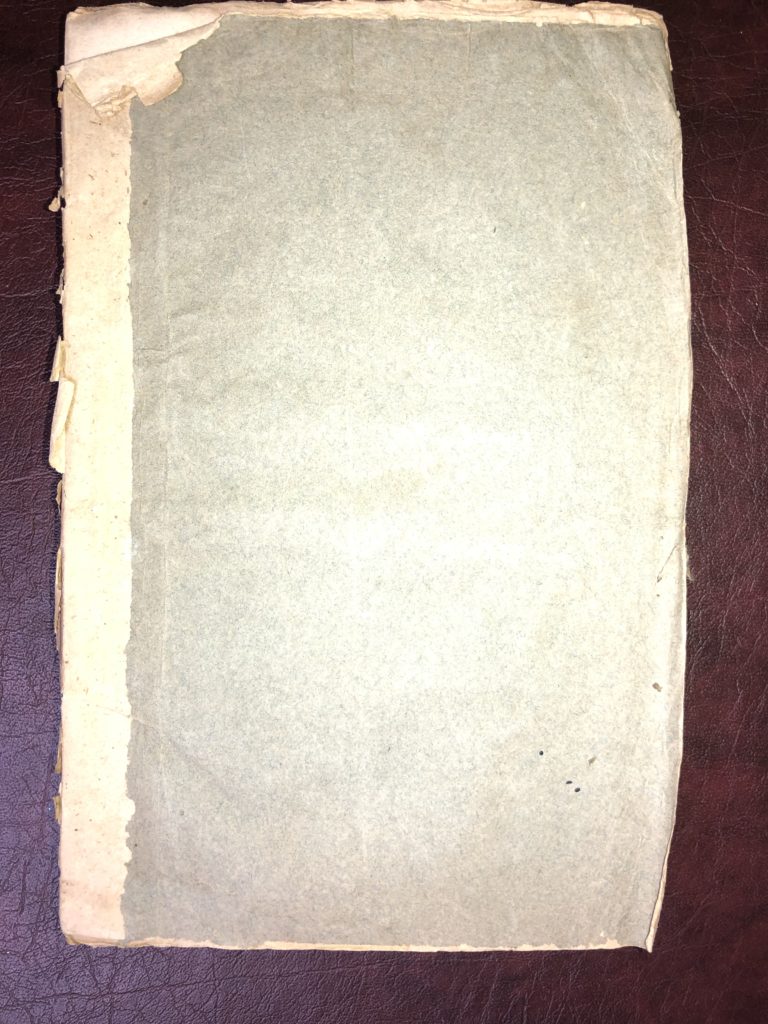

The Insurrection Act of 1807 (Chapter LXXXIV, 2nd Session, Ninth Congress)

