis as possible. No government could long subsist without the confidence of the people. In a republican Government this confidence was peculiarly essential. He also thought it wrong to increase the weight of the State Legislatures by making them the electors of the national Legislature. All interference between the general and local Governm[ents] should be obviated as much as possible.”

Fellow signer of the Declaration of Independence, Benjamin Rush, described Wilson as a “blaze of light.” Co-delegate to the Constitutional Convention, William Pierce, described Wilson as follows:

Mr. Wilson ranks among the foremost in legal and political knowledge….Government seems to have been his peculiar study, all the political institutions of the world he knows in detail, and can trace the causes and effects of every revolution from the earliest stages of the Grecian commonwealth down to the present time.

In addition to his prominent role drafting the Constitution, Wilson also played a leading role in the ratification process. His influential and widely re-printed State House Yard Speech on October 6, 1787, is generally recognized as the first public defense of the Constitution. While the Federalist Papers are more famous, Wilson’s early speech had more impact in the ratification campaign. Wilson argued that the Constitution was not a threat to the states and that the federal government’s taxing powers were necessary as a matter of national security. As described by Wilson, the Constitution’s opponents were self-interested beneficiaries of the status quo. According to historian Gordon Wood the speech was nothing short of “the basis of all Federalist thinking.”

In its early days, the Supreme Court did not hear many cases. Wilson’s most famous case was Chisholm v. Georgia (1793), holding that individuals could sue states in federal court. The ratification of the Eleventh Amendment in 1795 reversed the Court’s ruling.

After being appointed by President Washington, Wilson served on the Supreme Court from 1789 until his death in 1798 at the age of 55. Tragically, Wilson’s final years were punctuated by financial difficulties and failed land speculation. Unable to renegotiate large debts on land in western Pennsylvania, New York and Georgia, he was wiped out by the Panic of 1796-1797. Wilson suffered the fate of several other founders, including Robert Morris and Lighthorse Harry Lee, who spent time in debtors prison near the end of their lives, although Wilson was imprisoned as a sitting Supreme Court Justice.

In 1906, President and historian, Theodore Roosevelt sparked renewed appreciation for Wilson during the dedication of Pennsylvania’s new capital building in Harrisburg. Following Roosevelt’s speech, Wilson’s remains were removed from North Carolina and reinterred at Old Christ Church in Philadelphia.

An Introductory Lecture to a Course of Law Lectures by James Wilson

Professor James Wilson’s address on December 15 was the first of a series of fifty-eight lectures that he prepared as the first professor of law at the College of Philadelphia, one of the nation’s first formal law schools along with the College of William and Mary Law School in Virginia.

Wilson’s lecture series at the College of Philadelphia offered a wide-ranging analysis of legal systems dating back to Greece and Rome. He covered an array of subjects including natural law, common law, and international law. In his final lectures he covered the new American Constitution, including the passage cited by President Trump’s defense lawyers.

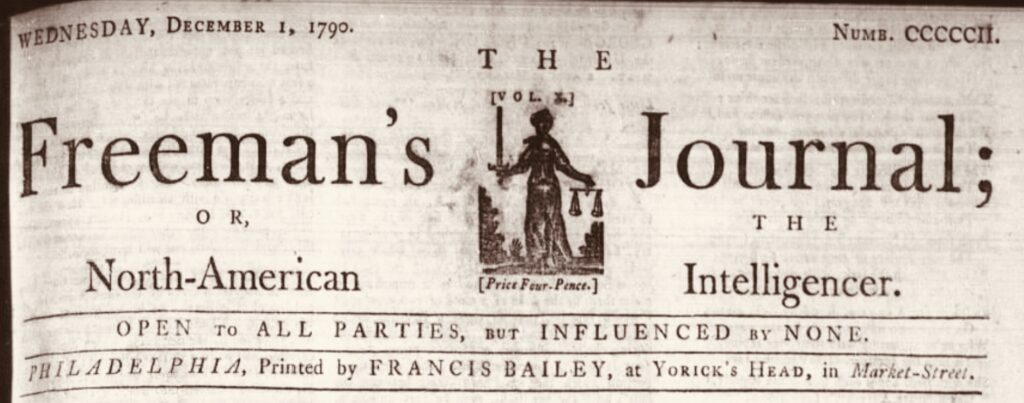

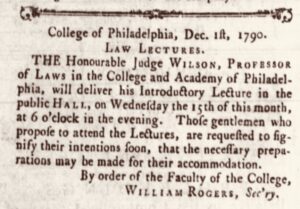

Interestingly, the invitation to the inaugural lecture didn’t mention that Wilson was a Supreme Court Justice. Copied below is the announcement of the lecture, which was printed in several Philadelphia newspapers.

Wilson December 15 introductory lecture was intended for a broad audience, including invited guests. It is likely that several prominent women attended. For example, one can surmise that Martha Washington may have sat next to Eliza Hamilton? While many secondary sources opine that Washington’s cabinet attended, Statutesandstories.com has not yet been able to locate any primary sources verifying that Secretary of State Jefferson, Treasury Secretary Hamilton, Secretary of War Knox, or Attorney General Randolph attended. Nevertheless, it is clear that they were living in Philadelphia, the nation’s new capital at the time. Indeed, Hamilton had just submitted to Congress his famous Second Report on Public Credit proposing the creation of a national bank.

