The Morris – Antill – Hamilton Connection (“Little Orphan Fanny” – Part 2)

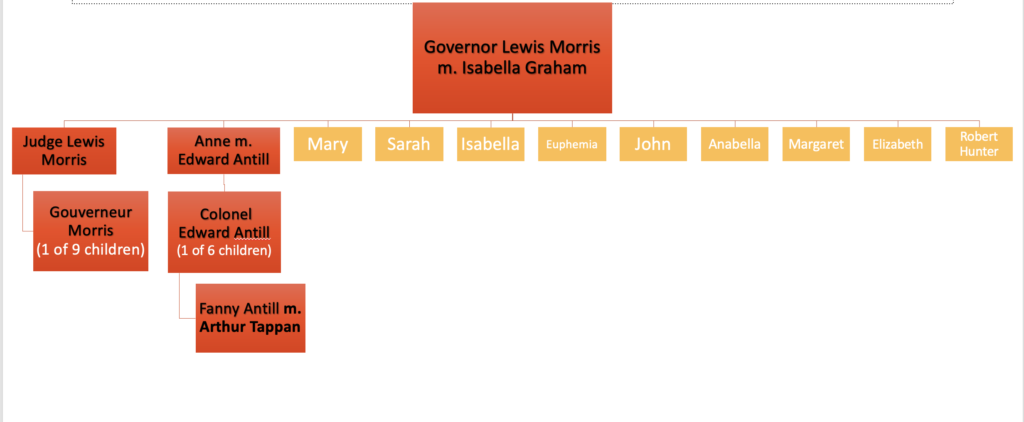

For decades historians have recognized the close friendship between Gouverneur Morris and Alexander Hamilton. Yet, the full extent of their relationship was not fully understood. Biographers have rightly applauded the generosity of Eliza and Alexander Hamilton when they brought two-year-old Fanny Antill into the Hamilton household in 1787. Newly uncovered evidence reveals that Fanny Antill and Gouverneur Morris were both descendants of New Jersey’s first colonial governor, Lewis Morris. In other words, Gouverneur Morris and Fanny’s father, Edward Antill, were both first cousins – and grandchildren – of Governor Lewis Morris.

This blog post: the Morris – Antill – Hamilton Connection (“Little Orphan Fanny” – Part II) is based on a wide-ranging investigation of genealogical records, wills, Revolutionary War pension rolls, family bibles, Gouverneur Morris’s papers, Alexander Hamilton’s papers, and Morris family papers, including the papers of New Jersey Governor Lewis Morris. Examination of these records produced a heretofore unknown, but in hindsight, not surprising discovery: Fanny Antill’s grandmother – Anne Morris Antill – was Gouverneur Morris’s godmother.

Famously, in 1787 the Hamiltons brought two-year-old Fanny Antill into the Hamilton household and raised her as their own daughter. Newly emerging evidence discussed in Part I demonstrates that there is more to the story than previously understood.

Part I surveys the evidence that Alexander and Eliza were already well acquainted with the Antill family when Alexander brought Fanny home to be raised by the Hamiltons. Historians have long recognized that Alexander Hamilton fought together with Fanny’s father, Edward Antill, at Yorktown. Newly uncovered church records, however, demonstrate that Eliza Hamilton became the godmother to Fanny and her sister Harriet in September of 1785, after the death of their mother, Charlotte Riverin Antill. As described in Part I, it is now clear that the Hamiltons had a pre-existing relationship with the Antill family which extended beyond the battlefield at Yorktown.

This blog post, Part II, explores the relationship between the Antill and Morris families. Genealogical records confirm that Colonel Edward Antill’s mother was Anne Morris, the aunt of founding father Gouverneur Morris. Otherwise stated, Colonel Antill and Gouverneur Morris were both grandsons of New Jersey Governor Lewis Morris. The revelation that Fanny Antill’s grandmother was Gouverneur Morris’s aunt suggests greater affinity between the Hamilton and Morris families than previously understood. Accordingly, when Alexander Hamilton and Gouverneur Morris were formulating the Constitution in 1787, Eliza Hamilton was raising little orphan Fanny, Gouverneur Morris’ cousin once removed. Moreover, as recently discovered, it turns out that Fanny’s grandmother – Anne Morris Antill – was Gouverneur Morris’s godmother.

For these reasons, Part II might also be described as the “Hamilton/Morris/Antill godparent connection.” The Hamiltons were godparents to Fanny Antill and her sister. Fanny’s grandmother, Anne Morris Antill, was the godmother of Gouverneur Morris, her nephew. While it’s not a perfect circle between the families, it becomes clear that godparents played an important role, prior to the existence of today’s governmental safety net programs.

