The Hamilton Authorship Thesis

Recognizing the lion by his claw

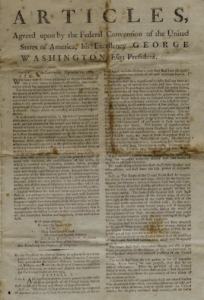

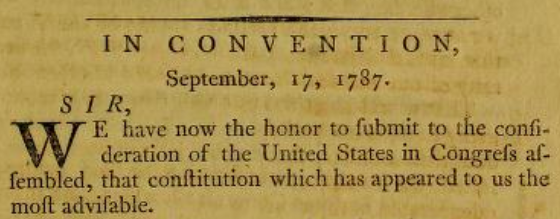

The Constitution was introduced to the world with a little known cover letter signed by George Washington, as the President of the Constitutional Convention. The cover letter “was read once throughout, and afterwards agreed to by paragraphs,” making it a unique official communication of the Constitutional Convention. But who wrote it?

For far too long, historians have assumed that the nearly forgotten cover letter was written by Gouverneur Morris, the so-called “penman of the Constitution.” Others have attributed the letter to Washington who signed it. This post will attempt to demonstrate that overwhelming evidence supports the conclusion that Alexander Hamilton was the author of the Constitution’s cover letter.

Hamilton was the only delegate from New York to sign the Constitution. He understood that ratification in New York faced an uphill battle. Indeed, the following year New York would only ratify the Constitution by a slim three vote margin. As argued below, portions of the cover letter were carefully drafted by Hamilton to respond to specific objections by his fellow New York delegates.

This post contends that Hamilton attempted to use the cover letter to leverage George Washington’s credibility and “universal popularity” in the campaign for ratification in New York. The original copy of the cover letter that was signed by Washington is lost to the world. Accordingly, we may never be able to assess the handwriting of the original document signed by Washington.

This may have been how Hamilton wanted it. Anticipating intense opposition in New York, Hamilton may have purposely suppressed evidence that he wrote the cover letter. Had Hamilton’s authorship of the cover letter been publicized, the cover letter would have been less valuable for the Federalists.

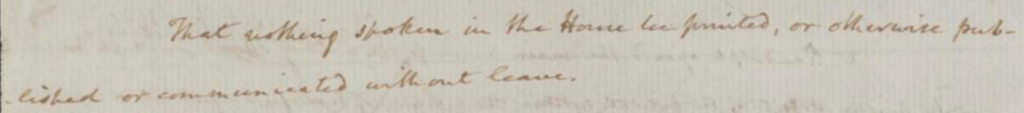

On the same day that Washington was unanimously selected to preside over the Constitutional Convention, he appointed Alexander Hamilton, George Wythe of Virginia and Charles Pinckney of South Carolina to the Committee on Standing Orders and Rules. Among the rules governing the Convention, the Committee required that delegates be sworn to secrecy to protect the sanctity of their deliberations.

No delegates to the Convention ever claimed authorship of the letter. Madison’s detailed notes of the Convention, which are silent on the letter’s authorship, were published posthumously in 1840. This secrecy and Hamilton’s tragic death in 1804 help explain why Hamilton’s identity as the author of the cover letter has remained a secret for so long.

The first post in this series, The Constitution’s Forgotten Cover Letter (Part I), provided background about the transmittal letter. Part 1 also introduced the “Hamilton Authorship Thesis” which proposes that Alexander Hamilton wrote the cover letter, but purposely kept his authorship a secret.

This post, Part II, makes the case that Hamilton’s unmistakable fingerprints are all over the cover letter. Using digitized primary sources on the National Archive’s founders.archives.gov website, it is possible to detect unmistakable Hamiltonian word combinations, patterns and his signature linguistic style. Doing so would have been unimaginable to prior generations of historians who simply lacked access to the 180,000 documents in this invaluable database.

The Hamilton Authorship Thesis (the “HAT Thesis”) asserts that Hamilton’s phraseology and linguistic fingerprints identified below are compelling proof that Gouverneur Morris did not write the cover letter. This post invites readers to fully engage with the inferential evidence of Hamilton’s authorship by exploring the cited primary sources, each of which is presented with its own link.

Separate and apart from the authorship question, some may conclude that the cover letter itself presents an equally fascinating story. What were the reasons why Hamilton would have wanted to draft the cover letter? What was the cover letter’s message? How did Hamilton intend to use it?

Part II asserts that Hamilton had in effect been “drafting” the cover letter for almost a decade. Several arguments in the cover letter originated in correspondence and newspaper columns that Hamilton began writing during the Revolutionary War. Thus, the origin of the cover letter converges with the story of Hamilton’s advocacy for a national government that could win the war and unify the nation.

The Hamilton Authorship Thesis explains that in the closing days of the Constitutional Convention Hamilton may have in fact volunteered to draft the cover letter. Moreover, the HAT Thesis explains why Gouverneur Morris and the other nationalists on the five-member Committee on Style would have wanted Hamilton to draft the cover letter for George Washington’s signature. George Washington may have expected as much.

Because the evidence is largely circumstantial, Part II is systematically organized the way that a prosecutor would build a case. Part II begins with an opening statement. Many, but not all of the witnesses pictured below are well known. They “testify” across the centuries through Hamilton’s correspondence, speeches and newspaper columns. It only makes sense then that Part II concludes with a closing argument and the jury instructions from Hamilton’s home state of New York.

Part III focuses on the importance of the cover letter. Historians have not fully explored the cover letter’s historic significance. The cover letter was cited by both the Federalists and Anti-Federalists during the intense ratification battle in 1788. The cover letter and its “spirit of amity” reemerged on the national scene in the 1830’s when the South Carolina’s Nullification Crisis threatened to tear the country apart. Not surprisingly it was also invoked in the years leading up to the Civil War.

Part IV raises as yet unanswered questions about the “forgotten” cover letter. Part IV also points out the need for additional research which would further validate (or could refute) the Hamilton Authorship Thesis.

Historical Record

Before attempting to prove Hamilton’s authorship of the cover letter, it makes sense to begin by surveying the documentary record left behind by the founders. Why have historians presumed that Gouverneur Morris wrote the cover letter? Only by understanding the limitations in the Constitutional Convention’s files can the weakness of the “conventional wisdom” be brought to light.

Although secrecy was maintained during their deliberations, the Convention’s Secretary, William Jackson, kept an official journal of the Constitutional Convention. When the Convention concluded on September 17, 1787, Jackson burned all loose scraps of paper and delivered the Convention’s journal and official records to George Washington for safekeeping. During his presidency, Washington turned the journal over to the Department of State. Click here for a concise summary of the records of the Convention.

For more than thirty years, the journal remained confidential. In 1819, the journal was finally printed pursuant to a joint declaration by Congress. Secretary of State John Quincy Adams oversaw and edited the publication at the request of President Monroe. Nevertheless, the Convention’s official journal is at best skeletal. It describes floor votes but does not discuss committee meetings. Click here for the Journal, Acts and Proceedings of the Convention, which quotes the cover letter without mentioning its authorship. In a footnote on page 367, John Quincy Adams merely mentions that the letter is copied from “paper deposited by President Washington at the Department of State.”

In the years after the journal’s publication, individual records by a handful of Convention delegates gradually became public. One of Hamilton’s co-delegates from New York, Robert Yates, kept daily notes. Based on a vocal disagreement over the Convention’s authority to replace the Articles of Confederation, Yates and the third New York delegate, John Lansing, departed the Convention on July 5th, well before the Convention concluded on September 17. In 1821, Yates’ incomplete notes along with the materials from Luther Martin were published as the Secret Proceedings and Debates of the Convention Assembled at Philadelphia, in the Year 1787, For the Purpose of Forming the Constitution of The United States of America.

The cover letter is quoted in the appendix of Yates’ Secret Proceedings, but again no suggestion is made as to its authorship. It is also noteworthy that both Yates and Martin were committed Anti-Federalists who opposed the Constitution and left the Convention early, before the cover letter was drafted. It is thus no surprise that neither Yates nor Matin shed light on the authorship of the cover letter.

James Madison outlived all of the other framers. Madison’s comprehensive daily notes were published posthumously in 1840. Click here for a link to Madison’s The Debates in the Federal Convention of 1787 Which Framed the Constitution of the United States of America.

