Background about the “Constitution’s cover letter”

On the final day of the Constitutional Convention, thirty-nine delegates lined up to sign the Constitution. As his last formal act as the presiding officer of the historic Convention, George Washington signed a little known cover letter that would introduce the Constitution to the world.

Although their secretive work in Philadelphia was concluding, the next chapter in the national saga was just beginning. At this point the Constitution was merely a proposal. It would need to be ratified by nine states before it could take effect. As the delegates fully understood, by no means was this outcome guaranteed. Washington himself would privately acknowledge that “much will depend” on the abilities of its advocates and their “good pens” in the months to follow.

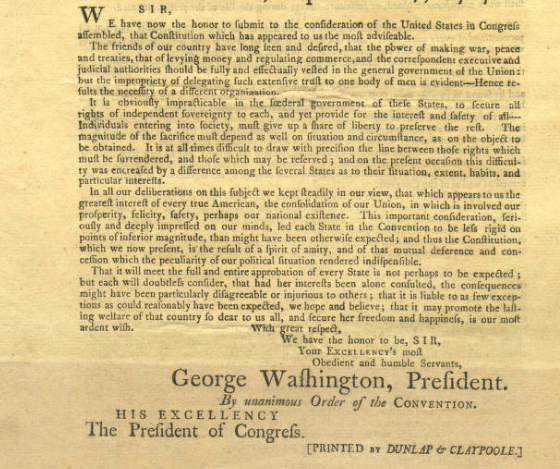

History has largely overlooked the cover letter which transmitted the proposed Constitution from the Constitutional Convention (meeting in Philadelphia) to the Confederation Congress (meeting and residing in New York). Click here for a link to the cover letter. The five paragraph introductory cover letter was signed by future President Washington on September 17, 1787, but has largely been forgotten. This post explains why the cover letter deserves to be “uncovered” and studied. Its message and reasoning will surely resonate with modern audiences, as the founders no doubt intended.

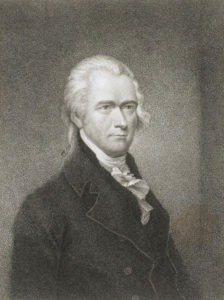

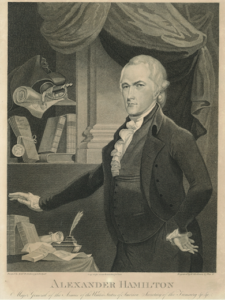

This post is divided into four parts. Part I provides background about the September 17 cover letter. Professor Daniel Farber rightly describes the document as “the Constitution’s forgotten Cover Letter.” As argued below, the letter is historically significant, but has been under-appreciated for too long. Part II theorizes that the September 17 cover letter was primarily, if not exclusively, written by Alexander Hamilton. The pending proof for Hamilton’s authorship of the Constitution’s cover letter (hereinafter the “Hamilton Authorship Thesis”) will come as no surprise to Hamilton scholars and fans, who know that Hamilton’s work has been under-appreciated for far too long.

Part III explains the significance of the cover letter and the unrecognized role it played during the ratification process. It was the “most ardent wish” of the Framers that copies of the Constitution and its accompanying cover letter would be sent by Congress to the states. Before the explanatory cover letter was signed by Washington, it was read aloud and officially approved “by paragraphs.” This fact places the official letter on par with few other acts of national deliberation. Nine months later, the Constitution’s four pages of parchment would become law.

Part IV identifies unanswered questions which historians and researchers are invited to explore for the purposes of testing, supporting, or disproving the “Hamilton Authorship Thesis.” It is the earnest wish of this author that the provenance of the cover letter will be fully and rigorously examined.

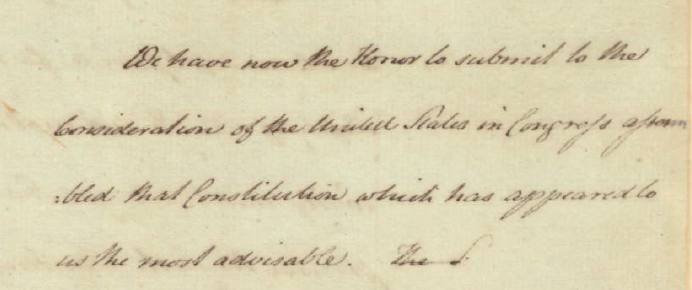

Paraphrasing the cover letter, “[I] have now the honor to submit to the consideration” of my friends and colleagues the “Hamilton Authorship Thesis.” That this post (and the pending articles) will “meet the full and entire approbation of every state is perhaps not to be expected.” Nevertheless, I “hope and believe” that scholarly analysis of the Constitution’s cover letter will be “most advisable.” This exercise will serve to promote the goal of education about our Constitution, the Framers, and their glorious story. Doing so is intended to “promote the lasting welfare of the country so dear to us all.”