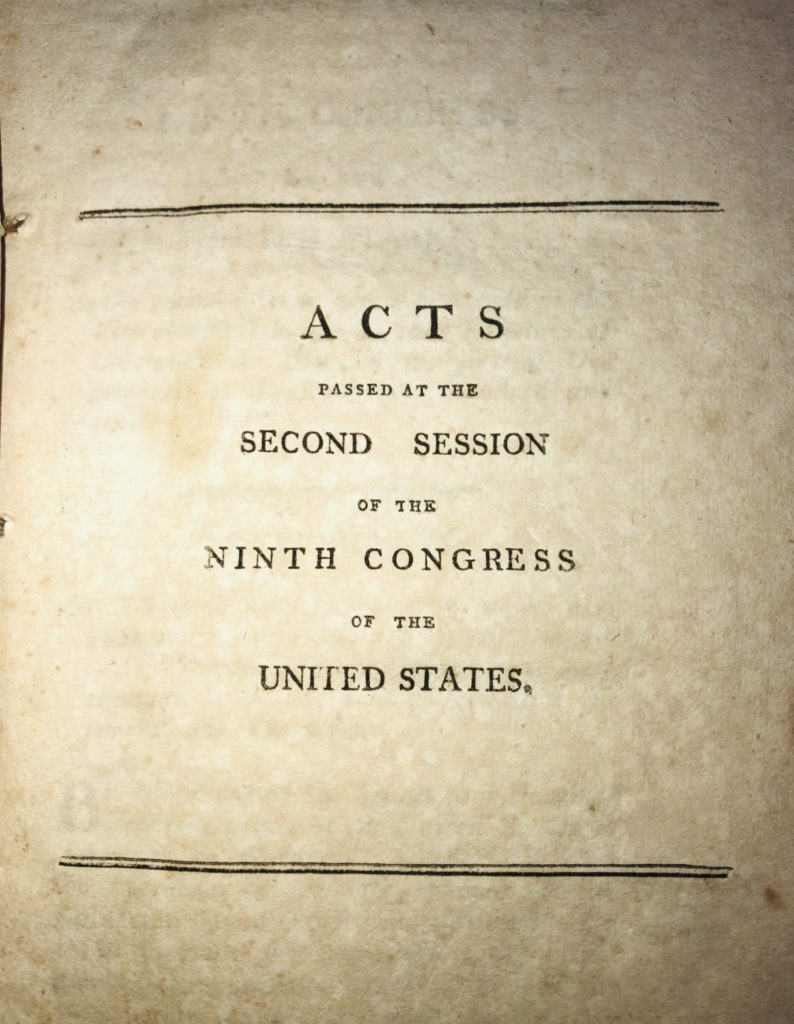

The “Insurrection Act” is a broad umbrella term for a series of statutes that date back to two laws adopted in 1792 during George Washington’s Presidency. When the law was amended by President Jefferson in 1807, the Insurrection Act label became associated with Jefferson’s amendment.

The subject of Presidential authority to deploy the military on U.S. soil has recently appeared in the news. On June 1, 2020, President Trump suggested that if the nation’s Governors did not call up the National Guard to restore order he would “deploy the United States military and quickly solve the problem for them.”

Background under Washington

Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution enumerates Congressional powers. Clause 15 provides that Congress shall have the power “To provide for calling forth the Militia to execute the Laws of the Union, suppress Insurrections and repel Invasions.”

Congress adopted two Militia Acts in 1792, the “Calling Forth Act” and the related “Uniform Militia Act.” By adopting the Calling Forth Act, Congress delegated powers to the President to call up state militias under prescribed circumstances. Click here for prior posts about the history of emergency presidential powers and the Militia Acts.

For the first several years after the Constitution was adopted, Congress avoided the controversial subject of the use of military power. Eventually, one of the worst military defeats in American history forced the Second Congress to directly and more comprehensively address the President’s power as Commander and Chief to deploy state militias.

In November of 1791 in the Battle of the Wabash River (also known as St. Clair’s Defeat and the Battle of a Thousand Slain) the U.S. military suffered a historic defeat by Chief Little Turtle during the Northwest Indian Wars. After the battle, approximately half of the entire U.S. Army was killed or wounded. These losses would not be replicated until Custer’s last stand at Little Big Horn in 1876.

Following the military defeat, President Washington forced General St. Clair to resign and the House initiated its first Congressional investigation of the executive branch. Click here for a discussion of the St. Clair investigation and the doctrine of executive privilege which was implicated in the case. In passing the Militia Acts the following year Congress was also well aware of Shay’s Rebellion in western Massachusetts (1786-1787), which was one of the motivations for the calling of the Constitutional Convention.

When originally adopted, the Militia Acts of 1792 contained an automatic sunset provision. After the law expired, Congress reenacted the Militia Act of 1795, which mirrored the expired 1792 Acts, except Congress made the President’s authority to call out the militia permanent.

1807 Amendments

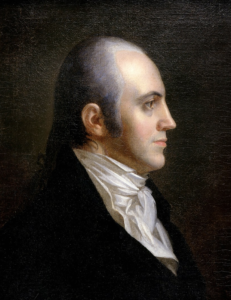

In 1806 former Vice President Aaron Burr was implicated in a conspiracy to provoke a rebellion in Spanish held territory in Louisiana and Mexico. It is believed that Burr was trying to carve out an independent nation in the Southwest that he could lead. Click here for a link to the Congressional debate over “Burr’s Conspiracy“. Burr was arrested in present day Alabama and put on trial for treason in 1807. Burr’s team of famous lawyers and founding fathers included Edmund Randolph, Charles Lee and Luther Martin. Chief Justice John Marshall tried the case before a Virginia grand jury.

