THE WHISKEY TAX of 1791 – the first federal internal tax and the predictable Whiskey Rebellion:

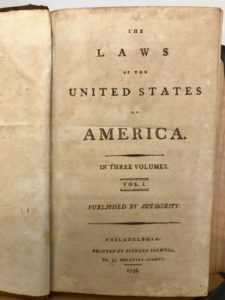

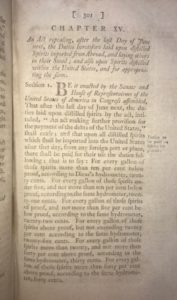

[1st Congress, 3rd Sess., Chapter 15; 1 Stat. 199-214]

The so-called Whiskey tax of 1791 was the first federal direct tax, which predictably presented the first big test for the federal government. Whiskey was the most popular distilled beverage in the 18th-century. For this reason it was referred to as the whiskey tax, although the Act applied to all spirits distilled domestically or imported.

The Whiskey Act was the third prong of Hamilton’s financial program (along with the assumption of state debt and the creation of the Bank of the United States). The Act was based on Congress’ new constitutional authority to “lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises.”

The Act created fourteen new revenue taxing districts corresponding to the fourteen states. The broad and intrusive tax applied to distilleries in “any city, town, or village.” Section 17 of the Act prohibited removal of spirits from the distillery until the tax was paid. Section 19 of the Act provided that each cask was required to be numbered and labeled with the name of the distillery, owner, location, quantity and proof.

The tax was also unpopular because it required payment in cash at a time when whiskey itself was often a monetary unit westerners used to pay for their goods and services. Western farmers commonly distilled their crops rather than transporting bulky crops long distances across the Appalachian and Allegheny Mountains. For this reason the tax proved to be less burdensome for larger, eastern producers who were located closer to large markets. Moreover the cost per gallon was nine cents per gallon for smaller producers whereas larger suppliers were eligible for volume and pre-payment tax discounts which lowered the tax to six cents per gallon.

Background: Secretary of Treasury Alexander Hamilton explained that the tax was needed to diversify federal revenue which was otherwise entirely dependent on tariffs/custom duties (taxes on imports). Hamilton reported to Congress in December of 1790 that tariffs could not reasonably be raised any higher, but he needed an additional source of revenue. (Click here for a link to Hamilton’s Report on the Public Credit.) Balancing the costs and benefits of imposing this new tax, Hamilton convinced Washington and Congress to adopt the controversial measure, which would spread the pain of taxation more evenly around the country than import tariffs which fell on coastal merchants. Washington had initially been opposed to the proposal. In 1791 he traveled to Virginia and Pennsylvania to personally speak to local officials who supported the idea.

Hamilton had to weigh the risks of provoking political opposition to his need as Treasury Secretary to reliably service the federal debt and inevitable new spending demands on the federal government. Hamilton knew that direct taxation and the Stamp Act had given rise to the Revolution. Accordingly, Hamilton rejected a direct tax on people or households. Given the strength of agricultural interests and land speculators, Hamilton also rejected a land tax as politically unfeasible. Yet, as Hamilton had noted in Federalist 12, a whiskey tax had the collateral social benefits of increasing sobriety. In fact, James Madison supported the tax on this basis, acknowledging that increased sobriety might help “prevent disease and untimely deaths.” Philadelphia’s College of Physicians also endorsed the sin tax on the expectation that the nation’s morals would improve if higher whiskey prices reduced consumption.

In addition to raising revenue, Hamilton was aware of the additional political advantages of the tax. He admitted to Washington that an ulterior motive was to lay hold to this revenue source before the states did. The necessary expansion of federal authority to enforce the tax could be justified since Congress had recently agreed to Hamilton’s proposal to assume state debts. (Click here for a link to a discussion of the debt compromise).

To enforce the Act, Hamilton had specified sweeping enforcement powers for the required federal tax collectors and inspectors. In his Report on the Public Credit, Hamilton supported unannounced inspections at any hour, including entry into homes and warehouses to confiscate hidden domestic stills. After the tax was adopted, Hamilton issued comprehensive Treasury rules for his inspectors, seeking detailed weekly reporting on distilleries, capacity, locations, and ownership with twice daily inspections.

Whiskey Rebellion: As predicted, the Whiskey tax proved unpopular in the remote regions of Western Pennsylvania where homemade whiskey production was ingrained in the local culture and economy. During the bitter Congressional debates, it was no secret that the Pennsylvania legislature has been unable to enforce excise taxes on its lawless mountainous countryside.

When the Act was adopted residents of Western Pennsylvania were already dissatisfied with the army’s unsuccessful efforts to defeat Chief Little Turtle and the Miami Confederacy in the Ohio valley.

