Schuyler & Clinton: Unlikely arbitrators in the Morrisania case

Mystery Solved at the Library of Congress – Morrisania Part II

Historic investigations can take surprising turns. A solution for one inquiry can raise entirely new and unexpected questions. This is the beauty of archival research. As recognized by Mark Twain, the truth can be stranger than fiction.

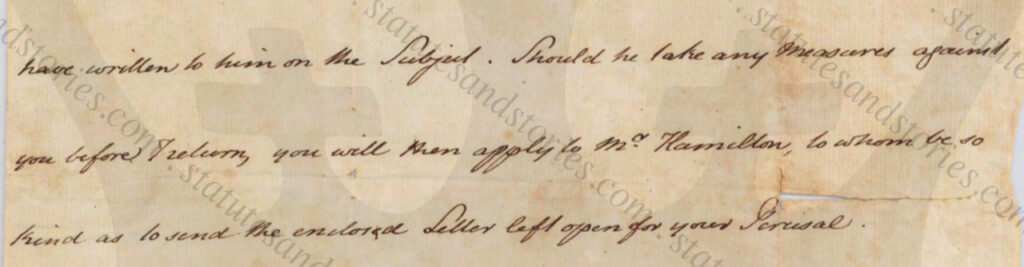

A recent discovery involving a fragmentary file in the Hamilton Papers at the Library of Congress has revealed an untold story that unites political rivals in totally unexpected ways. The emerging details also reinforce the professional collaboration and deep friendship between Gouverneur Morris and Alexander Hamilton in the years preceding the Constitutional Convention. These colleagues would work closely together on the Convention’s final committee, the Committee on Style and Arrangement, where the penultimate draft of the Constitution was drafted. Perhaps most surprising, however, is the revelation that political adversaries Philip Schuyler and George Clinton were recruited as arbitrators to help settle the complex Morrisania case.

As described below, Alexander Hamilton’s “Morrisania case” brings together his father-in-law, Philip Schuyler, New York Governor George Clinton, John Jay, Aaron Burr, Dowager Sarah Morris (Gouverneur’s mother), Staats Long Morris (a British General and member of Parliament), Isaac Wilkins (a notorious loyalist allied with Samuel Seabury), Richard Morris (the Chief Justice of the New York Supreme Court), Lewis Morris (a signer of the Declaration of Independence) and Gouverneur Morris (the indispensable draftsman of the Constitution).

This blog post – Morrisania Part II – is the second of a multi-part series telling the story of how an orphaned file in the Hamilton Papers at the Library of Congress connects the Papers of Gouverneur Morris at Columbia University and the Loyalist Collection at the University of New Brunswick.

Part I began by connecting the dots between an overlooked and fragmentary page in the Hamilton Papers at the Library of Congress and the “Morrisania Claim on the British Government,” which was submitted to the British Board of Claims on 18 October 1783. In hindsight, it is not surprising that Alexander Hamilton would have represented loyalists in the Morris family. Yet, the involvement of Schuyler, Clinton, and Burr in the case is a previously unknown and unexpected discovery. The prospect that Alexander Hamilton was working closely with Gouverneur Morris in the months preceding the Constitutional Convention is even more tantalizing.

Part II describes the complex maneuvering that enabled Gouverneur Morris, the youngest of four brothers, to purchase the Morrisania estate in 1787. It is now clear that the arbitration award by Schuyler and Clinton helped settle protracted probate litigation within the Morris family, involving Revolutionary War claims for damages pending in London.

After providing background for the Morris family and their legal disputes, Part II argues that it was no coincidence that Schuyler and Clinton were chosen to arbitrate the Morrisania probate litigation. This post theorizes that Hamilton purposely selected Governor Clinton and Senator Philip Schuyler in an effort to generate goodwill between the political rivals in the weeks leading up to the Constitutional Convention.

Alternatively, the selection of Governor Clinton and Philip Schuyler as arbitrators may have been intended to send a message to London. Gouverneur Morris’ half-brother, Staats Long Morris, was a member of Parliament. Employing Clinton and Schuyler as arbitrators may have been an effort to signal to London that New York’s political leadership would respect the results of the Morrisania settlement, in a case which with potential geopolitical implications.

Part I demonstrated that Hamilton assisted Sarah Morris with her loyalist claim in 1783. After this discovery, it remained unclear whether Hamilton continued to represent Sarah in subsequent probate litigation between members of the Morris family. Part II answers this question.

No Morris or Hamilton scholar has previously connected Alexander Hamilton to the Morrisania probate litigation. Yet, Part II argues that it is now clear that Hamilton and Morris were coordinating together for years, on multiple matters.

