Questions and Issues for Further Investigation

Before exploring the issues and questions discussed below, readers are invited to review prior posts about the Hamilton Authorship Thesis (the HAT) and the Committee on Style Division of Labor Hypothesis (the DLH).

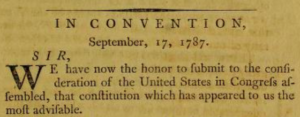

Part I introduces the Constitution’s Cover Letter and the Hamilton Authorship Thesis. Part I provides background about the cover letter and describes its objectives. Part I also explains how the cover letter has largely been “forgotten,” despite its importance during the late 1780s.

Governeur Morris is universally acknowledged as the “penman” of the Constitution. Morris is primarily responsible for finalizing the penultimate draft of the Constitution and the final version of the Preamble. Yet, the Constitution’s cover letter does not cite to the Preamble. Similarly, the style and content of the cover letter does not align with Morris’ work and final “polish” on the Constitution. This disconnect between the two documents suggests separate authorship.

Morris never claimed authorship of the cover letter, but he did proclaim in 1814 that his were the fingers that wrote the Constitution. In 1831, Madison agreed and acknowledged that, “the finish given to the style and arrangement of the Constitution, fairly belongs to the pen of Mr. Morris.” Again, neither Morris nor Madison ever spoke to the authorship of the cover letter.

The HAT offers a ready explanation: Hamilton wanted it this way. The HAT asserts that Hamilton succeeded in concealing his identity for over 230 years. Nonetheless, signature Hamiltonian fingerprints can be found all over the cover letter.

Beginning in 1780, Hamilton wrote detailed proposals along with the popular Continentalist essays that began to make the case for systematic reform of the Articles of Confederation. In 1786, Hamilton authored the report of the Annapolis Convention which called for the convening of the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia. In many respects, it could be argued that Hamilton had been “drafting” the cover letter for almost a decade.

Part II sets forth a detailed presentation of the HAT. In a nutshell the HAT argues that Hamilton was the principal author of the Constitution’s cover letter, which is replete with Hamilton’s linguistic and thematic “fingerprints.” The HAT contends that Hamilton, more than any other delegate, understood the uphill battle that the Constitution would face, particularly in New York. The HAT further suggests that Hamilton, as one of the nation’s foremost polemicists, appreciated the importance of what the cover letter represented.

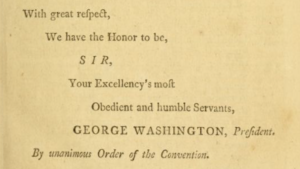

According to Washington, Hamilton was his “principal and most confidential aid.” The HAT proposes that Hamilton was the natural fit to draft the cover letter for Washington’s signature. Not only would Hamilton have wanted to draft the cover letter, Washington may have expected as much. Indeed, Washington may have requested that Hamilton be added to the Committee on Style for this very purpose.

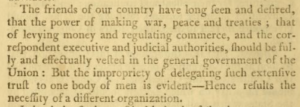

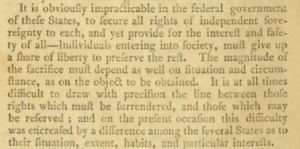

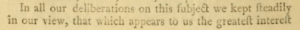

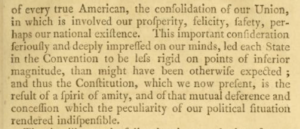

Hamilton understood the symbolic and political value of a cover letter signed by the beloved former Commander in Chief. Ultimately, the cover letter would launch the opening salvo in a national public relations campaign that would grip the nation until the Constitution was successfully ratified in 1788. The HAT also argues that Hamilton used the cover letter as a vehicle to specifically refute objections by Robert Yates and John Lansing. Hamilton’s two co-delegates from New York departed the Philadelphia Convention due to their vocal opposition to the Great Compromise (otherwise known as the Connecticut Compromise between the New Jersey and Virginia plans).

Admittedly, the biggest hurdle for the Hamilton Authorship Thesis is the fact that the only extant draft of the cover letter is not in Hamilton’s handwriting. Assuming for the sake of argument that Morris “wrote” the working draft, the HAT argues that Morris was not the “author” of the cover letter. Rather, the HAT theorizes that Hamilton purposely concealed his identify as the letter was intended for Washington’s signature. As was the case with other Washington letters, Hamilton never publicly revealed his work. He also knew that if his identity became public it would weaken the value of the cover letter during the ratification debates, particularly in New York.

Part III (pending) will explore the importance of the Constitution’s cover letter and the role it played even after the Constitution was ratified.

This post, Part IV, is intended to set forth a range of unanswered questions for historians and researchers. Others, including collectors and archivists might have access to records which are not digitized on the National Archive’s founders.archive.gov website.

There are several ways to contribute to what is intended below to be a “community” project. Statutesandstories welcomes ideas and contributions and wants to afford full credit to others:

- Leave comments below: Unless you instruct otherwise, comments will be listed below in the order received and will be inserted alongside each question/issue as appropriate.

- Send an email: Same concept. Unless you instruct otherwise, ideas and feedback will be inserted alongside each question/issue as appropriate.

