The infamous Manhattan Well Murder case of 1800

On December 22, 1799, Elma Sands disappeared. When she went out for the night, her family understood that she was with her fiancee, Levi Weeks. Ten days later, on January 2, her body was discovered at the bottom of a well at the outskirts of Manhattan, near present day SOHO. The resulting “Manhattan Well” murder mystery riveted New York.

Elma Sands was an attractive young lady from a respectable Quaker family. Historian Ron Chernow describes how public opinion “assumed the vengeful mood of a witch-hunt” against Levi Weeks, a twenty-three year old carpenter who lived in the same boarding house with Elma. Ultimately, the marathon trial would require testimony from fifty-five witnesses. It is thus not surprising that the case, the first American trial to become a media circus, was also the first fully transcribed murder trial in American history.

On the surface, the case might appear to be a typical big city murder. Yet, the cause celebre became the first sensationalized, celebrity murder case of its kind. Levi Weeks and his wealthy brother assembled arguably the most distinguished team of lawyers in American history. This post tells the story of the original legal “dream team” that defended Levi Weeks: Alexander Hamilton (the first Treasury Secretary and founder of the Federalist party), Aaron Burr (a future Vice President and rival of Hamilton’s) and Henry Brockholst Livingston (a future Supreme Court Justice).

Adding to the case’s significance was the fact that 1800 was a historic presidential election year. Hamilton and Burr were engaged in a major political battle to determine if New York would continue to support President John Adams and Hamilton’s Federalist party, or whether the state would migrate to support Jefferson and the emerging Democratic-Republican party. By the end of the year, following the “Revolution of 1800”, Jefferson would be elected President. Aaron Burr, Hamilton’s political rival, would be Vice President.

Today, more than 200 years later, it is possible to retell the story of the Levi Weeks case in remarkable detail. Among other primary sources, this post uses the trial transcript, contemporaneous newspaper articles, the diary of Elizabeth Bleecker, and several excellent books about the Levi Weeks case.

This post, People v. Weeks (Part 1), will provide background about the case. People v. Weeks (Part 2) will tell the story of the trial. Part 3 will provide a post script about the trial’s aftermath, including its role in popular culture. For example, the Weeks trial provided fodder for the writings of Washington Irving and Edgar Allan Poe. Today, the trial of Levi Weeks is featured in Non-Stop, the last song of Act 1 of the Hamilton musical by Lin-Manuel Miranda.

Background: In 1800 Alexander Hamilton was one of the most highly regarded and sought after lawyers in the country. Ordinarily he did not represent criminal defendants. His busy law practice was primarily focused on complex commercial matters. At the time, Hamilton was also serving as the Inspector General of the United States military and was focused on preparing the nation for a potential war with France. If General Hamilton wasn’t busy enough, he was also the leader of the Federalist party. Hamilton, however, would take important cases on a pro bono basis when he felt that justice required his involvement.

According to Ron Chernow, “[s]uch a case arose in the spring of 1800 when he thought a likable young carpenter named Levi Weeks was being unjustly accused of murder. As in the postwar cases, Hamilton was disturbed whenever public opinion howled for bloody revenge.”

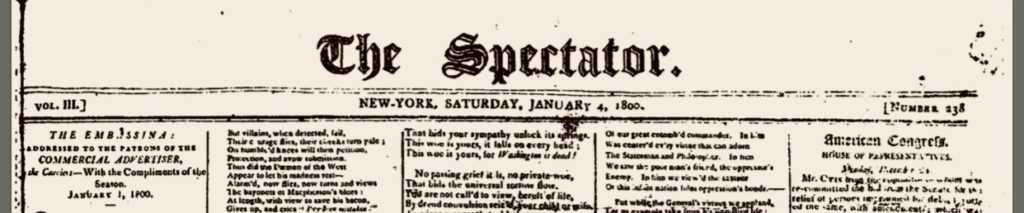

Elma Sands went missing on December 22. Elma’s full legal name was Guliana Elmore Sands, but she was also known to friends and family as Elma or Juliana. On January 4, 1800 The New York Spectator reported that:

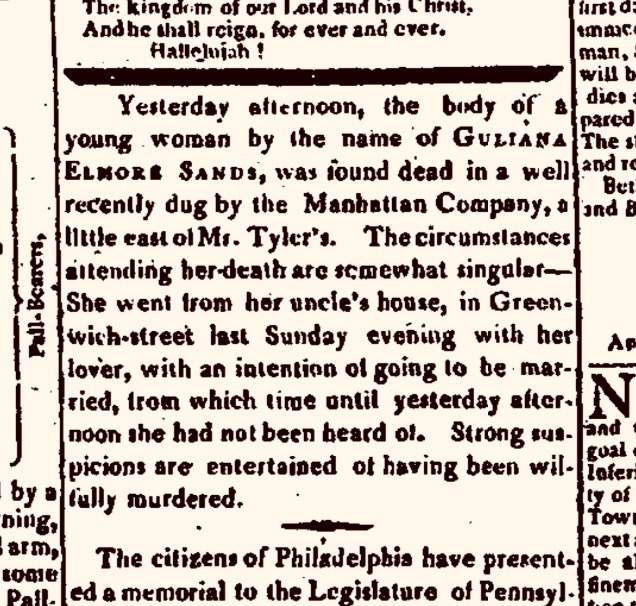

Yesterday afternoon, the body of a young woman by the name of Guliana Elmore Sands, was found dead in a well recently dug by the Manhattan Company…The circumstances attending her death are somewhat singular – She went from her uncle’s house, in Greenwich street last Sunday evening with her lover, with an intention of going to be married, from which time until yesterday afternoon she had not been heard of. Strong suspicions are entertained of having been willfully murdered.

