The 12th Amendment and the Election of 1800

The election of 1800 was transformative. Vice President Thomas Jefferson defeated incumbent President and Revolutionary era senior statesman, John Adams. Following the election, Jefferson’s Democratic-Republican party would become ascendant. Jefferson’s victory would also mark the permanent demise of the Federalist party. The bitter election exposed defects with the Electoral College, which would be corrected by the 12th Amendment. Perhaps most importantly, the election represented a successful, peaceful transfer of power between rival parties.

Election of 1800 – background

Referred to by Jefferson as the “Revolution of 1800”, the election of 1800 was the 4th presidential election in American history. Jefferson’s narrow victory would usher in the gradual demise of the Federalist party and cement regional differences between the Federalist stronghold in New England and Democratic-Republican control of the South and West.

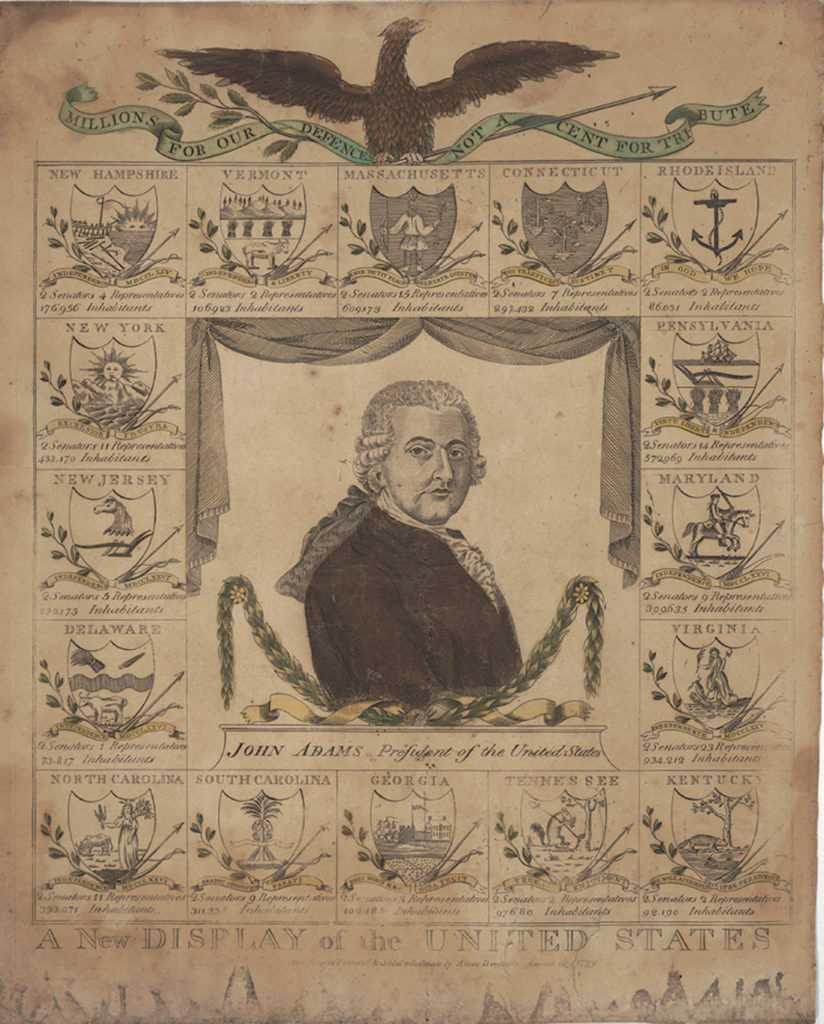

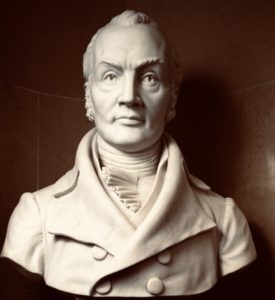

The election of 1800 was a rematch of the election of 1796, between President Adams and his Vice President, Thomas Jefferson. While Adams and Jefferson would become close friends later in life, they represented different visions for America. Although Adams and Jefferson did not directly campaign or criticize each other, their surrogates waged a divisive and dirty newspaper campaign.