- Submit a post: While currently all statutesandstories.com content has exclusively been written by our founder, who knows? We are willing to offer a free platform for other contributors.

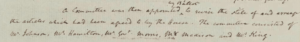

Committee on Style

What we know: We know the identity of the five members of the Committee on Style (Morris, Madison, Hamilton, King and Johnson). We know when the Committee was created (9/8/1787) and when it submitted its report (9/12/1787). Based on Johnson’s diary, we know that the Committee met on at least three occasions (the evening of 9/8, 9/10 and 9/11), but minutes were never taken of Committee meetings. How the Committee operated is thus unclear.

The oldest member of the Committee on Style, William Samuel Johnson, was appointed Chairman. According to Madison, Johnson assigned the “task” of finalizing the Constitution to Morris. This suggests that other “tasks” were assigned to other Committee members.

What we don’t know:

- When and for how long did the Committee meet?

- How did it set its schedule?

- Johnson’s diary records the following, but what do the abbreviations tell us:

Do. In Conventn. . . . 8th. Do. In Conventn. Dind. Mifflins. Eveng. Comee. . . . 10th. Warm. In Convention. & Commee. . . . 11th. Very hot. Do. Do. . . . 12th. Do. Do. Do. Dind. Jacksons . . . . 13th. Rain. Do. Do. . . .

- Did members consult with each other outside of Committee meetings?

- What can we infer from the individual schedules of each of the Committee members?

- Johnson was the least active of the Committee members and likely played a supervisory role. For example, on the day the Committee was formed, Saturday, September 8, Johnson travelled to the Falls of the Schuylkil to dine early with Thomas Mifflin and his wife Sarah.

- Did the Committee on Style members confer with the members of their state delegation about their work?

Meeting date and the Society of the Cincinnati

What we know:

- The Society of the Cincinnati held triennial meetings. In 1784, Philadelphia was selected as the location of the national meeting in May of 1787.

- In 1786, the Annapolis Convention selected the date and location for the Constitutional Convention, to convene in Philadelphia in May of 1787.

- The literature of the Society of the Cincinnati recognized that the army had “lived in the strictest habits of amity through the various stages of war.”

What we don’t know:

- Was the timing and the location of the Constitutional Convention specifically chosen by Hamilton to align with the meeting of the Society of the Cincinnati?

- Did Hamilton purposely use the framers’ relationships and influence with the Society of the Cincinnati to promote ratification? How?

- Apart from its location as the situs of the Declaration of Independence, why else was Philadelphia chosen?

- Why meet in May, to overlap with the Society of the Cincinnati?

- Was the use of the phrase “spirit of amity” in the cover letter an intentional cross reference to the brotherhood of “amity” cultivated by the Society?

Prior cover letters

What we know: The Declaration of Independence and the Articles of Confederation each had cover letters. Thus, there was a tradition of using transmittal letters to the states/colonies for important political documents.

John Hancock signed the cover letter for Declaration of Independence. Interestingly, Morris drafted the reply from New York. The cover letter for the Articles of Confederation was dated November 17, 1777. The cover letter for the Articles was signed by Henry Laurens and Charles Thomson, the President and Secretary of the Continental Congress.

What we don’t know:

- How might the cover letter for the Declaration of Independence or the cover letter for the Articles of Confederation have influenced the drafting of the Constitution’s cover letter? Did the Committee have access to these prior cover letters in September of 1787?

- The process of adoption of the Articles of Confederation was delayed and otherwise problematic. Was the Committee purposely trying to avoid the the precedent of the Articles, which were proposed in 1777 but not finally ratified until 1781?

Delegates

What we know:

- Roger Sherman (Connecticut) was the only delegate to the Constitutional Convention who signed the Continental Association (1774), the Declaration of Independence (1776), the Articles of Confederation (1777) and the Constitution (1787).

- Five delegates signed the Constitution and the Articles of Confederation: John Dickinson (Delaware), Daniel Carroll (Maryland), Gouverneur Morris (New York and Pennsylvania), Roger Sherman (Connecticut) and Robert Morris (Pennsylvania).

What we don’t know:

- What information not reflected in Madison’s notes was shared by these delegates who attended prior conventions?

- What if any knowledge was shared about the role of the cover letter?

- What other discussions took place between delegates outside of the closed doors of Independence Hall during the summer of 1787?

Final copy of the cover letter

What we know:

- The final, executed copy of the cover letter has been lost to history. While it was published in newspapers around the country, the original version of the cover letter signed by Washington cannot be found.

- The final parchment copy of the Constitution was “engrossed” by Jacob Shallus, the calligrapher of the Constitutional Convention. Shallus’ final copy of the Constitution is on display at the National Archives.

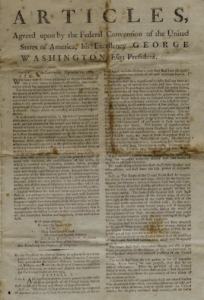

- Philadelphia printers Claypoole and Dunlap printed 500 copies of the Constitution (along with the cover letter and resolutions) for the delegates to distribute to Congress and their home states.