Howard Chandler Christy’s Scenes of the Signing of the Constitution

Background about the cover letter

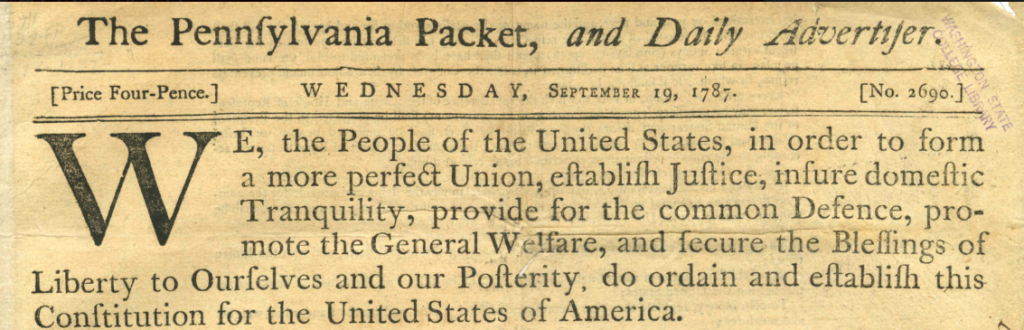

When the Constitution was first released to an anxious public, the widely disseminated transmittal letter was commonly printed together with the Constitution. The country’s newspapers, broadsides, and gazettes rushed to print the entire Constitution, along with its cover letter. Due to the relative brevity of both documents, they fit together in a single issue of the the four-columned papers of the day. According to Professor Robert Rutland, “Nothing similar to this had ever occurred before and has never happened since—a whole nation invited, and even encouraged, to read the entire Constitution.”

As intended, the cover letter introduced the Constitution in the newspapers and pamphlets that were being furiously read all across the nation. Publishers prominently displayed the cover letter below the Constitution, following the signatures of the famous delegates. The introductory cover letter would in turn be cited and read aloud at the all important state ratification conventions. Yet, when the Constitution and its cover letter were re-printed in New York in the months leading up to New York ratification convention in 1788, the cover letter was prominently printed ahead of Constitution (more on this later in Part II).

The Constitution was first released to the world on September 19, 1787. Philadelphia’s Pennsylvania Packet published the Constitution and its cover letter shortly after the Convention concluded its work. The Convention’s printers, Claypoole and Dunlap, had covertly prepared working drafts of the Constitution for the delegates during the Convention. Upon receiving word that the Constitution was signed, they quickly put their presses into motion. The day’s newspaper was dedicated entirely to the Constitution. All other news was abandoned to allow a full length printing of the Constitution, alongside the September 17 cover letter, which is pictured below.

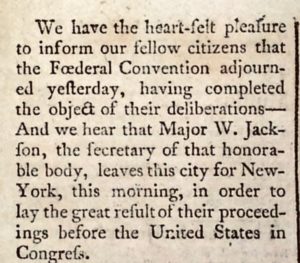

The signed Constitution and its cover letter were delivered to the Confederation Congress in New York by Major William Jackson, the Secretary of the Philadelphia Convention. Copied below is a short report in the Pennsylvania Packet on September 18 that the “Federal Convention adjourned yesterday, having completed the object of their deliberations.” The article further reports that Secretary Jackson departed Philadelphia for New York to deliver the Constitution.

The cover letter would be read aloud three days later in New York at the Confederation Congress on September 20. Would Congress agree with the Philadelphia Convention’s request to begin a new experiment in democracy? Or would the increasingly vocal and mobilizing anti-federalists convince the public that the proposed ratification process was invalid and unwise?

How is the cover letter described by historians?