The emergence of political parties was not contemplated by the Constitution’s framers. As a result of oversights in the design of Article II of the Constitution, in 1796 Adams replaced Washington as President, but Adams’ rival, Thomas Jefferson, was elected Adams’ Vice President. The flaws with the Electoral College would be further exposed in the election of 1800.

Leading into the 1800 election, the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans sought to avoid the dilemma presented in 1796 when two rivals were elected president and vice president. For the first time in American history, the two national parties selected a combined party ticket with nominees for president and vice president.

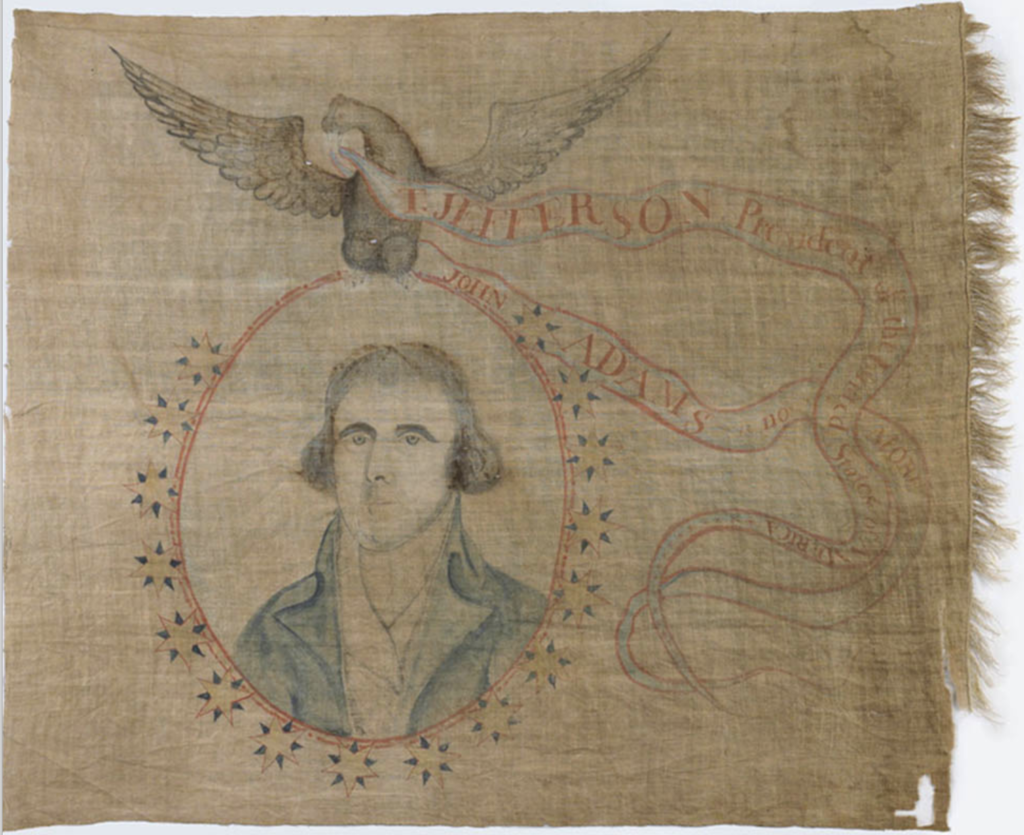

In an effort to generate regional balance, Jefferson from Virginia aligned with Aaron Burr from New York. Burr had been successful in early 1800 when he played a leading role in securing Republican victories in New York legislative races.

In addition to Democratic-Republican gains in New York, Jefferson would also benefit from pre-election developments in Virginia. Rather than splitting its vote among Congressional districts, Virginia converted into a winner take all state going into the 1800 election. This strategic move orchestrated by James Monroe guaranteed that Jefferson would garner all of Virginia’s delegates.

