Hamilton’s arrival in Philadelphia: New Discoveries (Part 1)

Historians of the framing of the Constitution have long downplayed Alexander Hamilton’s involvement at the Constitutional Convention. Indeed, Hamilton biographers commonly express surprise at his underwhelming performance in Philadelphia. Recent discoveries, however, justify a re-examination of Alexander Hamilton’s behind-the-scenes contributions.

As described below, Hamilton arrived in Philadelphia earlier than previously recognized. Moreover, we now know that he sought reimbursement for a total of 76 days, including travel time. This and other new evidence suggests that Hamilton was conferring with the Virginia and Pennsylvania delegations as early as May 15 or 16. It is now becoming clear that Hamilton was also collaborating with Philadelphia delegate Gouverneur Morris, well before the Convention officially began on May 25th.

James Madison did not begin taking notes at the Constitutional Convention until May 25, the first day that an official quorum was present. Relying on Max Farrand’s seminal work, The Records of the Federal Convention, historians take for granted that Alexander Hamilton first attended the Convention beginning on May 18, 1787. In 1911, Farrand assembled a list of delegate attendance based on “available data.” With new information that has recently come to light, it is time to reevaluate commonly held assumptions about Hamilton’s limited role, originally rooted in Farrand’s limited data from 1911. Click here for a discussion of Hamilton’s activities at the Constitutional Convention.

By way of example, Ron Chernow asserts that “Hamilton arrived in Philadelphia on May 18, 1787, and joined other delegates at the Indian Queen Tavern on 4th Street.” William Stern Randall, another Hamilton biographer, similarly records that, “arriving in Philadelphia in the blistering first burst of a Philadelphia summer on May 18, 1787, Alexander Hamilton checked into the Indian Queen tavern on Third Street between Market and Chestnut, a short walk to Independence Hall.” According to historian Carol Berkin, “[o]n Friday, May 18, Alexander Hamilton at last arrived and immediately threw himself into the frenzy of caucusing which now filled the days of most of the delegates.” But what if these historians are working from an incorrectly truncated calendar?

Relying on this conventional wisdom that Alexander Hamilton did not arrive in Philadelphia until May 18, historians assume that Alexander Hamilton did not participate in early discussions between the Virginians and Pennsylvanians. As set forth below, this Conventional understanding is arguably wrong. Moreover, Hamilton may not have checked into the Indian Queen at all. Rather, as discussed in Part II (pending), he may have been staying at Ms. Dally’s boarding house with Gouverneur Morris.

The following recently discovered/re-discovered records require re-assessment of the traditional narrative that Hamilton did not play a meaningful role in the early deliberations between the Virginia and Pennsylvania delegations:

- Hamilton’s reimbursement records discovered in the New York State Archives in Albany in 2021 (see image above);

- the journals of the Society of the Cincinnati reflecting Hamilton’s attendance at 9:00 a.m. on May 17;

- a May 16 report in the Pennsylvania Packet newspaper indicating that Hamilton had “arrived” in Philadelphia; and