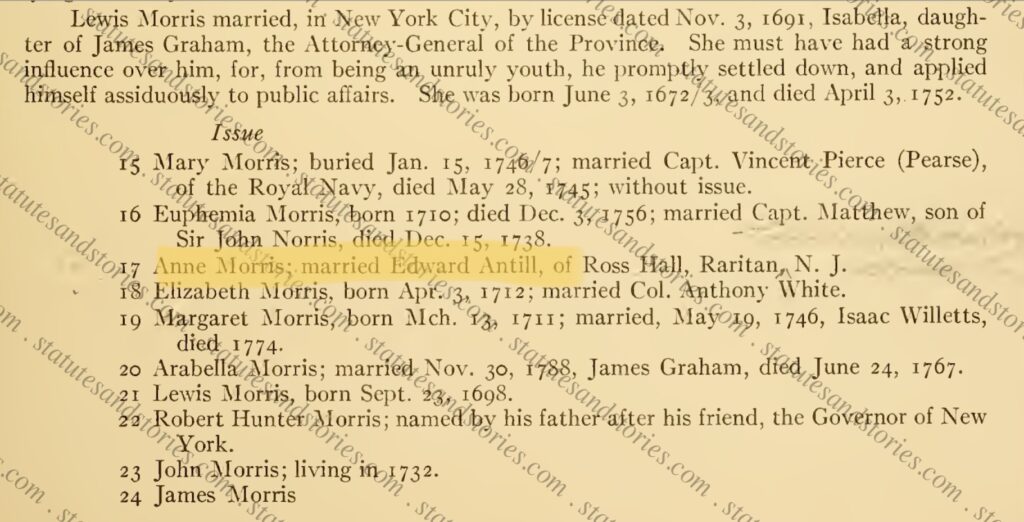

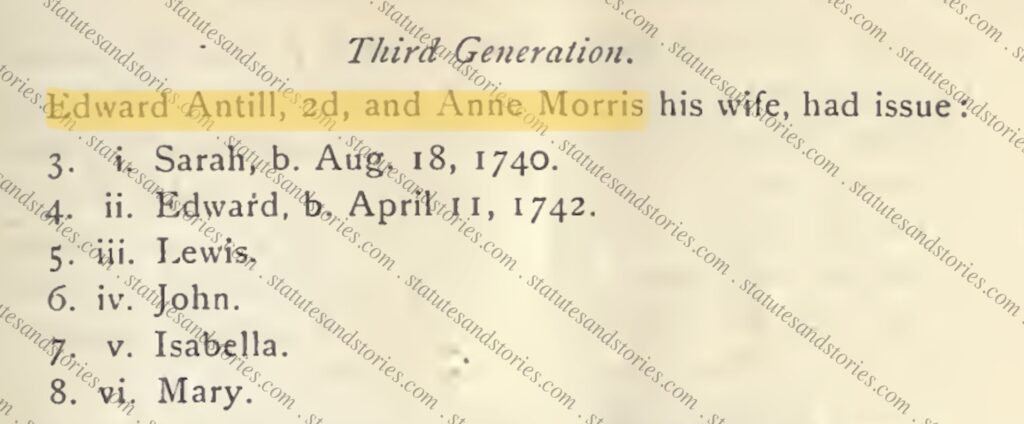

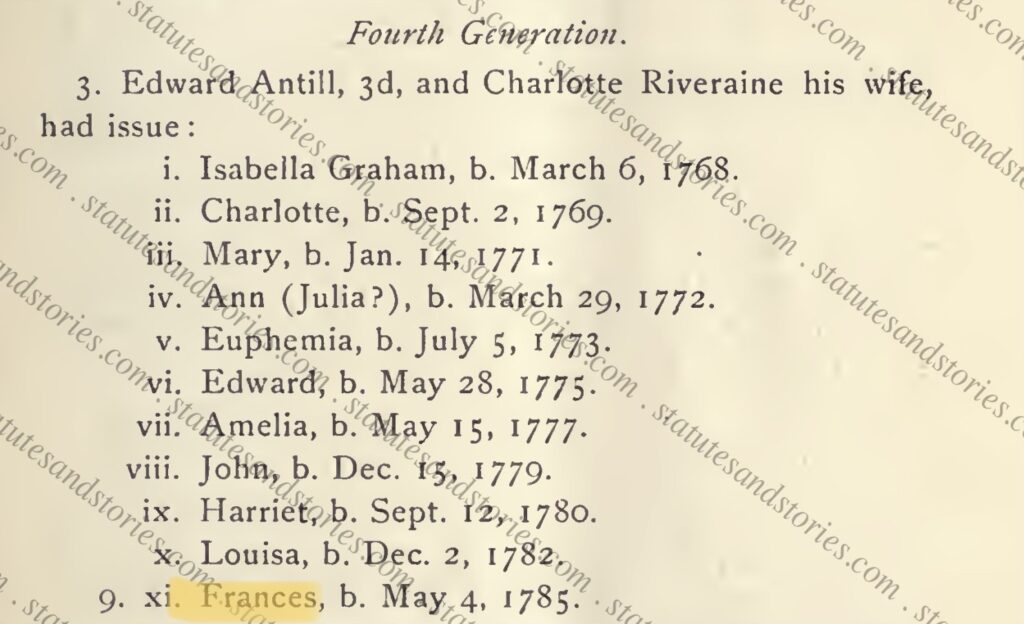

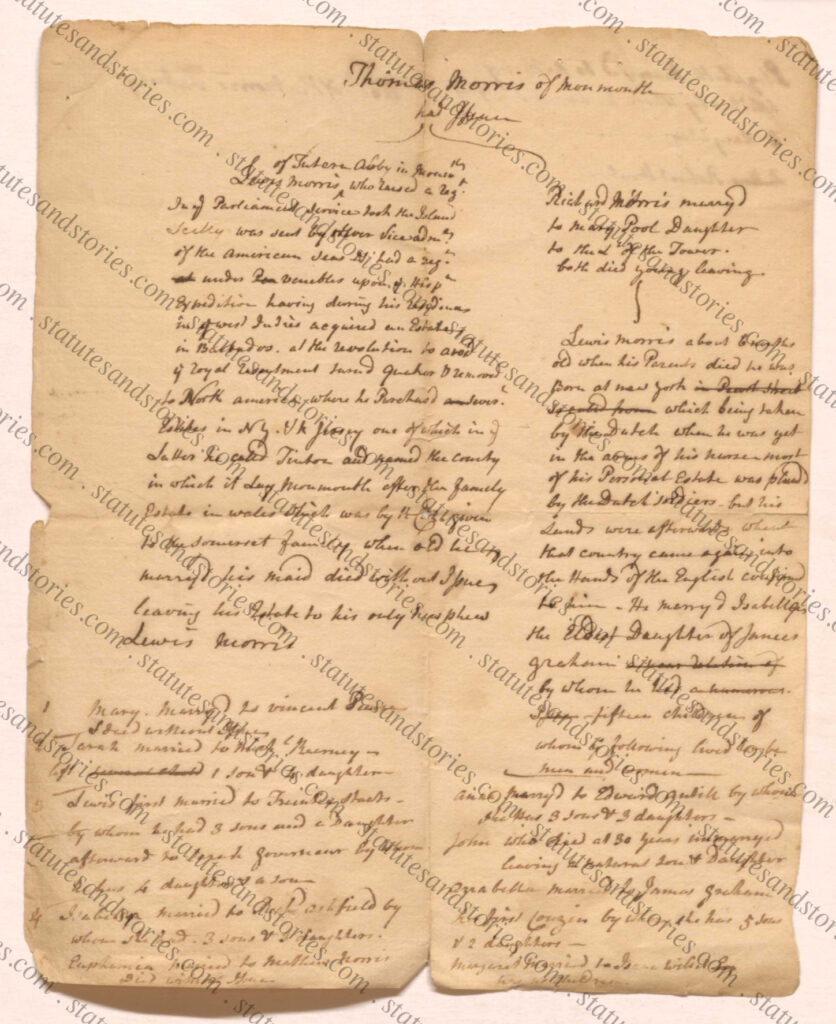

Copied below are Morris and Antill family genealogies which have been meticulously verified.

