Lincoln’s Militia Act of 1862

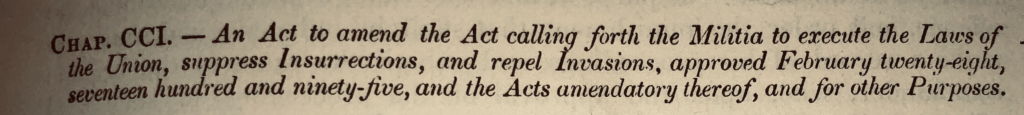

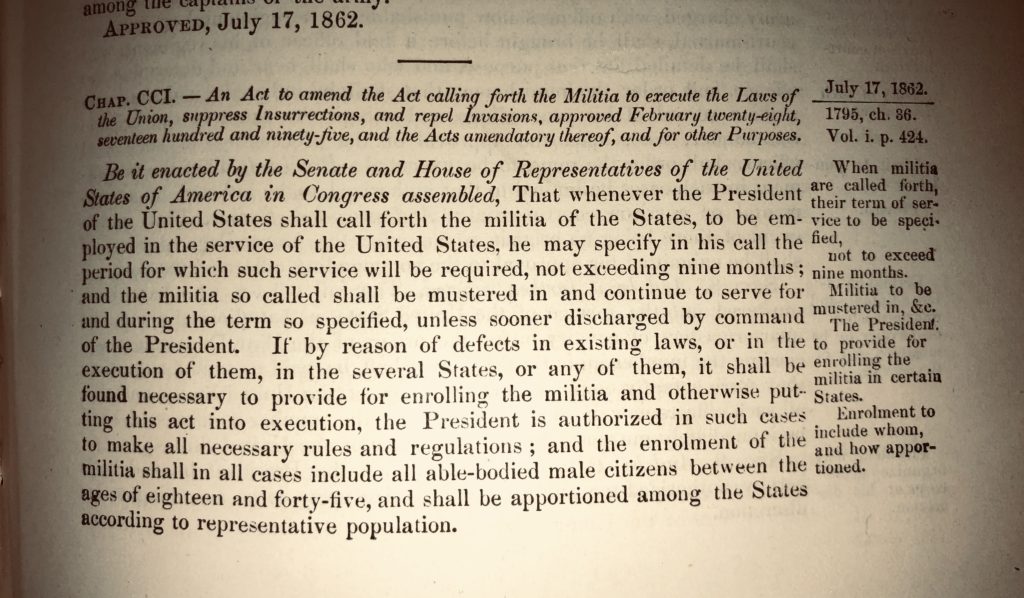

Chapter CCI, Second Session, 37th Congress (12 Stat. 597)

The Militia Act of 1862 was enacted early in the Civil War to enable President Lincoln to enlist African-American soldiers. The Act amended the Milita Act of 1792 which had previously limited recruitment to “free able-bodied white males.” By the end of the Civil War, approximately 200,000 African American troops would serve in the Union Army and Navy.

The primary purpose of the Militia Act of 1862 was to enable African Americans to join the Union Army in non-combat roles behind the front lines. The Act was controversial for several reasons. While the Act was a necessary first step, abolistionists criticized the Act as not going far enough, since it largely relegated African American troops to manual labor and non-combat roles. Moreover, newly recruited African American soldiers were paid less than their white counterparts.

President Lincoln was not satisfied with the 1862 Act, which was a compromise that avoided provoking the border states of Missouri, Kentucky, Maryland and Delaware (which had remained loyal to the Union). In issuing the Emancipation Proclamation, to be effective January 1, 1863, Lincoln made clear that African American troops would be permitted in combat units:

And I further declare and make known, that such persons of suitable condition, will be received into the armed service of the United States to garrison forts, positions, stations, and other places, and to man vessels of all sorts in said service.