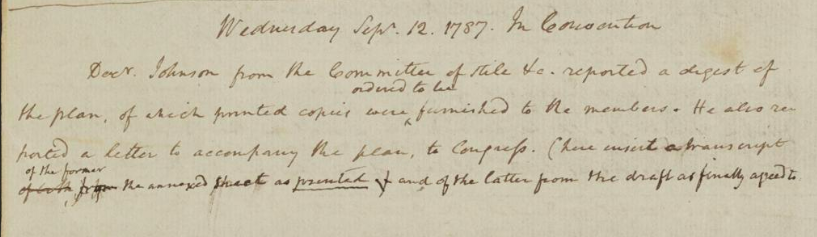

How should the cover letter be described? The cover letter was signed by Washington, making it “Washington’s letter.” The letter was “reported” out on September 12 by Chairman William Samuel Johnson’s five-member Committee of Style (more on the Committee later), so it was also the Committee’s letter. According to James Madison’s notes of the Convention, the cover letter “was read once throughout, and afterwards agreed to by paragraphs,” making it an official document of the Constitutional Convention.

In less than four days, the Committee of Style simultaneously produced four key documents: i) the final draft of the Constitution, ii) the Constitution’s cover letter, and iii) two critical procedural resolutions which outlined a ratification process for the states to follow.

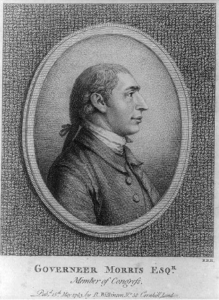

Gouverneur Morris is widely acknowledged as having masterfully re-written, re-organized, and re-packed, the final draft of the Constitution. Focusing on its content, Professor Farber refers to the cover letter as a “consensus document.” But many historians also credit Morris with having written the cover letter when he was completing the final draft of the Constitution. While the cover letter may have been in Morris’ handwriting (more on this later), the “Hamilton Authorship Thesis” in Part II (pending) asserts that Morris did not “write” the cover letter.

Instead of identifying the cover letter by reference to its author or signer, historian Catherine Drinker Bowen labels the cover letter as “the Convention’s letter to Congress.” In her famous book, Miracle at Philadelphia, Bowen focuses on the “closing appeal” in the last sentence of the letter: “That the Constitution may promote the lasting welfare of that country so dear to us all, and secure her freedom and happiness, is our most ardent wish.”

Writing for the National Constitution Center, Derek A. Webb emphasizes the “guiding spirit” of the Constitution’s cover letter:

When we consider our founding charters, we rarely consider this document, now somewhat lost to history. Rather, we consider those even more august documents under glass in the National Archives in Washington, D.C. We look to the Declaration of Independence as a statement of our guiding principles. And we look to the Constitution as the intricately enacted legal infrastructure designed to advance those principles. But the Constitution’s cover letter deserves to be ranked at least somewhere among those bedrock texts, for it provides a statement of the guiding spirit in which our constitutional architecture was originally assembled.

In a letter written from London in December of 1787, John Adams described the Constitutional Convention as “the greatest single effort of national deliberation that the world has ever seen.” During the four months that the founders struggled with the weighty constitutional questions at stake their proceedings were secret. Indeed, Alexander Hamilton was one of three delegates who drafted the procedural rules governing the Convention, including the veil of secrecy over the summer’s deliberations.

But who on the Committee of Style actually composed the cover letter for Washington’s signature? To date, no authoritative investigation has been made into the authorship of the cover letter. Why is the Constitution’s transmittal letter effectively unknown to modern audiences? What reasons did the framers proffer to justify the revolutionary new government that was being proposed? What did the cover letter’s drafter(s) intend to communicate by referring to the “spirit of amity” at the Convention? What does its message mean today?

Objectives of the Cover Letter

The September 17th cover letter represents the opening effort by the weary Founders to introduce their handwork to the world. One would expect that they knew that their cover letter – signed by the beloved hero of the Revolutionary War – would be the first thing that the anxious public would consider when scrutinizing the Constitution. This article argues that Washington’s cover letter should not be viewed as a mere formality. Rather, the cover letter was significant in its own right for the message that it was carefully crafted to convey. This article tells its overlooked story.

After four months of intense but productive deliberations, the framers of the Constitution concluded their work on September 17, 1787. The thirty-nine exhausted and home-sick delegates who signed the Constitution organized themselves from north to south according to their state delegation. On that day they represented not only their individual states, but the future of a constitutional republic that much of the world expected to fail. The image is etched in our memory, as depicted in the painting entitled the Scene at the Signing of the Constitution of the United States by Howard Chandler Christy.