The genealogical record is clear. Fanny Antill, the Hamilton’s goddaughter, was the granddaughter of Gouverneur Morris’s aunt (and godmother), Anne Morris Antill.

Admittedly, researchers need to be cautious with secondary sources and genealogical records from the 18th and 19th centuries.[1] As described by Governor Lewis Morris’s biographer, “[i]ndustrious genealogists [are] sometimes too quick to credit their families with ancestors they did not actually have and virtues they did not really possess…”[2]

For this reason, multiple, independent, and redundant primary sources are cited below, along with secondary sources. All these records confirm the conclusion that Fanny (Frances Antill), born on May 4, 1785, was the granddaughter of Anne Antill Morris, Gouverneur Morris’s aunt and godmother.[3]

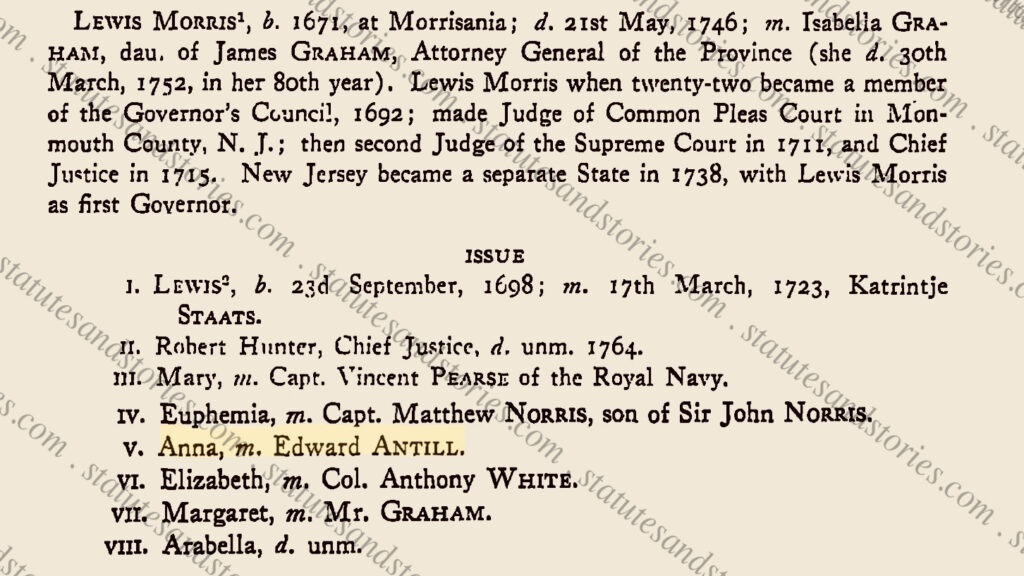

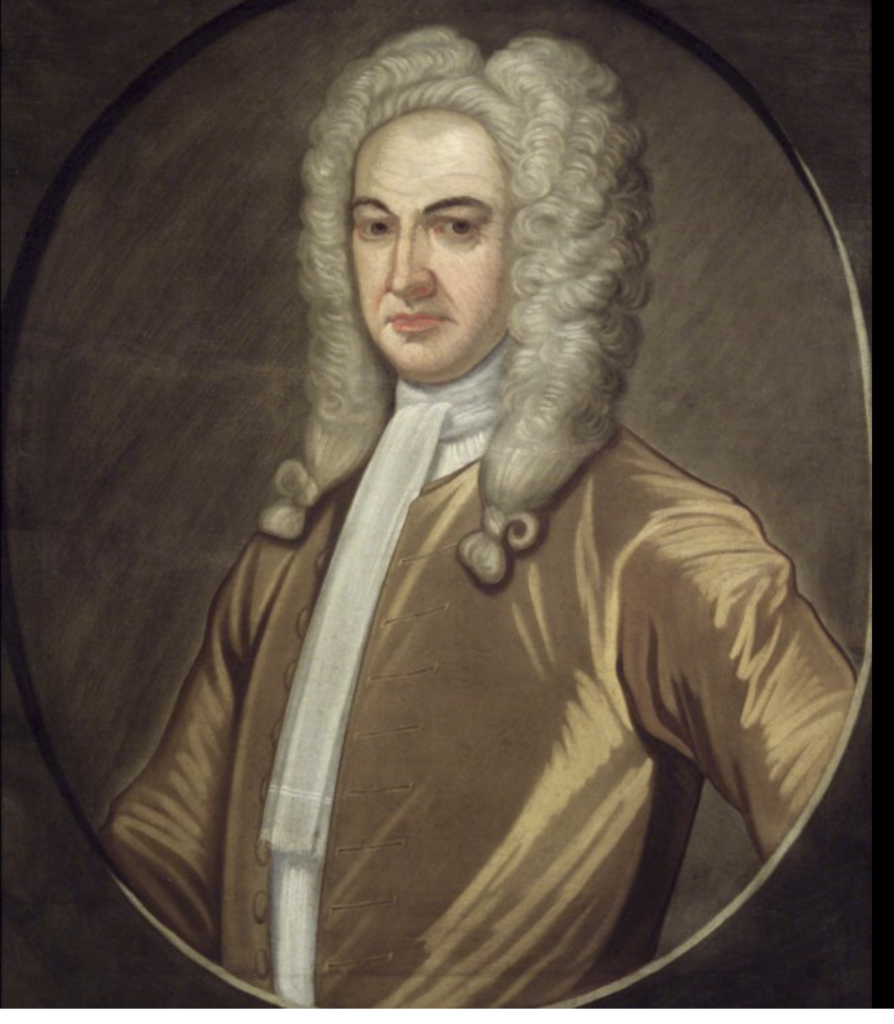

New Jersey Governor Lewis Morris – Fanny’s Great Grandfather

In 1738 King George II appointed Lewis Morris as New Jersey’s first royal governor, a position he held until his death in 1746.[4] Prior to his appointment, both New York and New Jersey were administered under a single royal governor. Lewis Morris had been serving as the Chief Justice on the New York Supreme Court of Judicature. After publishing a dissenting opinion in the case of Cosby v. Van Dam,[5] Morris was summarily removed by New York Governor Cosby. Morris traveled to England with his son to appeal the dismissal by Governor Cosby, which was declared illegal. Cosby’s actions gave rise to one of the most famous trials in American history, the seditious libel case of Crown v. Zenger.[6] As described by Gouverneur Morris biographer Richard Brookiser, “to get him out of New York” London offered Lewis Morris the governorship of New Jersey.[7] The rest is history.

