The aftermath of the trial of the century

This post, The People v. Levi Weeks (Part 3), provides the post-script to one of the most notorious murder cases in American history. Following the discovery of Elma Sands’ body in a Manhattan well on January 2, 1800, the public clamored for revenge against her lover, Levi Weeks. The first post, The People v. Levi Weeks (Part 1), introduced Elma Sands, the victim, and her fiancee, Levi Weeks. Part 1 also provided background about the turn of the 19th Century, including Washington’s death in December of 1799, a week prior to Elma’s disappearance. The new year would also witness the growing political shift away from Hamilton’s Federalist party to Jefferson and Burr’s Democratic-Republican party.

The second post, The People v. Levi Weeks (Part 2) tells the story of the marathon criminal trial. Fifty-five witnesses testified in the case, which was likely the longest murder trial thus far in American history. It was also the first trial to be fully transcribed. Despite a mountain of evidence, expert cross examination exposed the weaknesses in the prosecution’s largely circumstantial case. Although Levi Weeks had already been convicted in the court of public opinion, Alexander Hamilton, Aaron Burr and future Supreme Court Justice, Henry Brockholst Livingston convinced a Manhattan jury to acquit their client, after only five minutes of jury deliberations.

This post, The People v. Levi Weeks (Part 3) completes the story, post-trial. In some respects, the story of the lawyers, judges and witnesses in the case is arguably as compelling as the trial itself. Part 3 also explores the role of the Weeks case in popular culture. In other words, the drama of the case lives on, as viewed through the work of literary and artistic giants, Washington Irving, Edgar Allan Poe and Lin-Manuel Miranda.

Post script: Many of the participants in the Levi Weeks court drama continued in the public spotlight after the trial. Others, including Alexander Hamilton, his son Philip, and Judge Lansing, tragically lost their lives, adding to the lore of the case.

Of course, Hamilton and Burr appeared together in the century’s next great crime story, their fatal duel in 1804. Attorney Brockholst Livingston also killed a man in a duel, James Jones, but Livingston would nonetheless be appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court by President Jefferson. Unlike Burr, who was never forgiven for the death of Hamilton, Livingston’s duel did not impact his career. It is said, however, that the death left Livingston under a cloud of “gloom from which he never recovered.”

John Lansing (the Judge)

During the Revolutionary War, John Lansing, Jr., served as a military secretary for General Philip Schuyler (Alexander Hamilton’s future father-in-law). After the War Lansing served in both the New York Assembly and the Congress of the Confederation. Lansing knew Alexander Hamilton well, having worked together as delegates to the Constitutional Convention in 1787. Unlike Hamilton, Lansing departed the Convention with New York’s other delegate, believing that the proposed Constitution exceeded the Convention’s mandate.

At the time of the Weeks trial, Lansing was the Chief Judge of the New York Supreme Court (the state’s trial level court with general jurisdiction). A year after the trial he would be appointed to the New York Court of Chancery (the state’s highest court which is now the New York Court of Appeal). While on the court he served as Chancellor of the State of New York, the highest judicial position in New York at the time.

Catherine Rings’ curse

Elma Sands’ family was not pleased with Levi’s acquittal. At the conclusion of the trial, after the jury reached its verdict, legend holds that a famous curse was uttered by Catherine Ring, Elma Sands’ aunt.

As described by Allan McClain Hamilton, Hamilton’s grandson:

Mrs. Ring’s anger and violence when the verdict was brought in were intense. Shaking her fist in Hamilton’s face she said, “If thee dies a natural death I shall think there is no justice in heaven.” In this connection it is a curious fact that both Chief Justice Lansing and Hamilton died as she had predicted. The former was not seen alive after he left his hotel one day, in 1829, to reach the Albany boat, and his body was never found.

Allan McClain Hamilton, The Intimate Life of Alexander Hamilton (1910). To this day, Lansing’s disappearance remains a complete mystery.