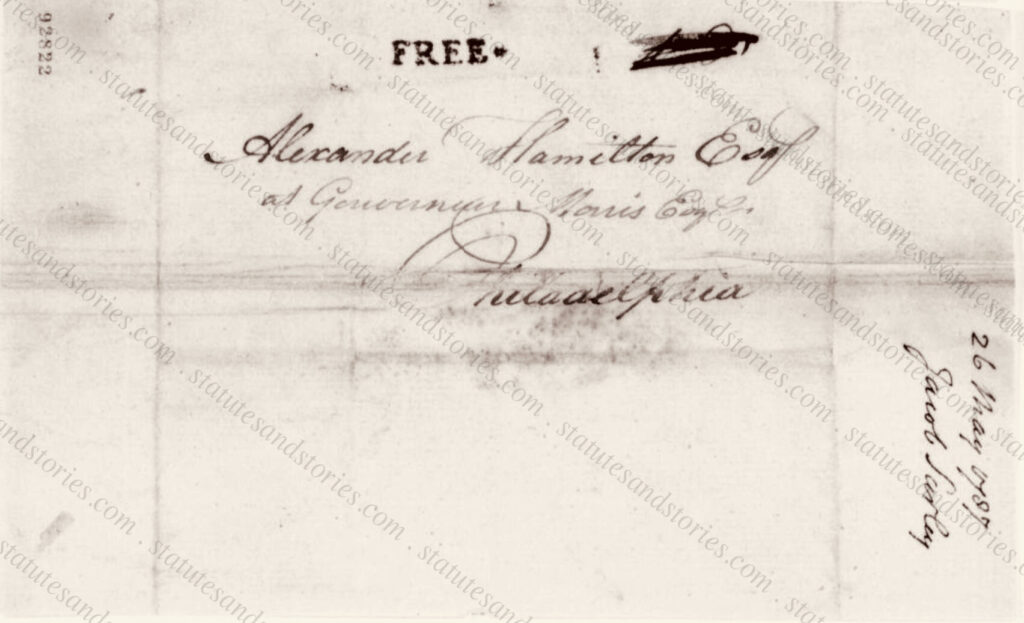

- Hamilton’s Philadelphia mailing address “at Gouvernuer Morris” in May of 1787 (pictured below), which has been entirely overlooked by historians.

This interpretation is fully consistent with other extant records, including George Washington’s diary entries for May, 1787. Hamilton’s expanded role in the days preceding the Convention also aligns with early correspondence by Washington, Mason and Franklin.

“The delay that produced a revolution”

The report of the Annapolis Convention called for the Constitutional Convention to convene on May 14, the second Monday in May. Yet, when George Washington, James Madison and the other punctual members of the Virginia delegation arrived at the Pennsylvania State House (now known as Independence Hall) on May 14, they were disappointed. The only other state in attendance at the scheduled start date was Pennsylvania, the host of the Convention. The required seven state quorum would take almost two more weeks to arrive.

Historian Richard Beeman in the book Plain Honest Men makes the argument that the Virginians and Pennsylvanians made good use of this delay. For Beeman, the eleven-day interval between May 14 and May 25 was a “wonderful, serendipitous gift.” In a chapter entitled, “The delay that produced a revolution,” Beeman writes that:

Although it appeared to Madison an inauspicious beginning, in fact, the combination of bad weather and sloth that delayed the opening of the Convention would provide him with an invaluable opportunity to build support for the dramatic reforms that he sought.

In particular, Beeman suggests that the Virginians and Pennsylvanians were the ones “whose conversations and conclusions before the Convention would do the most to influence the eventual outcome.” Beeman explains that “[i]f there was one other group at the Convention likely to be receptive to Madison’s plan for scuttling the Articles of Confederation and substituting in its place a truly “national” government, it was the Pennsylvanian delegation.” But what if another kindred spirit was participating in these deliberations?

Agreeing with Beeman, Ed Larson writes that by “[h]oldng the dinner on May 16 limited it mainly to delegates from Virginia and Pennsylvania – but that proved fortuitous.” Washington, Franklin and their colleagues from Virginia and Pennsylvania thus took advantage of the delay to formulate the Virginia Plan. By attending these early sessions with their Virginia and Pennsylvania colleagues, Larson writes, “Franklin and Washington were present at the creation of the modern American government.” But who else was in the room?

Beeman theorizes that the two Pennsylvanians most important in these early deliberations were fellow lawyers Gouverneur Morris and James Wilson. According to Beeman:

One looking for the origins of the idea of the American presidency as a strong symbol of a unified nation need look no further than the ideas of Gouverneur Morris and James Wilson, presented during those seven days of informal discussion. And it didn’t hurt that George Washington, the most powerful exemplar of those ideas, was present for those discussions.

Beeman is not alone in recognizing Madison, Morris and Wilson’s central role in Philadelphia. Larson concurs that the Virginia and Pennsylvania delegations “contained the three delegates with the most advanced ideas on the topic,” Madison, Morris and Wilson.

In the book, 1787: The Grand Convention, Clinton Rossiter divides the fifty-five framers into eight categories ranging from “Principals” to “Inexplicable Disappointments.” Rossiter elevates only four names in the highest category of Principal: Madison, Morris, Wilson and Washington. At the other end of the spectrum, Rossiter concludes that Alexander Hamilton was “[f]ar and away the most disappointing man” even though the “brilliant” New Yorker “had done so much to bring the Convention to life.” For Rossiter, the “wide gap” between the possible and the actual comes as “an unpleasant shock” when grading Hamilton’s performance.

But what if Hamilton had been participating in these early discussions in May? As described in Part II (pending), newly emerging evidence suggests that Hamilton was coordinating with Gouverneur Morris prior to May 25. If so, was the delegate who was the biggest “disappointment” in fact working closely together with one of the most esteemed “principals”?

