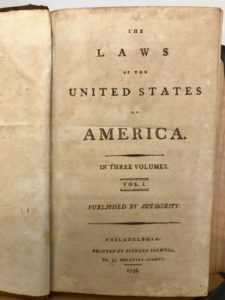

Copyright Act of 1790 (First Copyright Act adopted by the First Congress)

[1st Congress, 2nd Sess., Chapter XV; Stat. 124-126] (May 31, 1790)

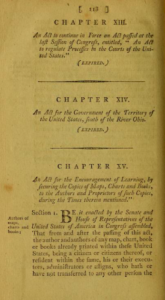

“An Act for the encouragement of learning, by securing the copies of maps, Charts, and books, to the authors and proprietors of such copies, during the times therein mentioned.” (Click here for a link to the full text of the Act)

During the drafting of the Constitution, James Madison and Charles Pinckney proposed that the new federal government should have the power to issue copyrights. The founders agreed and Article 1, Sect. 8, cl. 8 of the Constitution granted Congress the power “[t]o promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.”

It made sense to have one national law on the subject, rather than overlapping – and potentially conflicting – state copyright laws. All states except for Delaware had adopted their own copyright laws during the Article of Confederation period. Eighty years earlier, in 1710, England had adopted the first copyright law known as the Statute of Anne. (Click here for a link to the Statute of Anne, 8 Ann. c. 19)

Naturally, the first Congress looked to the Statute of Anne as a model. For example, the Statute of Anne permitted 14 years of copyright protection, with the right to renew for a second 14 year term. The Copyright Act of 1790 applied these exact timeframes copied from England. Yet, Congress purposely expanded the materials eligible for copyright under U.S. law to include “maps, charts and books” while the Statute of Anne only protected “books and other writings.”

When compared to modern copyright law, the Copyright Act of 1790 was a relatively concise seven paragraphs. The Act provided as follows:

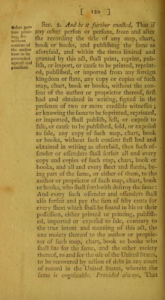

· authors “shall have the sole right and liberty of printing, reprinting, publishing and vending such map, chart, book or books, for the term of fourteen years from the recording the title thereof in the clerk’s office, as is herein after directed”;

· allows a right to renew for a second 14 year term, provided the author re-records the copyright within 6 months before expiration;

· only protects American citizens or residents, but prohibits the importation of copies of copyrighted material without permission by the owner;

· provides for a penalty of “50 cents per sheet” for violations; and

· required that enforcement suits be commenced within one year after the cause of action arises.

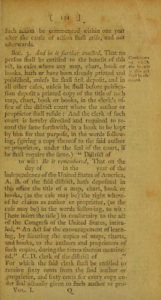

The Act contained several procedural requirements to record a copyright, including:

· depositing the title page of the work with the clerk’s office at the local U.S. district court;

· requiring payment of 60 cents to the clerk, who was required to record the copyright and provide a written certification;

· sending a copy of the work within six months of publication to the U.S. Secretary of State (which was later changed to the Library of Congress); and

· publishing notice of the copyright within two months in one or more newspapers in the United States, for the space of four weeks.

Background: The Copyright Act of 1790 was adopted during the second session of the First Congress. In his joint address to Congress at the start of the Second Session on January 8, 1790, President Washington indicated that “there is nothing that can better deserve your patronage than the promotion of science and literature.” Copyright petitions had been submitted during the First Session, which were referred for further study to early committees. (Click here for a link to the House Journal entry discussing the petitions)

Washington explained as follows:

The advancement of agriculture, commerce, and manufactures, by all proper means, will not, I trust, need recommendation; but I cannot forbear intimating to you the expediency of giving effectual encouragement, as well to the introduction of new and useful inventions from abroad, as to the exertions of skill and genius in producing them at home; and of facilitating the intercourse between the distant parts of our country by a due attention to the post-office and post roads.

Nor am I less persuaded, that you will agree with me in opinion, that there is nothing which can better deserve your patronage, than the promotion of science and literature. Knowledge is, in every country, the surest basis of public happiness.

(Click here for a link to Washington’s full address recorded in the Senate Journal, 1st Cong., 2nd sess., January 8, 1790, p. 103)

The Senate’s reply to President Washington observed that “Literature and Science are essential to the preservation of a free Constitution: the measures of Government should, therefore, be calculated to strengthen the confidence that is due to that important truth.” Similarly, the House’s reply agreed that “the promotion of science and literature will contribute to the security of free Government; in the progress of our deliberations we shall not lose sight of objects so worthy of our regard.”

Subsequent history: Later amendments extended copyright protections to music, art and other forms of creative expression. The International Copyright Act of 1891 expanded protections to cover foreign copyright holders. Prior to 1891, foreign authors, including Charles Dickens, complained about cheap American knockoff publications.

Prior to the Civil War, Harriet Beecher Stowe sued to recover damages for an unauthorized German translation of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. The United States Supreme Court ruled that there was no infringement since copyright owners did not hold the exclusive right to translate their works. Following the case of Stowe v. Thompson (1853) Congress revised the law.

The Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act extended copyright length from the life of the author plus 50 years, to the life of the author plus 70 years (corporate protections were extended from 75 to 95 years).

Today’s copyright laws are codified in Chapters 1 through 8 and 10 through 12 of title 17 of the United States Code.

Additional reading:

Copyright timeline and amendments (Library of Congress)

Copyright records 1790 – 1810 (Library of Congress)

Click here to review John Adams’ copy of the Laws of the United States