This blog post presents new evidence that Gouverneur Morris arranged for Alexander Hamilton to represent Sarah Morris. In 1784, Gouverneur anticipated that his mother would be sued by Gouverneur’s half-brother, Richard Morris. Despite Gouverneur’s efforts at conciliation, Richard brought suit in 1785.

This post will continue in Part III (pending) with a discussion of as yet unanswered questions for further investigation. For example, did Hamilton and Gouverneur Morris decide to recruit Schuyler and Clinton as a means of building goodwill between the political rivals in anticipation of the Constitutional Convention? Or was it necessary to recruit high-level political elites in a case involving a member of Parliament?

Perhaps Hamilton believed that the unlikely pairing of Clinton and Schuyler would help to convince London to pay maximum settlement value for the Morris family’s pending claim with the British Board of Claims? Who was Aaron Burr representing in the case? What was the Chief Justice, Richard Morris, hoping to gain by suing his step-mother?

The mounting evidence of coordination between Hamilton and Gouverneur Morris in the months preceding the Constitutional Convention is of keen interest to Constitutional scholars. For example, coordination between Hamilton and Morris provides evidentiary support for the Hamilton Authorship Thesis, which involves Hamilton and Morris’ work together on the Committee on Style in September of 1787. Click here for a discussion of the recent discovery that Hamilton arrived in Philadelphia earlier than previously understood.

Background about the Morris Family and the Will of Gouverneur Morris’ father

To make sense of the complex Morrisania claim and probate litigation it is useful to begin with an overview of the Morris family and their Morrisania estate. Ultimately, Gouverneur Morris was able to purchase Morrisania in 1787, even though he was the youngest of the four Morris brothers.

Gouverneur Morris’ family had deep roots in America. Many of the founding fathers were politically active prior to the Revolutionary War. Others came from influential families. As described by biographer Richard Brookhiser, “Morris was one of the few to spring from the governing elite.”

The Morris family arrived in America in the 1670s. Lewis and Richard Morris fought for Cromwell during the English Civil War. After the Restoration the two brothers eventually settled in New York where the family prospered. They acquired 1,900 acres north of New York City. The Morrisania estate extended from the Harlem River to the Long Island Sound. Lewis also purchased 3,500 acres in New Jersey.

Lewis Morris never had any children. Richard Morris named his son Lewis. The younger Lewis inherited the Morrisania estate after his uncle’s death. In 1697 Lewis became a manor lord, a quasi-feudal status shared by only a dozen other prominent New York families. As manor lord, Lewis held office in the New York colonial Assembly. He served as the Chief Justice of the New York Supreme Court at the time of the famous Zenger case and eventually became the Governor of New Jersey.

Over the next several generations, the Morris family continued to serve in the New York Assembly and judiciary. One member of the family, Robert Hunter Morris, became the Deputy Governor of Pennsylvania (1754-1756) and the Chief Justice of New Jersey. Twenty years later, the fourth Lewis Morris, Gouverneur Morris’ half-brother, would sign the Declaration of Independence.

