The Legacy and Importance of the Constitution’s Cover Letter

The Constitution was introduced to the world by a “forgotten” cover letter signed by George Washington. The transmittal letter dated September 17, 1787 accompanied the Constitution on its trip from Philadelphia to New York, where Congress resided at the time. After the cover letter was read aloud and debated, Congress agreed to follow the procedure proposed by the Constitutional Convention. Copies of the Constitution – along with cover letter signed by Washington – were sent to the states to initiate the far from certain ratification process.

Ten months later on June 21, 1788, the Constitution became law. With a narrow vote of 57 – 47, New Hampshire became the ninth state to ratify the Constitution. After the Constitution crossed the required nine state ratification threshold, Virginia and New York quickly followed suit as it became clear that the experiment in democracy under the new Constitution would become a reality. President George Washington was sworn in as the first President the following year. The rest is history.

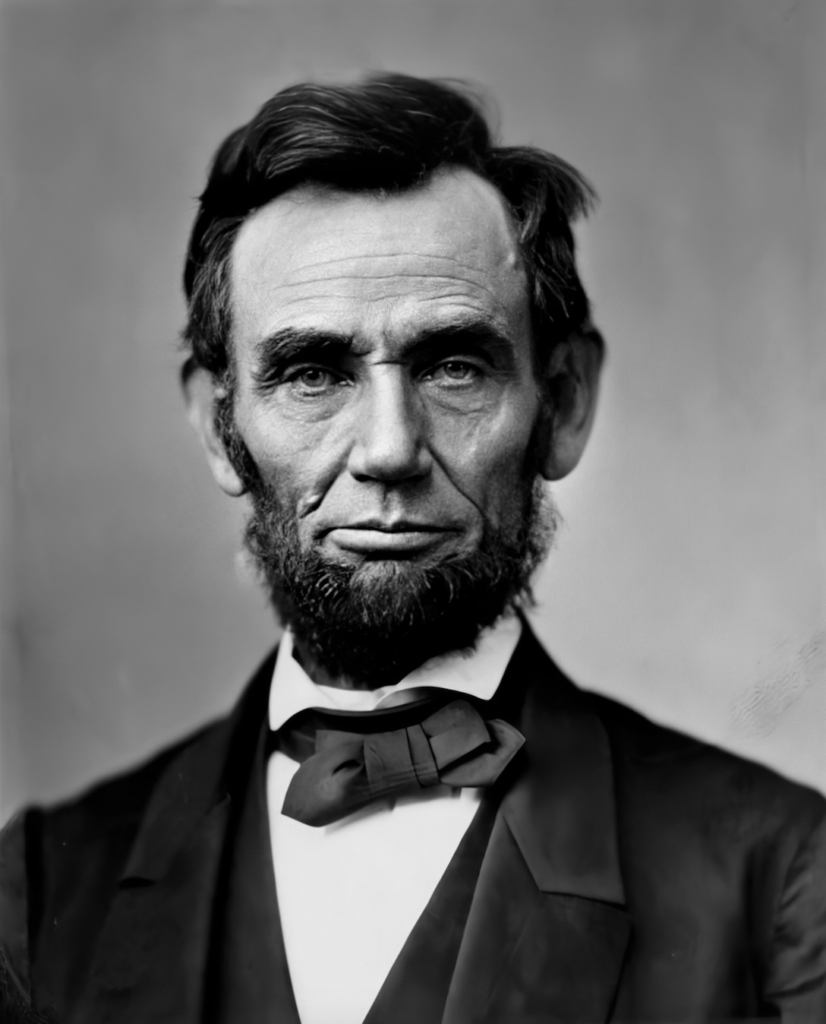

This post, Part III of a four-part series, explores the enduring legacy of the cover letter. As intended, the cover letter played an instrumental role initiating the national ratification debate. Yet, the cover letter’s message of national unity and compromise continued to resonate over the years, particularly during times of crisis. As described below, the letter’s “spirit of amity” and “mutual deference and concession” would be invoked by subsequent presidents, including Abraham Lincoln.

While the cover letter is largely unknown today, it was widely cited during the late 18th and 19th Centuries. President Washington himself quoted from the cover letter in a message to Congress during the highly partisan debate over Jay’s Treaty in 1796. Washington’s Attorney General, Edmund Randolph, cited the cover letter in 1791 as part of a legal opinion provided to President Washington involving the constitutionality of the Bank of the United States.

Not surprisingly the cover letter reemerged during sectional conflicts. The letter was cited during the nullification crisis in the early 1830s when President Jackson threatened to send troops into South Carolina. Abraham Lincoln quoted the cover letter to assail the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854.

Lincoln argued that Senator Douglas’ proposals were effectively repealing the Compromise of 1820 by allowing slavery to spread above the 36°30′ parallel. Lincoln would also cite to the letter during the Lincoln-Douglas debates. After he was elected President Lincoln invoked the cover letter in several presidential addresses. For the next century, a handful of presidents continued to cite to the cover letter, including Hayes, Cleveland and Truman.