During the Burr episode, President Jefferson was uncertain whether he possessed the legal authority to use federal troops to pursue Burr. At Jefferson’s request, Secretary of State James Madison reviewed the Militia Acts. In Madison’s opinion, the militia could only be used to repel foreign invasions and to suppress insurrections. According to Madison’s October 1806 legal opinion:

It does not appear that regular troops can be employed under any legal provision against insurrections—but only against expeditions having foreign countries as the object.

After Burr’s acquittal, Congress adopted the Insurrection Act of 1807. The 1807 amendments expanded the Militia Act to enhance presidential power. First, the Insurrection Act removed the word “invasion” as a precondition for the President to deploy troops. Second, the 1807 amendments authorized the President to deploy federal troops and state military against insurrections, within the United States or “any individual state or territory…” Third, the Act explicitly authorized the President to employ “land or naval” forces.

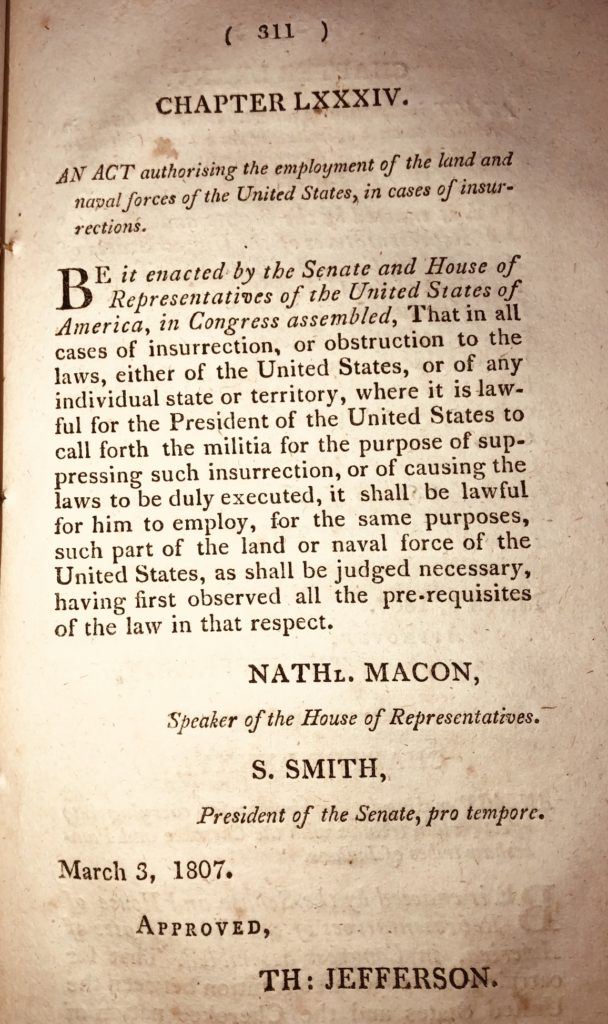

The entire Insurrection Act consists of a single paragraph, set forth below:

An Act authorizing the employment of the land and naval forces of the United States, in cases of insurrections.

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That in all cases of insurrection, or obstruction to the laws, either of the United States, or of any individual state or territory, where it is lawful for the President of the United States to call forth the militia for the purpose of suppressing such insurrection, or of causing the laws to be duly executed, it shall be lawful for him to employ, for the same purposes, such part of the land or naval force of the United States, as shall be judged necessary, having first observed all the pre-requisites of the law in that respect.

While the 1807 Act contains only a title and single sentence, the Act necessarily existed in conjunction with the earlier Militia Acts. For example, the 1807 Act authorized the President to respond to insurrection or obstruction of the laws, “where it is lawful for the President . . . to call forth the militia for the purose of suppressing such insurrection” or to “cause the laws to be duly executed.” The Act also required the President to comply wit the “all of the pre-requisites” of the law under the Militia Acts.