Recognizing the emerging Democratic-Republic strength in New York, Adams selected Charles Cotesworth Pinckney from South Carolina as his running mate. While Adams could depend on support in New England, the only way to be re-elected in the face of New York’s support for Jefferson, was to win in Pennsylvania and South Carolina.

In 1800, the original 13 colonies had grown to 16 states. In 11 states, delegates would be selected by state Legislatures, leaving only 5 states where delegates were selected by popular election. While the Democratic-Republicans were largely united behind Jefferson, the Federalists were divided between “High Federalists” led by Alexander Hamilton and the more moderate Federalists who supported Adams.

Due to the active campaigning by surrogates and the understanding that 1800 would be a hard fought election, voter turnout increased from 15% to 40%. In the battleground state of Pennsylvania, voter turnout increased by more than 50%. While Adams did well in Pennsylvania and North Carolina (along with the Northeast), he could not overcome Jefferson’s gains in New York and the new states of Tennessee and Kentucky.

Election of 1800 – outcome

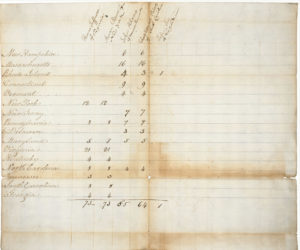

When the Electoral College voted, the results were 73 votes each for Jefferson and Burr, easily defeating Adams and Pinckney with 65 and 64 votes. To avoid a tie between Adams and Pinckney, the Federalists wisely cast one electoral vote for John Jay.

Unlike the Federalists who purposely avoided a tie between their two candidates, the Democratic-Republicans cast all electoral votes for Jefferson and Burr, who each won 73 electoral college votes.

As originally provided by Article II, Section 1 of the Constitution, a tie in electoral college votes triggers a “contingent” runoff election in the House of Representatives. “But in chusing the President, the Votes shall be taken by States, the Representation from each State having one Vote…”

Although Aaron Burr had agreed to run as Jefferson’s vice president, he did not concede the presidency when the electoral vote resulted in a 73 – 73 tie. The election was thrown into the House, where ironically the “lame duck” Federalists were required to decide who would be the next president in the runoff between Jefferson and Burr.

The 16 House ballots were unsealed in the House on February 11. The majority of Federalists voted for Burr, awarding him 6 of the 8 states controlled by the Federalists. All seven Democratic-Republican states voted for Jefferson, along with Georgia’s sole Federalist representative. Maryland was forced to cast a blank ballot when a 4 – 4 split emerged within the delegation.

Over the course of the next week, from February 11 to February 17, the House cast a total of 35 indecisive ballots. Each time, Jefferson received the votes of eight state delegations, but fell one vote short of the nine state threshold. The minority Democratic-Republican states in the House were faced with the daunting prospect of Burr’s election engineered by the Federalists, or a continuing deadlock, which would leave the Federalist Secretary of State, John Marshall as acting President. Alexander Hamilton, the leader of the High Federalists, ultimately threw his support for Jefferson. In Hamilton’s mind, Jefferson was “by far not so dangerous a man” as Burr. This would contribute to their duel in 1804.

Finally, on the 36th ballot on February 17, the single Delaware Federalist representative switched to cast a blank ballot (along with other Federalists from Maryland and Vermont). As a consequence, Jefferson won 10 states, Burr won 4 states, and states two states abstained.

1800 Presidential Campaign

The 1800 campaign was a low point in civility for presidential elections. Although Jefferson and Adams were publicly cordial, their surrogates were ruthless. Jefferson’s critics labeled him “a mean spirited, son of a half-breed Indian squaw, sired by a Virginia mulatto father.” Federalists feared that Jefferson was too pro-French. He was also attacked as an atheist.

Adams was referred to as “lord rotundity” and criticized as a pompous aristocrat. Rumors circulated that during Adams’ time in London as the American ambassador, he tried to arrange for his son to marry a daughter of King George III. Among the more colorful insults was that Adams was a “hideous hermaphroditical character, which has neither the force and firmness of a man nor the gentleness and sensibility of a woman.”