Governor Lewis Morris is pictured above in a portrait from the Brooklyn Museum, painted circa 1726. In 1691 Lewis Moris married Isabella Graham, the daughter of New York Attorney General James Graham.[8] The couple had twelve children, including Lewis Morris (Gouverneur Morris’s father), Robert Hunter Morris (who became the Governor of Pennsylvania), and Anne Morris (who married Edward Antill), but not all the children survived to adulthood.

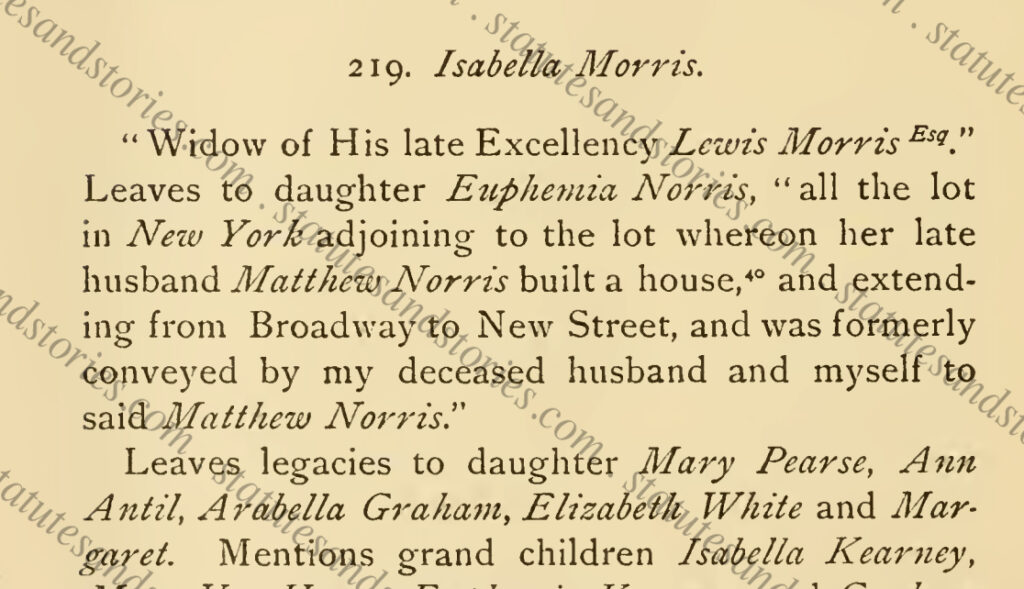

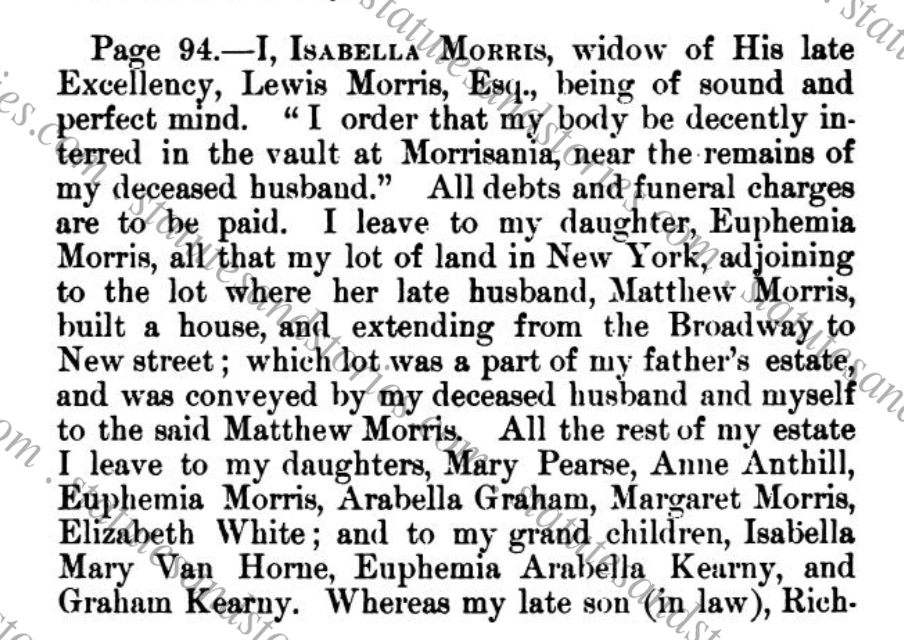

Isabella Graham Morris’s last will and testament is an important primary source which validates the secondary genealogical sources pictured above. Isabella’s will was executed in 1746 after Governor Lewis Morris died. The will was proved in 1752, the year of Isabella’s death. As pictured below, Isabella’s will confirms that Isabella Graham Morris was the “widow of His late Excellency, Lewis Morris.” Listed among Isabella’s daughters is “Anne Anthill,” who is a named beneficiary.

Isabella’s will directed that her body be buried in the family vault in Morrisania, near the remains of her deceased husband, Governor Lewis Morris. Property inherited from her father in New York was devised to her daughter Euphemia Morris. Her two sons, Lewis Morris[9] and Robert Hunter Morris were named as executors.[10]