Levi Weeks (the defendant)

Although Levi Weeks was acquitted, he could not escape public ignominy in New York. Given all of the publicity and stigma, it is not surprising that he would have wanted a fresh start. Within two years he would leave the state to ultimately prosper as a successful builder and architect in Natchez, Mississippi. He had several children but died at the relatively young age of 43. A house he designed, the Auburn Mansion, has been designated as a National Historic Landmark and is picture below.

“Mad Croucher” (the actual murderer?)

The most infamous figure in the case was prosecution witness Richard David Croucher, an Englishman known as “Mad Croucher.” On the eve of the trial Croucher married an American widow with a 13-year-old daughter. According to historian Henry Lodge, Croucher was later convicted of raping his thirteen-year-old step daughter at the Ring boarding house. During Croucher’s rape trial, she testified that she feared that she would suffer Elma Sands’ fate if she reported the crime.

Remarkably, due to his questionable sanity, Croucher was shown mercy and pardoned on the condition that he leave the state. Croucher moved to Virginia where his crime spree continued. He ultimately fled to his native country, England, where he was executed “for some heinous crime” that involved strangling a woman.

The Manhattan Company Well and Lispenard’s Meadow

The Manhattan Company well where Elma Sands’ body was found was located in the northeast corner of Lispenard’s Meadow, a marsh on the then northern periphery of New York City. Today the former meadow is better known as the SoHo/TriBeCa neighborhoods in southern Manhattan. The Meadow contained three creeks. After the marsh was drained, its memory lives on with the appropriately named Spring and Canal streets. Indeed, the well can be found today in a basement located at 129 Spring Street.

At the time of the trial in March of 1800 the famous well had recently been constructed by the Manhattan Company. Perhaps one of the reasons that Aaron Burr agreed to take the Wells case was because he was one of the founders of the Manhattan Company that built the well. Today, this would raise conflict of interest issues, but the law was less well developed at the time.

When he chartered the Manhattan Company, Burr’s primary motivation was not actually supplying water to the city. Rather, Burr slipped a provision into the Company’s charter allowing it to make loans with its excess capital. Thus, the Manhattan Company was actually a defacto bank approved by the New York Legislative that Burr and his fellow New York Democrat-Republicans could use to compete with Hamilton’s Bank of New York. The only other bank in New York City at the time was the First Bank of the United States. Of course, both of these banks were dominated by Hamilton and his Federalists allies. For a detailed discussion of the Manhattan Company, see Brian Philllips Murphy’s A very convenient instrument’: The Manhattan Company, Aaron Burr, and the Election of 1800

Eventually, Burr’s bank would become Chase Manhattan Bank. Through subsequent mergers and acquisitions it is now J.P. Morgan Chase, the world’s largest bank. Alexander Hamilton’s competing Bank of New York continues making loans today as BNY Melon. In 1894, Alexander Hamilton’s great grandson, William Pierson Hamilton, married Juliet Pierpont Morgan, the daughter of J.P. Morgan. In other words, in an ironic twist, Hamilton family descendants became part owners of the bank which would eventually acquire Burr’s Chase Manhattan Bank.

Attorney Henry Brockhurst Livingston

Of the three members of the “dream team,” lawyer Henry Brockhurst Livingston is the least well known today. Nevertheless, he had impeccable Revolutionary War credentials and would ultimately have the longest legal career of all the high powered lawyers in the Levi Weeks case.

Brockholst was the son of New Jersey Governor and founding father, William Livingston. During the Revolutionary War, 19 year old Brockholst joined the Continental Army and served on the staff of General Philip Schuyler (Hamilton’s father in law) and as as aide-de-camp to Major-General Benedict Arnold and General St. Clair during the siege of Fort Ticonderoga and the Battle of Saratoga. Brockholst’s older sister, Sara Livingston, married American diplomat and Supreme Court Chief Justice, John Jay.

When John Jay was appointed Minister to France in 1779, Brockholst served as his brother-in-law’s private secretary during the diplomatic mission to Spain to obtain support for the American war effort. On his trip back from Spain in 1782 Brockholst’s ship was intercepted and he was captured by the British. Brockholst was paroled as the war wound down in 1783 (with the Treaty of Paris being negotiated by John Jay, Benjamin Franklin and John Adams).