Organization of this Post

Prior posts in this four-part series recount the cover letter’s extraordinary story. Part I provides background about the cover letter. Part II sets forth the Hamilton Authorship Thesis, which argues that Alexander Hamilton, not Gouverneur Morris was the cover letter’s author.

Part IV identifies as yet unanswered questions for further research. In so doing, Part IV invites a national discussion to uncover remaining secrets of the cover letter’s narrative. Arguably, the questions in Part IV involve one of the most intriguing unsolved mysteries in the early history of our republic.

Given the volume of material recently uncovered about the cover letter, this post is divided into six sections. Section 1 (What’s in a Name?) describes how the cover letter has never been assigned a single label. This ambiguity over who wrote the letter, what to call it, and the absence of the executed copy signed by Washington may help explain why the letter is largely unknown to the general public. Section 2 (Scholarly Commentary on the Cover Letter) quotes from leading scholars of the ratification period who emphasize the extraordinary importance of the cover letter in shaping the ratification debate from 1787-1788. Section 2 also introduces the multi-volume Documentary History of the Ratification of the Constitution which provides many of the primary sources discussed in this post.

Section 3 (The Cover Letter during Ratification) explores how the cover letter was widely disseminated, quoted, and used by the Federalists during the ratification debates. Section 4 (The Cover Letter over time) provides examples of how the cover letter and its “spirit of amity” and compromise were subsequently employed by elected officials, particularly during times of crisis in American history.

Section 5 (Abraham Lincoln and the Constitution’s Cover Letter) focuses on four speeches by Abraham Lincoln, prior to and during the Civil War. In each case, Lincoln was reaching back to the founding generation in an effort to reach compromise consistent with the rule of law.

Section 6 (Publications containing the Cover Letter) provides links and a discussion of early publications that commonly printed the cover letter during early periods.

1. What’s in a Name?

Although it was widely published alongside the Constitution, the founding generation never agreed on a single “label” for the cover letter. Perhaps the lack of an agreed title (and the ambiguity surrounding its authorship) is one of the reasons that the cover letter has been largely forgotten.

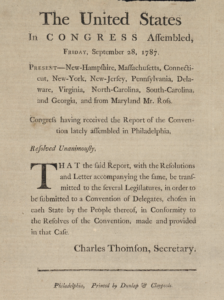

On September 28, 1787 Congress unanimously voted to send the “Report of the Convention lately assembled in Philadelphia” to the states for ratification. In the Congressional Resolution pictured below, the Constitution’s cover letter is described merely as “the Letter accompanying the same.” Click here for a link to the Congressional Resolution at the Library of Congress.

In 1787 and 1788 the cover letter was read aloud at several state ratification conventions. For example, the journal of the New York Ratification Convention in Poughkeepsie reflects that on June 18, 1788 the Constitution was read “together with the resolutions and letter accompanying the same to Congress…”

At the Georgia Ratification Convention, the cover letter was known as the “annexed letter.” The records of the Georgia Convention reflect that the “proposed Federal Constitution, together with the annexed letter and resolutions; the resolution of Congress, and those of the legislature of this state” were received and read.

Thomas McKean, the Chief Justice of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, described the cover letter as the “excellent letter which accompanies the proposed system…” At the Pennsylvania Ratification Convention on November 28, 1787, Judge McKean suggested that the delegates carefully read the letter:

The excellent letter which accompanies the proposed system will furnish a useful lesson upon this occasion. It deserves to be read with attention and considered with candor. Allow me therefore, sir, to close the trouble which I have given you in discussing the merits of the plan with a perusal of this letter-in the second paragraph of which the reason is assigned for deviating from a single body for the federal government.

James Wilson was a leading delegate at the Constitutional Convention who also spoke at length during the Pennsylvania Ratification Convention. On December 4, 1787 Wilson argued that while the imperfect Constitution was perhaps “not such as was expected,” nevertheless “it may be BETTER” than the Articles of Confederation. Wilson proceeded to quote from the cover letter, stating that the “letter which accompanies this Constitution, must strike every person with the utmost force.”

South Carolina delegate Charle Cotesworth Pinckney referred to the cover letter as “the Letter from the Convention to Congress.” Shortly after the Philadelphia Convention concluded, Pinckney wrote to Matthew Ridley on September 29, 1787 that:

I do not suppose it will meet your entire approbation, but when you consider the different Interests & Habits of the several States and that this plan of government was the result of mutual concession and Amity, it will account for the introduction of some clauses that may appear to you exceptionable. You should read the Letter from the Convention to Congress before you read the Constitution, as we have there briefly stated our reasons for having made it such as it is.

In an essay published in the Maryland Journal on March 25, 1788, the cover letter was referred to as “the circular letter accompanying the proposed plan.” Otho Holland Williams, writing under the pseudonym “A Marylander” suggested that “the letter speaks best for itself and ought to be published, as a general defence of the Constitution, in every Paper that contains an argument against it.”