Finding Hamilton

Modern historians routinely cite to George Washington’s diary entry on May 18 which evidences that Alexander Hamilton and fellow New York delegate Robert Yates “appeared on the floor today.” Nevertheless, Washington’s diary entry doesn’t rule out Hamilton’s earlier appearance in Philadelphia. As set forth below, Hamilton may have been in Philadelphia as early as May 15 or 16.

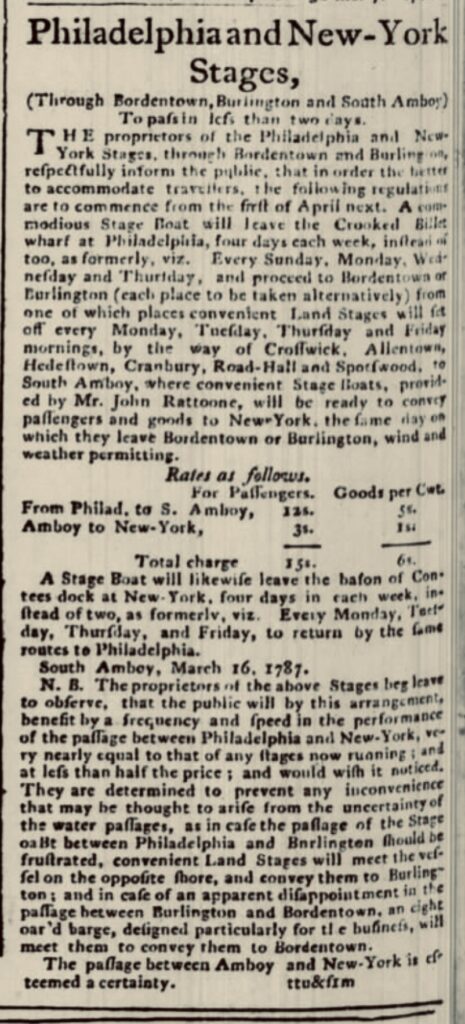

Indeed, recently discovered financial records confirm that Alexander Hamilton was reimbursed for a total of seventy-six days for his work at the Constitutional Convention. He was paid a total of 121 pounds and 12 shilling for “76 days attendance” at the Convention, including coming and going “three several times.”

While Hamilton was very specific about the 76 days of total attendance (including three trips to Philadelphia), he did not specify which particular days he attended the Convention. Madison’s notes record Hamilton’s attendance from May 25 to June 29, August 13, and September 6 – 17. This means that a potential “Hamilton sighting” in July is not included in Hamilton’s 76 day tally.

