The Justice of the Peace Act of 1361 and Justice of the Peace Manuals relevant to the Second Amendment

This post is the second part of a two-part post about the Statute of Northampton (2 Edw. 3, c. 3) and the Second Amendment. Part I discussed the Statute of Northampton in connection with the 2008 Supreme Court case of District of Columbia v. Heller and the pending case of New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen. Part I also discussed the Game Act of 1671 which restricted arms to the landed elite.

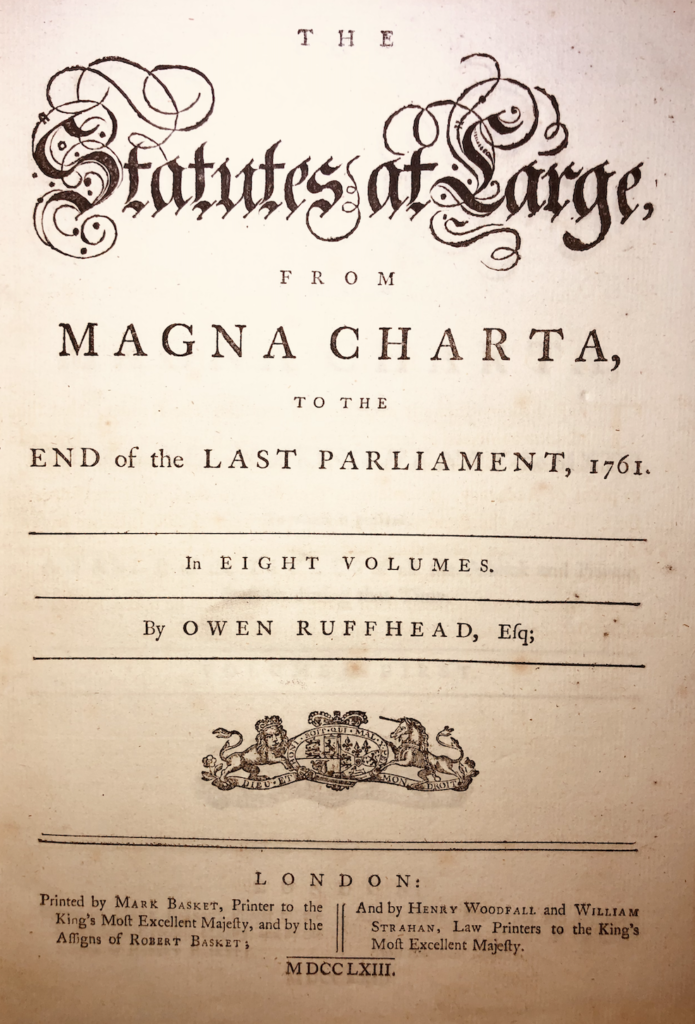

This post, Part II, continues with a discussion of the Justice of the Peace Act of 1361 (34 Edw. 3, c. 1), justice of the peace manuals cited in the Bruen case, and relevant sections of Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England. As many of these old authorities have been digitized and exist in the public domain, StatutesandStories.com is pleased to provide links and images of these antiquarian authorities and texts.