Of the fifty-five founders who attended the Philadelphia Convention during the summer, only forty-two stayed through the close of the Convention. Despite a plea by Alexander Hamilton and a now famous speech by Benjamin Franklin, three Founders refused to sign the Constitution on September 17, 1787. Other participants, including all of Alexander Hamilton’s co-delegates on the New York delegation, had departed Philadelphia in opposition to the nationalist project. The Founders who did sign knew that George Mason, the drafter of the Virginia Bill of Rights, outspoken New Englander, Eldridge Gerry, and Virginia Governor Edmund Randolph would be opposing ratification as they pushed for a second convention. Click here for a discussion of the anti-federalists and the Bill of Rights.

Thus, the purposes of the Constitution’s cover letter included: 1) introducing the Constitution to America, 2) explaining and justifying why the new Constitution was necessary (the how and why), 3) requesting and persuading Congress to send the Constitution to the states for ratification, 4) initiating the national campaign for ratification, 5) setting the tone for the political battle that was about to begin, 6) urging supporters and critics to rise above partisan politics for the greater good by inculcating a “spirit of amity” and cooperation, 7) sending a symbolic message that Washington would be willing to serve as President, and 8) rallying the country together under Washington’s leadership. After all, who would be willing to oppose the Constitution if the Convention was led by Washington and Franklin, two of the nation’s most respected Americans?

As described by Catherine Bowen, the cover letter is:

a most skillful and touching document which breathes confidence in what the Convention achieved, makes no apologies but tells with seriousness and humility just what such a convention of diverse states felt it could and could not do.

In other words, the cover letter was a marketing device intended for several audiences. At the outset, the letter was addressed to the Confederation Congress and its President, Arthur St. Clair. Secondarily, the letter was intended to speak to state legislatures which needed to be convinced to follow the proposed ratification road map. Arguably the most critical audience was the state ratifying conventions. Of course, the letter was also written for the American people, the world, and posterity. Accordingly, the message of the cover letter needed to be pragmatic, symbolic, and persuasive. But who would draft it?

Authorship Issue

Historians have routinely attributed authorship of the Constitution’s cover letter to Gouverneur Morris. The so-called “penmen” of the Constitution, Morris is universally credited with the Constitution’s organization, polish and style. The historical record is clear that Morris was charged with the task of preparing the final draft of the Constitution. Madison, the “Father of the Constitution,” credits Morris’ role in a letter to Harvard President Jared Sparks. Madison freely acknowledged that a “better choice [than Morris] could not have been made.”

While re-writing and organizing the Constitution, Morris also re-drafted the preamble. The prior draft inherited by Morris began by listing the individual states by name. Morris transformed the preamble to recognize that the Constitution was established by “We the People of the United States,” rather than a yet uncertain list of states. Historian Joseph Ellis refers to Morris’ phraseology as “probably the most consequential editorial act in American history.”

No serious scholar doubts that Morris was assigned the task of re-drafting and finalizing the Constitution by the Committee of Style and Arrangement. In his biography of Gouverneur Morris, William Howard Adams also presumes that Morris wrote the official letter in “Morris’s best diplomatic gloss.” Gouverneur Morris: An Independent Life at 165 (2003).

Moreover, some may have confused letters written by state delegations to their respective legislatures with the Convention’s official cover letter. In his book, A More Perfect Union: The Making of the United States Constitution, William Peters opines at page 216 that Morris, Franklin and Jared Ingersoll (all members of the Pennsylvania delegation) wrote the cover letter. But as will be discussed below and in pending posts, the conventional wisdom that Morris wrote the September 17 cover letter is wrong.

When compiling the Records of the Federal Convention in 1913, Max Farrand opined that the cover letter “is in the handwriting of Gouverneur Morris.” Catherine Bowen agrees that the letter “has come down to us in Gouverneur Morris’s handwriting.” Yet, this is not dispositive of the authorship of the cover letter if Morris merely served as Hamilton’s scribe when recopying the letter for the Convention.

Is it presumptuous to argue that historians have been incorrect for generations? Starting in 1832, Morris biographers have included Harvard President and historian Jarred Sparks. President Teddy Roosevelt wrote a biography of Morris in 1888. Neither Roosevelt nor Sparks, however, discussed the cover letter. More recently, Richard Brookhiser only devotes a single chapter to the drafting of the Constitution in his very readable biography, Gentleman Revolutionary: Gouverneur Morris – The Rake Who Wrote the Constitution. Thus, these well respected scholars have simply not addressed the authorship of the cover letter. Although Morris kept a diary when he was appointed ambassador to France by Washington, he was too busy during the Constitutional Convention to record contemporaneous notes.