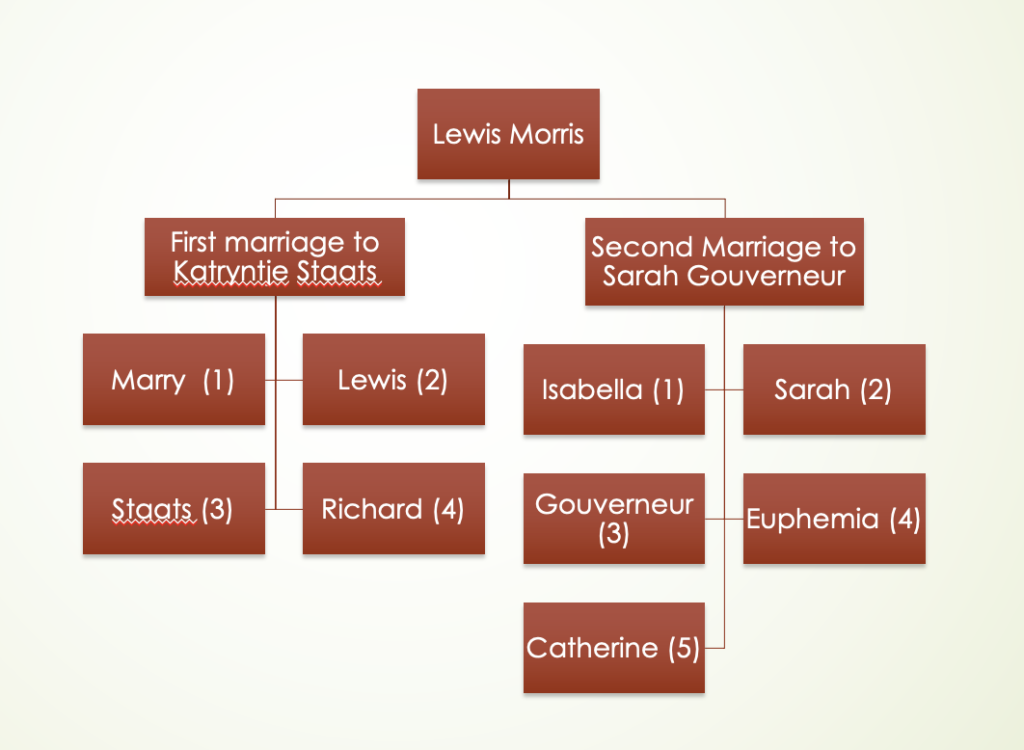

The penman of the U.S. Constitution, Gouverneur Morris, was the son of the third Lewis Morris, another prominent New York admiralty judge. Lewis Morris fathered a total of nine children, including Gouverneur. As illustrated by the Morris family tree above, Lewis and his first wife, Katryntje Staats, had three sons together. Fifteen years after Katryntje passed, Lewis married Sarah Gouverneur, Gouverneur’s mother.

Sarah gave birth to one son, Gouverneur, and four daughters. While the details are lost to history, it is clear that family friction existed between one or more of the children of Lewis’ first marriage and Sarah. Given the fact that Chief Justice Richard Morris subsequently sued Sarah, his stepmother, one can speculate that Richard may have been a source of the bitterness in the years preceding Lewis’ death.

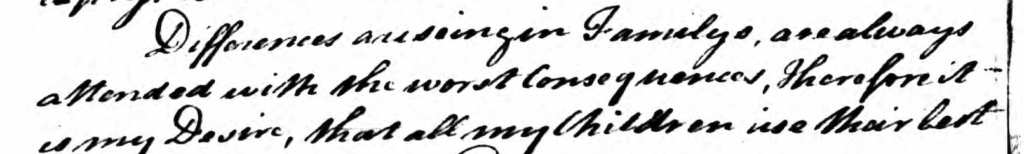

Lewis Morris was prescient when he wrote his will in 1762. As much as Lewis sought to avoid it, the will anticipated family conflict after his death. In his will Lewis wrote that family quarrels destroy families as certainly as civil wars overturn governments:

Differences arising in families are always attended with the worst consequences. Therefore it is my desire that all my children use their best endeavors to cultivate a good understand with each other that be dutiful to their Mother (which although she is a mother-in-law to some of them) has done them equal justice; but if they should be so unhappy as to differ with each other, let them as soon as possible reconcile themselves, for family quarells destroy families, as certainly as civil war overturn government.

Little could Lewis have known how deep these family divisions would become during the Revolutionary War. Arguably no family better represents the schism between loyalists and patriots than the Morris family.

While not the focus of this blog post, Gouverneur Morris and his half-brother, Lewis Morris, were signers of America’s foundational documents. By contrast, their brother, Staats Long Morris, was a British General and member of Parliament. Other members of the extended family, including brother-in-law Isaac Wilkins, were leading loyalists. A separate post will describe Isaac Wilkins’ plight as a loyalist. After the Revolutionary War Isaac and Gouverneur’s sister, Isabella, fled to Canada. Governor Morris’ mother, Sarah, who was in her sixties when the war began, sided with the king.

Sarah Morris’ Loyalist Claim intersects with Morris family probate litigation

After the Treaty of Paris concluded the Revolutionary War, the American Loyalist Claims Commission was established to examine claims for losses sustained by those who were loyal to the king (loyalists). It was recently discovered that attorney Alexander Hamilton assisted and/or represented Sarah Morris with her loyalist claim in or around October of 1783. Sarah’s “Morrisania Claim on the British Government” was submitted to London seeking relief for damages to the Morrisania estate during the Revolutionary War.

Part 1 began by analyzing a single orphaned page in the Hamilton Papers at the Library of Congress. After comparing the orphaned page at the Library of Congress with the Morrisania claim at Columbia University, it became immediately evident that the fragmentary draft in Hamilton’s handwriting was in fact page 13 of the full “loyalist claim” submitted on behalf of Sarah Morris.