Madison’s notes for September 8 describe that a committee was appointed by ballot “to revise the style of, and arrange, the articles which had been agreed to by the House.” On September 12, the Committee on Style reported back with its revised draft of the Constitution and the proposed cover letter. Madison’s notes are silent with regard to the authorship question. Thus, it is only through the framers correspondence and the drawing of inferences that the authorship question can be analyzed.

Between 1894 and 1905, the U.S. State Department published The Documentary History of the Constitution of the United States of America, 1786-1870, a five-volume work that attempted to compile all known records of the Constitutional Convention. Volume one of the Documentary History contains a draft of the cover letter, along with a handful of edits that were made by the Convention on September 12.

In 1911, Professor Max Farrand of Yale University prepared a multi-volume collection called The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787. Placing the records in chronological order, Farrand’s widely cited work aggregated the journal with Madison’s comprehensive notes and the individual notes taken by seven of the delegates (Yates, King, Mason, McHenry, Paterson, and Pierce). Farrand also included personal correspondence and other primary sources.

The following year Farrand published a one volume commentary, The Framing of the Constitution of the United States. Farrand observed that for over ten years he was engaged in the “wearisome” and often “mechanical” task of collecting and editing material. The problem remains that none of these records directly answers the question of authorship. Who “wrote” the cover letter?

In his well-respected work, Farrand describes that “while they were waiting for the report to be printed, the convention took up the document to accompany the constitution (the cover letter) and with some slight changes in wording approved it.” Farrand himself acknowledges, however, on page 183 that, “The draft of this (the cover letter) is in the handwriting of Gouverneur Morris and presumably was composed by him.” (emphasis added)

In other words, a four page hand written draft of the cover letter appears to be in Morris’ hand writing. By no means does this draft definitively resolve the authorship question. Since 1912, historians have routinely relied on this “presumption” by Farrand.

Yet, Farrand devotes but a single paragraph to his discussion of the letter. According to Farrand, the letter to Congress, “in general terms stated the problem before the convention and why it was necessary to develop a ‘different organization’ of government.”

In the preface to his work, Farrand readily admits on page viii that his 1912 narrative is “merely a sketch in outline.” “Nor is this intended to be a complete history,” Farrand warns, conceding that his seminal 1912 publication is merely a “brief presentation of the author’s personal interpretation of what took place in the federal convention.”

Without diminishing the importance of Farrand’s work, a single sentence in one paragraph of his voluminous scholarship set the stage for others to conclusively treat Morris as the author of the cover letter.

Historians universally recognize that Morris was the principal author of the September 12 draft of the Constitution. The strong evidence of Morris’ work on the text of the Constitution doesn’t support the conclusion that he also drafted the cover letter. In fact, the cover letter doesn’t align with the poetry or language of the preamble. This alone suggests that both documents had separate authors. The weak evidentiary support for Farrand’s “presumption” has effectively been overlooked by modern historians. Farrand would not have wanted scholarship on the letter to have ended in 1912.

What would Morris have to say?

Gouverneur Morris spoke more than any other delegate at the Constitutional Convention. Morris was neither quiet nor shy. In a letter to Thomas Pickering in 1814 Morris described his role in drafting the Constitution. According to Morris, “that Instrument was written by the Fingers which write this Letter.” Importantly, Morris was happy to claim credit for his central role preparing the Committee on Style’s September 12 draft. Morris, however, did not claim credit for the cover letter.

In a letter to Robert Walsh dated February 5, 1811, Morris recognized that the “framers” of our national Constitution “were not blind to its defects.” Morris described the cover letter as “their President’s letter of the seventeenth of September, 1787.” Interestingly, Morris does not hint that he had drafted the letter. Rather, the topic of his February 5 correspondence with Walsh was largely dedicated to a discussion of General Hamilton. It is thus noteworthy that Morris cited the “President’s letter” as part of a larger discussion about Hamilton.

In researching a biography about Morris, Harvard historian Jared Sparks wrote to James Madison. In a letter dated April 9, 1831, Madison (the only remaining framer still alive at the time) acknowledged Morris’ handiwork drafting the Constitution:

The finish given to the style and arrangement of the Constitution, fairly belongs to the pen of Mr. Morris; the task having, probably, been handed over to him by the Chairman of the Committee, himself a highly respectable member, and with the ready concurrence of the others. A better choice could not have been made, as the performance of the task proved.

Several observations flow from Madison’s description. First, the “style and arrangement” of the Constitution fairly belongs to Morris. Second, “the task” was probably “handed over to him” by the Committee’s Chairman, William Samuel Johnson. Madison thus suggests that Johnson gave out different tasks to different committee members, with the “ready concurrence” of other members. This begs the question, which task was assigned to Hamilton? Madison repeats that Morris performed the assigned (singular) “task” well, since a better choice could not have been made. Again, Madison makes no mention of the cover letter when discussing Morris’ task on the Committee.

A corollary to the “Hamilton Authorship Thesis” is the “Committee of Style Division of Labor Hypothesis,” which was presented for the first time in Part I of this blog.

Hamilton was absent from the Convention for almost all of July and August. Morris missed three weeks in late June, but still managed to speak more times than any other delegate at the Convention. The hypothesis proposes that five Committee members divided up the Committee’s work based on each member’s expertise as follows:

- Hamilton was charged with drafting the cover letter.

- Rufus King was responsible for drafting the two ratification resolutions.

- Morris, as we know, focused on the body of the Constitution and the preamble.

- Madison with his notes of the Convention in hand assisted all of the members (particularly Morris) to make sure that the Committee’s work did not run afoul of earlier votes; and

- Johnson, the Chairman and oldest member of the Committee, supervised the operation.

If the Committee members had been asked about the authorship of the cover letter (after the Constitution had been ratified), the HAT thesis asserts that they would have honestly answered as follows: Hamilton was the principal drafter of the cover letter. Hamilton understood the utility of the cover letter and the value of Washington’s signature to help secure ratification (particularly in New York). The Committee members would not deny that the letter was the work product of the entire Committee, the Convention at large, and its signatory, George Washington. There is also evidence that Pennsylvania delegate James Wilson may also have assisted the Committee. Nevertheless, the Hamilton Authorship Thesis asserts that it was primarily, if not exclusively, drafted by Hamilton.

Deconstruction of the Cover Letter

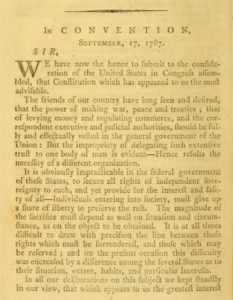

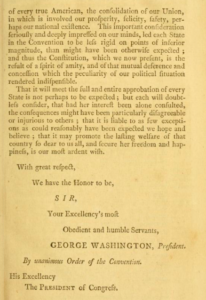

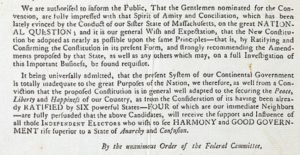

Pictured below is a printed copy of the cover letter for reference purposes. Only five paragraphs in length, the cover letter introduces the Constitution without attempting to summarize particular provisions. In her book Miracle at Philadelphia, historian Catherine Bowen describes the letter as “a most skillful and touching document which breathes confidence in what the Convention had achieved, makes no apologies but tells with seriousness and humility just what such a convention of diverse states felt it could and could not do.”

Pictured here is John Adams’ copy of the cover letter, which was printed along with the Acts of the First Congress

Historian Forrest McDonald, in his book Enough Wise Men: the Story of the Constitution, describes Morris’ draftsmanship of the Constitution as “brief, to the point, and clear.” Historians universally agree that the September 12 draft of the Constitution produced by the Committee on Style (largely drafted by Morris) was “succinct, polished, and written with grace and style.” But does this description by William Peters in “A More Perfect Union” apply to the cover letter?

Morris famously admitted authorship of “the Constitution” in his December 1814 letter to Pickering. Morris explained his objective was to reject “redundant and equivocal terms” thereby making the instrument “as clear as our language would permit.” Yet, this seemingly does not align with the style of the cover letter.

Describing Morris’ speeches at the Convention, Madison observed that the “correctness of his language and the distinctness of his enunciation were particularly favorable to a reporter.” Curiously, the cover letter fails to quote from the preamble. It also arguably lacks the stylistic features most commonly associated with Morris.