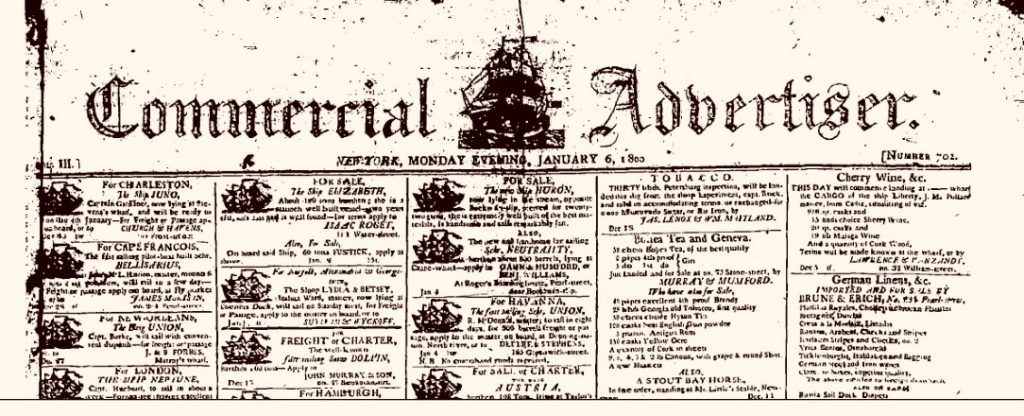

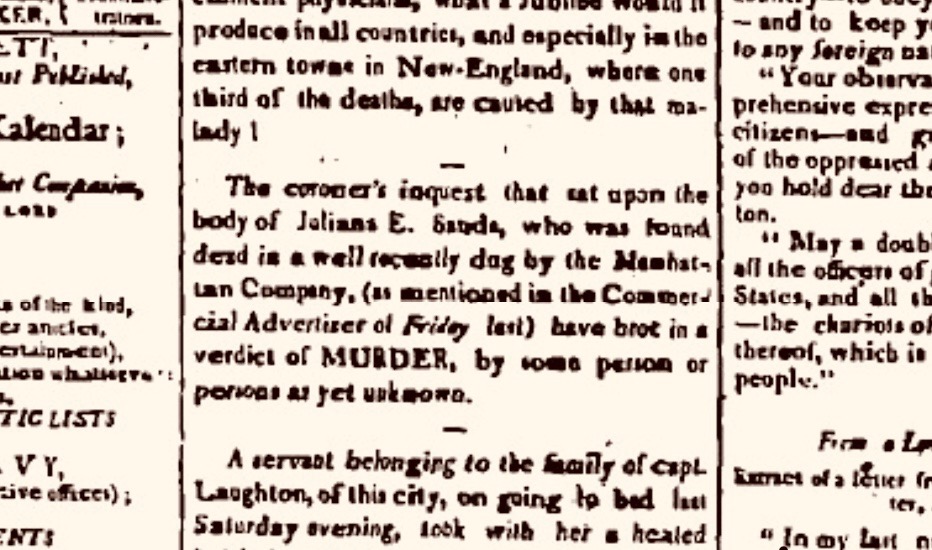

Two days later, the New York Commercial Advertiser revealed Elma’s cause of death. According to the coroner’s inquest, Elma was murdered “by some person or persons yet unknown.” When Levi was asked to identify the body, he seemingly knew were Elma had been found, inquiring whether she had been found in the recently dug Manhattan Company well. He was arrested pending trial, with public opinion convinced that Levi was to blame.

Large crowds came to view Elma prior to her funeral. Elma lived with her aunt and uncle, Catherine and Elias Ring, who owned and operated a boarding house at 108 Greenwich Street, near Greene and Spring Streets. Also living in the boarding house was Elma’s cousin, Hope Sands, and several boarders, including Levi Weeks.

It was common practice for Quakers to display the body of a deceased family member in the parlor for viewing prior to burial. As the crowds increased, Elma’s grieving family decided that the frozen streets of New York would be their parlor, so that all visitors could see Elma and the bruises on her neck and chest. Her decaying body was thus laid out for public view in an open casket guarded by friends and public officials for 3 days, in a previously unimaginable scene witnessed by untold numbers of outraged New Yorkers.