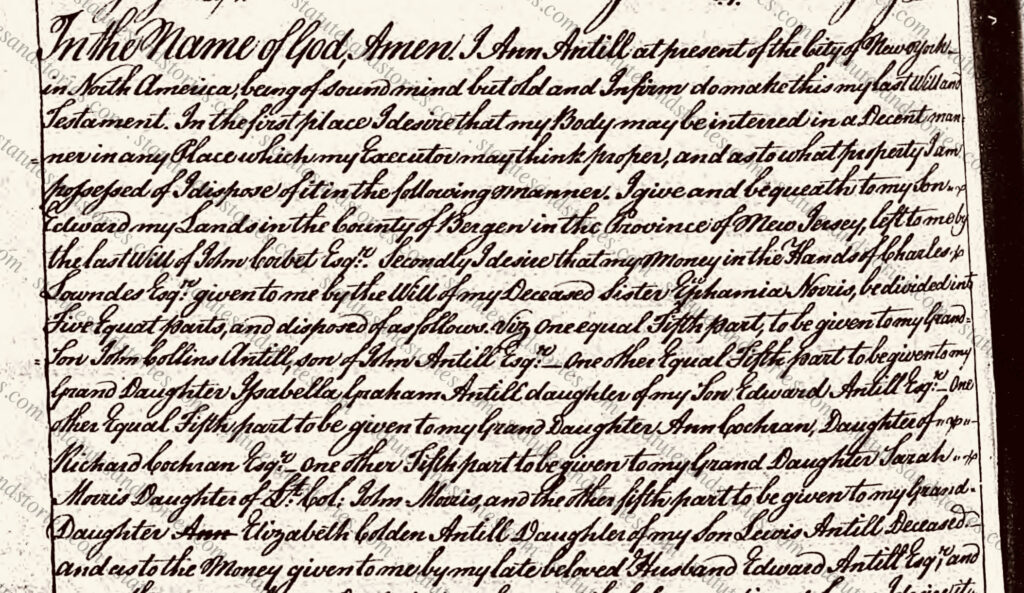

Thirty years later, during the Revolutionary War, Anne Morris Antill’s will was probated in 1781. It is striking how many of the same family names reappear across the generations. For example, Isabella bequeathed a legacy to her daughter, Euphemia Morris. Anne Morris Antill’s will likewise mentions Euphemia, her sister. Anne’s will lists her “son Edward Antill” as the beneficiary of family lands and mentions her “late beloved husband Edward Antill.” There can be no doubt that these wills align with the secondary genealogical sources cited above.

The papers of Governor Lewis Morris further confirm that his daughter, Anne Morris, married Edward Antill. For example, in a letter to the Lords of Trade dated March 3, 1743, Governor Morris describes how he prevailed on Edward Antill, “who is my son-in-law” to be a member of the board.[11] As early as October of 1738, Governor Morris appointed Edward Antill to the Assembly, representing Middlesex County. In a letter dated January 3, 1739, Governor Morris refers to Edward Antill as “my son Antill,” who Morris appointed to the Governor’s council.[12]

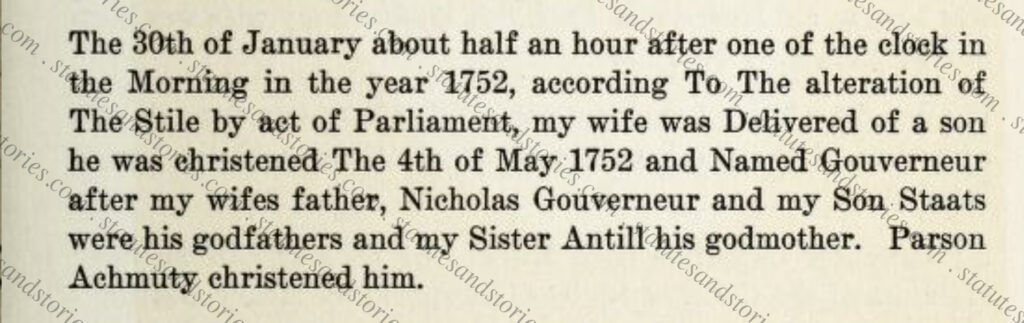

The most surprising primary source of all is Judge Lewis Morris’s family bible. Not only do the handwritten inscriptions confirm secondary genealogical sources, the inscriptions also contain the unexpected discovery that Anne Morris Antill was Gouverneur Morris’s godmother.[13]

Written in the first person by Judge Lewis Morris, the inscriptions record the birthdates and times of all of the Morris children along with other family information. According to Judge Morris, on January 30, 1752, my wife was delivered of a son, who was christened on May 4, 1752 and named Gouverneur after my wife’s father, Nicholas Gouverneur. Various Gouverneur Morris biographers have cited this fact to explain the origin of Gouverneur Morris’s first name. Nevertheless, the next line in the inscription has been entirely overlooked. The inscription identifies Gouverneur Morris’s godparents:

“[M]y wife’s father, Nicholas Gouverneur and my son Staats were his godfathers and my sister Antill his godmother.”

Thus, Judge Lewis Morris’s sister, Anne Morris Antill, was in fact Fanny Antill’s grandmother and Gouverneur Morris’s godmother. This obscure fact only becomes relevant when the pieces of evidence are compiled to demonstrate that Anne Morris Antill’s granddaughter was raised by the Hamilton family.

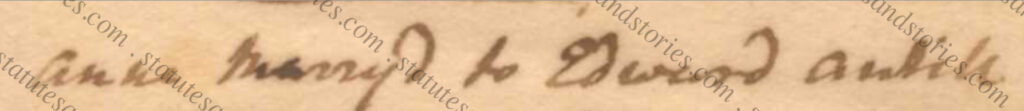

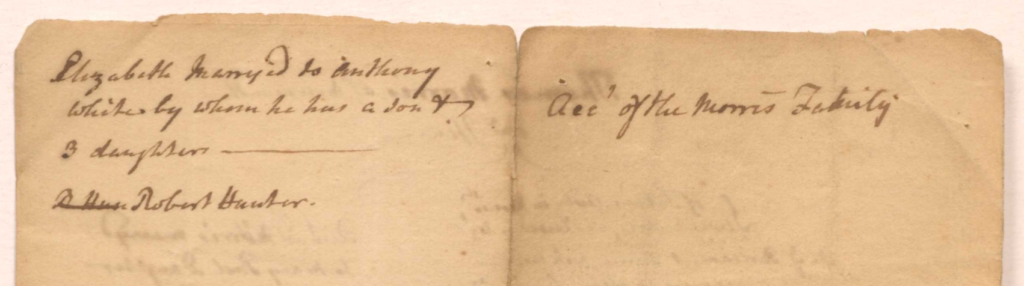

Pictured below is a handwritten “acc[ount] of the Morris family.” The document was located at the Library of Congress in the Papers of Lewis Morris. The notations, while difficult to read, perfectly align with the family history described above. According to the account, “Anne marry’d to Edward Antill…” Case closed.

Two additional names are mentioned on the back, Elizabeth and Robert Hunter. The title of the document, “acc’ of the Morris Family” is also visible at the top of the back side of the page.