During this “genteel” period of American politics, the candidates tried to minimize their ambition for political office. Nevertheless, Jefferson began advertising the fact that he had drafted the Declaration of Independence. Adams’ supporters exposed the allegation of Jefferson’s relationship with Sally Hemings.

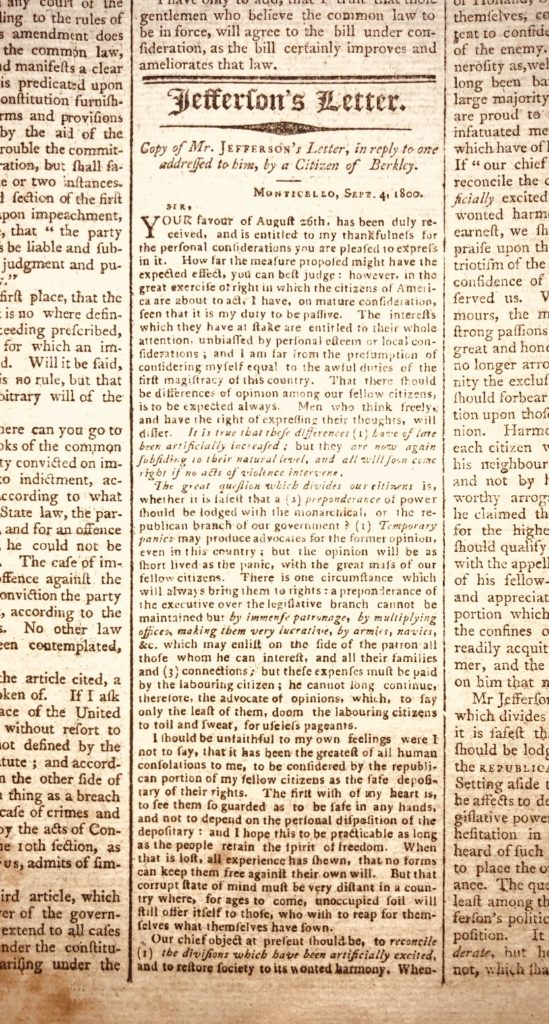

During this period, letters from Jefferson would be released for publication in friendly newspapers. A pre-election letter to a fellow Virginian dated September 4, 1800 illustrates Jefferson’s thinking and priorities:

[T]he great question which divides our citizens is whether it is safest that a preponderance of power should be lodged with the monarchical or the republican branch of our government? temporary panics may produce advocates for the former opinion even in this country; but the opinion will be as shortlived as the panic with the great mass of our fellow citizens. there is one circumstance which will always bring them to right: a preponderance of the executive over the legislative branch cannot be maintained but by immense patronage, by multiplying offices, making them very lucrative, by armies, navies, &c which may enlist on the side of the patron all those whom he can interest, & all their families & connections. but these expences must be paid by the labouring citizen. he cannot long continue therefore the advocate of opinions, which, to say only the least of them, doom the labouring citizen to toil & sweat for useless pageants. . . . our chief object at present should be to reconcile the divisions which have been artificially excited and to restore society to it’s wonted harmony. whenever this shall be done it will be found that there are very few real opponents to a government elective at short intervals.