Wilson began his lecture describing that he was pleased to speak before an audience which included women:

Ladies and Gentlemen, Though I am not unaccustomed to speak in publick, yet, on this occasion, I rise with much diffidence to address you. The character, in which I appear, is both important and new. Anxiety and selfdistrust are natural on my first appearance. These feelings are greatly heightened by another consideration, which operates with peculiar force. I never before had the honour of addressing a fair audience. Anxiety and selfdistrust, in an uncommon degree, are natural, when, for the first time, I address a fair audience so brilliant as this is. There is one encouraging reflection, however, which greatly supports me. The whole of my very respectable audience is as much distinguished by its politeness, as a part of it is distinguished by its brilliancy. From that politeness, I shall receive—what I feel I need—an uncommon degree of generous indulgence.

Wilson continued:

In a free country, every citizen forms a part of the sovereign power: he possesses a vote, or takes a still more active part in the business of the commonwealth. The right and the duty of giving that vote, the right and the duty of taking that share, are necessarily attended with the duty of making that business the object of his study and inquiry.

The following year, Wilson published his December 15, 1790 lecture under the title An Introductory Lecture to a Course of Law Lectures, published by T. Dobson in Philadelphia in 1791. Vice President John Adams recommended that his sons attend Wilson’s lectures in a letter dated December 4, 1790 to Charles Adams.

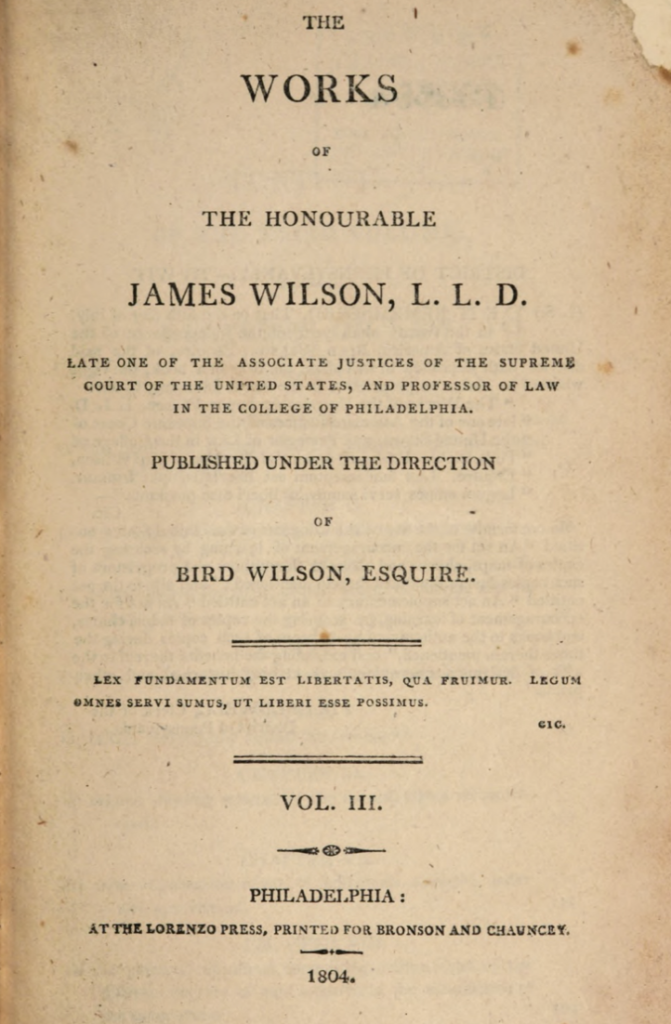

Following Wilson’s death in 1798, his son, Bird Wilson, published his lectures in 1804 in a three volume edition copied below. Excerpts from his lectures were also contemporaneously published in the American Museum and the Columbia Magazine in January 1791 (Introductory lecture), December 1790 (Second Lecture).

Citation of Wilson’s lectures during Trump Impeachment

On February 12, 2021 President Trump’s attorney Michael Van der Veen cited Wilson’s lectures, arguing that “lawful and constitutional conduct may not be used as an impeachable offense.” Wilson’s lectures were also cited on pages 40-41 of President Trump’s Trial Brief.

Discussing impeachment Wilson wrote that:

The doctrine of impeachments is of high import in the constitutions of free states. On one hand, the most powerful magistrates should be amenable to the law: on the other hand, elevated characters should not be sacrificed merely on account of their elevation. No one should be secure while he violates the constitution and the laws: everyone should be secure while he observes them.

Whether this statement actually supports the defense theory is beyond the scope of this post. Here is a link to the House Managers’ Reply Brief.

Additional Reading:

University of Pennsylvania’s first campus in 1790

James Wilson and the Constitution, Burton Konkle (1907)

The Works of the Honorable Jame Wilson, Volume I (Bird Wilson, 1804)

The Works of the Honorable James Wilson, Volume II (Bird Wilson, 1804)

The Works of the Honorable James Wilson, Volume III (Bird Wilson, 1804)

James Wilson on the Authority of the British in North America, J Mark Alcorn (2010)

Law and Democracy: The Philosophy of James Wilson, Roberta Bayer (Law&Liberty.org)

James Wilson (MountVernon.org)

James Wilson: A Forgotten Father, Gerard J. St. John