Notwithstanding the long held conventional wisdom that Morris “wrote” the Constitution’s cover letter, there is overwhelming evidence for the Hamilton Authorship Thesis. Unlike many of the more famous founders with easy to pronounce names, Gouveneur Morris’ life has been studied by less than a dozen biographers. While several of these historians have brought tremendous scholarship and talents to bear to tell the complex story of Morris’ life, none have focused their energies investigating the identity of the cover letter’s author.

The Hamilton Authorship Thesis will be discussed in detail in Part II of this post. A pending scholarly article is also being being finalized, subject to peer review. Set forth below is an overview of the Hamilton Authorship Thesis.

Overview of “Hamilton Authorship Thesis”:

Hamilton’s work prior to the Philadelphia Convention

Remarkably, as early as 1780, when most were focused on winning the Revolutionary War and defeating the British, Alexander Hamilton was thinking ahead about nation building. As described below, Hamilton’s correspondence and recommendations in the years leading up to the Philadelphia Convention provide powerful clues that he wrote the cover letter.

In his letter to Congressman James Duane dated September 3, 1780, Hamilton began digesting the fundamental defects with the Articles of Confederation. Hamilton understood that the “common sovereign will not have power sufficient to unite the different members together, and direct the common forces to the interest and happiness of the whole.” This theme would carefully appear in the cover letter seven years later, which asserted that it is “impracticable in the federal government of these states, to secure all rights of independent sovereignty to each.”

In particular, in his 1780 letter to Duane Hamilton argued that Congress should be given “complete sovereignty in all that relates to war, peace, trade, finance, and to the management of foreign affairs,” along with other powers. This aligns with the 1787 cover letter’s statement that friends of the country had long desired that the “power of making war, peace, and treaties, that of levying money and regulating commerce” should be vested in the general government of the Union.

In 1781, in a voluminous proposal to Robert Morris (no relation to Gouverneur Morris), Hamilton laid out a comprehensive vision for a new financial system. At the time Robert Morris was Superintendent of Finance under the Articles of Confederation. Hamilton would eventually replace Robert Morris in 1789 as America’s first Secretary of Treasury. In his 1781 letter, Hamilton argued that correcting the defects in the government’s revenues and credit was “indispensably necessary.” The 1787 cover letter likewise argued that action was “indispensible.”

From 1781 to 1782 a series of essays began appearing in the newspaper, The New-York Packet. Writing under his pseudonym “The Continentalist,” Hamilton began describing the want of power in Congress and examining the conflict between “sovereignty” and “liberty” in federal governments “relative to the common interest and safety.” Years later, echoing The Continentalist essays, the cover letter explained that, “[I]t is obviously impracticable in the federal government of these states, to secure all rights of independent sovereignty to each, and yet provide for the interest and safety of all — Individuals entering into society, must give up a share of liberty to preserve the rest.”

Hamilton’s papers contain an un-submitted Resolution that he prepared in 1783 for the Confederation Congress, calling for a convention to amend the Articles of Confederation. At the time the Confederation Congress was meeting in Princeton, New Jersey. Hamilton’s notation indicates that the resolution was “abandoned for want of support.” Again, Hamilton diagnosed the “defects” with the Articles, but he was too far ahead of his time.

Among other things, Hamilton’s un-submitted resolution raised the following complaint: “legislative executive and judicial authorities should be deposited in distinct and separate hands.” The cover letter contains the identical terminology, explaining that “the correspondent executive and judicial authorities should be fully and effectually vested in the general government of the Union.”

One of the central themes in the September 17, 1787 cover letter is praise for the “spirit of amity, and of that mutual deference and concession” that produced the Constitution. Hamilton’s 1783 Resolution attempted to invoke “a spirit of compromise.” Yet, not until June 21, 1788, would the required ninth state (New Hampshire) ratify the Constitution thereby fulfilling the “spirit of compromise” that Hamilton had called upon years earlier.