Fortunately, the British kept excellent notes and detailed records documenting the thousands of “loyalist claims” seeking relief for damages sustained during the war. No Hamilton scholar had ever suggested that Hamilton was involved the Morrisania loyalist claim. Yet, the records filed in London are verbatim copies of the orphaned page in the Hamilton Papers at the Library of Congress and the full loyalist claim in the Gouverneur Morris Papers at Columbia.

Things get even more interesting when Sarah Morris’ entire loyalist file, including affidavits, exhibits and related legal filings are examined. The University of New Brunswick houses the Loyalist Collection which consists of over 3200 microfilm reels and 700 microfiche.

The extensive Morrisania file in the Loyalist Collection offers unparalleled access to primary sources which likely have never been previously examined by Morris or Hamilton scholars. Among the voluminous Morrisania records contained in the Loyalist Collection are legal files from the inter-related Morris probate litigation. It is here where evidence of the Morrisania arbitration by Clinton and Schuyler was uncovered.

Sarah died in 1786. Dowager Sarah Morris had been the holder of a “life estate” interest in Morrisania manor for years. In his will, Lewis Morris granted his wife Sarah control over Morrisania during her lifetime. Lewis died in 1762 when Gouverneur was only 10 years old. Before his death, Lewis anticipated hostilities within the family after his passing.

Morris Family Probate Litigation

In late 1785 Richard Morris – the Chief Justice of the New York Supreme Court – sued Sarah on behalf of himself, his sister Mary, and brother, Staats Long Morris. Richard sought an accounting in Chancery Court of Sarah’s management of the manor. This lawsuit by Gouverneur Morris’ half-brother intersected with Sarah’s loyalist claims which were still pending in London.

Sarah died in January of 1786. Upon her death, Gouverneur Morris and Samuel Ogden were appointed executors of the estate of Sarah Morris. Despite the death of his step-mother, Richard Morris felt the need to press claims as the executor of his father’s will.

According to Lewis Morris’ will, Staats Long Morris would conditionally inherit Morrisania upon Sarah’s death. The condition imposed on Staats to inherit Morrisania was the requirement that he pay £7000 to be shared among his siblings. Even though Richard was not entitled to inherit the Morrisania estate, Richard proceeded to refile the suit against Gouverneur Morris and Samuel Ogden, who were Sarah’s executors. This litigation which began in 1785 was finally resolved in 1787, with Gouverneur Morris’ acquisition of the Morrisania estate.