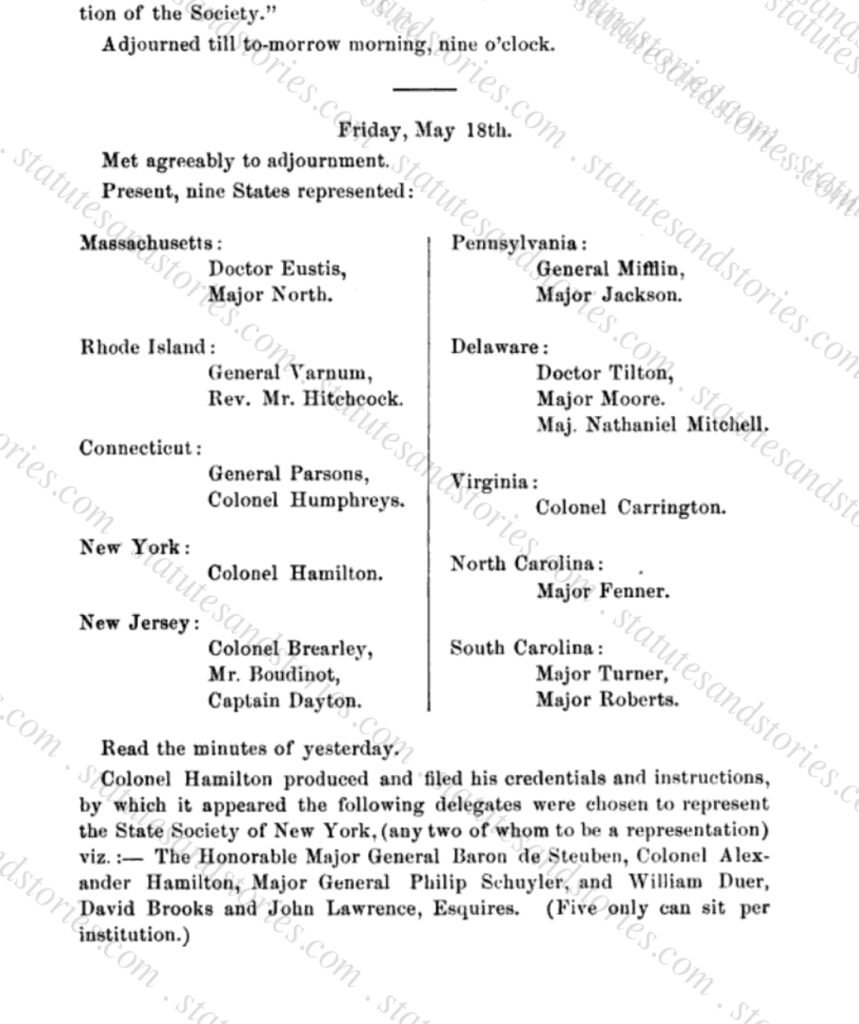

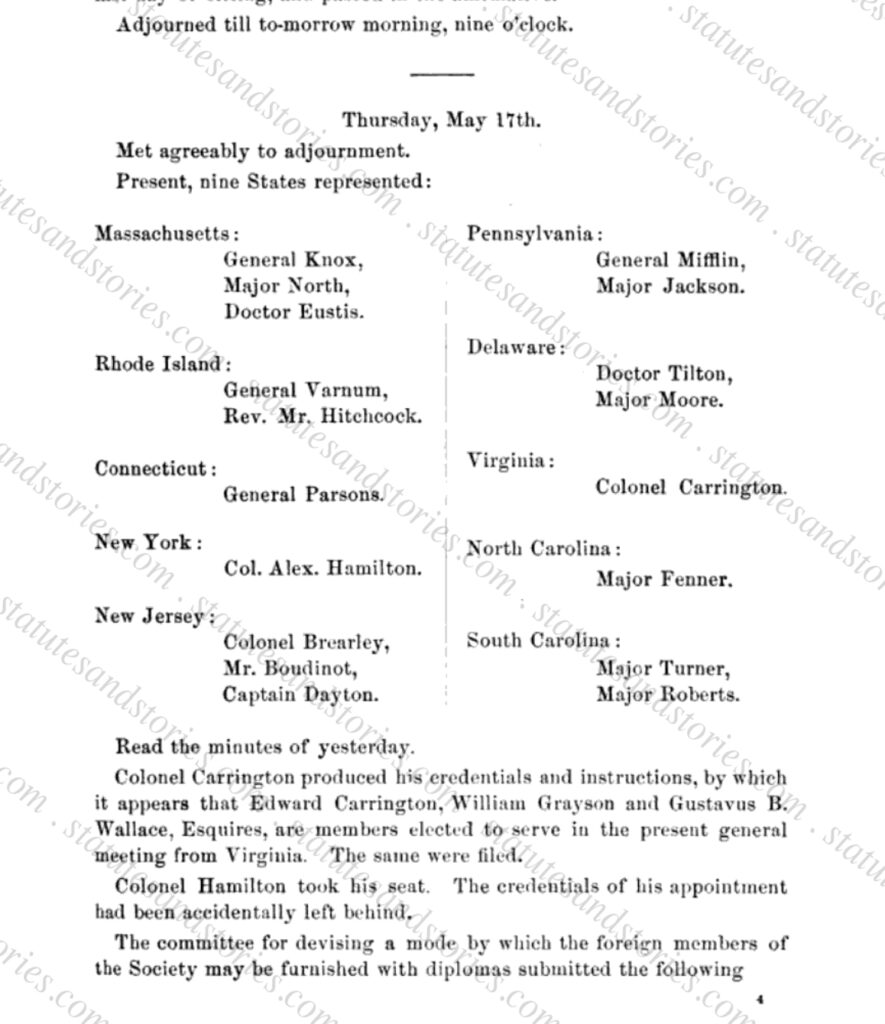

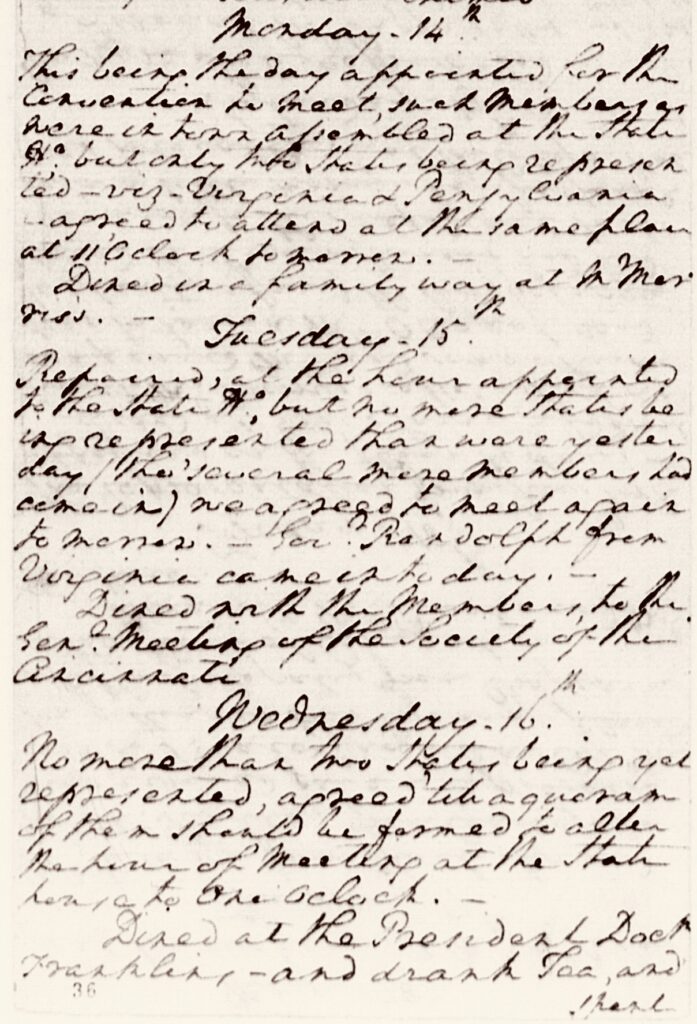

The first definitive record of Hamilton’s arrival in Philadelphia, interestingly, is the journal of proceedings of the Society of the Cincinnati. When Professor Syrett compiled the Hamilton Papers in the 1960s, he included an excerpt from the Proceedings of the General Society of the Cincinnati, which preceded the Constitutional Convention. This excerpt indicates that Hamilton filed his credentials on May 18, as a delegate from New York at the Philadelphia meeting of the Cincinnati. The May 18 excerpt is pictured below.

Syrett does not mention, however, that Hamilton also attended the Cincinnati meeting on May 17. According to the May 17 journal, Hamilton took his seat on May 17 but “accidentally left behind” his credentials. Thus, Hamilton was undoubtedly in Philadelphia on Thursday, May 17. The journal of the Cincinnati also records that meetings were consistently scheduled to begin at 9:00 every morning. As a result, it is safe to assume that Hamilton had arrived in Philadelphia prior to 9:00 on May 17.

Dinner at Benjamin Franklin’s on May 16

Is it possible that Hamilton may also have attended an important dinner at Ben Franklin’s house on May 16? As described below, this possibility cannot be ruled out. If so, Hamilton may have been at an early meeting of the “principals” when the Virginia and Pennsylvania delegations began to meet each other socially.