In 1786, Hamilton and Madison were the leading proponents of a stronger national government at the Annapolis Convention. Indeed it was Hamilton who wrote the Annapolis Convention report calling for the convening of a Convention in Philadelphia. Tellingly, Hamilton’s Annapolis Convention report described the political “situation” under the Articles as “delicate and critical.” In the cover letter, the author similarly refers to the “peculiarity of our political situation” which rendered rendered compromise “indispensible.” Moreover, in 1786 Hamilton called for action “effectually to provide for the exigencies of the Union.” This language is replicated in the cover letter’s intent that power be “effectually vested in the general government of the Union.”

During the Constitutional Convention Hamilton departed Philadelphia on June 30 to attend to business in New York. Except for a brief appearance in August, he did not return until early September. Importantly, while Hamilton was in New York he was taking the political temperature in his home state. His fellow New York delegates, John Lansing and Robert Yates, believed that the Framers were exceeding their instructions to rewrite, not replace the Articles. After six weeks, Landing and Yates left the Convention in protest and would send a joint letter to New York Governor George Clinton prior to the New York Convention. Hamilton knew well that these three prominent New Yorkers were opposed to the Constitution and would present formidable adversaries at the New York ratification convention.

Recognizing the obstacles that Clinton and his fellow New York delegates would present, Hamilton began a letter writing campaign in July in New York to begin building public support. Click here for a link to Hamilton’s letter to New York’s Daily Advertiser. Two days prior to the signing of the cover letter, Hamilton wrote another letter to the Daily Advertiser on September 15 as part of the brewing public relations battle in New York. Thus, in September of 1787 Hamilton was already engaged in the public relations campaign that would consume the nation for the next year. Of course, more than anyone, he was prepared for the assignment, since he had been advocating for an effective federal government since 1780.

Overview of “Hamilton Authorship Thesis”:

“Committee of Style Division of Labor Hypothesis”

In the final days of the Philadelphia Convention, the Committee of Style and Arrangement was appointed to synthesize and finalize the Constitution. On the evening of September 8th the Committee convened for the first time. Four days later, on the morning of September 12, Committee Chairman Johnson reported their work to the Convention: i) Morris’ revised draft of Constitution, ii) the cover letter, and iii) two resolutions setting for the proposed ratification process.

The Convention selected five heavyweights among giants to serve on the Committee. In his book, The Genius of the People at page 268, Charles Mee describes the five committee members as follows:

Five members were appointed to the committee: the practical Rufus King, the mastermind Madison, the conciliatory Connecticut delegate Johnson, and the two great prose stylists in the hall, Gouverneur Morris and Alexander Hamilton.

The “Committee of Style Division of Labor Hypothesis” set forth for the first time below proposes that these five members divided up the Committee’s work based on each member’s expertise. The hypothesis proposes that the Committee recognized that the Constitution’s cover letter was not a mere formality. Rather, drafting the cover letter for Washington’s signature fit perfectly within Hamilton’s wheelhouse. As will be explained in more detail in Part II, this hypothesis proposes that:

- Hamilton was charged with drafting the cover letter,

- Rufus King was responsible for drafting the two resolutions,

- Morris, as we know, focused on the body of the Constitution and the preamble,

- Madison with his notes of the Convention in hand assisted all of the members (particularly Morris) to make sure that the Committee’s work did not run afoul of earlier votes. This function for Madison was particularly important since both Hamilton and Morris (to a lesser extent) had been absent for portions of the Convention; and

- Johnson, the Chairman and oldest member of the Committee, supervised the operation.

Historian Catherine Bowen writes that, “one of the cleverest things they did was to delete altogether the controversial Articles XXII and XXIII concerning ratification and put them in the form of two resolves,” which followed behind the text of the Constitution.

The Committee of Style Division of Labor Hypothesis asserts that Rufus King drafted the resolutions because he was the primary force behind the ratification strategy. Earlier in the Convention, King devised the practical solution that the Constitution would take hold in the states that ratified it, provided that nine states agreed. King made the motion on August 31 to revise Article XXI by adding the words “between the said States” “so as to confine the operation of the Govt. to the States ratifying it.”