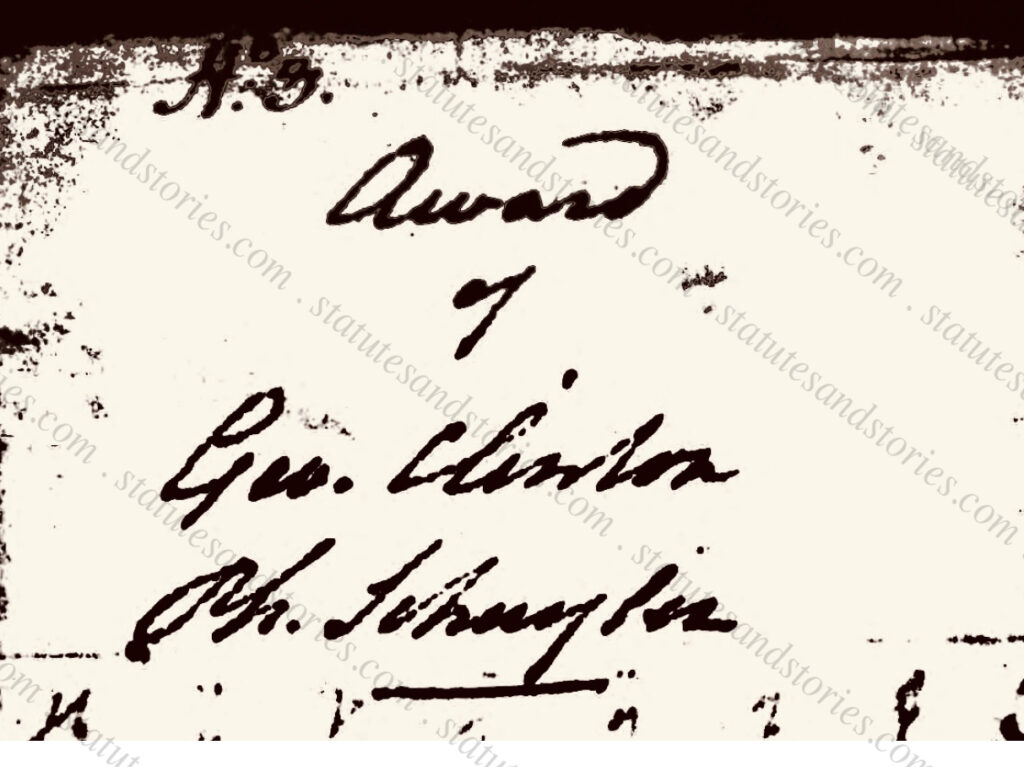

Arbitration Award

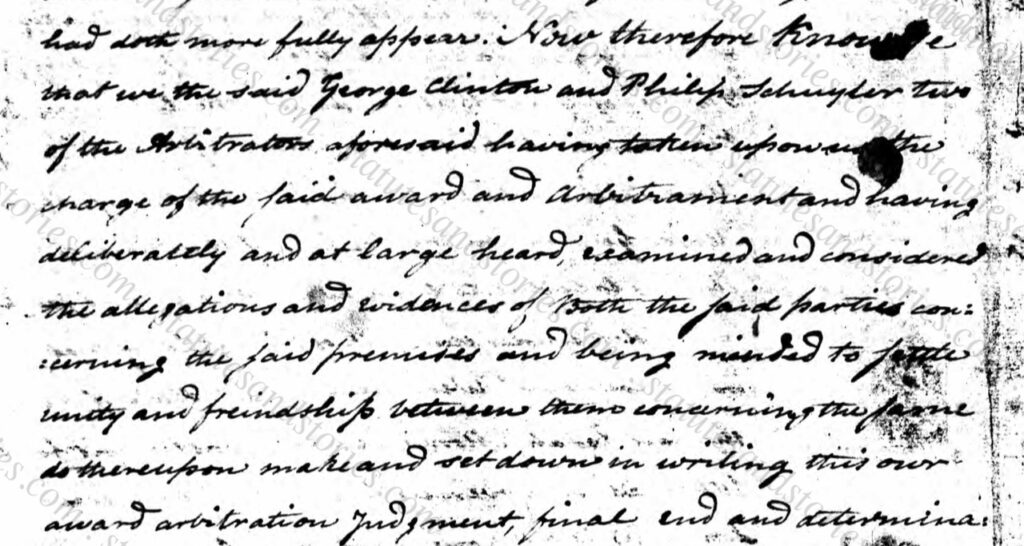

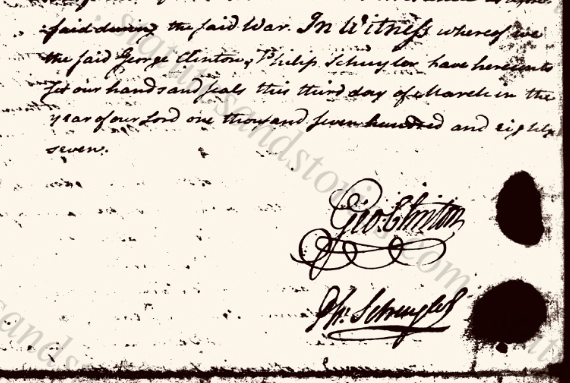

The arbitration award which resolved the Morris family dispute was signed on March 3, 1787. The award begins by summarizing the facts of the case and quoting from Lewis Morris’ will. The award also describes the pending probate litigation.

Three arbitrators were selected for the case: Governor Clinton, Senator Schuyler, and John Jay. Arguably these were the three most famous politicians in New York. The parties submitted themselves “to be bound each to the other” upon a written decision of two of the named arbitrators. A hearing was held on February 8, 1787.

As set forth in the arbitration award:

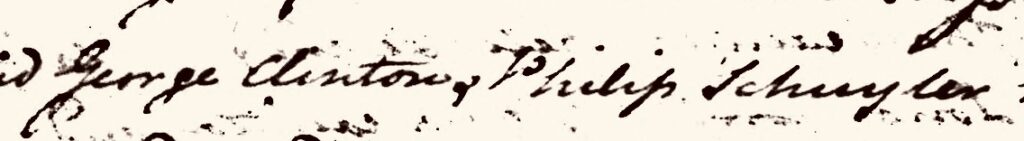

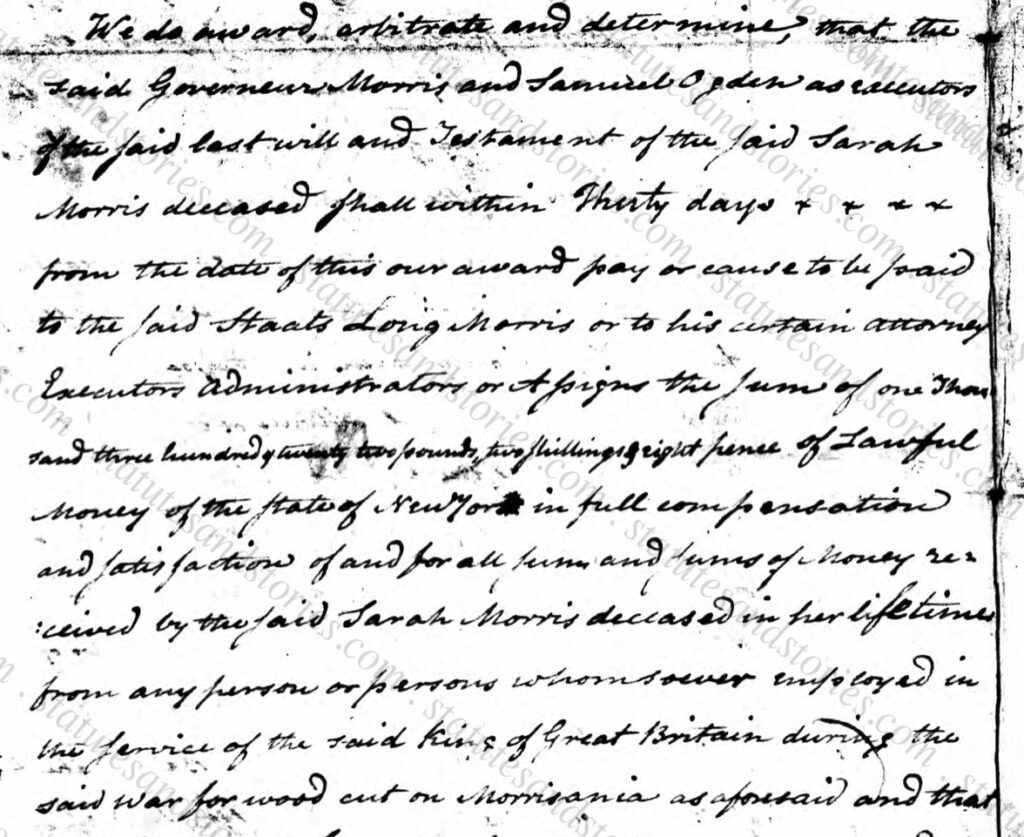

Now therefore knowing that we the said George Clinton and Philip Schuyler…having deliberately and at large heard, examined and considered the allegations and evidences….and being minded to settle unity and friendship between them…

After summaring the case, Clinton and Schuyler held that Gouverneur Morris and Samuel Ogden would have 30 days to pay £1,322 pounds, 2 shillings and 8 pence to Staats Long Morris in full satisfaction of and for all sums received by Sarah Morris from the government of Britain during the war “for wood cut on Morrisania.” The award further provided that Gouverneur Morris and Samuel Ogden, as executors of Sarah Morris, would release and quitclaim to Staats Moris any remaining claims against the British government.

The arbitration award of £1,322, 2 shillings and 8 pence was very specific. This amount can be traced to the loyalist claim drafted by Hamilton in 1783. With Sarah’s permission during the war, the British army used Morissania as a base of operations. Sarah also sold livestock and timber to the British. While Sarah’s loyalist claim drafted by Hamilton sought £8,309, the petition admitted that Sarah had been paid £1,341 and nine shilling by British quartermasters at various times during the war.

What explains the slight difference between the £1,322.2.8 awarded by Clinton and Schuyler and the £1,341.9 paid by the British during the war? The answer is unclear. One can speculate that this £20 pound difference may have been the fees charged by Clinton, Schuyler, and Jay?

Once these sums were liquidated by the arbitration award, Gouverneur Morris was able to borrow funds to purchase the eastern portion of Morrisania from Staats Morris. Living in Britain, Staats had no real desire to inherit the Morrisania estate. Staats, however, was in the best position to collect on the Loyalist claim drafted by Hamilton in 1783.