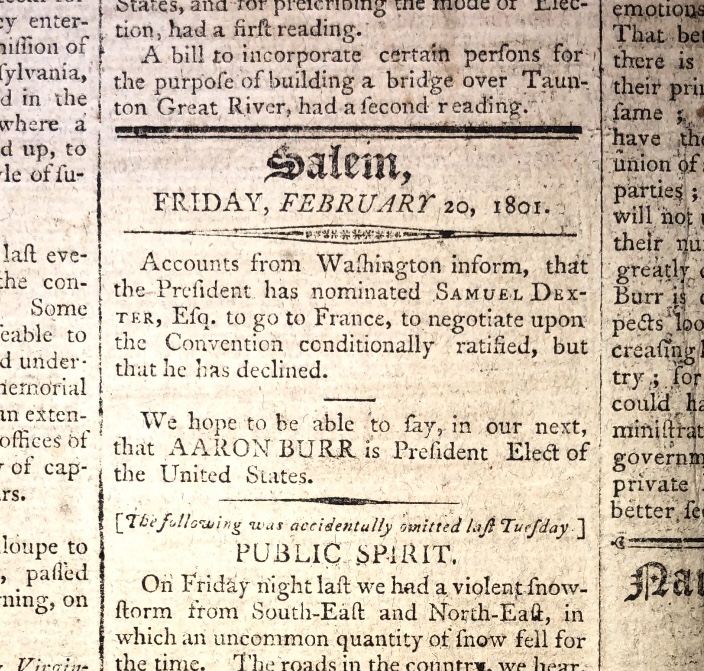

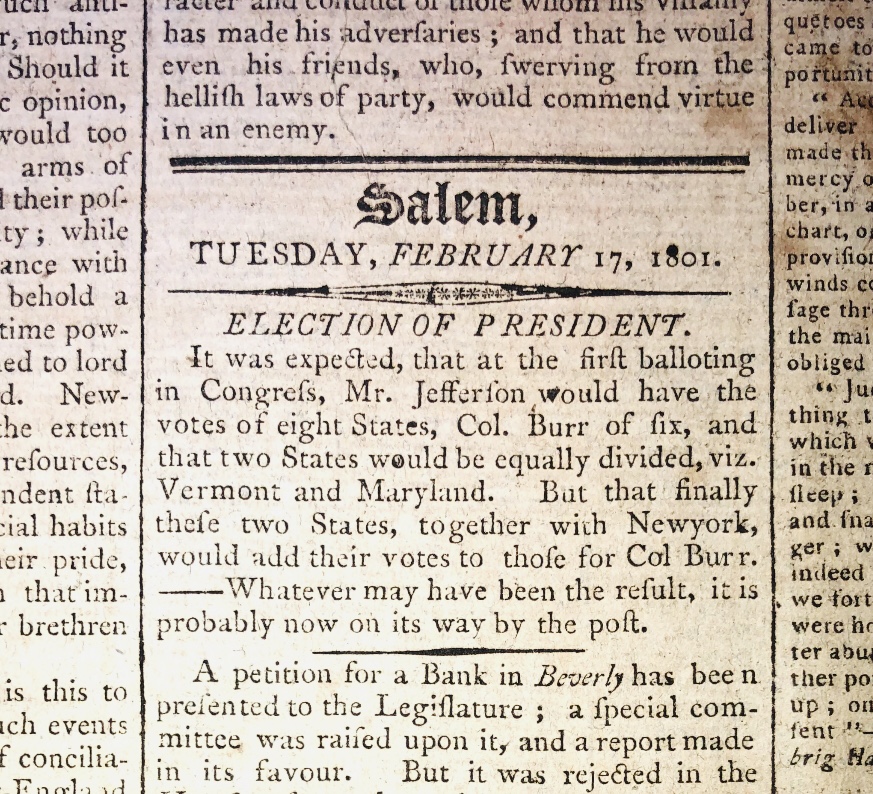

Copied below are images from a sample newspaper, which also includes speculation about the outcome of the election and a possible Burr victory.

Two Votes Per Delegate

As originally designed, Article II of the Constitution required each electoral delegate to vote for two presidential candidates. To minimize large state support for “favorite sons,” electoral delegates were precluded for voting for two candidates from the same state. This procedure was intended to increase the chances of smaller states winning the presidency, but had unintended consequences. The problem with this 2 vote procedure was exposed by the 1800 election.

The solution, to avoid an electoral college tie between president and vice president, was for parties to identify one elector to throw away a vote for the party’s vice president. Due to difficulties with communication and travel delays, the Democratic-Republicans bungled this task. The unyielding Burr, for his part, refused to concede to Jefferson when they tied 73 to 73.