In 1804, Chief Justice John Marshall published a multi-volume biography of George Washington. Interestingly, when quoting from the cover letter Marshall merely described it as “a letter subscribed by the president.” James Madison quoted the letter in Federalist 62, but neglected to attribute what he was quoting. In an 1824 letter to Henry Lee, Madison referred to the cover letter as “the address of the Convention prefixed to the Constitution.”

Gouverneur Morris quoted the cover letter in 1811, but was silent as to authorship. Click here for a link to Morris’ February 5, 1811 letter to Robert Walsh. Referring to the “framers,” Morris described the cover letter as “their President’s letter of the seventeenth of September, 1787.” The Hamilton Authorship Thesis suggests that this description by Morris is evidence that Morris did not write the letter.

In the 1833 treatise on constitutional law, Supreme Court Justice Joseph Story referred to the cover letter as the “Letter of the Convention, 17th Sept. 1787.” Click here for a link to 3 Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States 490.

2. Scholarly Commentary on the Cover Letter

Scholars of the ratification period have documented the central role of the cover letter during ratification. In particular, John Kaminski and his colleagues at the Center for the Study of the American Constitution (CSAC) recount that “[t]he importance of Washington’s letter of 17 September 1787 as president of the Convention to the president of Congress cannot be over emphasized.” Click here for a discussion of George Washington and the cover letter on the CSAC’s website.

In the book George Washington: the Man of the Age, Kaminski describes Federalist messaging following the Philadelphia Convention:

Although Washington, as much as possible, refrained from public participation in the debate over ratifying the Constitution, this letter under Washington’s signature was printed repeatedly along with the new Constitution throughout the country in newspapers, broadsides, pamphlets, magazines, and almanacs. It was also frequently quoted in Federalist essays defending the Constitution. The letter strongly supported a powerful argument made by those who supported the Constitution: “If Washington supports the Constitution, who are you to oppose it?” It was a difficult question to answer.

In his analysis of the rhetoric following the Constitutional Convention, William Riker attempted to quantify the most influential publications of the period. According to Riker, Washington’s endorsement of the Constitution was “one of the most widely used Federalist arguments” which the Federalists employed “immediately and extensively.” The Strategy of Rhetoric: Campaigning for the American Constitution.

Using the early volumes of the CSAC’s Documentary History of the Ratification of the Constitution (DHRC), Riker determined that the cover letter was cited at least 76 times during this period. It is clear, however, that Riker’s analysis necessarily undercounts citations to the cover letter. Riker did not have access to the completed 34 volume set of the DHRC when he passed in 1993.

According to Riker, the cover letter was the “first statement of what became typical Federalist arguments on the inadequacy of the Articles, on the consequent necessity of Union and consolidation, and on the desirability of ratification.” Riker suggested that the cover letter’s “strongest” argument may have been the statement that “the greatest interest of every true American” was “the consolidation of our Union, in which is involved our prosperity, felicity, safety, perhaps our national existence.”

Another Federalist argument supporting ratification was the prominence of Washington, Franklin and the other respected members of the Philadelphia Convention. In the Pulitzer Prize winning book Original Meanings: Politics and Ideas in the Making of the Constitution, Jack Rakove explains that “[a]ppeals to the collective stature of the Convention and the prestige of Washington and Franklin” were an “important element of the Federalist [ratification] strategy.” Not surprisingly, when the cover letter was printed in Federalist newspapers it prominently featured Washington’ signature in large, bold type.

The cover letter’s “spirit of amity” and compromise was another critical message echoed in the debates. As described by Ron Chernow, “Washington wisely made an understated case for approval, noting the conciliatory spirit that had led to its passage.” Washington: A Life. As set forth below, ultimately the framer’s spirt of “mutual deference and concession” may be of more lasting importance than any of the other political arguments in the cover letter.

Peter Knupfer focuses on the importance of compromise in civil society under a federal union. In his book, The Union As It Is, Constitutional Unionism and Sectional Compromise, Knupfer discusses the lesson of compromise and conciliation in our national political culture, which was central to the cover letter. For Knupfer, the Constitutional Convention had “found a way out of pluralism’s maze; compromise had created unity in diversity.” Kunpfer writes that during the ratification struggle the Federalists praised the “Convention’s unprecedented ability to resolve conflict while they simultaneously described the Constitution as the imperfect product of compromise.”

The New Hampshire newspaper, Freeman’s Oracle, contains the following passage by Probus (not to be confused with Publius) citing all three Federalist arguments mentioned above: (i) recognition of the Convention’s spirt of amity and compromise, (ii) deference to the “first characters” who drafted the Constitution, and (iii) an an appeal to the national interest. The article was addressed to the Electors of New Hampshire and appeared in Freeman’s Oracle on December 22, 1787:

[The framers were] chosen from among the first characters in the country. They have been convened—and perhaps an equal degree of Genius, Wisdom and public Virtue was never found in the same number of men, collected for any governmental purpose, since the birth of civil society, as appear’d in this convention.—They enter’d upon and conducted their important deliberations “with that spirit of amity, and of mutual deference and concession” which was indispensably necessary, where there was such a variety of local interests, prejudices and habits to be consulted. The result of these deliberations—deliberations which had for their object a matter of as great magnitude and importance as ever was submitted to the discussion of a free people—is now before the public. The only question to be determined is whether the federal constitution now submitted to us is calculated to promote and secure the liberties and happiness of the United States or not.