The following abbreviated family tree was created using the bottom half of Lewis Morris’ “acc[ount] of the Morris family.” Assuming that the account was written by Judge Morris, he mentions that his father, Governor Lewis Morris, married Isabella, the oldest daughter of James Graham, by whom he had fifteen children of whom the following lived into adulthood:

Another useful primary source is the biography of Arthur Tappan, Fanny’s husband. Written years later by Arthur Tappan’s brother, Lewis Tappan, the biography provides further confirmation that Frances Antill was the daughter of Colonel Edward Antill. The biography also confirms that Fanny’s grandfather married Anne Antill Morris, the daughter of Governor Lewis Morris of New Jersey.[14] The Tappan biography also cites to Fanny’s obituary published in 1863 which likewise summarizes that Frances Antill Tappan’s grandfather, Edward Antill, married the daughter of Governor Morris of New Jersey. The obituary further describes that Edward Antill’s son, Colonel Edward Antill, “became the intimate associate of some of the most eminent of Washington’s subordinates” during the Revolutionary War.

Rounding out the list of sources which confirm the fact that Fanny Antill was the daughter of Colonel Edward Antill are publications and applications to the Sons of the American Revolution (SAR), Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR), and records of the Society of the Cincinnati.[15] These and other sources indicate that Fanny married Arthur Tappan. Fanny’s older sister, Harriet, married Colonel Garrit G. Lansing, the brother of Constitutional Convention delegate John Lansing, Jr.[16]

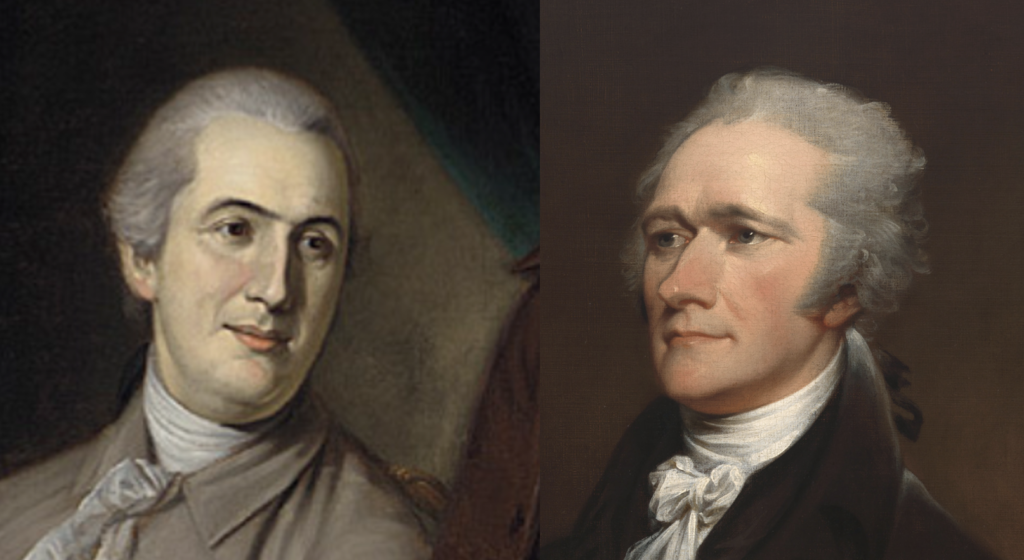

“Friends to the End” – Alexander Hamilton and Gouverneur Morris

Prior research described on StatutesandStories.com has identified previously unknown connections between Alexander Hamilton and Gouverneur Morris. Among other things, Hamilton was receiving mail “at Gouverneur Morris” in Philadelphia in 1787. Hamilton and Gouverneur Morris shared substantially similar objectives going into the Constitutional Convention and worked closely together on the Committee on Style in September of 1787. As discussed above, we now know that Gouverneur Morris and Alexander Hamilton shared deep family connections through Fanny’s introduction into the Hamilton household in 1787, after the Hamiltons became godparents to Fanny and her sister in 1785.

Richard Brookhiser, a biographer of both Alexander Hamilton and Gouverneur Morris, indicates that “professionally and politically they were soul-mates.”[17] Hamilton biographer Forrest McDonald notes that after meeting at Valley Forge Hamilton and Morris would become “intimate social and political” friends for the rest of Hamilton’s life.[18] Others, including Eliza Hamilton, have opined that Morris was “Hamilton’s best friend.”[19] Peter Charles Hoffer, describes Gouverneur Morris as “Hamilton’s friend to the end.”[20]

When they first met in 1777, Alexander Hamilton was an aide-de-camp for General Washington while Gouverneur Morris served on the New York Committee of Correspondence. After helping draft New York’s state constitution Morris sent a copy to Hamilton to review. Hamilton’s comments would prove to be very similar to his view on the U.S. Constitution drafted by Morris and Hamilton a decade later in 1787.[21]

In a letter to their mutual friend, Rufus King, Hamilton said of Morris that “Men like him do not super-abound.”[22] In turn, Morris praised Hamilton’s “brilliant” service during the War, “heroic spirit,” “splendid talents,” and “incorruptible integrity.”

Well-known examples of the deep friendship and longstanding working relationship between Hamilton and Morris include the following:

- Although they came from different backgrounds, Hamilton and Morris traveled in the same circles[23]

- Hamilton and Morris both went to King’s College (but not at the same time)[24]

- Hamilton and Morris were both proud, cosmopolitan New Yorkers who favored aristocratic checks on democratic excesses[25]

- During and after the Revolutionary War they were both strong supporters of George Washington. As ardent nationalists they recognized the need for an energetic federal government that could address national issues[26]

- Both worked to restore national finances with Morris as the assistant to the Superintendent of Finance (Robert Morris) and Hamilton becoming the first Treasury Secretary, upon Robert Morris’s recommendation to George Washington[27]

- Hamilton and Morris boarded together at the Constitutional Convention at Miss Dally’s boarding house[28]

- After the Convention, Hamilton asked Morris to help write Federalist essays. Both were accomplished writers and pamphleteers, with Morris serving as the unofficial penman for Congress opposing the British Carlisle Commission. While Hamilton’s essays are well known, Morris’s Observations on the American Revolution and his An American essays align with Hamilton’s writings. [29]

- Both were outspoken opponents of slavery[30]

- Morris was one of only a handful of friends at Hamilton’s deathbed[31]

- Morris’s nephew, David Bayard Ogden, was also present with the Hamilton family when Hamilton passed[32]

- Morris provided the effusive eulogy at Hamilton’s funeral[33]

- After Hamilton’s death, Morris secretly organized a subscription to financially support the Hamilton family with a trust fund. Morris also took Hamilton’s place on the Columbia College board of trustees.[34]