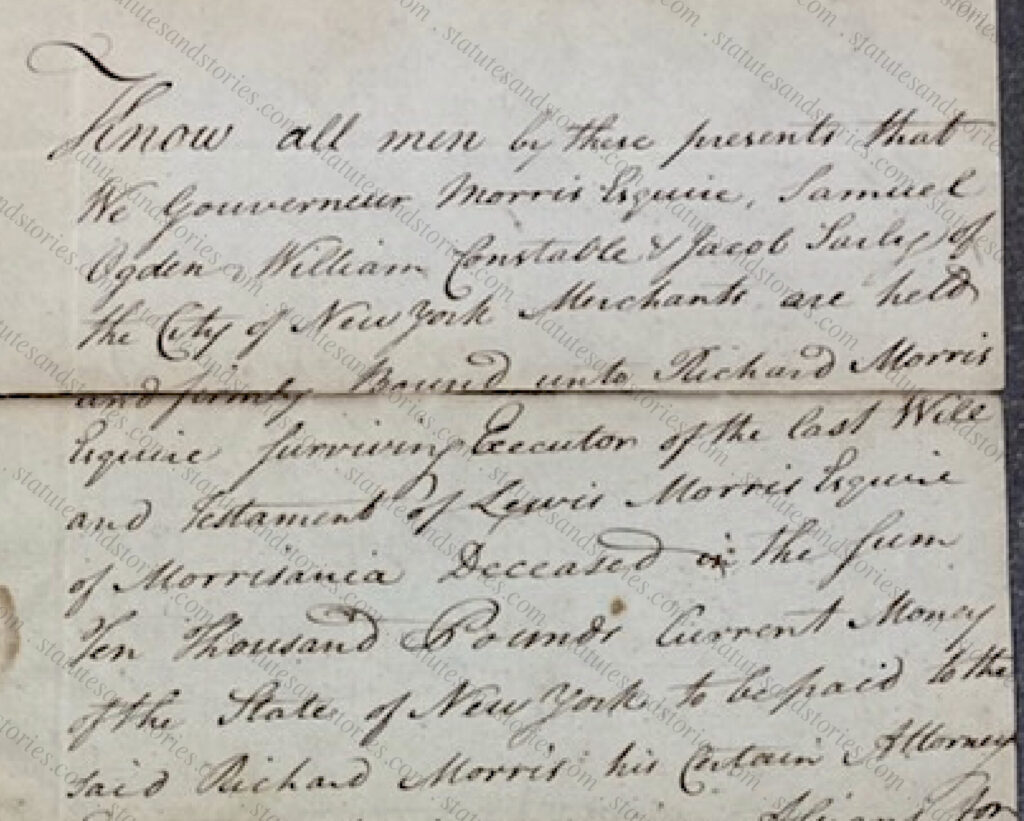

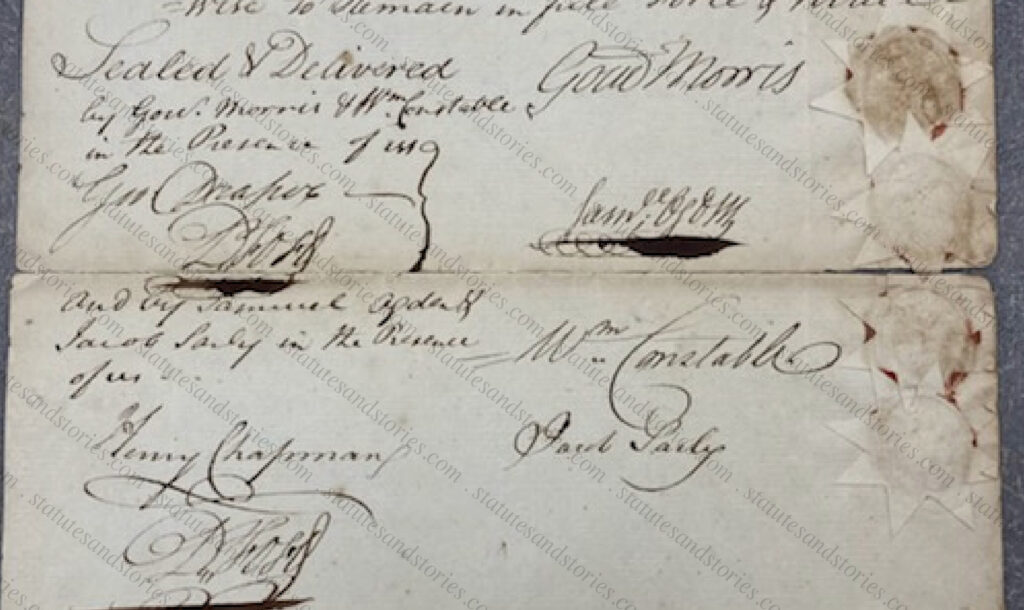

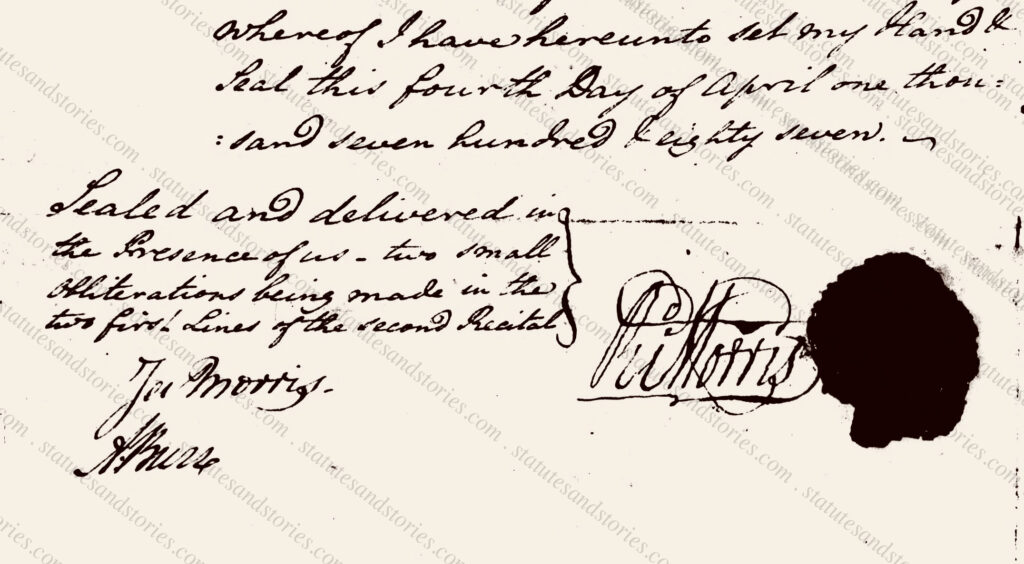

In April of 1787 Gouverneur purchased Morrisania from Staats for £10,000 pounds. Two thousand pounds were owed to Gouverneur as his inheritance. The balance was loaned to Gouverneur and secured by a £10,00 bond by his business partner and friend, William Constable. The transaction was also made possible by the willingness of Gouverneur’s sisters to accept installments on their £700 shares.

Copied below is the £10,000 bond, which was obtained from archives at Yale University.

The exhaustive legal filings contained in the Loyalist Collection document the complex transactions required to finalize the arbitration award and Gouverneur’s purchase of the eastern portion of Morrisania.

After their father’s death two decades earlier, Lewis Morris, the oldest son, inherited the title manor lord along with western 500 acres of the Morrisania estate. Sarah held a “life estate” in the 1,400-acre eastern portion of the estate. Gouverneur would purchase the “reversion” of the Morrisania estate from his half-brother, Staats Morris, in 1787. Richard and Gouverneur did not inherit any land, only monetary bequests, which may also explain Richard’s litigiousness.

Gouverneur Morris biographer Max Mintz unpacks the legal transactions that were formalized on April 4, 1787:

On that day Gouverneur, Staats, and Richard met and signed three documents. One was the transfer of the estate from Staats to Gouverneur. A second was a mortgage granted by Gouverneur to Staats for £3,000 at 5 percent interest, payable on April 1, 1792. The third was a mortgage by Gouverneur to Richard for £2,100, payable on January 4, 1788.

With access to the recently revealed records in the Loyalist Collection, it is now also clear that the Mossisania case file is a veritable who’s who of the New York judiciary and bar at the time:

- Gouverneur Morris purchased Morrisania from Staats Morris and paid off Staats’ obligations to Richard and their sisters;

- Richard Morris, as the executor of patriarch Lewis Morris, confirmed “receipt” of £7,000 pounds received from Staats Morris. The document is witnessed by Aaron Burr, which suggests that Burr may have been representing Chief Justice Richard Morris in the case;

- Gouverneur Morris and Samuel Ogden signed a release and quitclaim as the executors of Sarah Morris, releasing all claims of Sarah on the government of Great Britain to Staats who lived in England;

- Richard Morris, the Chief Justice of New York, acknowledged that the release was voluntary and that he had carefully inspected the written instrument which was free from any material erasures or errors;

- Judge John Hobart, a Judge of the Supreme Court of the Judicature of New York, also signed an acknowledgment which was also filed in the deed book of the Secretary’s Office of the State of New York.

As described by Richard Broohiser, “Morris was not lord of a manor, but he had 1,400 acres, with river views. To keep it…he would have to continue working at his many ventures.

UNDER CONSTRUCTION…