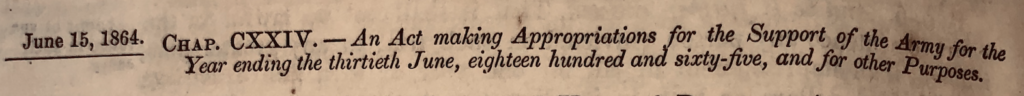

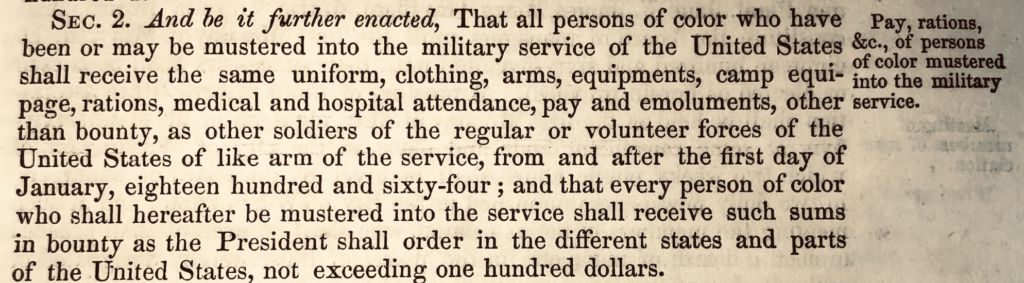

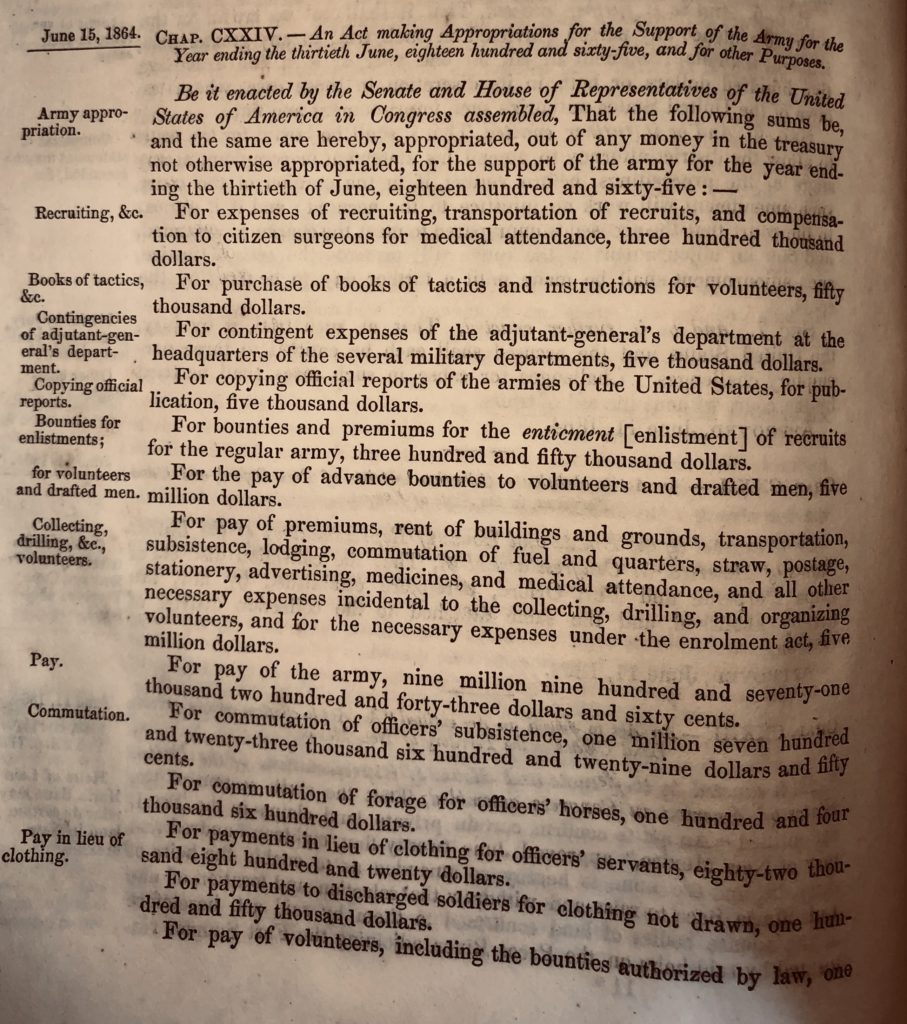

As initially adopted in 1862, soldiers “of African descent” were only paid $10 a month, minus a clothing allowance, while white combat troops were paid $12 per month plus a clothing allowance. Many African American regiments refused their unequal pay until June 15, 1864, when Congress amended the law to grant equal pay for all soldiers.

Sections 12 and 13 of the 1862 Act are copied below:

SEC. 12. And be it further enacted, That the President be, and he is hereby, authorized to receive into the service of the United States, for the purpose of constructing entrenchments, or performing camp service, or any other labor, or any military or naval service for which they may be found competent, persons of African descent, and such persons shall be enrolled and organized under such regulations, not inconsistent with the Constitution and laws, as the President may prescribe.

SEC. 13. And be it further enacted, That when any man or boy of African descent, who by the laws of any State shall owe service or labor to any person who, during the present rebellion, has levied war or has borne arms against the United States, or adhered to their enemies by giving them aid and comfort, shall render any such service as is provided for in this act, he, his mother and his wife and children, shall forever thereafter be free, any law, usage, or custom whatsoever to the contrary notwithstanding: Provided, That the mother, wife and children of such man or boy of African descent shall not be made free by the operation of this act except where such mother, wife or children owe service or labor to some person who, during the present rebellion, has borne arms against the United States or adhered to their enemies by giving them aid and comfort.