12th Amendment fixes some Electoral College defects

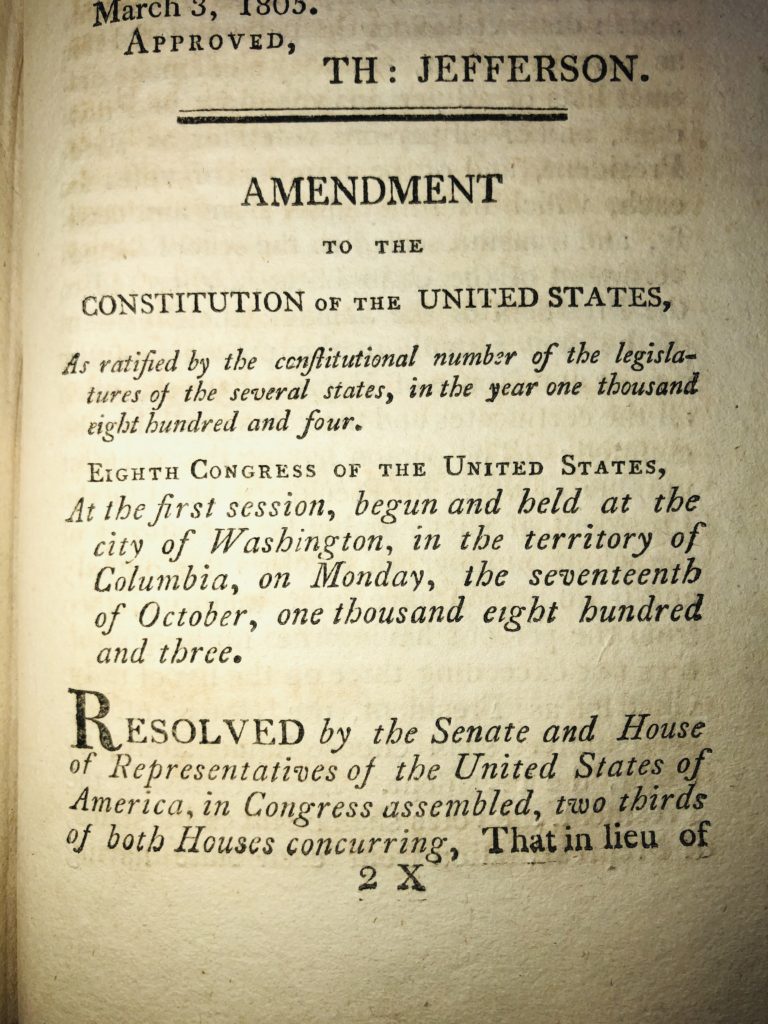

The 12th Amendment was proposed by Congress in December of 1803 to correct the flaws that became evident in the 1796 and 1800 elections. The Amendment was ratified in June of 1804, in advance of the presidential election of 1804.