The following recently discovered connections between Hamilton and Morris are discussed at length in prior posts on StatutesandStories.com setting forth the underlying research:

- Morris recommended Hamilton to represent Morris’s loyalist mother, Sarah Morris, after the Revolutionary War. Morris correctly anticipated that his mother would be sued by his half-brother, Richard Morris. [35]

- As discovered in 2022, an orphaned fragmentary file in the Hamilton Papers definitively proves that Hamilton worked with Morris on the Morrisania loyalist claim on behalf of Morris’s mother[36]

- Documentary evidence similarly suggests that Hamilton assisted Morris in the complex Morrisania family probate litigation and the eventual purchase of the Morrisania family estate in the Bronx by Gouverneur Morris[37]

- Hamilton’s father-in-law, Philip Schuyler, was brought in as an arbitrator in the Morrisania family litigation[38]

- Hamilton received mail “at Gouverneur Morris”, prior to arriving at the Constitutional Convention.[39]

While Hamilton may not have known that Anne Morris Antill was Gouverneur Morris’s godmother, it is hard to believe that Hamilton and Morris didn’t realize that Fanny was a descendant of New Jersey Governor Lewis Morris. It is even harder to believe that Morris wouldn’t have appreciated the generosity of the Hamilton family in raising little orphan Fanny. Perhaps this is one of the reasons why Morris returned the favor by helping the Hamilton family, after the tragic duel in 1804.

Part III: the Dally/Morris/Antill/Hamilton/Ogden/Lansing Connection (pending) will discuss the long-standing social connections between the Dally and Morris/Antill/Hamilton/Ogden/Lansing families. Mary Dally operated an important boarding house in Philadelphia where Gouverneur Morris and other founders resided in the late 18th Century. Newly emerging evidence suggests that in 1739 the Dally family was “bound to” Lewis Morris, the Governor of New Jersey. While it is unclear whether Miss Dally was aware of the relationship between her father and Gouverneur Morris’s grandfather, it is no surprise that Gouverneur Morris boarded with Miss Dally in the early 1780s and continued living with Miss Dally during the Constitutional Convention. Part III will also attempt to connect the dots between Colonel Edward Antill who fought with Hamilton at Yorktown, along with Gerrit Lansing, who would later marry Fanny’s sister.

Given the deep-seated political differences between Alexander Hamilton and John Lansing in 1787, it is poetic that a Morris, raised by a Hamilton, could marry a Lansing.

Footnotes

[1] For example, one of the sources cited below incorrectly describes Gouverneur Morris as a signer of the Declaration of Independence. Historical and Genealogical Miscellany: Early Settlers of New Jersey and their Descendants, John E. Stillwell, M.D., volume IV:44 (New York 1916). For this reason, all claims discussed below have been carefully verified, since well-intentioned 19th century genealogists are not necessarily trained historians.

[2] Eugene R. Sheridan, Lewis Morris: A Study in Early American Politics, Syracuse University Press, 1 (1981). Professor John P. Kaminski similarly provided the friendly warning that Yogi Berra’s apocryphal advice applies to genealogy. When genealogists come to an uncertain fork in the road they are inclined to take it.

[3] Certain genealogical records refer to Anne Antill Morris as “Anna” or “Ann.” This is another example of why it is critical to independently verify genealogical claims with primary sources. Whether known as Anne, Anna or Ann, these sources agree that she was the daughter of Governor Lewis Morris and married Edward Antill, the oldest son of Edward Antill, on June 10, 1739. Compare George Norbury MacKenzie, LL.B, Colonial Families of the United States of America, Vol. VI, 376, Baltimore: The Seaforth Press, 1917 (indicating that “Anna, m. Edward Antill”) with John E. Stillwell, M.D., Historical and Genealogical Miscellany: Early Settlers of New Jersey and their Descendants, Vol. IV, 33 & 35 New York: 1916 (indicating that “Ann Morris” daughter of Lewis Morris married Edward Antill, 2nd on June 10, 1739) with William Nelson, Edward Antill and His Descendants, 15 & 19, Paterson: The Press Printing & Publishing Company, 1899 (indicating that “Anne Morris, daughter of Governor Morris” married Edward Antill, 2d on June 10, 1739). In turn, Anne’s son, Lt. Colonel Edward Antill, 3rd would marry Charlotte Riveraine, Fanny’s parents.

[4] Lewis Morris, Chief Justice of the New York Supreme Court of Judicature, Historical Society of the New York Courts: https://history.nycourts.gov/figure/lewis-morris/

[5] Cosby v. Van Dam, 1733, Historical Society of the New York Courts: https://history.nycourts.gov/case/cosby-v-van-dam/

[6] Morris’s dissenting opinion in the case of Cosby v. Van Dam precipitated the landmark libel case of Crown v. Zenger. New York’s first independent paper, the New-York Weekly Journal, printed satirical articles lampooning Governor Cosby’s retaliation against Justice Morris. John Peter Zenger, the New-York Weekly Journal’s printer, was criminally charged with seditious libel. Vindicating freedom of the press, a jury refused to convict in an early example of jury nullification. Years later Gouverneur Morris described the Zenger case as “the germ of American freedom, the morning star of that liberty which subsequently revolutionized America.” John R. Vile, ed., Great American Lawyers: An Encyclopedia, Bloomsbury, 2001, 331.

[7] Richard Brookhiser, Gentleman Revolutionary: Gouverneur Morris, the Rake Who Wrote the Constitution, New York: Free Press, 2003, 4; Eugene R. Sheridan, Lewis Morris: A Study in Early American Politics, Syracuse University Press, 179-180 (1981).

[8] William Howard Adams, Gouverneur Morris: An Independent Life, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003, 9; W. W. Spooner, American Historical Magazine, “The Morris Family of Morrisania,” 1:44 (1906).

[9] Lewis Morris, II (1698-1762), the son, is frequently referred to as “Judge” or “Colonel” Lewis Morris to distinguish him from his father, Governor Lewis Morris (1671 – 1746), who was also a judge. Accordingly, Gouverneur Morris, the “Penman of the Constitution” was the son of Judge Lewis Morris and the grandson of Governor Lewis Morris.

[10] Isabella’s will is abstracted in the book, Early Wills of Westchester County, New York, from 1664 to 1784, William S. Pelletreau, ed., New York: Francis P. Harper, 1898, 120.