Upon careful reading, the cover letter might be described as verbose in places and even redundant? The word “interest” is repeated four times; “situation” repeats three times; and the words “safety,” “rights,” “magnitude,” “expected” and “most” are each repeated.

Several Hamilton biographers, including Ron Chernow, have noted that while his writing was brilliant, at times Hamilton could be “prolix.” The cover letter begins and ends with the superlative “most” (“most advisable” and “most ardent wish”). Several phrases in the letter could best be described as emphatic and wordy, not crisp or sharp:

- long seen and desired

- fully and effectually vested

- as to their situation, extent, habits, and particular interests

- prosperity, felicity, safety, perhaps our national existence

- seriously and deeply impressed on our minds

- mutual deference and concession

- particularly disagreeable or injurious to others

- we hope and believe

The cover letter touches on complex concepts ranging from checks and balances, federalism to social contract theory. In doing so, the cover letter appeals to both emotion and intellect. As will be discussed in Part III (pending) the use of the phrase “spirit of amity” may have been a subtle attempt to appeal to members of the Society of the Cincinnati. Click here for examples of Cincinnati publications and addresses which recognized that the army had “lived in the strictest habits of amity through the various stages of war.”

In only five paragraphs, the cover letter uses six semi-colons and two hyphenated sentences. Without attempting to engage in a full stylometric analysis, it is noteworthy that the average sentence is 62 words long (if the opening sentence is not counted). Click here for an example of a stylometric review of a recently discovered letter by historian Michael Newton. These characteristics, taken in their totality, might be compared to a Hamilton pamphlet or Publius’ work in the Federalist Papers.

Opening Argument for the Hamilton Authorship Thesis

The conventional wisdom wrongly assumes that Gouverneur Morris drafted the Constitution’s cover letter. Neither Madison’s notes nor the Convention’s official journal support authorship by Morris. And Morris never claimed that he drafted the cover letter. So, if Morris didn’t draft the cover letter, who did? How can the Hamilton Authorship Thesis be proven?

Washington and the members of the Committee on Style were well aware of Hamilton’s talents as a lawyer, pamphleteer and polemicist. They were also aware of the anticipated fierce resistance to the Constitution in New York. Hamilton was specifically elected to be a member of the Committee on Style. Yet he was absent for long portions of the Convention during July, August and early September. Thus, Hamilton wasn’t selected to be on the Committee due to his intimate familiarity with the debates that had taken place in his absence. Rather, he was selected for his longstanding support of a stronger federal government and the skill set that he brought to the committee.

As set forth below, there is compelling evidence that:

- Washington would have wanted Hamilton to draft the cover letter based on his proven talents and long history supporting federal power. Hamilton, more than anyone, was trusted to speak for Washington. Nobody else held the same pen or could channel Washington’s voice in the role that Hamilton played for decades;

- The members of the Committee on Style knew Hamilton well and were aware of his talents and relationship with Washington;

- Hamilton would readily have agreed to draft the letter to improve the chances of ratification in New York; and

- Hamilton’s fingerprints are in fact all over the letter.

A quick example is in order. In 1697, Isaac Newton anonymously submitted a solution to a scientific competition. Upon reviewing Newton’s solution, Jean Bernoulli is believed to have exclaimed, “tanquam ex ungue leonem” (we recognize the lion by his claw). During the Revolutionary War, Alexander Hamilton was known by the nickname the “Little Lion.” Hamilton’s authorship of the Constitution’s cover letter will similarly be discovered by the clues left behind by the lion.

Admittedly, the Hamilton Authorship Thesis rests on circumstantial evidence. Nevertheless, circumstantial evidence is routinely used in the courts. In many cases, circumstantial evidence is more reliable than eyewitness testimony.

In The Boscombe Valley Mystery by Sir Arthur Conan Coyle, Sherlock Holmes observed that:

“Circumstantial evidence is a very tricky thing,” answered Holmes thoughtfully. “It may seem to point very straight to one thing, but if you shift your own point of view a little, you may find it pointing in an equally uncompromising manner to something entirely different.”

This is not the case with the Constitution’s cover letter. The overwhelming weight of the evidence reveals Hamilton’s signature fingerprints. Hamilton not only had the opportunity to draft the letter as one of the five members on the Committee on Style, he also had the means and the motive.

As Alexander Hamilton lived in New York and the cover letter was sent to Congress in New York, it is only fitting to refer to the NY jury instructions. In a case involving circumstantial evidence, the judge will instruct the jury as follows:

The law draws no distinction between circumstantial evidence and direct evidence in terms of weight or importance. Either type of evidence may be enough to establish guilt beyond a reasonable doubt, depending on the facts of the case as the jury finds them to be.

Inferences from circumstantial evidence are required to be drawn as long as the inferences “flow naturally, reasonably, and logically from proven facts.” Similarly, Hamilton’s authorship of the cover letter will be proven by logical inferences that reasonably flow from the record described below.

1) Washington would have wanted Hamilton to draft the cover letter

Hamilton as the penman of the Army

During the Revolutionary War, one of George Washington’s most important and time consuming responsibilities involved directing the Continental forces both militarily and politically from his roving headquarters. This was largely done through written orders and correspondence to his officers, the Continental Congress, and the thirteen state legislatures.

Washington generated a tremendous volume of written correspondence when he led the Continental Army. According to historian Michael Newton, “[b]y the end of the war, some twelve thousand letters, orders, and reports, filling twenty-four volumes were written above Washington’s signature.” Alexander Hamilton: the Formative Years, Newton (2015). An additional 5,000 documents were written and signed by Washington’s aides in their own right. A large percentage of Washington’s correspondence was written by Alexander Hamilton.

“Problems of supply and organization plague every military commander, but they were particularly acute for General Washington because of a weak Congress and the recalcitrant states.” Washington and Hamilton: The Alliance That Forged America, Knott & Williams (2015). Before Hamilton joined his command staff, Washington observed in a letter to Joseph Reed in 1776 that “it is absolutely necessary therefore for me to have person’s that can think for me, as well as execute Orders.”

Washington found his indispensable aide-de-camp in the ambitious, brilliant and loyal Hamilton. Another of Washington’s aides, Robert Troup, famously said that, “[t]he pen for our army was held by Hamilton; and for dignity of manner, pith of matter, and elegance of style, General Washington’s letters are unrivaled in military annals.” According to historian John C. Fitzpatrick, “Hamilton undoubtedly was the finest penman of them all.” The Spirit of the Revolution (1924). With time, it became clear that Hamilton was assigned the task of drafting Washington’s most important correspondence.

The relationship between Hamilton and Washington

Beginning in early 1777, George Washington and his young aide-de-camp Alexander Hamilton developed a close and highly productive working relationship. Washington would later describe Hamilton as his “principal and most confidential aide.”

The close, strategic and personal relationship between Hamilton and Washington is explored by Naval War College Professor Steven F. Knott and historian Tony Williams in their book Washington and Hamilton: The Alliance That Forged America (2015). Knott and Williams recount that the relationship between Washington and Hamilton was “so close” that the general referred to Hamilton as “my boy.”

As described by Washington’s grandson, George Washington Parke Custis, when a dispatch arrived for Washington in the middle of the night:

there would be heard in the calm deep tones of that voice, so well remembered by the good and the brave in the old days of our country’s trial, the command of the Chief to his now watchful attendant, “Call Colonel Hamilton.”

Admittedly, many historians disagree as to the personal intimacy between Washington and Hamilton. Nevertheless, the record is clear that their professional working relationship elevated Hamilton into the unique status as Washington’s indispensable partner in war and peace for over two decades. (The preceding sentence combines the famous oration by Light Horse Henry Lee with the motto of the Alexander Hamilton Awareness Society.)

As described by Ron Chernow in his biography, Washington: A Life:

the two men were shaped by the same wartime experiences and shared the same basic concerns about the country’s political structure, especially the shortcomings of the Articles of Confederation and the need for a powerful central government that wold bind the states into a solid union, restore American credit, and create a more permanent army.

Despite a temporary falling out between the two in 1781, Hamilton and Washington reunited for the decisive Battle of Yorktown. Chernow explains that “[t]heir congruent political values lashed Washington and Hamilton together into a potent political partnership that would last until the end of Washington’s lifetime.” Once Hamilton rejoined Washington’s “military family” in 1781, the Washington-Hamilton strategic partnership would never fray again.