Under the earlier versions of the Militia Acts, in order to deploy forces, the President was required “by proclamation” to “command such insurgents to disperse, and retire peaceably to their respective abodes, within a limited time.” Click here for a discussion of the Militia Acts of 1792. The Militia Acts drew a distinction between domestic “combinations too powerful to be suppressed by the ordinary course of judicial proceedings” versus insurrections and foreign invasions. In the case of domestic lawlessness, the Milia Acts required formal notification to the President by an associate Supreme Court Justice or district judge that those opposed to the execution of the law could not be suppressed by ordinary judicial proceedings.

Use of the American Military Forces

Within a year of adoption of the Insurrection Act of 1807, Jefferson invoked the Act to respond to violations of the Embargo Act along Lake Champlain in 1808. At the time, Jefferson was trying to avoid hostilities with England and France during the Napoleonic Wars. Jefferson’s unpopular Embargo Act of 1807 was a reaction to impressment of American sailors by the British navy. Responding to a “state of insurrection” in the Lake Champlain region, Jefferson deployed military forces in northern New York and Vermont.

Prior to the adoption of the Insurrection Act of 1807, President Washington called up the military to suppress the Whiskey Rebellion in 1794. Click here for a discussion of the Whiskey Tax of 1791 and the resulting Whiskey Rebellion in western Pennsylvania.

Before deploying the militia in 1794 during the Whiskey Rebellion, President Washington obtained the following determination by Supreme Court Justice James Wilson on August 4, 1794:

Sir:—From the evidence which has been laid before me, I hereby notify to you that in the counties of Washington and Allegheny, in Pennsylvania, laws of the United States are opposed, and the execution thereof obstructed by combinations too powerful to be suppressed by the ordinary course of judicial proceedings, or by the powers vested in the Marshall of that district.

Exclusive of the Civil War, Presidents have invoked the Insurrection Act on over twenty occasions. After Jefferson, President Jackson used the Act in 1831 to suppress Nat Turner’s slave rebellion in Virginia.

In 1861, President Lincoln expanded the law to provide legal authority to wage the Civil War in a state without the permission of a governor. Following the Civil War, the law was further broadened to enable a President to enforce the civil rights protections of the 14th Amendment. Click here to a link to Lincoln’s Civil War amendments to the Insurrection Act (37th Congress, Sess. II, Ch. CCL). Section 12 of the 1862 Act authorized Lincoln to “receive into the service” of the United States “persons of African descent” to be enrolled and organized under such regulations, not inconsistent with the Constitution and laws, as the Presidet may prescribe.”

In 1871 President Grant, who was very familiar with the use of military force, sent troops into South Carolina to suppress the Ku Klux Klan during Reconstruction.

Following the 1954 Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education, Presidents Eisenhower and Kennedy repeatedly used the Insurrection Act to de-segregate Southern schools over the objection of Southern governors. In 1957, President Eisenhower famously utilized the Act in the face of opposition by Governor Orville Faubus and the Arkansas National Guard. On Eisenhower’s orders, the Army’s 101st Airborne Division formed a protective cordon around the “Little Rock Nine” as they walked to their classes at Little Rock’s Central High School.

In 1962 and 1963, President Kennedy utilized the Insurrection Act to deploy federal troops in Mississippi and Alabama to enforce civil rights laws. In 1965, President Lyndon Johnson deployed the military to protect civil rights activists on the march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama. In 1967, President Johnson sent the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions to Detroit following the outbreak of rioting. After Martin Luther King’s assassination in 1968, President Johnson re-invoked the Act.

The last time that the Insurrection Act was invoked was by President George H.W. Bush in 1992 to quell riots in Los Angeles that followed the acquittal of four police officers in the beating of Rodney King. At the time, Attorney General William Barr was serving as Attorney General in the first Bush administration. Earlier in his Presidency, Bush deployed troops to St. Croix in the U.S. Virgin Islands to control looting following Hurricane Hugo.

Following Hurricane Katrina in 2005, President George W. Bush, elected not to invoke the Insurrection Act based on opposition from local leaders. The Act was subsequently amended to clarify its use following a natural disaster. Nevertheless, faced with unanimous opposition from the governors of all 50 states, the post-Katrina amendments were repealed.

Admittedly, President Trump never identified the Insurrection Act by name. Nonetheless, after the President suggested that he would deploy military forces, Secretary of Defense Mark Esper indicated during a Pentagon press conference that he did not support using active-duty military forces to deal with the protest in American cities. According to Secretary Esper’s June 3, 2020 statement, deployment of active-duty troops in a domestic law enforcement role “should only be used as a matter of last resort and only in the most urgent and dire of situations.”