Daniel Farber mines the cover letter for evidence of the founder’s intent, as relates to modern debates about federalism. While Farber is focused on questions of constitutional construction, he provides meaningful commentary on the “unique” status of the cover letter. Farber observes that the cover letter is “free from the problems of reliability or typicality that plague the record of the debates of the Philadelphia and ratification conventions” because it is the only “official” explanation unanimously approved by the Convention. Click here for a link to Farber’s law review article, The Constitution’s Forgotten Cover Letter: An Essay on the New Federalism and the Original Understanding.

As for the cover letter’s enduring message, Peter Knupfer recognized that the founder’s accomplishments in 1787 provide a model for civic discourse today. “The convention’s triumph over deep-seated conflicts of sections, interests, and interpretations of republican ideals became an object lesson in civic conduct, a model for citizen and politician.”

Shortly after the Constitution was signed, the essayist, Curtius, heralded that Americans should “behold the greatest concessions made by the strongest; and, if any partiality is shown, it is in favor of the weak.” For Curtius it was admirable that the delegates exercised moderation in “making the most generous concessions to each other for the common welfare, and directing their deliberations with the most perfect unanimity.” The Curtius I essay which appeared in the New York Daily Advertiser on September 29, 1787.

Pennsylvania delegate James Wilson argued in a famous speech in Philadelphia that the spirit of amity found in the Constitution “ought rather to command a generous applause, than to excite jealousy and reproach”:

But I will confess that in the organization of this body a compromise between contending interests is descernible; and when we reflect how various are the laws commerce, habits, population and extent of the confederated States, this evidence of mutual concession and accommodation ought rather to command a generous applause, than to excite jealousy and reproach. For my part, my admiration can only be equalled by my astonishment in beholding so perfect a system formed from such heterogeneous materials.

Wilson’s October 6, 1787 “Speech at a Public Meeting” in Philadelphia was reprinted in dozens of newspapers across the nation. Washington would appoint Wilson to the Supreme Court the following year.

3. The Cover Letter during Ratification

As illustrated above, the cover letter was frequently cited during the ratification debates. It was commonly cited in the newspapers, as the thirteen states studied the pros and cons of the newly proposed Constitution.

The New York Daily Advertiser was one of the first papers to publish original commentary about the Constitution. An essay appearing on September 24, 1787 congratulated the “National Convention” and opined that reform was “indispensably necessary.” The unsigned article entitled “A revolution effected by good sense and deliberation” contained the following discussion, quoting from the cover letter:

If the New Constitution is not as perfect in every part as it might have been. . . let it be remembered, that “the mutual deference and concession,” and that “spirit of amity” from which this Constitution has resulted, ought to have a strong operation on the minds of all generous Americans, and have due influence with every State convention, when they come to deliberate upon its adoption.

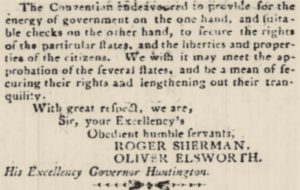

Upon departing the Constitutional Convention, Connecticut delegates Roger Sherman and Oliver Elsworth wrote a transmittal letter of their own to Connecticut Governor Huntington, summarizing their support for the Constitution. The Connecticut cover letter refers to the Constitution’s cover letter as the Convention’s “letter addressed to Congress” setting forth the “general principles which governed the Convention in their deliberations” in Philadelphia. Copied below are excerpts of Sherman and Elsworth’s letter, as reprinted in the Philadelphia Packet newspaper on November 10, 1787.

One of the most famous speeches of the period that gained national attention was James Wilson’s “Speech at a Public Meeting” in Philadelphia on October 6, 1787. Wilson conceded that the Constitution was not perfect, but ultimately asserted that it was the “best form of government which has ever been offered to the world.” Pictured below is a copy of the speech appearing in the Independent Gazetteer on October 11, 1787.

While not referring to the Constitution’s cover letter per se, Wilson tapped into the spirit of compromise reflected in the letter:

But I will confess that in the organization of this body, a compromise between contending interests is discernible; and when we reflect how various are the laws, commerce, habits, population, and extent of the confederated states, this evidence of mutual concession and accommodation ought rather to command a generous applause, than to excite jealousy and reproach. For my part, my admiration can only be equalled by my astonishment, in beholding so perfect a system, formed from such heterogeneous materials.