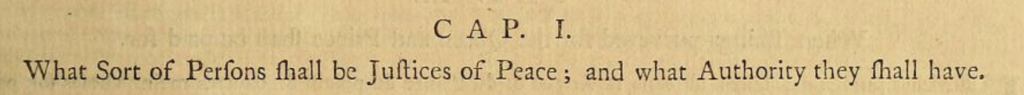

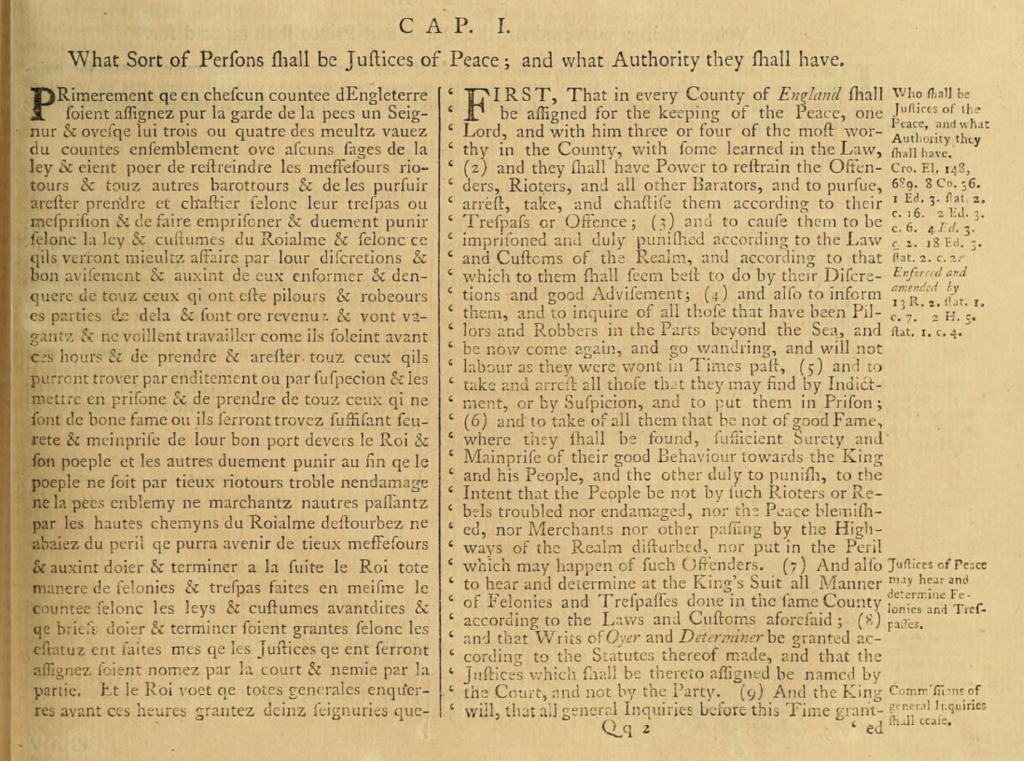

The Justice of the Peace Act of 1361

The Justice of the Peace Act of 1361 was adopted during the reign of King Edward III. The Act governed who was eligble to become a Justice of the Peace and defined their duties and powers. The Act provided for the selection in each county of a lord and three to four worthy people to be justices of the peace, responsible for dealing with “offenders, rioters, and all other barators.” While the role of the justices of the peace was not new, the 1361 Act helped perpetuate and empower the institution, particularly at a time when Parliament was concerned about soliders returning from war in France.

In Act called for the appointment “in every County of England,” for the “keeping of the Peace”:

one lord and with him three or four of the most worthy in the country, some learned in the law…..to pursue, arrest, take and chastise them according to their trespass and offence….and also to hear and determine at the King’s suit all manner of felonies and trespasses….according to the laws and customs aforesaid.”

Under the 1361 Act, the justices of the peace operated as modern day police who would pursue and arrest criminals. Unlike today’s police, justices of the peace were vested with the authority to imprison and “duly” punish offenders. They also had the authority to impose “reasonable and just” fines. Serving as a court, justices of the peace could try the majority of criminal and civil cases, except for the most serious felonies, which would be adjudicated by one of the King’s traveling courts.

Justices of the Peace Manuals cited in the Bruen case

Justices of the Peace Manuals were handbooks used by justices of the peace, who were not necessarily trained lawyers. Accordingly, justice of the peace manuals were an important resource, which were widely used by justices of the peace as they attempted to follow the correctly administer the law. Over time, as the law changed, justice of the peace manuals would be appropriately updated by printers.

In the case of New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen, English and American justice of the peace manuals are cited extensively. The Statute of Northampton and a particular justice of the peace manual were discussed during oral argument. Click here for a copy of the November 3 transcript.

The State of New York’s brief cites to James Ewing’s A Treatise on the Office & Duty of a Justice of the Peace at 546 (1805), The New-York Justice at 8(1815) by John Dunlap, and James Davis’ The Office and Authority of a Justice of the Peace at 13 (1774).