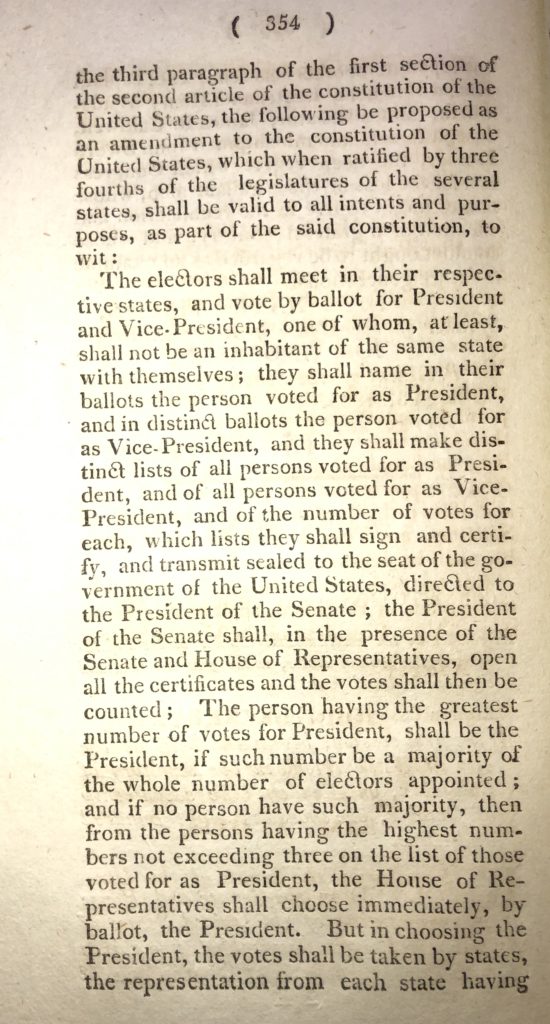

Among other things, the 12th Amendment revised the two vote per delegate procedure for the original Electoral College. After the 12th Amendment, each elector casts separate votes for president and vice president. If no presidential candidate receives a majority, the House selects from the top three candidates (instead of the top 5 as originally provided in 1787).