While not as famous at the Federalist Papers, Connecticut delegate Oliver Ellsworth wrote thirteen essays using the pseudonym A Landholder. In the Landholder VII essay printed on December 17, 1787 in the Connecticut Currant, Ellsworth quotes extensively from the cover letter:

I have often admired the spirit of candour, liberality, and justice, with which the Convention began and completed the important object of their mission. “In all our deliberations on this subject,” say they, “we kept steadily in our view, that which appears to us the greatest interest of every true American, the consolidation of our union, in which is involved our prosperity, felicity, safety, perhaps our national existence. This important consideration, seriously and deeply impressed on our minds, led each state in the Convention to be less rigid on points of inferior magnitude, than might otherwise have been expected; and thus the Constitution which we now present, is the result of a spirit of amity, and of that mutual deference and concession, which the peculiarity of our political situation rendered indispensable.”

Let us, my fellow citizens, take up this constitution with the same spirit of candour and liberality; consider it in all its parts; consider the important and advantages which may be derived from it, and the fatal consequences which will probably follow from rejecting it.

William R. Davie, a delegate to the Constitutional Convention and the North Carolina Ratification Convention, also quoted from the letter. On July 24, 1788 at the North Carolina Ratification Convention he praised “laudable” the “spirit of amity” in Philadelphia which he hoped would also govern the North Carolina Convention:

Mutual concessions were necessary to come to any concurrence. A plan that would promote the exclusive interests of a few states would be injurious to others. Had each state obstinately insisted on the security of its particular local advantages , we should never have come to a conclusion. Each, therefore, amicably and wisely relinquished its particular views. The Federal Convention have told you, that the Constitution which they formed “was the result of a spirit of amity, and of that mutual deference and concession which the peculiarity of their political station rendered indispensable.” I hope the same laudable spirit will govern this Convention in their decision on this important question.

George Washington avoided directly participating in the ratification debates. Nevertheless, it is clear that he closely monitored the news. In a letter to Sir Edward Newenham, Washington described that “a greater Drama is now acting on this Theatre than has heretofore been brought on the American Stage, or any other in the World.” Washington must have been proud to observe that “[w]e exhibit at present the novel & astonishing Spectacle of a whole People deliberating calmly on what form of government will be most conducive to their happiness. . .”

In his letter to Newenham, Washington did not cite the cover letter by name, but summarized the message of the cover letter:

Although there were some few things in the Constitution recommended by the Fœderal Convention to the determination of the People, which did not fully accord with my wishes; yet, having taken every circumstance seriously into consideration, I was convinced it approached nearer to perfection than any government hitherto instituted among men. I was also convinced, that nothing but a genuine spirit of amity & accomodation could have induced the members to make those mutual concessions & to sacrafice (at the shrine of enlightened liberty) those local prejudices, which seemed to oppose an insurmountable barrier, to prevent them from harmonising in any system whatsoever.

4. The Cover Letter over time

After ratification, the cover letter was recognized as an important foundational document in our national canon. It was first cited as an authority during the Washington administration. It would continue to inform the national discourse for many years until it fell off our national radar in the later decades of the 20th Century. The discussion below surveys examples of how the cover letter was invoked over time.

In 1791, Attorney General Edmund Randolph cited the cover letter in a legal opinion to George Washington. Randolph used the cover letter during a disagreement within the cabinet over the constitutionality of the Bank of the United States. Ironically, if the Hamilton Authorship Thesis is correct, Randolph would have been citing “Hamilton” against Hamilton:

Whosover will attentively inspect the Constitution, will readily perceive the force of what is expressed in the letter of the convention; “That the Constitution was the result of a spirit of amity, and mutual deference & concession.” To argue, then, from its Style or arrangement, as being logically exact, is perhaps a scheme of reasoning not absolutely precise.

In 1796, at the end of his second term, Washington cited the cover letter in a written message to Congress. While Washington, Hamilton and other Federalists supported the controversial Jay’s Treaty, Congressional opposition from the emerging Jeffersonian Democratic-Republican party was intense. Click here for a discussion of Jay’s Treaty, which was narrowly approved in the Senate but was almost defunded in the House by James Madison. In his March 30, 1796 message to the House Washington wrote:

It is a fact declared by the General Convention, and universally understood, that the constitution of the United States was the result of a spirit of amity and mutual concession. And it is well known, that under this influence, the smaller States were admitted to an equal representation in the Senate, with the larger States; and that this branch of the government was invested with great powers: for, on the equal participation of those powers, the sovereignty and political safety of the smaller States were deemed essentially to depend.

President Jefferson’s election in the year 1800 represented the first peaceful transition of power from one party to another in American history. Click here for a discusion of the election, otherwise known as the Revolution of 1800. After the election was thrown into the House of Representaives following an electoral college deadlock beween Jefferson and Burr, state militias were put on standby in at least two states. Not surprisingly, the spirt of the cover letter would be called upon that year.

Copied below is an essay by Tench Coxe writing under the pseudomyn “A Constitutionalist.” Known to his political rivals as “Mr. Facing Bothways”, Coxe was previously a Federalist who later supported Jefferson’s Democratic-Republican party and was appointed purveyor of pubic supplies in the Jefferson and Madison administrations:

In the 1830’s President Jackson and South Carolina came perillously close to military confrontation during the Nullification Crisis of 1832-1833. The controversy centered around the so called Tarrif of Abominations, which was bitterly opposed by southen states led by Vice President John Calhoun. Click here for a discussion of the the Nullification Crisis and the Force Act of 1833.