Currrent version of the law

In its current form, the Insurrection Act is codified in Title 10, Chapter 13 of the United States Code. When requested by a state, the President holds the unambiguous power to deploy troops as follows under Section 251:

10 U.S. Code § 251. Federal aid for State governments:

Whenever there is an insurrection in any State against its government, the President may, upon the request of its legislature or of its governor if the legislature cannot be convened, call into Federal service such of the militia of the other States, in the number requested by that State, and use such of the armed forces, as he considers necessary to suppress the insurrection.

The President also holds broad power to deploy the military in the face of “unlawful obstructions, combinations, assemblages or rebellion” when the “ordinary course of judicial proceedings” are otherwise inadequate. Sections 252 and 253 do not require an invitation or request from a state governor and provide as follows:

10 U.S. Code § 252 – Use of militia and armed forces to enforce Federal authority:

Whenever the President considers that unlawful obstructions, combinations, or assemblages, or rebellion against the authority of the United States, make it impracticable to enforce the laws of the United States in any State by the ordinary course of judicial proceedings, he may call into Federal service such of the militia of any State, and use such of the armed forces, as he considers necessary to enforce those laws or to suppress the rebellion.

In cases of “insurrection, domestic violence, unlawful combination, or conspiracy” Section 253 enables the President to enforce Civil Rights protections as follows:

10 U.S. Code § 253 – Interference with State and Federal law:

The President, by using the militia or the armed forces, or both, or by any other means, shall take such measures as he considers necessary to suppress, in a State, any insurrection, domestic violence, unlawful combination, or conspiracy, if it—

(1) so hinders the execution of the laws of that State, and of the United States within the State, that any part or class of its people is deprived of a right, privilege, immunity, or protection named in the Constitution and secured by law, and the constituted authorities of that State are unable, fail, or refuse to protect that right, privilege, or immunity, or to give that protection; or

(2) opposes or obstructs the execution of the laws of the United States or impedes the course of justice of those laws.

In any such situation covered by clause (1), the State shall be considered to have denied the equal protection of the laws secured by the Constitution.

In all cases, Section 254 requires the President to issue a proclamation ordering civilians to disperse prior to deploying the military as follows:

10 U.S. Code § 254 – Proclamation to disperse:

Whenever the President considers it necessary to use the militia or the armed forces under this chapter, he shall, by proclamation, immediately order the insurgents to disperse and retire peaceably to their abodes within a limited time.

Posse Comitatus Act

While the Constitution does not explicitly prohibit the use of military force against civilians, the U.S. has a long tradition of refraining from using the military for law enforcement purposes. The examples cited above are the exceptions, where the military was deployed in emergency circumstances.

The Posse Comitatus Act, 18 U.S.C. § 1385, provides as follows:

Whoever, except in cases and under circumstances expressly authorized by the Constitution or Act of Congress, willfully uses any part of the Army or Air Force as a posse comitatus or otherwise to execute the laws shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than two years, or both.

The Posse Comitatus Act makes it a crime to use the military without the express authorization of Congress. However, the Insurrection Act is itself an express authorization by Congress and thus an exception to the Posse Comitatus Act.

Since its adoption in 1877 there has never been a prosecution under the Posse Comitatus Act. The Act was adopted at the end of Reconstruction when Southern states objected to President Hay’s use of federal troops to end the Great Railroad Strike of 1877.

The original version of the Act only applied to the U.S. Army. The Act was amended in 1956 to apply to the Air Force. Subsequent amendments have yet to explicitly update the Act to apply to the Navy, Marine Corps, Coast Guard or Space Force. Nevertheless, Defense Department Policy extends the Posse Comitatus Act to the Navy and Marine Corps, but not the Coast Guard.

Additional Reading:

Lawful Military Support to Civil Authorities in Times of Crisis, Kevin Govern (Jurist.org)

Posse Comitatus Act (Northcom.mil)

The Aaron Burr Conspiracy, Walter Flavius McCaleb (1903)

The Treason Trial of Aaron Burr (famous-trials.com), Douglas Linder