Older justice of the peace manuals were cited extensively in the amici briefs and are discussed below. According to the amicus brief filed by 17 preeminent professors of English and Amerian history and law, historical sources including justice of the peace manuals indicate that “it was widely understood, for centuries, that going armed in public was generally forbidden.” As examples, the professors cite to Joseph Keble’s popular justice of the peace manual from 1683 and William Lambarde’s 1606 manual.

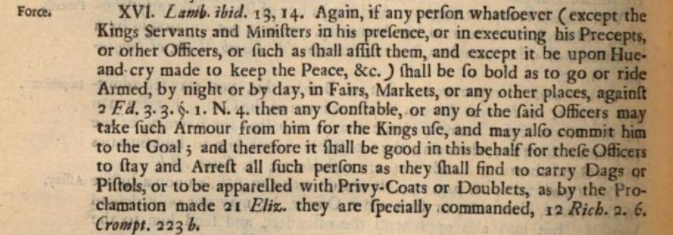

Keble’s justice of the peace manual, which is copied below along with its cover page, provides in relevant part that:

“[I]f any person … shall be so bold as to go or ride Armed, by night or by day, in Fairs, Markets, or any other places,” a justice of the peace may seize his arms and “commit him to the Goal.” Keble, An Assistance to the Justices of the Peace for the Easier Performance of Their Duty at 224 (1683)

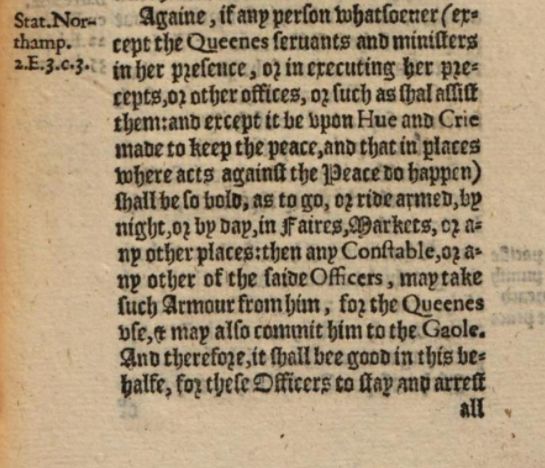

William Lambarde’s 1599 justice of the peace manual similarly explains:

“[I]f any person … shall be so bold, as to goe, or ride armed, by night, or by day, in Faires, Markets, or any other places: then any Constable … may take such Armour from him … and may also commit him to the Goale.” Lambarde, The Duties of Constables, Borsholders, Tythingmen, and Such Other Lowe and Lay Ministers of the Peace at __ (1599 ed.)

The English Bill of Rights was adopted in 1689 when Catholic King James II was deposed during the Glorious Revolution. While the Bill of Rights declared that “the subjects[,] which are protestants, may have arms for their defence suitable to their conditions,

and as allowed by law,” the amicus professors in support of New York argue that this provision “did not upend pre-existing restrictions on the right to carry arms,

nor did it preclude future restrictions.”

Thus, according to these esteemed professors, the English Bill of Rights “stated only

that the Protestants ‘may have Arms … as allowed by law,’ thereby continuing to condition the ability to carry arms on pre-existing and future restrictions, including the Statute of Northampton’s general prohibition on going armed in public.”

