President Andrew Jackson’s Force Act of 1833:

[4 Stat. 632, Acts of 22nd Congress]

During the Nullification Crisis of 1832-1833, South Carolina and Vice President John Calhoun declared that federal tariffs, including the Tariff of 1828 (the “Tariff of Abominations”), were unconstitutional. According to Vice President Calhoun’s theory of nullification and states’ rights, South Carolina could declare federal law null and void within state boundaries.

The Tariff was 1828 was adopted during the Presidency of John Quincy Adams (click here for a link to a discussion of the Tariff of Abominations) and the resulting controversy ultimately led to Jackson’s election in 1832. The compromise Tariff of 1832 was an effort by President Jackson to defuse the confrontation, but did not satisfy Calhoun.

On November 24, 1832, a specially called convention in South Carolina adopted the “Ordinance of Nullification,” declaring the Tariffs of 1828 and 1832 unconstitutional. In addition to asserting that federal tariffs were void and unenforceable in South Carolina, South Carolina also began to take military preparations to resist federal intervention as the legislature voted to forbid the collection of duties within the state.

Click here for a copy of South Carolina’s Nullification Ordinance

President Jackson was outraged and privately threatened to hang Calhoun. Publicly Jackson declared that nullification was treason and the nullifiers were traitors. Jackson began strengthening federal forts in South Carolina and ordered General Winfield Scott to Charleston with several revenue cutters and a warship.

In the Senate, Daniel Webster argued that the Constitution was not a mere compact between the states. To Webster the Constitution was a “executed contract”, an agreement to set up a permanent government, supreme within its sphere of lawful power. The “Great Pacificator,”Henry Clay intervened with a solution. Pursuant to Clay’s compromise, tariff rates would be lowered annually until 1842 when rates would reach the same levels as in 1816.

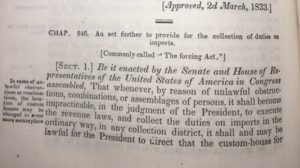

The crisis was resolved with the simultaneous adoption of the Compromise Tariff of 1833 and President Jackson’s “Force Act.” The Force Act expanded Presidential powers and explicitly authorized the President to use the U.S. military to enforce federal law. South Carolina was pacified with lower tariff rates. Both sides could claim a political victory. South Carolina reconvened its convention and repealed its Nullification Ordinance. Nevertheless, the seeds of controversy over states’ rights and nullification had been planted since South Carolina refused to repudiate the doctrine of nullification.

Section 5 of the Force Act provided:

“That whenever the President of the United States shall be officially informed, by the authorities of any state, or by a judge of any circuit or district court of the United States, in the state, that, within the limits of such state, any law or laws of the United States, or the execution thereof, or of any process from the courts of the United States, is obstructed by the employment of military force, or by any other unlawful means, too great to be overcome by the ordinary course of judicial proceeding, or by the powers vested in the marshal by existing laws, it shall be lawful for him, the President of the United States, forthwith to issue his proclamation, declaring such fact or information, and requiring all such military and other force forthwith to disperse; and if at any time after issuing such proclamation, any such opposition or obstruction shall be made, in the manner or by the means aforesaid, the President shall be, and hereby is, authorized, promptly to employ such means to suppress the same, and to cause the said laws or process to be duly executed . . .”

Click here for a copy of the Act

Interestingly, the Force Act contained a trigger to prevent President Jackson from using force unilaterally. According to Section 5 of the Act, as a precondition to the use of force, the “authorities of any state” or a federal judge needed to inform the President that federal law or the execution thereof, or any process of the federal courts was “obstructed” by military force or any other unlawful means “too great to be overcome by the ordinary course of judicial proceedings.” In other words, the Force Acts attempted to default to the judicial system for enforcement. The second trigger in the Act was the requirement of a Presidential proclamation ordering the South Carolinian “military and other force” forthwith to disperse. Only thereafter, if the “opposition or obstruction” continued would the President be empowered to employ “such means to suppress” as would be necessary.

By way of background, the South was suffering through a severe economic downturn in the 1820s. Following the War of 1812, America initiated a protectionist/merchantilist policy to develop industry in the North. Yet, beginning in 1819 (with the Panic of 1819), the country experience its first major financial crisis which lasted during the early 1820s. Many Southerners blamed national tariff policy, which worsened political rifts with the north. The gradual exhaustion of the soil in South Carolina, which was now in competition from newly opened – and more fertile – western lands, did help as the South Carolina economy stagnated in the 1820s.

Calhoun had proposed his theory of nullification in an anonymously published pamphlet entitled “The South Carolina Exposition and Protest.” According to the theory, a state could hold a nullifying convention to declare a federal law unconstitutional. Unless and until 3/4 of the states amended the U.S. Constitution to explicitly granted Congress the questioned authority, the law would remain null and void. If 3/4 of the states ratified the amendment, the nullifying state would need to abide by the law or succeed.

Primary sources (Library of Congress)