As late as 1798, the year before Washington’s death, Hamilton remained indispensable to Washington. Following the “XYZ affair” mounting hostilities with France resulted in the so called “Quasi War.” Since he had no military experience of his own, President Adams was forced to re-appoint Washington as Commander in Chief of the military. Due to his advanced age Washington had no intent to take the field unless actual hostilities broke out. Washington insisted that Hamilton be appointed second in command, at the rank of Major General. By doing so, Washington elevated Hamilton to serve as Inspector General, above all other officers who had served under Washington during the Revolutionary War. According to Ron Chernow, Hamilton’s appointment was a “precondition” for Washington.

The respect that Washington had for Hamilton was mutual. By way of example, in an anonymously written column in the New York Daily Advertiser on July 21, 1787 Hamilton refers to Washington as “[t]he late illustrious Commander in Chief.”

During the Convention the Pennsylvania Gazette reflected the excitement and good will in Philadelphia after Washington arrived on the scene. “In 1775, we beheld him at the had of the armies of America, arresting the progress of British tyranny. In the year 1787, we behold him at the head of a chosen band of patriots and heroes, arresting the progress of American anarchy, and taking the lead in laying a deep foundation for preserving that liberty by a good government, which he had acquired for his country by his sword.”

Preparing the population of New York for the approaching ratification battle, Hamilton explained that the states had it in their power:

in a special Convention, to avail themselves of the weight and abilities of men, who could not have been induced to accept an appointment to Congress; and whose aid, in a work of such magnitude, was on many accounts desirable. The late illustrious Commander in Chief stands foremost in this number.

It was no accident that Hamilton wrote this article for a New York audience during the summer of 1787. Hamilton was purposely invoking Washington’s prestige to lend credibility to the Convention and the as yet unfinished Constitution. Importantly, Hamilton knew that the pending Constitution was already being opposed by New York Governor Clinton.

In the book Original Meanings: Politics and Ideas in the Making of the Constitution, Jack Rakove explains that “[a]ppeals to the collective stature of the Convention and the prestige of Washington and Franklin” were an “important element of the Federalist [ratification] strategy.”

Given the close partnership between Washington and Hamilton, it is reasonable to propose that Washington would have wanted Hamilton to draft the Constitution’s cover letter for his signature. Hamilton, in turn, knew Washington’s reputation and credibility could be leveraged to help secure ratification of the Constitution. As set forth below, Hamilton would have wanted to draft the letter specifically for this purpose. Moreover, Hamilton had been advocating for a stronger federal government for years.

2) The members of the Committee on Style would have wanted Hamilton to draft the cover letter

A strong argument can be made that the other members of the Committee on Style would also have wanted Hamilton to draft the cover letter. According to Professor William Treanor:

In the years immediately preceding the convention, Johnson, Madison, King, Wilson, and Hamilton were in the Continental Congress, and Morris (who had earlier served in the Congress) was Assistant Superintendent of the Treasury. Thus, the group had working relationships that predated the convention.

Historian John Vile argues that the Convention made a conscious effort to use committees as a means of facilitating compromise. Committees reflected a balance between nationalists and supporters of states rights, along with a geographic balance between regions. In contrast, the Committee of Style was “to an astonishing degree,” nationalist in its orientation. In his book Novus Ordo Seclorum: The Intellectual Origins of the Constitution, historian Forrest McDonald categorized the fifty-five delegates at the Convention. Based on his analysis, 14 of the 55 delegates to the Convention were “strong nationalists”. Importantly, four of the five members of the Committee on Style fit this description (except for William Johnson who was a “moderate nationalist”). Professor Treanor further emphasizes that, “not only was the Committee on Style composed of nationalist voices, it was very precisely – composed of the leading nationalist voices at the convention.” And arguably, judging by his June 18 Convention speech, Hamilton was the most nationalist member of the entire Convention.

Of all the members on the Committee, Hamilton was closest with Gouverneur Morris both politically and socially. Eliza Hamilton claimed that Morris was Hamilton’s best friend. Morris was present when Hamilton died and gave his eulogy. Professor Treanor confirms that:

The closest tie on the committee, however, was between Morris and Hamilton. There was a natural bond between the two, outgoing, witty New Yorkers, both lawyers, both educated at Columbia, with similar politics and a common interest in finance. . . . The two had first worked together during the Revolutionary War when Hamilton was aide de camp to Washington and Morris a member of the Continental Congress inspecting the military. Hamilton revered the slightly older Morris for his intelligence and presence, and the two established a strong friendship. They worked closely together when Hamilton was in Congress and Morris the Assistant Superintendent of Finance.

Accordingly, all members of the Committee on Style knew Hamilton well. They were all nationalists. They had all previously worked together. They would have deferred to Hamilton or Washington’s wishes. They would also have understood the reasons why Hamilton would have wanted to draft the cover letter.

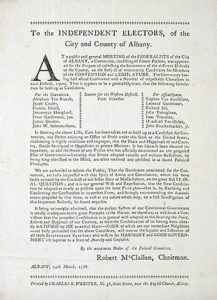

3) Due to anticipated resistance in New York, Hamilton would have wanted to draft the cover letter

Hamilton understood that the Constitution’s cover letter was not a mere formality. The only other delegates from New York, Yates and Lansing, made it clear that they opposed the Constitution when they departed the Philadelphia Convention in July of 1787. During his own absence from the Convention, Hamilton began the process of lobbying in favor of the Constitution. The Hamilton Authorship Thesis proposes that Hamilton appreciated more than anyone the importance of the cover letter. Hamilton knew that it was a necessary tool in the pending ratification campaign around the nation, but particularly in New York.

In his July 21, 1787 column in the Daily Advertiser, Hamilton attempted to counteract New York Governor Clinton’s growing hostility for the Philadelphia Convention. Hamilton wrote that:

It is currently reported and believed, that his Excellency Governor CLINTON has, in public company, without reserve, reprobated the appointment of the Convention, and predicted a mischievous issue of that measure. His observations are said to be to this effect:—That the present confederation is, in itself, equal to the purposes of the union: That the appointment of a Convention is calculated to impress the people with an idea of evils which do not exist: That if either nothing should be proposed by the Convention, or if what they should propose should not be agreed to, the one or the other would tend to beget despair in the public mind; and that, in all probability, the result of their deliberations, whatever it might be, would only serve to throw the community into confusion.

This column was written almost two months before the Constitution was signed on September 21. Hamilton nonetheless anticipated that Washington’s reputation and credibility could be leveraged to help secure ratification.

After the delegates departed Philadelphia for their home states Hamilton recorded several “conjectures about the new constitution.” Hamilton’s conjectures were never published, but it is suggested by the editors of Hamilton’s papers that the draft may have been intended as a newspaper article that Hamilton “put aside after beginning work on The Federalist papers.”

Assessing the strengths and weaknesses confronting the Constitution in the struggle for ratification, Hamilton wrote in his undated conjectures that “[t]he new constitution has in favour of its success these circumstances—a very great weight of influence of the persons who framed it, particularly in the universal popularity of General Washington.” Similarly, in a letter to Washington dated October 30, 1787, Gouverneur Morris acknowledged that it was difficult to tell whether the Constitution would be ratified. Yet, to Morris it was clear that the association between Washington’s name and the Constitution was of “infinite service.”

I have observed that your Name to the new Constitution has been of infinite Service. Indeed I am convinced that if you had not attended the Convention, and the same Paper had been handed out to the World, it would have met with a colder Reception, with fewer and weaker Advocates, and with more and more strenuous opponents. As it is, should the Idea prevail that you would not accept of the Presidency it would prove fatal in many Parts. Truth is, that your great and decided Superiority leads Men willingly to put you in a Place which will not add to your personal Dignity, nor raise you higher than you already stand: but they would not willingly put any other Person in the same Situation because they feel the Elevation of others as operating (by Comparison) the Degradation of themselves.

Indeed, since 1783 Hamilton had entertained the prospect of enlisting Washington to spearhead a campaign to help strengthen Congress. As the Revolutionary war was concluding, Hamilton wrote a congratulatory letter to Washington dated March 24, 1783 that provides insights into Hamilton’s thinking. Hamilton opined that there remained work to be done “to make our independence truly a blessing.” According to Hamilton, “[i]t now only remains to make solid establishments within to perpetuate our union.” Hamilton lamented, however, that this would be an arduous task as “the centrifugal is much stronger than the centripetal force in these states—the seeds of disunion much more numerous than those of union.”