The crisis was resolved after Congress passed the Force Act, which authorized Jackson to use the military to collect unpaid tariffs. At the same time, Congress offered a compromsie by lowering tariff rates. South Carolina, in turn, reciprocated by rescinding its nullification ordinance. It is thus no surprise that the Constitution’s cover letter was cited at length by Senator George Bibb on January 30, 1833. In particular, Bibb suggested that the South Carolina dispute afforded an “ample field for exerise of intellect with intellect; sufficient room for the exercise of a mutual spirit of amity, concession and conciliation, without resorting to the sword and bayonet, to put up or to put down the political creed of the one or the other party.”

While Calhoun was a strong proponent of minority rights, it is unfortunate that he was focused on protecting the rights of slaveholders. It is clear that Calhoun had a differing interpretation of the Constitution, states rights, and the cover letter. Published posthumously in 1851, Calhoun’s Disquisition on Government and Discourse on the Constitution made arguments that are roundly rejected today. Nevertheless, Calhoun’s treatise likely contributed to sectionalism, succession, and the Civil War.

For example, Daniel Farber in the book Lincoln’s Constitution observes that the cover letter had a “strongly nationalistic bent” since it emphasized the imperative of “consolidation of our Union.” The cover letter describes the framers’ goal of “fully and effectually vesting” required powers in the national government while simultaneously checking and balancing those new powers.

By contrast, for Calhoun consolidation of federal power was absolutely anathema. Calhoun’s solution was to redine the word “federal” to mean “not national.” Harry Jaffa writes in the book A New Birth of Freedom: Abraham Lincoln and the Coming of the Civil War that for Calhoun, Madison’s version of a “party federal, partly national” government was an impossibility. In other words, Jaffa observes that Calhoun’s interpretation of the cover letter was “the exact opposite of what Calhoun imputes to it.”

Beginning in the 1850’s, Abraham Lincoln also quoted the cover letter. Although Lincoln and Calhoun carefully studied the cover letter, they drew very different conclusions. According to Joseph Ellis, “Lincoln maintained he was acting as the agent of the founding generation, so that the Union cause spoke for the true meaning of the American Revolution.” Due to the breath and depth of Lincoln’s speeches, they will be separtely discussed below in Section 5.