Many westerners refused to pay the tax. Tax collectors were increasingly ambushed or humiliated, with some being harassed, threatened, and/or tarred and feathered. In 1792, President Washington condemned interference with the “operation of the laws of the United States.”

Opposition to the Whiskey tax broke out into open rebellion in July of 1794 when farmers in Western Pennsylvania rioted. Three rioters were killed and several members of responding local militia were injured. About 7,000 rebels met on August 1 to plot the destruction of Pittsburg, but decided not to risk confronting the heavy guns of the fort which guarded the town.

Notwithstanding Washington’s appeals for a peaceful resolution, unrest continued in the western frontiers of Pennsylvania, Maryland and Virginia. On August 7, 1794, Washington called for the rebels to disperse and return to their homes by September 1.

Mindful of Shay’s Rebellion, Washington decided to take decisive action. He invoked the Militia Act of 1792 under which the President was authorized to use State militia. Click here for a link to the Act to Authorize the President to Call Out and Station a Corps of Militia in the Four Western Counties of Pennsylvania, for a Limited Time.

Mindful of Shay’s Rebellion, Washington decided to take decisive action. He invoked the Militia Act of 1792 under which the President was authorized to use State militia. Click here for a link to the Act to Authorize the President to Call Out and Station a Corps of Militia in the Four Western Counties of Pennsylvania, for a Limited Time.

Washington assembled approximately 13,000 militiamen from New Jersey, Maryland and Virginia and marched westward in October of 1794. When Washington and his troops arrived they faced little resistance. They arrested 150 rebels, most of whom were released due to lack of evidence. Two rebels were convicted of treason but later pardoned by Washington on November 2, 1795. The Whiskey Rebellion would prove to be the largest rebellion of its kind – and the largest use of military force against a domestic uprising – until the Civil War.

In his sixth State of the Union address President Washington summarized the Whiskey Rebellion and his successful response as follows:

“During the session of the year 1790 it was expedient to exercise the legislative power granted by the Constitution of the United States “to lay and collect excises”. In a majority of the States scarcely an objection was heard to this mode of taxation. In some, indeed, alarms were at first conceived, until they were banished by reason and patriotism. In the four western counties of Pennsylvania a prejudice, fostered and imbittered by the artifice of men who labored for an ascendency over the will of others by the guidance of their passions, produced symptoms of riot and violence…..

Thus the painful alternative could not be discarded. I ordered the militia to march, after once more admonishing the insurgents in my proclamation of the 25th of September last. It was a task too difficult to ascertain with precision the lowest degree of force competent to the quelling of the insurrection. From a respect, indeed, to economy and the ease of my fellow citizens belonging to the militia, it would have gratified me to accomplish such an estimate. My very reluctance to ascribe too much importance to the opposition, had its extent been accurately seen, would have been a decided inducement to the smallest efficient numbers. In this uncertainty, therefore, I put into motion 15K men, as being an army which, according to all human calculation, would be prompt and adequate in every view, and might, perhaps, by rendering resistance desperate, prevent the effusion of blood. Quotas had been assigned to the States of New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia, the governor of Pennsylvania having declared on this occasion an opinion which justified a requisition to the other States.” (Click here for a link to the full State of the Union address.)

In his seventh State of the Union address Washington explained his decision to issue the first pardon in U.S. history. The first draft of the address was written by Hamilton and John Jay and provides:

“The misled have abandoned their errors and pay the respect to our Constitution and laws which is due from good citizens to the public authorities of the society. These circumstances have induced me to pardon generally the offenders here referred to, and to extend forgiveness to those who had been adjudged to capital punishment. For though I shall always think it a sacred duty to exercise with firmness and energy the constitutional powers with which I am vested, yet it appears to me no less consistent with the public good than it is with my personal feelings to mingle in the operations of Government every degree of moderation and tenderness which the national justice, dignity, and safety may permit.” (Click here for a link to the full State of the Union.)

The Whiskey Act remained in effect until 1802 when President Thomas Jefferson repealed it. The Whiskey Rebellion was the first serious challenge to federal authority in the new United States. Yet, the successful assertion of federal power reinforced Hamilton’s position that the new government had the right to levy and enforce wide reaching and unpopular taxes. Washington’s willingness to use force and enforce the law demonstrated that the national government would not allow violent resistance to go unchecked.

Click here for a link to John Adams’ copy of the Whiskey Act:

Click here for the full text of the Act:

Further reading:

Washington’s 6th State of the Union Address (StateoftheUnionHistory.com)

Please let me know if you’re looking for a writer for your blog.

You have some really good posts and I believe I would be a

good asset. If you ever want to take some of the load

off, I’d love to write some content for your blog in exchange for a link back to mine.

Please send me an email if interested. Many thanks!

Cecilia,

Thanks for your inquiry. I’d like to check you your blog. What is the subject? Feel free to reply with a link.

Best, Adam