In a follow-up letter to Washington dated September 30, 1783, Hamilton explained that he believed that “it might be in your power to contribute to the establishment of our Fœderal union upon a more solid basis.” When he wrote the March 1783 letter, Hamilton had hoped that:

Congress might have been induced to take a decisive ground—to inform their constituents of the imperfections of the present system and of the impossibility of conducting the public affairs with honor to themselves and advantage to the community with powers so disproportioned to their responsibility; and having done this in a full and forcible manner, adjourn the moment the definitive treaty was ratified.

Hamilton also explained that when Washington stepped down as commander in chief, “I wished you in a solemn manner to declare to the people your intended retreat from public concerns, your opinion of the present government and of the absolute necessity of a change.” In other words, in 1783 Hamilton wanted Washington’s voice to serve as the basis of a movement to reform the Articles of Confederation. Hamilton’s plans were premature, however, as Washington was desperate to return to civilian life at Mount Vernon.

Hamilton’s Convention Notes and the Objections from the New York Delegation

Fast forward to June of 1787. Hamilton was one of the most ardent nationalists in the country. He was convinced that replacement of the Articles of Confederation was absolutely necessary. The two other delegates on the three-member New York delegation disagreed. Robert Yates and John Lansing were selected for the New York delegation because of their vocal opposition to independent federal taxing authority. Thus, the New York delegation can appropriately be described as bipolar and schizophrenic. Ironically, the “chief catalyst for the convention” would be hamstrung by a hostile Governor and his anti-reform surrogates.

Hamilton’s son, John Church Hamilton, would later observe when drafting his father’s biography that New York sent to Philadelphia the “most prominent adversary and advocate for the union.” Ron Chernow observes that rather than leading a united delegation, “Hamilton was demoted to being a minority delegate from a dissenting state.” In the months leading up to the Convention, Madison assessed the state delegations that were being assembled. In a March 18, 1787 letter to Washington Madison accurately described Hamilton’s conundrum:

The deputation of N. York consists of Col. Hamilton, Judge Yates and a Mr Lansing. The two last are said to be pretty much linked to the antifederal party here, and are likely of course to be a clog on their colleague.

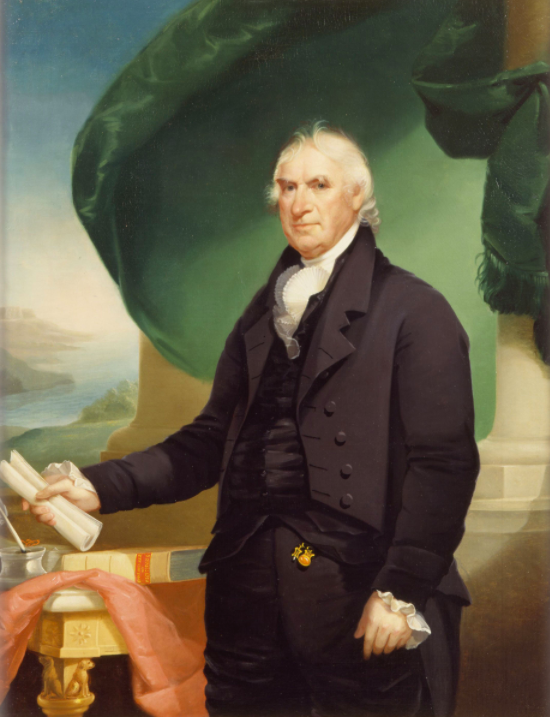

Madison’s description proved accurate. According to Robert Yates’ notes, on June 16, New York delegate John Lansing addressed the Convention and expressed his opposition to the Virginia plan. Lansing declared that the delegates should adhere to their instructions which were to “alter and amend” the Articles, not form a new “national government.” Lansing opined that “the states will never sacrifice their essential rights to a national government.” “New plans annihilating the rights of the states [state sovereignty] . . . can never be approved” except “upon evident necessity.” A portrait of Lansing is shown below. Click here for a link to the Trial of Levi Weeks, a murder case that Hamilton and Burr tried before Judge Lansing in the year 1800.

Madison’s notes further reveal the assertion by Lansing that, “it was unnecessary & improper to go farther” than the New Jersey Plan. According to Madison, Lansing elaborated that “N. York would never have concurred to sending deputies to the convention, if she had supposed the deliberations were to turn on a consolidation of the States and a National Government.” The cover letter directly responds to these arguments by claiming the “consolidation of the Union” was in the “greatest interest of every true American.” While delegates from other states would also leave the Convention for various reasons, Yates and Lansing were the first to leave on principle after the Great Compromise was proposed on July 5 to consolidate federal power and replace the Articles.

Alexander Hamilton also took notes at the Convention. Among other things, Hamilton recorded the following objections by Lansing : 1) The delegates only had “powers” to “revise the Confederation” and “New York would not have agreed to send members on this ground.” 2) The Convention should “preserve the state Sovereignties” as “Ind[ependent] States cannot be supposed to be willing to annihilate the States.” 3) “Legislatures cannot be expected to make such a sacrifice.“

Significantly, Hamilton’s notes of Lansing’s speech align with both Yates’ notes and with the arguments that would be made three months later in the cover letter. Accordingly, both Hamilton and Yates reflect the following objections by Lansing:

- The delegates were only empowered to alter and amend, not replace the Articles of Confederation. New York would not have agreed to send delegates if it apprehended that they would be forming a new national government.

- The state legislatures could not be expected to sacrifice their sovereignty; and

- New plans, annihilating the rights of the states, (unless upon evident necessity) would never be approved.

Hamilton would also address these points in his speech on June 18 and at the New York ratification convention. Central to the Hamilton Authorship Thesis (HAT) is the argument that Hamilton drafted the cover letter to assist in the New York ratification campaign. Part of the proof for the HAT thesis is the fact that these particular objections by Lansing are specifically addressed in the cover letter.

The cover letter will be discussed in detail in Part III (pending) and can be viewed with this link. Relevant parts of the cover letter and the alignment between the cover letter and Lansing’s objections are set forth below:

- To the extent that New York did not authorize its delegates to replace the Articles, the cover letter responded in part that “a different organization” was necessary. “In all our deliberations on this subject we kept steadily in our view, that which appears to us the greatest interest of every true American, the consolidation of our Union, in which is involved our prosperity, felicity, safety, perhaps our national existence.“

- With regard to Lansing’s objection that states wouldn’t sacrifice their sovereignty, the cover letter answered that “to secure all rights of independent sovereignty to each, and yet provide for the interest and safety of all — Individuals entering into society, must give up a share of liberty to preserve the rest.” The cover letter also explained that “the magnitude of the sacrifice must depend as well on situation and circumstance, as on the object to be obtained.”

- Responding to Lansing’s objection that the loss of state sovereignty should not be allowed except upon evident necessity, the cover letter asserted that a “different” form of government was a “necessity.” The cover letter appealed to the “spirit of amity and of that mutual deference and concession” which prevailed at the Convention and “was rendered indispensible” by “the peculiarity of our political situation.”

The Constitution’s cover letter is a relatively short document with only five paragraphs and 400 words. Yet, the cover letter directly addresses each of Lansing’s objections. Accordingly, this alignment between the cover letter, Lansing’s June 16 critique, Hamilton’s notes, and Hamilton’s speeches (on June 18 and at the New York ratification convention) provides meaningful clues as to the cover letter’s authorship

The themes of “necessity” and “sacrifice” can also be traced in the Federalist Papers. The word “necessity” is cited in 39 of the Federalist Papers by Hamilton (Federalist 1, 7, 8, 9, 11, 12, 13, 15, 16, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 59, 60, 65, 70, 72, 73, 75, 76, 77, 78, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85) and 6 of the Federalist Papers by Madison (Federalist 18, 19, 20, 51, 62, 63). The word “sacrifice” appears in 15 of Hamilton’s essays (Federalist 6, 15, 22, 30, 34, 35, 60, 61, 66, 68, 70, 72, 73, 75) and 3 of Madison’s essays (Federalist 57, 58, and 62).

The cover letter’s “spirit of amity” is also referenced in the Federalist papers. Hamilton refers to the “spirit of mutual amity and concord” in Federalist No. 6. Madison quotes the cover letter in Federalist 62 indicating that all hands acknowledged that the Constitution was the result “of a spirit of amity, and that mutual deference and concession which the peculiarity of our political situation rendered indispensable.”