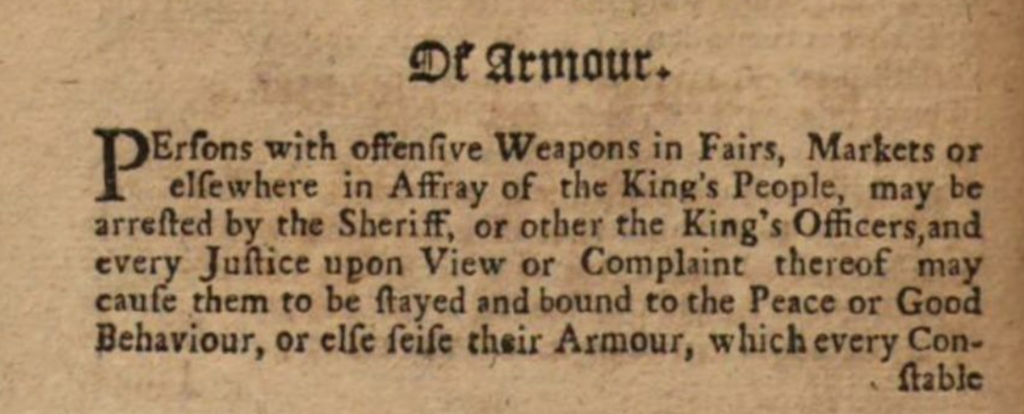

According to John Bond’s 1707 justice of the peace manual, “Persons with offensive Weapons in Fairs, Markets or elsewhere in Affray of the King’s People, may be arrested….” A Compleat Guide for Justices of the Peace at 42 (3d ed. 1707).

Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England

One of the most important treatises in Anglo-American history is Sir William Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England. Members of the founding generation who owned copies of Blackstone’s Commentaries included James Madison, Alexader Hamilton, Benjamin Franklin, and John Dickinson. While John Adams, Thomas Jefferson and John Marshall did not attend the Constitutional Convention, they also owned copies.

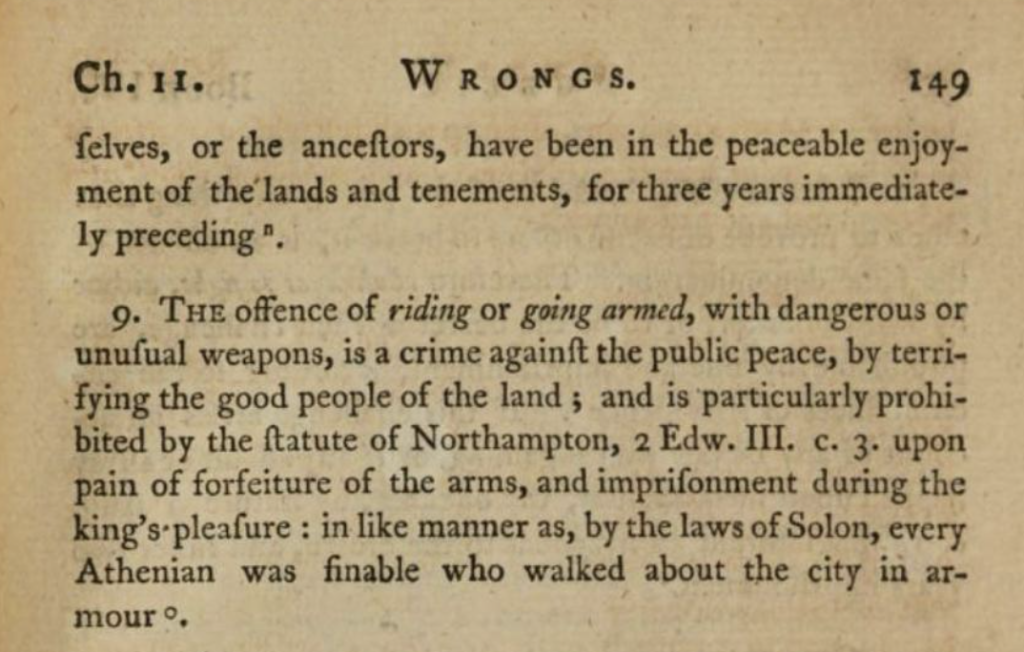

Blackstone explains that: “The offence of riding or going armed with dangerous or unusual weapons is a crime against the public peace, by terrifying the good people of the land, and is particularly prohibited by the Statute of Northampton.” 4 Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England at 148-149 (Oxford, England 1769).

According to Blackstone, English common law had a “special care and regard for the conservation of the peace,” because “peace is the very end and foundation of civil society.” 1 Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England at 338 (1765). The king was entrusted with preserving the “peace” and exercised a monopoly on violence “within all his dominions”. Thus, for the amicus professors, “the English common law viewed going armed in public places as an offense against the public peace and as a challenge to the monarchy’s power and authority.”