On the August 30 session, Daniel Carroll of Maryland had made a motion that all thirteen states would be required to ratify the Constitution. Rufus King’s biographer, Robert Ernst, summarizes King’s primary role on this subject:

King…proposed the next day that the operation of the new government be limited to those states which ratified the Constitution, a practical solution to the problem that Carroll had raised. The delegates overwhelmingly approved…

As for the method of ratification, King also had a workable solution. Leaving ratification to the state legislatures allowed the self interested status quo to undermine the proposed Constitution. King argued that leaving ratification up to the legislatures was “equivalent to giving up the business altogether.” King understood that the convention process would avoid playing into the hands of the enemies of the Constitution. According to Madison’s notes, King also “observed that the Constitution of Massachusetts was made unalterable till the year 1790, yet this was no difficulty with him. The State must have contemplated a recurrence to first principles before they sent deputies to this Convention.”

It is also useful to point out that the Committee members may not have been exclusively focused on Committee work from September 8th to 12th. For example, Morris was called upon by his fellow Pennsylvania delegate, Ben Franklin, to review Franklin’s speech that would be given on the final day of the Convention.

Morris’ work on the final draft of the Constitution was extraordinary enough. Presuming that Morris also drafted the Constitution’s cover letter fails to do justice to the majesty of the extraordinary document. Testing the conventional wisdom need not detract, however, from Morris’ legacy. Ultimately the five member Committee on Style reported out the cover letter for the entire Convention’s review. Thus, the letter is the work of the entire Committee, the Convention, and its signatory, Washington. But the Hamilton Authorship Thesis asserts that it was primarily, if not exclusively, drafted by Hamilton.

Overview of “Hamilton Authorship Thesis”:

The Mountain of Inferential Evidence

The overwhelming evidence for the Hamilton Authorship Thesis can be organized into the following inter-related and self reinforcing categories, which will be discussed in detail in Part II (pending):

First, none of the other four members of the Committee on Style (Morris, Madison, King, or Johnson) ever claimed authorship of the letter. This is noteworthy because despite their oath of secrecy, Morris did eventually admit his role in preparing the final draft of the Constitution. Referring to the Constitution, Morris acknowledged “That instrument was written by the fingers, which write this letter.” Click here for a link to Morris’ letter to Timothy Pickering. Importantly, Morris did not claim authorship of the cover letter. In the same letter, Morris further admitted that he did not take notes at the Convention, a task that was delegated to Madison.

Similarly, in 1831 Madison acknowledged and complemented Morris’ work on the final draft of the Constitution. According to Madison’s letter to Sparks, “the finish given to the style and arrangement of the Constitution, fairly belongs to the pen of Mr. Morris.” Importantly, Madison in his glowing praise for Morris never suggested that Morris drafted the cover letter. Georgia delegate, Abraham Baldwin, is reported to have claimed that Morris had “the chief hand in the last arrangement and composition” of the Constitution. This account likewise does not claim credit for the cover letter. Diary of Ezra Stiles reporting conversation with Baldwin.

Second, the cover letter is written in Hamilton’s unmistakable style, using Hamilton’s terminology, terms of art, and ideas. The striking examples of Hamiltonian fingerprints on the cover letter will be detailed in Part II. By way of example only, the following phrases in the cover letter can be found repeatedly in Hamilton’s papers, including some of his most recognized work. By contrast, these words and phrases do not appear with the same frequency (or at all) in the correspondence of the other Committee members: “friends of our county,” “most advisable,” “is evident,” “levying money,” “Hence results the necessity,” “deeply impressed,” “hope and believe,” “will doubtless consider,” “spirit of amity,” “prosperity and felicity,” and “freedom and happiness.”

Beginning in 1774 as a student at King’s College, Hamilton began writing under the pseudonym “A Friend to America.” In his famous Farmer Refuted essay in 1775, Hamilton used the pseudonym “A sincere Friend to America.” The second paragraph of the cover letter begins by describing that “friends of our country have long seen and desired” the defects of the Articles of Confederation. The Hamilton Authorship Thesis stipulates that this purposeful phrase in the cover letter was an autobiographical reference by Hamilton. Some might call this a purposeful “easter egg” hidden in plain sight by ‘the foremost pamphleteer” in American history.

One of the main messages in the cover letter was the “spirit of amity… mutual deference and concession” which occurred in Philadelphia. Who represented that spirit of compromise more than Hamilton? When Hamilton encouraged all delegates to sign the Constitution on September 17, he admitted that “No man’s ideas were more remote from the plan than his were known to be; but is it possible to deliberate between anarchy and convulsion on one side, and the chance of good to be expected from the plan on the other.” Click here for a link to Madison’s notes.