What we don’t know:

- What happened to the original copy of the cover letter signed by Washington? Was it kept by the printers?

- Did Shallus prepare an engrossed copy of the cover letter?

- Were there other working drafts, other than the handwritten “Morris draft” which was preserved in the records of the Constitutional Convention?

Washington’s circular letter to the states

What we know:

- June of 1783 Washington “wrote” a famous circular letter which was addressed to the governors of the thirteen states.

- The circular letter contained Washington’s longest public address during the war and set forth four objectives that he thought would be essential for the well being of the country.

- The famous circular letter was a model for Washington’s farewell address in 1796.

What we don’t know:

- Did Washington write his circular letter? Or did he have assistance from others, including Hamilton and/or Madison?

- A future post on Statutesandstories will explore similarities between Washington’s circular letter and the the Constitution’s cover letter.

- For example, did the same author use the phrase “ardently wish” in the circular letter and the phrase “most ardent wish” in the cover letter?

Hamilton’s lobbying efforts leading into the NY ratification convention

What we know:

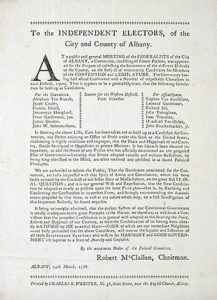

- In early 1788 copies of the Constitution were widely distributed in New York which prominently displayed the cover letter and Washington’s signature on top of the Constitution.

- The copies were printed between February 11 and March 21 by Claxton and Babcock in Albany, New York.

What we don’t know:

- Did Hamilton have any role in printing the “cover letter first” copies of the Constitution?

- Did Hamilton help the federalist committees across the state that cited to the cover letter in their campaign literature?

In 1787, Philadelphia was the nation’s largest city. Pictured above is the back of Independence Hall, which is approximately 5 blocks from Robert Morris’ house (pictured below) where Washington stayed during the summer of 1787. Other committee members lodged within easy walking distance of one another and Philadelphia’s famous taverns.

Miscellaneous

- Madison’s health deteriorated in August of 1787. How was his health from September 8 – 12?

- When did Morris finish work on the Constitution? Did he have time to write the cover letter?

- Pennsylvania delegate James Wilson read Ben Franklin’s famous “sun rising” speech to the Convention on September 17. Morris and Wilson, who were co-delegates from Pennsylvania, worked closely with Franklin during the Convention. Did Morris also help Franklin write the speech? When?

- James Wilson may have helped the Committee on Style. When and how?

- How did the voting for selection to the Committee on Style work? Did Washington lobby to put Hamilton on the Committee?

- We know the Committee consisted of strong nationalists. Was Hamilton elected to the Committee for the express purpose of drafting the cover letter?

- Did the Committee show Washington the draft before it was brought to the floor of the Convention on September 12?

- What can we infer from Washington’s schedule and diary? Washington’s diary reflects the following entry: “Tuesday 11th. In Convention. Dined at home in a large Company with Mr. Gardoqui. Drank Tea and spent the evening there.” Who was in the large company?

- Earlier in the week Washington dined at Mrs. Mary House’s boarding house on September 5. David Stewart in The Summer of 1787 surmises that Washington was conferring with Madison and other delegates who lodged there (located on the SW corner of Fifth and Market streets).

- Washington originally planned to lodge at Mrs. House’s establishment. Instead, he accepted Robert Morris’ invitation to stay at with the Morris family at their home located between 6th and Market Streets. This elegant Morris house would later serve as the executive mansion when Philadelphia was the nation’s capital from 1790 to 1800.

- While they were not related, Robert Morris and Gouverneur Morris were close associates who served as the Superintendent and assistant Superintendent of Finance under the Articles of Confederation. It is easy to imagine committee members consulting with Washington after hours.

- According to historian John Vile, Hamilton and Morris lodged at Miss Dailey’s boardinghouse on the north side of Market street between 3rd and 4th Streets. Rufus King stayed at the City Tavern. This fact raises interesting prospects of Hamilton and Morris working closely together during their committee assignment.

- Upon the conclusion of the Constitutional Convention, Major William Jackson, the Convention’s secretary, burned all loose scraps of paper. What papers did he destroy?

- Interestingly, on the last day of the Convention, Committee of Style member Rufus King “suggested that the Journals of the Convention should be either destroyed, or deposited in the custody of the President.” According to Madison’s notes, King explained that if made public, “a bad use would be made of them by those who would wish to prevent adoption of the Constitution.” Was it coincidental that Hamilton was concerned with confidentiality when the Convention began and King similarly sought to lock down Convention records on September 17? Does this fact provide support for the HAT premise that Hamilton wanted to suppress evidence of his authorship of the cover letter?

- Can plagiarism detection software be used to compare the cover letter’s text with known works by the Committee members to help verify the Hamilton authorship thesis?

- Madison outlived the other framers (including Hamilton who was famously killed in a duel in 1804). How should Madison’s letters 30 years later be compared with more contemporaneous sources?

- Would rigorous stylometric analysis support or refute the HAT?