After the Revolutionary War Hamilton, Burr and Brockholst Livingston worked together in the emerging New York bar. Most famously, Hamilton and Livingston teamed up to successfully litigate the important case of Rutgers v. Waddington (which is discussed in another post). The Rutgers case was the first to establish the principle that state laws in conflict with a United States treaty or federal law are void. The decision was an early precedent for the doctrine of judicial review, which would be established by Chief Justice Marshall in the case of Marbury v. Madison in 1803.

In 1802, Livingston was appointed to the New York Supreme Court. In 1806 he was elevated to the U.S. Supreme Court by President Thomas Jefferson to serve as a counter weight to Chief Justice Marshall. Livingston’s famous cases included McCulloch v. Maryland (1819), where a unanimous court recognized the supremacy the Constitution over state efforts to tax (and potentially destroy) Hamilton’s Bank of the United States.

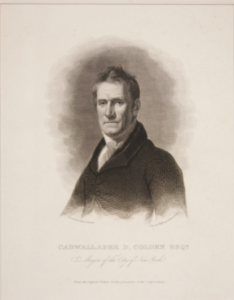

Attorney Cadwallader David Colden (the Prosecutor)

The prosecutor in the Weeks case, thirty-two year old Cadwallader David Colden, was eventually elected the 54th mayor of New York City in 1818. Colden also served as the president of the New York Manumission Society, which was founded by John Jay and Alexander Hamilton in 1785 to promote the abolition of slavery in New York. In this capacity he oversaw the rebuilding of the Society’s African Free School for freed slaves. Colden also worked with John Jay’s sons, Peter A. Jay and William Jay to convince the New York legislature to set July 4, 1827 as the date for the final abolition of slavery in New York.

Colden successfully advocated for the construction of the Erie Canal, the biggest infrastructure program of its day. Colden was also active in promoting the New York public school system and was a leading member of the New York Society for the Prevention of Pauperism. Colden published two books during his lifetime, The Life of Robert Fulton (1817) and Memoir at the Celebration of the Completion of the New York Canals (1825).

Aaron Burr

The arc of Aaron Burr’s life is beyond the scope of this post. Of course, shortly after the trial he would be elected Vice President. The fatal duel with Hamilton would end their rivalry in 1804. Burr fled to Europe after he was acquitted in an unrelated treason trial. According to his diaries, Burr was so broke in Paris that he lived in 10 x 10 rented room. He observed the one virtue of his circumstances was that “I can sit in my chair and reach every and anything that I possess.”

When Burr later returned to New York after a decade in Europe, he was denied a pension for his Revolutionary War service. He was forced to resume working as a lawyer and eventually became highly successful as one of the first specialists in divorce/family law (one of the few fields that was open to him based on his reputation). Burr died in 1836, outliving Hamilton by 32 years.

William Coleman (the court reporter)

The court clerk, William Coleman, published the extensive court transcript of the Weeks trial. Coleman has been described as “a master of short hand.” His detailed transcript included, verbatim, attorney questions and the corresponding witness answers, along with the argument by counsel and the judge’s instructions. In transcribing the trial, Coleman used the abstract geometric shapes of Byrom’s New Universal Shorthand, which interestingly was initially developed as a secret code to conceal (not reveal) communications.

One of Coleman’s political enemies later admitted that his trial transcript “is everywhere admired for its arrangement, perspicuity, and the soundness of judgment it displays.” The Evening Post: A Century of Journalism, Allan Nevins (1922). Coleman would become a protege of Alexander Hamilton, who named Coleman as the first editor of Hamilton’s newspaper, the New York Evening Post. Hamilton founded the paper in 1801 after he was dismayed by Jefferson’s election to the presidency. In this role, at the head of the New York Evening Post, Coleman brilliantly stepped into Hamilton’s shoes. As one competitor described him, Coleman became “the generalissimo of Federal editors.” The paper lives on today as the New York Post, the nation’s oldest continuously published daily newspaper.