Hamilton’s “delicate situation”

Hamilton gave his first speech to the Convention on June 18. He began his all day oration by explaining that he had remained silent thus far out of “respect for others” with “superior abilities, age and experience.” Hamilton also acknowledged his “delicate situation with respect to his own state.”

At the Convention states voted by delegation. Lansing and Yates, who were related by marriage, effectively controlled the New York delegation. Nonetheless, in the opening paragraph of his speech, Hamilton declared that he “could by no means accede” to the “sentiments” expressed “by his colleagues.”

In the very next sentence, Hamilton explained why:

The crisis however which now marked our affairs, was too serious to permit any scruples whatever to prevail over the duty imposed on every man to contribute his efforts for the public safety & happiness.

Under the Convention rules, delegates were not permitted to refer to each other directly by name. Nonetheless, Hamilton was referring to Lansing’s objections on June 16 (discussed above) when Hamilton referred to “the sentiments expressed by his colleagues.”

Hamilton explained that he did not support the New Jersey or the Virginia plans. “He was particularly opposed to that from N. Jersey, being fully convinced, that no amendment of the Confederation, leaving the States in possession of their Sovereignty could possibly answer the purpose.”

Next, Hamilton systematically replied to Lansing’s objections. This rebuttal by Hamilton is the core around which the cover letter is built.

He agreed moreover with the Honble gentleman from Va. (Mr. R.) that we owed it to our Country, to do on this emergency whatever we should deem essential to its happiness. The States sent us here to provide for the exigences of the Union. To rely on & propose any plan not adequate to these exigences, merely because it was not clearly within our powers, would be to sacrifice the means to the end.

At the end of his day long speech on June 18, Hamilton warns that “he sees the Union dissolving or already dissolved.” Addressing Lansing’s argument that the states would not agree to the proposed nationalist plan, Hamilton summarized that:

he sees that a great progress has been already made & is still going on in the public mind. He thinks therefore that the people will in time be unshackled from their prejudices; and whenever that happens, they will themselves not be satisfied at stopping where the plan of Mr. R. (the Virginia Plan) wd. place them, but be ready to go as far at least as he proposes.

Because the Yates and Madison notes are not exact transcripts, it is also useful to refer to Hamilton’s outline for his June 18 speech. Again, the same core concepts are repeated. These ideas that the current situation was in crisis, that it was necessary for our national existence to sacrifice state sovereignty, and that doing so would secure the freedom and happiness of our country. These themes flow from Lansing’s objections on June 16, to Hamilton’s rebuttal on June 18, to Hamilton’s notes, to the cover letter, and continue through the New York ratification debates.

Hamilton’s personal notes for his June 18 speech contain the following text, which is cross referenced with substantially similar text from the cover letter. The Hamilton Authorship Thesis posts that this overlap is not a coincidence:

- “Importance of the occasion“ (corresponds with the “present occasion” in the cover letter)

- “the public mind“ (corresponds with “deeply impressed on our minds” in the cover letter)

- “complete sovereignty” (corresponds with “independent sovereignty to each” in the cover letter)

- “The forming a new government to pervade the whole with decisive powers in short with complete sovereignty”; “power” (13x); “peace” (3x); “war” (5); “treaty” (2x); “money” (3x); “commerce” (4x) (correspond with “power of making war, peace, and treaties, that of levying money and regulating commerce”)

- Its “practicability to be examined”; “if not impracticable“ (corresponds with “it is obviously impracticable” in the cover letter)

- “local circumstances“ (corresponds with “situation and circumstance” in the cover letter)

- “Entrusts the great interests of the nation“ (corresponds with “the greatest interest of every true American” in the cover letter)

- “habitual sense of obligation” (corresponds with “habits” in the cover letter)

- “Particular & general interests“ (corresponds with “particular interests” in the cover letter)

- “necessity“ (corresponds with “necessity“)

- “necessary consequence“ (corresponds with “the consequences“)

- “powers too great must be given to a single branch”; “Entrusts the great interests of the nation to hands incapable of managing them” (corresponds with “the impropriety of delegating such extensive trust to one body of men is evident — Hence results the necessity of a different organization.”)

- “hopes and fears” (corresponds with “we hope and believe”)

- “will sacrifice” (corresponds with “the magnitude of the sacrifice”)

- “true interest and glory of the people“ (corresponds with “every true American“)

- “secure the union” (corresponds with “secure all rights”)

- “the objects of the general government; the means will not be equal to the object“ (corresponds with “the object to be obtained”)

- “Each principle ought to exist in full force, or it will not answer its end” (corresponds with “should be fully and effectually vested”)

- “the state must be well managed or the public prosperity must be the victim” (corresponds with “our prosperity“)

Interestingly, one theme from the cover letter is entirely absent in Hamilton’s speech. The cover letter concludes with the important message that the Constitution was “the result of a spirit of amity, and of that mutual deference and concession which the peculiarity of our political situation rendered indispensible.” The reason why this spirit of amity and compromise was not mentioned in Hamilton’s June 18 speech is obvious. The Connecticut Compromise was not reached until July 5. In other words, the spirit of amity and compromise had not yet materialized.

When it became clear that the Convention was moving in the direction of the Connecticut Compromise and an energetic federal government that would replace the Articles of Confederation, Lansing and Yates elected to depart the Convention. Or as Hamilton might write, “hence his delicate situation in New York.”

Similar overlap between the cover letter and Hamilton’s correspondence, newspaper columns, the Federalist Papers and Hamilton’s speeches at the New York ratification convention will be presented below in section 3 (Hamilton’s fingerprints). Rather than presenting the analysis in the text of this article, spreadsheets will be embedded to save space. Here is an example: Chart comparing June 18 speech with cover letter.

Given Hamilton’s delicate situation, one might ask, what became of the cover letter in New York? The journals of the New York Ratification Convention record that on the first day of the Convention the Constitution and the “letter accompanying the same to Congress” were read aloud. Thus, if the Hamilton Authorship Thesis is correct, Hamilton succeeded in concealing his authorship of the cover letter.

On July 1, 1788 at the New York Ratification Convention James Duane discussed “General Washington’s circular letter.” That same day, anti-federalist Melancton Smith replied to Duane’s arguments involving “the circular letter of the late commander-in-chief.” It is important, however, not to confuse the Constitution’s cover letter with Washington’s more famous June 8, 1783 “circular letter to the states.” Admittedly, I am guilty of making this mistake myself since both letters were “circulated” to the states.

In his 1783 circular letter, Washington shared his insights following the Revolutionary War. In many respects, the two letters are connected. As will be discussed in Part III (pending) the Constitution’s cover letter can be viewed as the continuation of the 1783 circular letter. The Commander in Chief would finalize his message to his beloved nation in his Farewell Address, which of course was co-written with Hamilton.

4) Hamilton’s fingerprints are all over the cover letter

Overview of methodology

Beginning with letters to James Duane in 1780 and Robert Morris in 1781, Hamilton began to lay out plans for a centralized federal government that could correct the defects with the Articles of Confederation. In his Continentalist essays in the early 1780s, Hamilton prophetically shared his views with the public at large. He wrote the report of the Annapolis Convention in 1786. After the Shay’s Rebellion, Hamilton led the charge to convene the Philadelphia Convention. Hamilton’s signature fingerprints on the cover letter can be traced back for almost a decade prior to the cover letter and are described below.

According to historian Catherine Drinker Bowen, Alexander Hamilton was “the most potent single influence toward calling the Convention of ’87.” Ron Chernow concludes his chapter on the Constitution with the observation that “Nobody would do more than Alexander Hamilton to infuse life into this parchment and make it the working mandate of the American government.” There are thus “thematic clues” that can be gathered from Hamilton’s life work. This also provides context to evaluate the voluminous “linguistic clues” that overwhelmingly connect Hamilton to the cover letter.

Before delving into the proof offered by the Hamilton Authorship Thesis it is useful to describe the different categories of evidence that will be presented. An overview of the contents of founders.archives.gov database is also in order.