Sadly, in one of his last letters preceding his death, Hamilton composed his Statement on Impending Duel with Aaron Burr. Summarizing his wishes and regrets about the approaching duel, Hamilton wrote that it is “my ardent wish that I may have been more mistaken than I think I have been, and that he by his future conduct may shew himself worthy of all confidence and esteem, and prove an ornament and blessing to his Country.” Hamilton also used the same phrase in his famous Report on Manufacturers. Washington, however, regularly used the phrase in his correspondence, particularly after Hamilton joined his staff in 1777. One can reasonably assume that both were very familiar with the circumstances when this particular – and emphatic – phrase was acceptable to Washington.

The cover letter was purposely crafted to be signed by Washington. During the Revolutionary War “the Pen of our Army was held by Hamilton.” In his biography of Washington, historian Joseph Ellis observes that Washington linked together two founding moments in American history: the fight for independence and the effort to secure it. His Excellency: George Washington. Who better than Hamilton to write a letter to be signed by Washington?

During the Revolutionary War, Hamilton loyally served as Washington’s trusted aide de camp, regularly writing his correspondence. Teddy Roosevelt in his biography of Morris acknowledges that Hamilton “more than any other man bore the brunt of the fight” for the adoption of the Constitution. Click here for a link to Roosevelt’s biography of Morris. It thus follows that Hamilton would have wanted to be the Constitution’s advocate beginning with the “opening argument” rolled out in the cover letter. Hamilton would also have wanted to write yet another Washington letter. Indeed, Washington may well have assumed that the cover letter would be written by none other than Hamilton. Hamilton scholars and fans will also be quick to point out that Hamilton was not likely to have sat idly by. Hamilton can be expected to have dived head first into his Committee assignment, if not all of the Committee assignments.

To the extent that Hamilton knew that the ratification struggle in New York would be intense, it can be argued that no delegation needed the cover letter more than Hamilton. He was already engaged in a letter writing campaign in the New York papers before the Convention concluded. Shortly thereafter, Hamilton would begin assembling his team to write the Federalist papers.

Interestingly, the cover letter lacks the poetry and rhyme of the preamble and repeats none of its phraseology. This lack of synchronization between the two documents suggests different authorship. Had Morris drafted the cover letter, it is safe to assume that he would have connected the two documents. Yet, none of the expressions in the preamble are contained in the Constitution’s cover letter. Morris referred to the famous contents of the preamble as “a declaration of motives.” If Morris drafted the cover letter, why wouldn’t he include any of the motives for the Constitution in the letter? This question need not be asked if another – Hamilton – wrote the cover letter.

The cover letter is properly understood as the opening salvo in the battle for ratification. It simply did not serve Hamilton’s interest for New Yorkers to know that he wrote the cover letter. As will be discussed in Part II, in the weeks leading up to the New York ratification convention, the cover letter was prominently featured in the New York papers preceding the Constitution. Hamilton no doubt wanted Washington’s signature and symbolism to be foremost in the mind of the delegates. There is also strong evidence that Hamilton could keep secrets. This is particularly the case when Hamilton was working for Washington. There is at least one other story that Hamilton took to the grave. Click here for a discussion of the now well known story of Hamilton’s co-authorship of Washington’s Farewell Address.

To conclude, please excuse the author in imagining the following nostalgic scene. When Washington reviewed the cover letter for the first time he noticed the closing phrase of the letter. Washington reads to himself that “we hope and believe; that it may promote the lasting welfare of that country so dear to us all, and secure her freedom and happiness, is our most ardent wish.” Washington smiles. He know this phrase. It began appearing in his most emphatic correspondence in 1777 when a new lieutenant was added to his staff. He looks at Hamilton and winks. Hamilton smiles. The rest is history.

This post continues in Part II.

Further reading:

Derek A. Webb, The “Spirit of Amity”: The Constitution’s cover letter and civic friendship (Derek A. Webb, National Constitution Center)

Ratification of the Constitution in New York (Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History)

Cover letter for the Mount Vernon Compact (also known as the Compact of 1785) between Virginia and Maryland prepared by George Mason, dated March 28, 1785. [This Compact was ratified by the legislatures of both states and later served as a precedent for similar meetings and agreements.]

“The Rhetoric of Conciliation”, Peter B. Knupfer, in New Perspectives on the Early Republic (edited by Gray and Morrison, 2005)