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=yale.39002024307952&seq=13

The will is reprinted at length in Collections of the New-York Historical Society for the year 1895, Abstracts of Wills on file in the Surrogate’s Office, City of New York, Vol. IV, 1744-1754, 382.

https://archive.org/details/abstractswillso02kellgoog/page/381/mode/1up?view=theater

[11] New Jersey Historical Society, The Papers of Governor Lewis Morris, 182 (1852).

https://archive.org/details/papersoflewismor0000newj/page/n5/mode/2up?view=theater&q=antill

[12] The Papers of Governor Lewis Morris, p. 79 & 219. (1852).

[13] According to published records, the family bible was the property of Alexander Rutherford of Old Lyme, Conn, a great grandson of Judge Lewis Morris. Genealogical Records: Manuscript Entries of Births, Deaths and Marriages, Taken from Family Bibles 1581-1917, Jeannie F-J. Robinson & Henrietta C. Bartlett, eds., The Colonial Dames of the State of New York, 1917, 151.

https://archive.org/details/genealogicalreco00robi/page/151/mode/1up?view=theater

[14] Lewis Tappan, The Life of Arthur Tappan, p. 53 (1870) (indicating that Colonel Edward Antill’s mother was the daughter of Governor Morris from New Jersey). Lewis Tappan was the brother of Arthur Tappan, Fanny’s husband.

[15] SAR Application of Thornoton MacNess Niven, a lineal descendent of Colonel Edward Antill, dated 9 September 1920 (indicating that Edward Antill, son of Ann Morris, was the grandson of Governor Lewis Morris); John Schuyler, Institution of the Society of the Cincinnati of the New York State Society, 153 (1886).

[16] Lewis Tappan, The Life of Arthur Tappan, p. 54 (1870). Cite…

[17] https://nypost.com/2015/07/10/july-11-1804-how-alexander-hamiltons-friends-grieved/

[18] Forrest McDonald, Alexander Hamilton: A Biography, 18 (1982).

[19] David B. Ogden, Four Letters on the Death of Alexander Hamilton, 12 (1804). William Treanor, The Case of the Dishonest Scrivener: Gouverneur Morris and the Creation of the Federalist Constitution, 120 Mich Law Rev 28 (Oct. 2021).

[20] Peter Hoffer, For Ourselves and Our Posterity: The Preamble to the Federal Constitution in American History, 11 (2013).

[21] James Kirschke suggests that Hamilton may have met Gouverneur Morris for the first time at John Jay’s wedding to Sally Livingston in April of 1774. The lavish affair was held at William Livingston’s New Jersey estate known as “Liberty Hall.” James J. Kirschke, Gouverneur Morris: Author, Statesman, and Man of the World, 24, New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2005. Alexander Hamilton’s letter to Gouverneur Morris is dated 19 May 1777.

https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-01-02-0162

[22] Alexander Hamilton to Rufus King dated 2 October 1798. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-22-02-0105

[23] According to Richard Treanor:

“There was a natural bond between the two, outgoing, witty New Yorkers, both lawyers, both educated at Columbia, with similar politics and a common interest in finance (although, as will be discussed, very different personal backgrounds). The two had first worked together during the Revolutionary War when Hamilton was aide de camp to Washington and Morris a member of the Continental Congress inspecting the military. Hamilton revered the slightly older Morris for his intelligence and presence, and the two established a strong friendship. They worked closely together when Hamilton was in Congress and Morris the Assistant Superintendent of Finance.”

https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/213035906.pdf

[24] Id.

[25] Id.

[26] While they came from strikingly different backgrounds, both Hamilton and Morris shared a similar “continental” perspective and disdain for narrow, parochial prerogatives which undermined abiding national interests. According to Ron Chernow, “By dint of his youth, foreign birth, and cosmopolitan outlook, [Hamilton] was spared prewar entanglements in provincial state politics, making him a natural spokesman for a new American nationalism.” Ron Chernow, Alexander Hamilton, 157 (2004).

[27] Charles Rappleye, Robert Morris: Financier of the American Revolution, New York: Simon & Schusterp, 2010, 454.

[28] https://www.statutesandstories.com/blog_html/committee-on-style-venue-hypothesis-miss-dally-part-iv/

[29] Richard Brookhiser, Gentleman Revolutionary: Gouverneur Morris, the Rake Who Wrote the Constitution, New York: Free Press, 2003, 93.

[30] 2 Farrand at 221- 223. Akhil Reed Amar, America’s Constitution: A Biography (Random House, 2005) at 89.

[31] David B. Ogden, Four Letters on the Death of Alexander Hamilton, 1804; Found in the Papers of William Meredith of Philadelphia. Portland, Me.: Anthoensen Press, 1980.

[32] David B. Ogden, Four Letters on the Death of Alexander Hamilton, 1804; Found in the Papers of William Meredith of Philadelphia. David B Ogden was described as a “friend of Hamilton” by Ron Chernow. It is also clear that the two attorneys worked together and were colleagues. David Ogden, Alexander Hamilton and John B. Church were waiting for Morris when he returned from France in December of 1798. James J. Kirschke, Gouverneur Morris: Author, Statesman, and Man of the World, 249, New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2005.

[33] https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-26-02-0001-0271

During the eulogy Morris praised Hamilton who never sacrificed his own judgment. Morris asked fellow citizens to consider the following test to examine those who solicit your favour: What would Hamilton do?

[34] James J. Kirschke, Gouverneur Morris: Author, Statesman, and Man of the World, 259, New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2005. Kirschke cites Morris’s diary entry on July 14, 1804 involving the creation of the Hamilton family trust fund. The trust fund remained such a closely guarded secret that the Hamilton children did not learn of its existence for a decade. Chernow, Alexander Hamilton, at 725. For Morris’s work on the Columbia board of trustees, Kirschke points to Morris’s letter to his niece, Gertrude Meredith, dated 21 May 1810.

[36] https://www.statutesandstories.com/blog_html/mystery-solved-in-the-hamilton-papers-at-the-library-of-congress/

[37] https://www.statutesandstories.com/blog_html/unlikely-arbitrators-philip-schuyler-and-governor-clinton-more-surprises-in-morrisania-case/

[38] https://www.statutesandstories.com/blog_html/unlikely-arbitrators-philip-schuyler-and-governor-clinton-more-surprises-in-morrisania-case/

[39] https://www.statutesandstories.com/blog_html/mystery-solved-in-the-hamilton-papers-at-the-library-of-congress/