What are the best kinds of circumstantial evidence in this case? Ideally, a skeptical observer should not be convinced merely by repeated words and phrases. The context of phrases is also important, along with the frequency that word combinations are used. Additionally, if a “Hamiltonian phrase” is used prior to September 17, 1787, the HAT Thesis believes that the phrase/word combination should be assigned more weight than phrases that were only used after the cover letter was written. Of course, the counter argument is that repeated phrases used after September 17, 1787 may reflect the author’s style and personality. And the author may purposely be quoting their own work. Yet, it is also important to recognize that a quotation to the letter after the fact doesn’t prove anything. For example, both Madison and Hamilton quote the cover letter in the Federalist Papers. Part III (pending) will demonstrate that the cover letter was routinely quoted during the ratification debates.

To make the point that the content and message of the cover letter should not be overlooked in this exercise, consider the following quote by delegate James Wilson. During the Pennsylvania ratification debates, Wilson stated that “[t]he letter which accompanies this constitution, must strike every person with the utmost force.”

Thus, readers are invited to look to the totality of circumstances when reviewing circumstantial evidence. Paraphrasing the letter itself, investigators should be aware of the “situation and circumstance” of any citation or “linguistic fingerprint.” This concept that the situation/circumstance is important is repeated three times in the cover letter.

The cover letter recognizes that, “It is at all times difficult to draw with precision the line between those rights which must be surrendered, and those which may be reserved; and on the present occasion this difficulty was encreased by a difference among the several states as to their situation, extent, habits, and particular interests.” The fourth paragraph of the cover letter concludes by declaring that the Constitution was the result of a “spirit of amity and mutual deference and concession which the peculiarity of our political situation rendered indispensible.”

The founders.archives.gov database contains 183,000 documents compiled and digitized by the National Archives and other researchers. Of these records, the largest share (32,116 representing 17.5%) were attributed to Washington. Yet, as described above, much of Washington’s war time correspondence was written by his aides. This is an example of how situation and context must be evaluated when reviewing database “hits.”

After Washington, the second most prolific writer in the database is Thomas Jefferson with 20,457 records. John Adams trails with 10,353 records. Fellow Committee on Style member, James Madison, wrote 8,509 records constituting 5% of the database. Hamilton comes in fourth place with 7,648 documents representing 4% of the database. With that said, Madison lived to the age of 85. Hamilton, depending on the date of his birth, was approximately 49 when he died. (Click here for a link to historian Michael E. Newton’s latest book, which casts new light on the date of Hamilton’s birth.) Thus, Madison had an extra 36 years to generate paperwork.

Unfortunately the other members of the Committee on Style are under-represented in the database as follows: Gouverneur Morris (240 records), Rufus King (289), William Samuel Johnson (less than 10). During the Covid-19 quarantine the University of Virginia provided access to its Rotunda.upress.virgina.edu database, which includes a digitized copy of Gouverneur Morris’ diary among other records. Of course, an author may (or may not) leave different “fingerprints” when writing in a diary, since a diary is a perfect example of context (Hamilton’s “situation and circumstance”) where the author is writing to an audience of one.

Readers are invited to refer to the founders.archives.gov database and run their own searches. Please note that comments from the editors and other footnotes should not be counted as “hits.” Likewise, when a letter is written from one founder to another (Jefferson to Madison, or Hamilton to Washington), it generates two hits. For purposes of consistency, this article strives to remove duplicate hits for the results displayed below. No effort to do so was attempted, however, when hundreds of hits were generated. Lastly, when identifying Washington hits, the cover letter was not counted in his total.

In a very real sense, Hamilton had been writing the cover letter for almost a decade, leaving dozens of clues behind which align with the cover letter. This linguistic evidence simply cannot be offered by any other founder who was on the Committee. Hamilton not only had the means, motive and opportunity, he left behind his signature fingerprints. Thus, Hamilton’s “thematic fingerprints” (ideas and concepts) date back to at least 1780. As will be demonstrated below, Hamilton’s “linguistic fingerprints” (word combinations and phrases) can be identified as far back as the Farmer Refuted essays in 1775.

Hamilton’s linguistic fingerprints

The HAT Thesis argues that the following word combinations and linguistic fingerprints are compelling evidence. While some may want to focus exclusively on the “forensics” of words and phrases (otherwise known as stylometry), the HAT Thesis asserts that the story of Hamilton’s authorship of the cover letter can be traced back to 1780, beginning with Hamilton’s letters to James Duane, Robert Morris, and Hamilton’s Continentalist essays. The story continues through the Annapolis Convention were Hamilton wrote the report calling for the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia. Each of these moments leaves clues behind, “thematic” fingerprints, along with signature “linguistic” fingerprints.

“seriously and deeply”

A good example of a Hamiltonian linguistic fingerprint can be found in Hamilton’s July 3, 1787 letter to Washington. Hamilton had departed the Convention and was writing to Washington to share his view that “this is the critical opportunity for establishing the prosperity of this country on a solid foundation.” At the end of the letter Hamilton writes that, “I am seriously and deeply distressed at the aspect of the Councils which prevailed when I left Philadelphia…”

The substantially similar phrase, “seriously and deeply impressed” appears in the cover letter. This signature Hamilton phrase is noteworthy for several reasons. First, both the cover letter and Hamilton’s July 3 letter use the expression “seriously and deeply” to express a critical concern. It is also noteworthy that the word “distressed” rhymes with “impressed” (suggesting that Hamilton liked the sound of the expression). Third, Hamilton’s July 3 letter precedes the cover letter by less than three months. Lastly, the expression “seriously and deeply” is not used by any other Committee on Style member in the entire founders.archives database.

The shortened phrase “deeply impressed” was repeatedly used by both Hamilton and Washington during their lives, including in correspondence between them (3/31/1783, 11/2/1796, 5/27/1798). Hamilton wrote into the Report of the Annapolis Convention that the delegates were “Deeply impressed however with the magnitude and importance of the object confided to them…” (If the words “magnitude” and “object” look familiar, this is because these terms are also used in the cover letter.) The founders.archives.gov database contains a total of 9 Hamilton hits using the phrase “deeply impressed”, including the Annapolis Report. Madison registers 3 hits which all occurred after the cover letter (in 1792, 1803 and 1830); Rufus King has 1 hit (in 1818), Gouverneur Morris has 1 hit (in 1790). By contrast, Washington generates 32 hits, including half a dozen during the war which may have been drafted by Hamilton.

“interest and safety”

The phrase “interest and safety” appears 37 times in the database. Of the five members on the Committee on Style, Hamilton uses the expression at least 8 times and “Washington” uses the expression 1 time (after Hamilton joined Washington’s military family). There are no records that James Madison, Gouverneur Morris, Rufus King or William Johnson used this phrase. Two additional examples where the expression was used are attributed to Washington’s Council of War on May 8 and 9, 1778. It is highly likely that Hamilton drafted these additional documents in 1778. In sum, it is safe to infer that Hamilton may have used the expression a total of 11 times, but there is no evidence that any other Committee member ever used this phrase.

The first time that Hamilton used the expression was in his Continentalist II essay on July 19, 1781. Hamilton used the phrase in the context of important common interests: “….and to transact many other important matters relative to the common interest and safety.” Similarly, in the cover letter the phrase is used in the same context: “secure all rights of independent sovereignty to each, and yet provide for the interest and safety of all.” Hamilton uses the phrase again in 1782, 1786 (the year before the Convention), 1789, 1792, 1793, and in his Explanation essays in 1795, and the Warning essays in 1797. Accordingly, this phrase is another good example of a signature Hamilton linguistic and thematic fingerprint, that was used prior to the cover letter and in the same context as the cover letter.

Interestingly, the word “interest” is used four times in the cover letter (“interest and safety,” “particular interest,” “greatest interest of every true American”, and “her interest”). To the extent that Gouverneur Morris has a reputation for being a tight and precise draftsman, one could argue that he would not have used the same word in the redundant fashion that it appears in the cover letter.

“our political situation”

The cover letter uses the word “situation” three times: the “situation” of the states; the magnitude of the sacrifice must depend on “situation and circumstances,” and when describing the peculiarity of “our political situation.” The expression “our political situation” is properly recognized as a signature Hamilton fingerprint, which he also used when writing for Washington. Unlike other Hamilton fingerprints which can be traced back prior to the Revolutionary War, Hamilton begins using this expression after the Constitution is written.