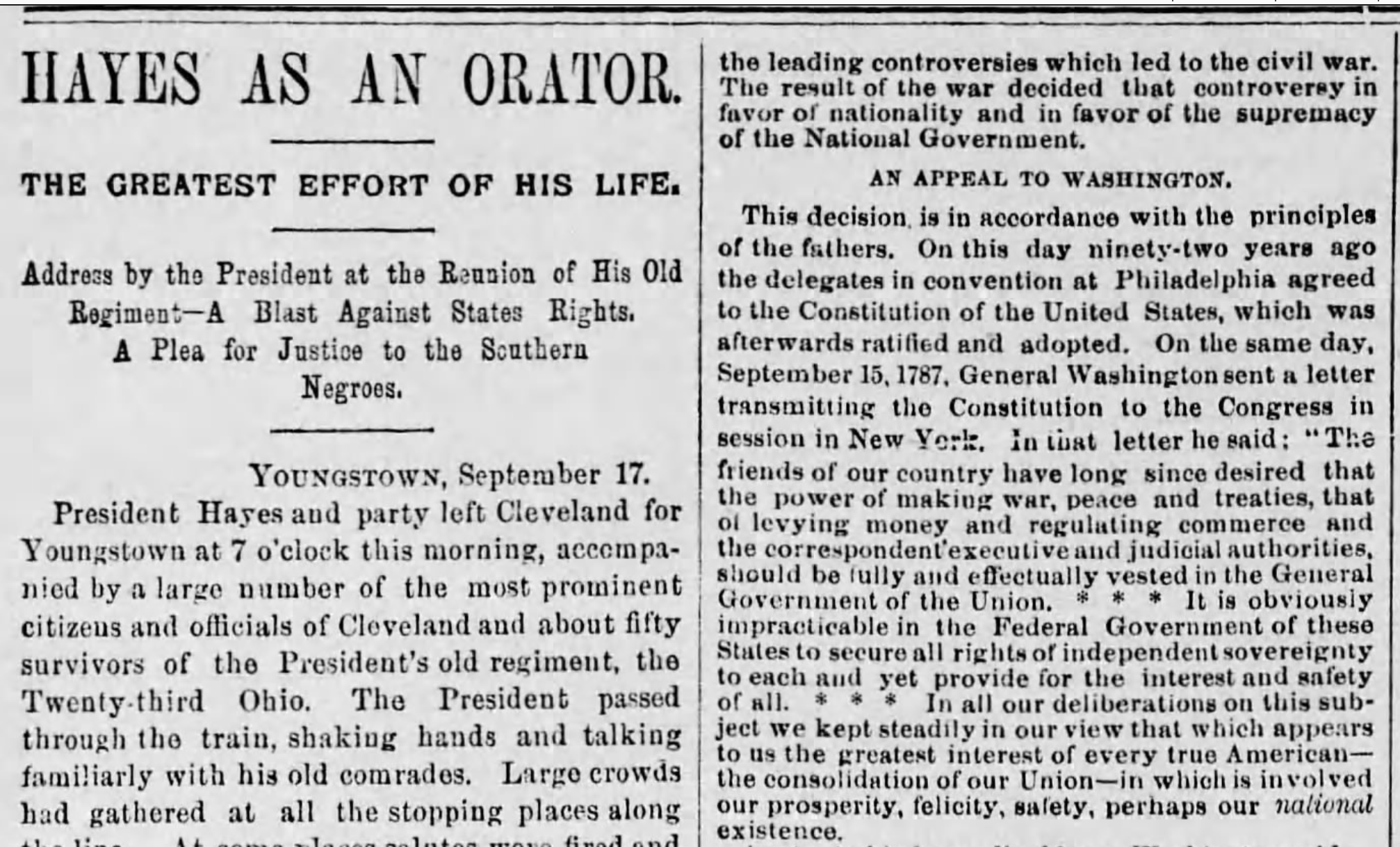

Reconstruction ended with the contested election of 1876. Republican President Rutherford B. Hayes was declared the winner in exchange for the removal of federal troops from the South. While a member of Congress, Hayes helped pass the Civil Rights Act of 1866. As President Hayes publically spoke in favor of civil rights for former slaves and against unrestrained states rights.

Copied below is an excerpt from Hayes’ speech in Youngstown, Ohio to his former military regiment on September 17, 1879. On the 92nd anniversary of the cover letter, Hayes quotes at length from Washington’s “letter transmitting the Constitution to Congress in session in New York.” Hayes asserts that the letter supports the outcome of the Civil War. According to Hayes, “[t]he result of the war decided that controversy in favor of nationality and in favor of the supremacy of the National Government.”

The only president to serve two non-consecutive terms, Grover Cleveland, also quoted the cover letter. Cleveland was also the first Demcrat elected after the Civil War. As the centenial of the Constitution approached, on March 4, 1885, Cleveland’s First Inaugural Address praised the cover letter’s spirit of amity and mutual concession in the context of the “large variety of diverse and competing interests subject to Federal control.” In the speech Cleveland set the goal of administering the country “in the same spirit” that prevailed “when the Constitution had its birth.”

On this auspicious occasion we may well renew the pledge of our devotion to the Constitution, which, launched by the founders of the Republic and consecrated by their prayers and patriotic devotion, has for almost a century borne the hopes and the aspirations of a great people through prosperity and peace and through the shock of foreign conflicts and the perils of domestic strife and vicissitudes.

By the Father of his Country our Constitution was commended for adoption as “the result of a spirit of amity and mutual concession.” In that same spirit it should be administered, in order to promote the lasting welfare of the country and to secure the full measure of its priceless benefits to us and to those who will succeed to the blessings of our national life. The large variety of diverse and competing interests subject to Federal control, persistently seeking the recognition of their claims, need give us no fear that “the greatest good to the greatest number” will fail to be accomplished if in the halls of national legislation that spirit of amity and mutual concession shall prevail in which the Constitution had its birth.

In 1950 Harry Truman impliedly recognized another dimension of diversity in the context of the admission of Alaska and Hawaii into the Union. Truman also addressed the concern that these new states would be afforded representation in the Senate disproportionate to their population. Click here for a link to Truman’s May 5, 1959 letter to Senator O’Mahoney:

This argument is not only entirely without merit, but also directly attacks a basic tenet of the constitutional system under which this nation has grown and prospered. Without the provision for equal representation in the Senate of all states, both great and small, regardless of population, there probably would have been no United States. This was one of the great compromises which the Federalist says was a result “not of theory, but of a spirit of amity, and that mutual deference and concession which the peculiarity of our political situation rendered indispensable.” There is no justification for denying statehood to Alaska and Hawaii on the basis of an issue which was resolved by the Constitutional Convention in 1787.

In embracing statehood for Alaska and Hawaii, Truman was honoring a long tradition which is illustrated by the Address to the People of California in 1859. The following Address was prepared by the delegates who wrote the California Constitution, 100 years before Truman’s letter. In the Address, the framers of the California Constitution recognized with pride their diversity despite the fact that they were “coming from every part of the world, speaking various languages, and imbued with different feelings and prejudices”:

Although born in different climes, coming from different States, imbued with local felings, and educated perhaps with predilections for peculiar institutions, laws, and customs, the delegates assembled in Convention as Californias, and carried on their deliberations in a spirit of amity, compromise and mutual concession for the public weal.