At the same time, newspaper and handbills incited additional public outrage, accusing Levi Weeks of impregnating Elma prior to the murder. Or perhaps, Levi opted to kill her after learning that she was pregnant? While the body was on display, and for the weeks leading up to the trial, one voice in particular actively spread the news that Levi Weeks was the murderer. Richard Croucher, one of the other residents of the Ring boarding house would play a prominent and unexpected role at the trial, which would begin on March 31, 1800.

The indictment charged that Weeks, “not having fear of God before his eyes, but being moved and seduced by the instigation of the devil, on the 22d day of December….with force and arms…feloniously, willfully, and of his malice aforethought, did make an assault, …strike, beat and kick, with his hands and feet, in and upon the head, breast, back, belly, sides and other parts of the body” before casting Gulielma Sands into a certain well.”

In an effort to reverse the tide of pre-trial hostility against their client, Levi’s lawyers warned that the public should not rush to judgment. On January 9, 1800, the following admonition was published in the New York Daily Advertiser, reminding readers that Levi was a “sober, industrious, amiable” young man. The article also offered a competing theory for Elma’s death, that she suffered from “melancholy” and may have committed suicide:

The public are desired to suspend their opinion respecting the cause of the death of a young woman whose body was lately found in a well,” the editorial suggested so that the prisoner “may be condemned or acquitted by the free and unprejudiced voice of an impartial jury”.

Yet, here had been “horrid imputations” cast upon “a certain young man”—but he was “sober, industrious, amiable.…He has no conceivable temptation to perform such an atrocious action.” The editorial also challenged that a crime had been committed at all as Elma “had several times been heard to utter expressions of melancholy, and throw out threats of self-destruction, particularly the afternoon before.”

The previous year, New York had suffered through a deadly Yellow Fever outbreak. Then in mid-December, a week before Elma’s disappearance, President George Washington passed away. In this climate, New Yorkers reported tales of ghosts, goblins and dancing devils being seen about the City. And of course, Levi Weeks was surely a living monster.

As described by historian and Senator, Henry Cabot Lodge in 1916, Elma’s disappearance produced “a great deal of excitement, which rose to fever heat after the finding of the body.” The public understood that Weeks was guilty as “he had been the girl’s lover, very intimate with her, as appeared by the testimony, where it was also in evidence that he was not the only fortunate person in this respect.”

“The case also gives some glimpses of society a hundred years ago which afford queer contrasts with the manners and habits of the present time.” Lodge was particularly impressed by the legends and mythology that grew out of the case. As described by Lodge, different biographers would attribute different trial lore to either Hamilton or Burr, depending on who they were writing about. The Democracy of the Constitution and Other Addresses and Essays (1916).

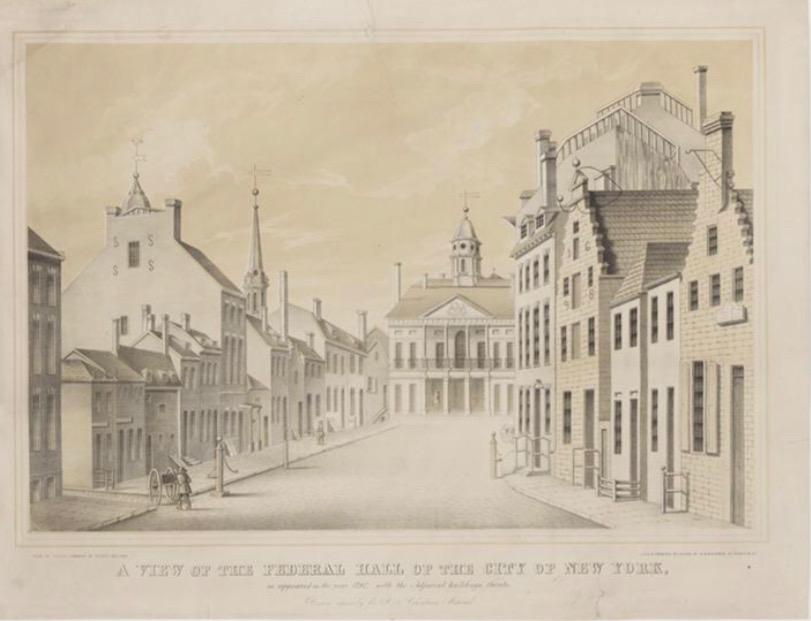

The case would be tried at New York’s old City Hall, located at the north-east corner of Wall and Nassau Streets. Also known as Federal Hall, Congress met in the same building in 1789, which served as the nation’s first capital. George Washington was sworn in on the second floor balcony where the jury would be sequestered overnight during the Weeks trial.

The story of the trial will be continued in The People v. Weeks (Part 2).

Additional reading:

Report of the Trial of Levi Weeks, on an Indictment for the Murder of Gulielma Sands, William Coleman (1800)

Estelle Fox Kleiger, The Trial of Levi Weeks or The Manhattan Well Mystery (1989)

Julius Goebel, Jr., The Law Practice of Alexander Hamilton (1964)

Gazette of the United States, April 4, 1800

Liva Baker, The Defense of Levi Weeks, ABA Journal (June, 1977)