Washington Irving (the author)

Another attorney who can be connected to the case was author Washington Irving. As a new lawyer, Irving apprenticed at Livingston’s law firm. It has been claimed that Burr’s daughter, Theodosia, who was also a writer, may have had affections for the young Washington Irving. Irving would later write for the New York Evening Post, but gained fame for his short stories, as the first American author to gain widespread acclaim in Europe.

Washington Irving would later famously label New York City “Gotham,” in his satirical magazine, The Whim-whams and Opinions of Launcelot Langstaff, Esq. & Others (also know as Salmagundi for short). Among other subjects, Irving’s satirical periodical Salmagundi also printed trial reports other political commentary. His 1809 work, A History of New York from the Beginning of the World to the End of the Dutch Dynasty, was written under his pseudonym Diedrich Knickerbocker. Of course, the name Knickerbocker was later adopted by the New York Knicks basketball team.

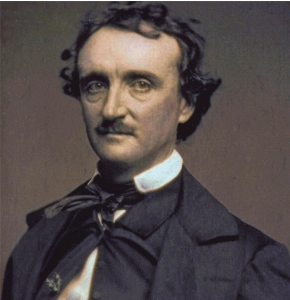

Edgar Allan Poe and the Dupin Mysteries

Scholar Richard Kopley, one of the foremost experts on Edgar Allan Poe, argues that the Elma Sands murder case serves as one of the two major influences on Edgar Allan Poe’s seminal short story, “The Mystery of Marie Rogêt.” Edgar Allan Poe and the Dupin Mysteries (Kopley, 2008). For those who aren’t yet Poe fans, this was the first ever detective story in which Poe invented the brand new genre. Other literary giants, including Arthur Conan Doyle, T.S. Elliot and Mark Twain were all fans of Poe’s detective, Monsieur Dupin.

Poet Philip Freneau and Lin-Manuel Miranda

It is perhaps no surprise that the celebrated murder trial found its way into popular culture. After the trial, newspaper editor and poet, Philip Freneau, dedicated a poem to Elma Sands. Philip Freneau, A Collection of Poems, on American Affairs and a Variety of Other Subjects (1815). Known as the “Poet of the American Revolution,” Freneau was a schoolmate of Madison’s. After the Constitutional Convention he became a harsh critic of Hamilton’s Federalist policies. The opening paragraph of Freneau’s poem about the Manhattan-well murder is copied below.

THE REWARD OF INNOCENCE (by Philip Freneau)

Could beauty, virtue, innocence, and love

Some spirits soften, or some bosoms move.

If native worth, with every charm combined,

Had power to melt the savage in the mind,

Thou, injured ELMA, had not fallen a prey

To fierce revenge, that seized thy life away;

Nor through the glooms of conscious night been led

To find a funeral for a nuptial bed,

When by the power of midnight fiends you fell,

Plunged in the abyss of Manhattan-well.

Two hundred years later, Lin-Manuel Miranda paid homage to the Weeks case in the Alexander Hamilton musical. It is easy to miss Aaron Burr’s quick reference to the Weeks trial in the frenetic song “Non-Stop.”

Lin-Manuel (Hamilton) sings to the “Gentlemen of the jury, I’m curious bear with me. Are you aware that we’re making hist’ry? This is the first murder trial of our brand-new nation.” An emphatic co-counsel, Aaron Burr (Leslie Odom) then declares, “Our client Levi Weeks is innocent. Call your first witness.” Fifty-four witnesses later, Levi Weeks was acquitted.

Additional reading:

Lispenard’s Meadow, Hidden Waters Blog

Estelle Fox Kleiger, The Trial of Levi Weeks or The Manhattan Well Mystery (1989)

Julius Goebel, Jr., The Law Practice of Alexander Hamilton (1964)

Gazette of the United States, April 4, 1800

Liva Baker, The Defense of Levi Weeks, ABA Journal (June, 1977)

Philip Freneau, A Collection of Poems, on American Affairs and a Variety of Other Subjects (1815)