It is not surprising that several U.S. Senators, serving in the world’s greatest deliberative body, have occassionally invoked the cover letter. Senator Robert Byrd, the longest serving Senator with a deep respect for the Senate’s rules and history, cited the cover letter in a 1995 speech about civility. Senator Edward Kennedy cited the spirit of the cover letter and Federalist 62 (which quotes it) in a 2010 speech assailing the “nuclear option” for judicial confirmations. More recently, Senator Mike Crapo cited the cover letter in a 2012 column commemorating the cover letter’s 225th anniversary.

5. Abraham Lincoln and the Constitution’s Cover Letter

Abraham Lincoln was a student of history who was very familiar with the founding generation. He would need all of his knowledge and skills upon taking office on March 4, 1861. Upon his inauguration, seven confederate states had already seceded from the Union.

On February 11 Lincoln left Springfield, Illinois to begin his trip to Washington. He was arguably confronted with challenges that exceeded the task George Washington faced when he first assumed the Presidency in 1789. Fortunatlely Lincoln took his oath to defend the Constitution seriously. Thankfully, he was armed with a strength of charater and the clarity of a deep understanding of the Constitution.

In the four months between his election and his inauguration, Lincoln quietly assured his allies to take a united stand against secession. “Stand firm,” Lincoln urged. Given his oath to protect the Constitution, Lincoln advised fellow Republicans to reject “compromise of any sort,” but rather “hold firm, as with a chain of steel.”

As described by Professor William Woodward, “Lincoln carefully crafted an inaugural address that began in conciliation, switched subtly to firm warning, and ended in a heartfelt overture of peace.”

Lincoln famously concluded his First Inaugural with an appeal to “the better angels of our nature”:

We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained, it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battle-field and patriot grave to every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.

Over the past decade Lincoln had recognized the value of the cover letter.

In his three-hour long Peoria Speech of October 16, 1854, Lincoln assailed the Kansas Nebraska Act. Lincoln marshalled together the moral, legal, and economic case against slavery. He also cited the founders to make historic arguments against slavery.

The Missouri Compromise ought to be restored. For the sake of the Union, it ought to be restored. We ought to elect a House of Representatives which will vote its restoration. If by any means, we omit to do this, what follows? Slavery may or may not be established in Nebraska. But whether it be or not, we shall have repudiated—discarded from the councils of the Nation—the SPIRIT of COMPROMISE; for who after this will ever trust in a national compromise? The spirit of mutual concession—that spirit which first gave us the constitution, and which has thrice saved the Union—we shall have strangled and cast from us forever. And what shall we have in lieu of it? The South flushed with triumph and tempted to excesses; the North, betrayed, as they believe, brooding on wrong and burning for revenge. One side will provoke; the other resent. The one will taunt, the other defy; one agrees [aggresses?], the other retaliates. Already a few in the North, defy all constitutional restraints, resist the execution of the fugitive slave law, and even menace the institution of slavery in the states where it exists…We thereby restore the national faith, the national confidence, the national feeling of brotherhood. We thereby reinstate the spirit of concession and compromise—that spirit which has never failed us in past perils, and which may be safely trusted for all the future.

In his House Divided speech in 1858, Lincoln explained that:

A house divided against itself cannot stand. I believe this government cannot endure permanently half-slave and half-free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved – I do not expect the house to fall – but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing or all the other.

During the war, in his Second Annual Message of December 1, 1862, Lincoln quoted the cover letter as follows:

Among the friends of the Union there is great diversity of sentiment and of policy in regard to slavery and the African race amongst us. Some would perpetuate slavery; some would abolish it suddenly and without compensation; some would abolish it gradually and with compensation: some would remove the freed people from us, and some would retain them with us; and there are yet other minor diversities. Because of these diversities we waste much strength in struggles among ourselves. By mutual concession we should harmonize and act together. This would be compromise, but it would be compromise among the friends and not with the enemies of the Union. These articles are intended to embody a plan of such mutual concessions. if the plan shall be adopted, it is assumed that emancipation will follow, at least in several of the States.

6. Publications containing the Cover Letter

The cover letter was widely printed in the papers during the ratification debates. For many years it was also widely published in legal texts, statutory compilations, and even procedural manuals for Congress and state legislatures. The following non-exhaustive examples serve to illustrate the wide range of publications that printed the cover letter, particularly during the formative years of the Federal government:

- Perpetual Laws of Massachusetts (1801): Published by patriot publisher, Isaiah Thomas, the Perpetual Laws of Massachusetts was the first collection of Massachusetts statutes in 1788, the year of ratification of the Constitution. Click here for a discussion of Isaiah Thomaswho became the Bill Gates/Jeff Bezos of his day.

- Hening’s Laws of Virginia: Published by William Waller Hening, this first codification of the laws of Virgina was an influential work for many years. Click here for a discussion of Hening’s 13 volume work, which was compiled in part from books in Thomas Jefferson’s personal library.

- The American Citizen’s Sure Guide: Being a Collection of Most Important State Papers: Published in 1804, the guide illustrates that the cover letter was deemed an important early record, which was printed behind the Constitution.

In the weeks to come, this section will be populated with a discussion of these and additional sources that published the cover letter in early American history.