Hamilton first uses the phrase “our political situation” in Federalist No. 85 when he writes that “I am persuaded, that it is the best which our political situation, habits and opinions will admit, and superior to any the revolution has produced.” Thereafter, Hamilton repeats the phrase “our political situation” in a draft of Washington’s 4th Address to Congress in October of 1792, in his Defence of the Funding System in July of 1795, and 5 more documents through the year 1802.

The first example of Washington using the phrase is a July 4, 1789 letter to the Society of the Cincinnati (which may have been written by Hamilton), a letter to David Humphreys on March 16, 1791, and in the Fourth Annual Address to Congress written by Hamilton. The only other examples of a member of the Committee on Style using this phrase is Federalist No. 62 where Madison quotes the cover letter, and a September 22, 1792 article entitled A Candid State of Parties that Madison wrote for the National Gazette.

In sum, Hamilton used the expression “our political situation” 8 times beginning with Federalist 85. Madison used it two times beginning with Federalist 62 and Washington used it 4 times (several of which were likely written by Hamilton).

prosperity felicity safety perhaps our national existence

The cover letter contains the phrase “our prosperity, felicity, safety, perhaps our national existence.” The cover letter is the only instance where this eight word phrase appears in the founders.archives.gov database. Nevertheless, there are six examples of Hamilton using all eight words in the same document, including the Farmer Refuted essay in 1775, Federalist No. 15, Hamilton’s Report on the Mint, and his Examination essays. By contrast, there are no examples, of other Committee members using all eight words in the same letter.

The three words, prosperity, felicity, and safety generate eight Hamilton hits (dating back to 1775), two Madison hits (in 1815 and 1816), and no hits for the other Committee members. Interestingly, Washington has seven hits for these three words (but several of the examples may have been drafted by Hamilton).

“our union” and “the union” in the same letter

The two phrases “our union” and “the union” appear in different paragraphs in the cover letter. Starting with his September 3, 1780 letter to James Duane, Hamilton wrote that “[t]he idea of an uncontrolable sovereignty in each state…will defeat the other powers given to Congress, and make our union feeble and precarious.” This context aligns closely with the cover letter.

Hamilton was not the first to use the expression “our union.” The founders.archives.gov database contains examples of Benjamin Franklin and Adams using the expression in the early 1770s. Nonetheless, Hamilton was an early adopter who consistently used the phrase compared to other members of the Committee on Style. There are at least 9 examples of Hamilton using the phrase “our union.”

In addition to his 1780 letter to Duane, Hamilton also used the expression in letters to Robert Morris in 1781, John Laurence in 1782, and Washington in 1783. Hamilton repeatedly used the expression “our union” in speeches at the New York ratification convention in June of 1788, in Catullus essays, Philo Camillus essays, Examination essays, and the Farewell Address (portions of which were drafted by Madison, Washington and Hamilton).

Excluding letters written to his wife Elisa Hamilton, the database contains 12 examples of Hamilton using the phrase “our union.” In 8 of these examples, Hamilton also uses the phrase “the union” in the same document with “our union.” By comparison, there are 6 examples of Madison using these two phrases in the same letter (in 1786, 1791, 1799, 1812, 1815 and 1821); 3 examples of Washington using the two terms in 1790, 1791, and 1796 (the Farewell Address); 1 example of Rufus King using the two expressions in 1786, and no examples of Gouverneur Morris or William Johnson using the two expressions in the same letter.

hope and believe

For emphasis, the cover letter uses the expression “we hope and believe” in its last paragraph. This phrase generates only 6 hits in the entire database, including the cover letter. Hamilton used the phrase “we hope and believe” in a letter to his son Philip on December 5, 1791. There is no evidence that any other members of the Committee ever used this precise phrase. Hamilton also uses the phrase “I hope & believe” in a letter to Washington dated July 23, 1794.

Of course, the cover letter was speaking on behalf of the the Continental Congress and used the plural pronoun we. A search using the phrase “and believe” produces very interesting results.

The expression “hope and believe” places two verbs next to each other to emphasize that the writer/speaker not only hopes something to be true, but also believes it to be true. Another way of making a similar point is to write, “I trust and believe.” Hamilton uses the phrase “I trust and believe” twice in letters to Rufus King dated April 8, 1797 and James McHenry dated August 22, 1799. There is no evidence of any other Committee member using this phrase.

Hamilton also used the phrase “_____ and believe” with several other verb combinations:

- “it is currently reported and believed” in the Daily Advertiser on July 21, 1787.

- “extract and believe” in a September 14, 1779 letter to James Duane;

- “I always understood and believed” in a report to Congress regarding Baron von Steuben on March 29, 1790;

- “generally understood and believed” in the Defense No. XVI essay in September of 1795

No other Committee member uses this word combination as frequently as Hamilton. James Madison used the expression “He hoped and believed” only once in a speech to Congress on January 14, 1794 (but this may not be an exact transcription). Rufus King used the expression “here it is hoped and believed” once in a May 1, 1801 letter to Madison. There is no evidence that Gouverneur Morris or William Johnson used it at all. Morris preferred the expression “I do verily believe” (8/31/1790 letter to Robert Morris). Searches of the founders.archives database and the rotunda database reveal that the expression “verily believe” was a substantially more common expression that was used by all members of the Committee.

Washington, however, became a frequent user of the expression “hope and believe” after he signed the cover letter. Washington wrote to Jonathan Trumbull on June 8, 1788 that “I cannot avoid hoping, and believing, to use the fashionable phraze…” In a letter to Lewis Morris dated December 13, 1788 Washington wrote that “The prospect of national and individual prosperity, it is hoped and believed, is now more favorable than it hath hitherto been.” Washington also uses the phrase in letters dated 4/14/1790, 12/23/1793, and 1/22/1795. If the “verb and believe” combination is counted Washington used the expression a total of 8 times and Hamilton 9 times. By contrast, Madison used the “verb and believe” combination twice: in a debate in Congress on January 2, 1795 (“he expected and believed“) and in a letter dated May 1, 1830 (“as I understood and believe“).

In sum, the expression “hope and believe” (and similar verb “___ and believe” combinations) is a Hamilton fingerprint that he used contemporaneously at the time that the cover letter was written. This cannot be said for other Committee members. The fact that Washington’s correspondence also used this expression is also suggestive.

“union” near “existence”

The founders.archives.gov database allows searches of terms within ten words each other (using the “NEAR operator function”). Doing so with “union” near “existence” generates 10 Hamilton hits, 3 Madison hits and 1 Washington hit. The first Hamilton hit is an unsubmitted Resolution Calling for a Constitutional Convention that Hamilton prepared in 1783, a speech by Hamilton to the N.Y. Legislature in 1787, Hamilton’s July 21, 1787 column in the Daily Advertiser discussed above, Hamilton’s Conjectures about the Constitution following the Convention, Federalist Nos. 1, 21, 59, 80, Hamilton’s Catullus essays, and his Examination essays. There are no other examples from other Committee members in the database.

“general government” NEAR “of the union”

There are four examples of Alexander Hamilton using the two phrases “general government” near “of the union,” including in his July 21, 1787 column in the New York Daily Advertiser. Madison generates a single hit in 1788 and no other members of the Committee generate any hits.

Hamilton’s reasoning and argument style

In addition to words and phrases used by Hamilton, it is also possible to detect Hamilton’s reasoning, argument technique, and style. As discussed below, Hamilton used certain word combinations when making legal and rhetorical arguments. Several of the examples involve the use of the words, “it is evident”, “hence results”, reasonably “expected”, “the object”, and “magnitude.”

hence results evident necessity object magnitude

The words hence, results, evident, necessity, object and magnitude occur together in 20 documents created by Hamilton. This word selection only occurs in 2 documents created by Madison. No other members of the Committee generate a hit.

Both of the Madison hits occur subsequent to the cover letter (in 1800 and 1806). Two of the 20 Hamilton hits, the Farmer Refuted essay in 1775, and Hamilton’s letter to Morris on April 30, 1781, occur well before the cover letter. The 20 Hamilton hits also include Federalist 22 written in December of 1787, less than three months after the cover letter was written.

“reasonably have been expected”

The phrase “reasonably have been expected” generates 7 Hamilton hits out of 22 total occurrences in the database. Washington has 4 hits (which may have been drafted by Hamilton), Madison generates 2 hits (in 1804 and 1807), Rufus King produces 1 hit (in 1806). By contrast, the first Hamilton use of the phrase “reasonably have been expected” occurs in 1783, prior to the cover letter.

“hence” near “is evident”