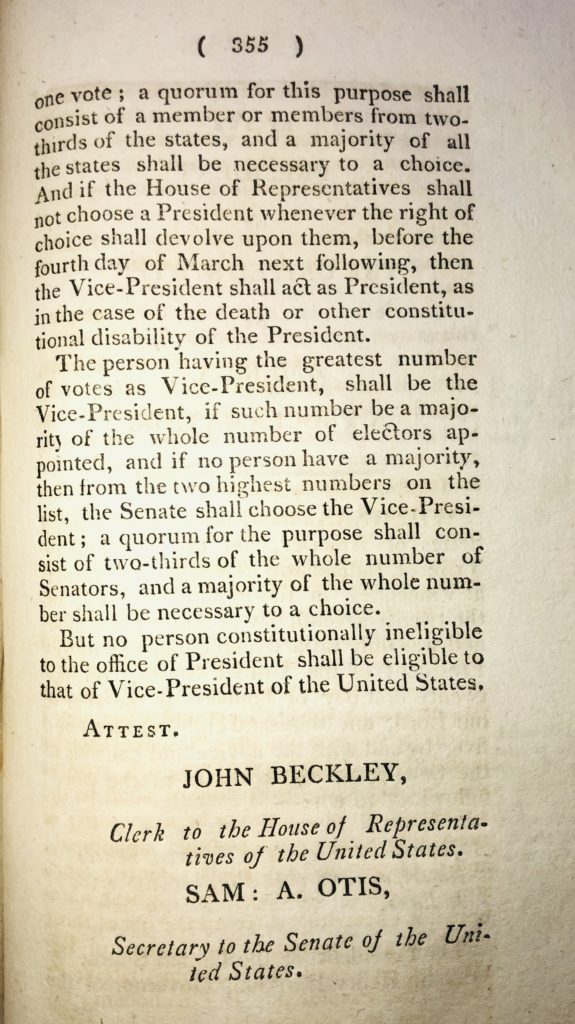

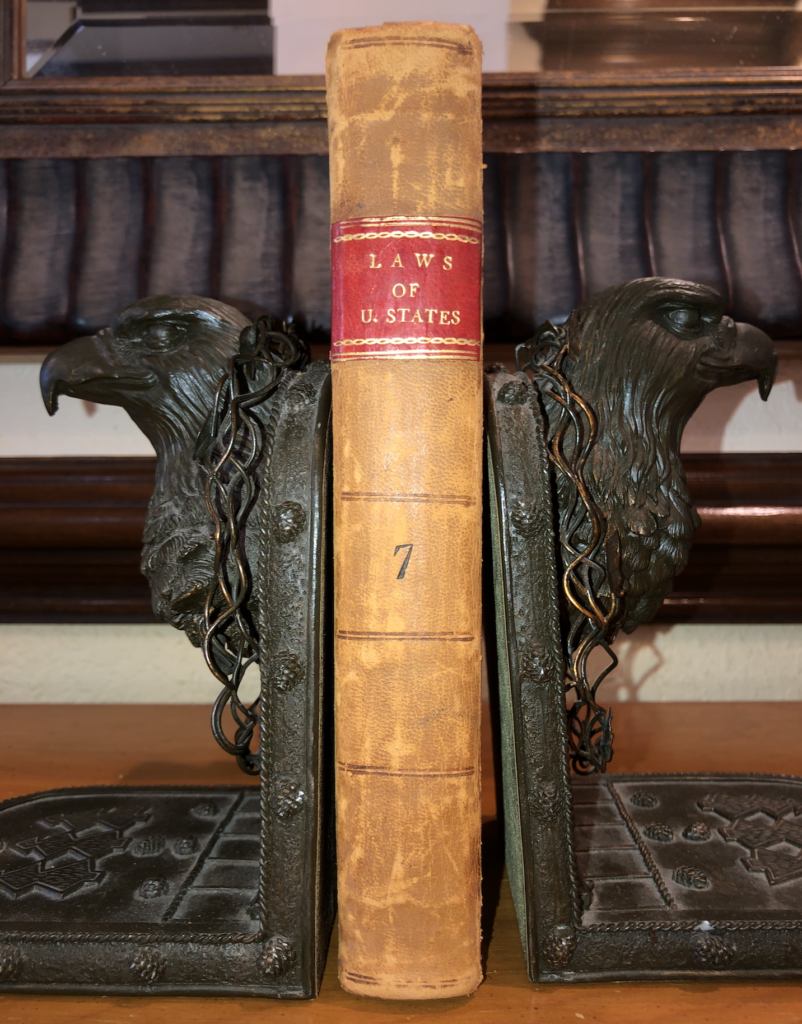

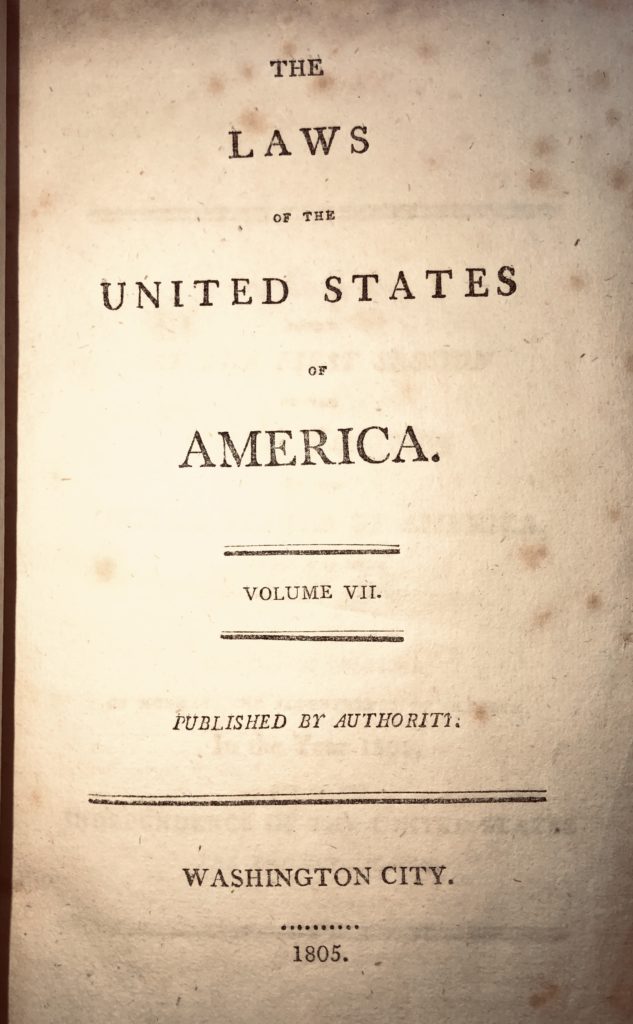

Copied below are images of the 12th Amendment contained in the Laws of the Eighth Congress.