Discriminatary pay rates were rectified by Lincoln two years later. The 1864 Amendments (Chapter CXXIV) provided that “all persons of color” shall receive the same “uniform, clothing, arms, equipments, camp equipments, rations, medical an hospital attendance, pay and emoluments, other than bounty, as other soliders…”

Results of the Act

In the South the Union’s use of African American troops was considered inflammatory. Confederate generals declared that captured black soldiers would be summarily executed and that white officers of black units would be put on trial for promoting insurrection. Given the opportunity, Confederate General Bedford Nathan Forrest’s soliders massacred hundreds of surrendering black soldiers at Fort Pillow in Tennessee in April of 1864.

Abolitionist Frederick Douglass argued that, “[o]nce let the black man get upon his person the brass letters, U.S.; let him get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder and bullets in his pocket, and there is no power on earth which can deny that he has earned the right to citizenship.”

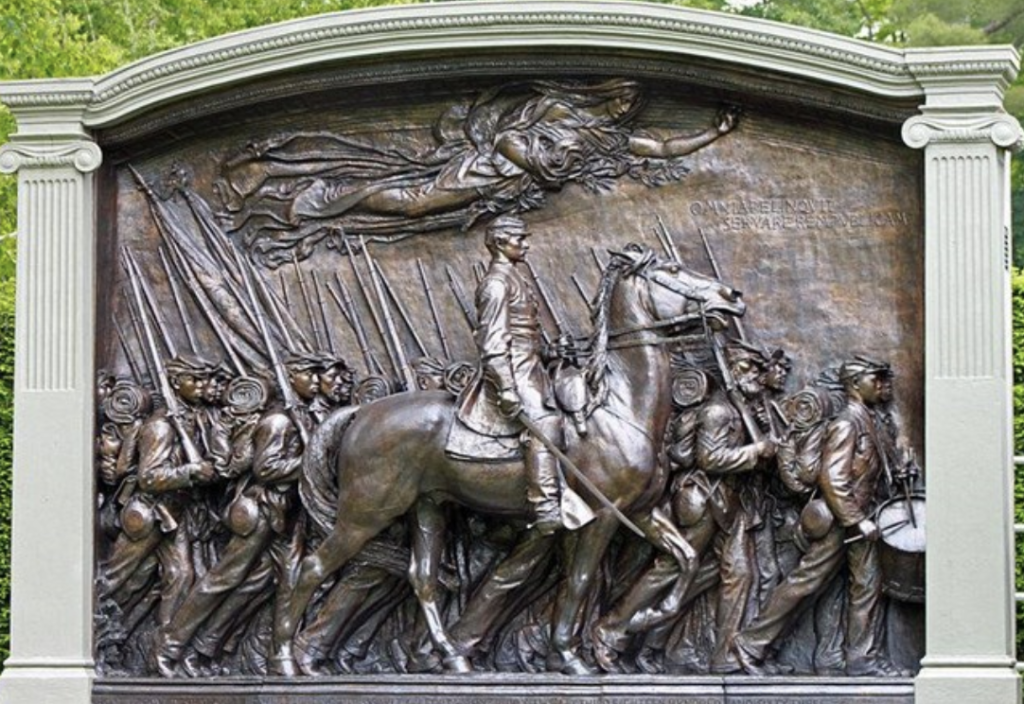

On July 18, 1863, one of the first all African American units, the 54th Massachusetts Regiment, lost almost 50% of its troops in an assault on the heavily fortified earthworks at Fort Wagner, which protected the port of Charleston, South Carolina. The widely disseminated story of the 54th’s heroism helped combat stereotypes and reverse public opinion.

54th Massachusetts Regiment

The Emancipation Proclamation opened the door to African Americans in the infantry. At the time, state governors were responsible for the raising of miltary regiments. Massachusetts and Kentucky became the first states to respond by forming the famous Massachusetts Fifty-fourth Regiment and the 1st Kansas Colored Volunteer Infantry Regiment.

Prominent abolitionists actively recruited for the 54th. Frederick Douglass’ two sons were among the first volunteers. While the unit was formed in Massachusetts, members volunteered from several states. The unit was placed under the command of Harvard educated Robert Gould Shaw, himself the son of abolitionists.

Known as the “Swamp Angels,” the Massachusetts 54th saw more than its share of combat. The 54th’s bloody assault at Fort Wagner was the first time that an African American unit led an attack during the war. The battle also produced the first African American Medal of Honor recipient. Yelling, “Boys, the Old Flag never touched the ground!,” Sergeant William Harvey rallied the troops by grabbing the flag after the initial flag bearer was injured during the battle. The unit’s commander, Robert Shaw, was one of the first to die in the battle, leading the charge.

The story of the 54th was dramatized in the movie Glory staring Denzel Washington as Private Tripp, Morgan Freeman, Cary Elwes, and Matthew Broderick as Shaw.

Portions of the 1862 and 1864 Acts are pictured below:

Additional reading:

Black Union soldiers fought a costly battle for equal pay (Military Times)

How the Men of Glory Stood Up to the U.S. Government (The Atlantic)