Ben Franklin famously entertained assembled Convention delegates on the evening of May 16 at his newly expanded grand dining room. We know about the dinner from a letter Franklin wrote on May 18 to Thomas Jordan, a friend who had supplied the cask of imported porter (a dark beer) that was opened that evening. Franklin’s letter describes his guests as an “assemble des notables” who were attending the Convention, but Franklin doesn’t identify any by name.

According to Franklin, his guests were “some of the principal people from the several states of our confederation.” Thus, Franklin’s letter neither confirms nor rules out Hamilton’s attendance. Yet, the use of the phrase “several states” suggests that delegates from more than just Pennsylvania and Virginia may have attended the dinner. Moreover, Hamilton was a leading voice calling for the Constitutional Convention. If Hamilton was present at the dinner, Franklin could easily have considered him among the “principal” leaders from New York.

Richard Beeman opines that dinner at Franklin’s – and the cask of porter that they drank – may have been a signature moment preceding the Convention. As imagined by Beeman, while the Virginia and Pennsylvania delegations “had met briefly from May 14 to 16, the dinner at Franklin’s house that night, and possibly the porter in particular, enabled the delegates most committed to a dramatic overhaul of the Articles of Confederation to coalesce.” Beeman further theorizes that this encounter helped reinforce the fact that Franklin and Washington both “made clear this support for a reinvigorated continental government.” Is it possible that Hamilton also attended this dinner?

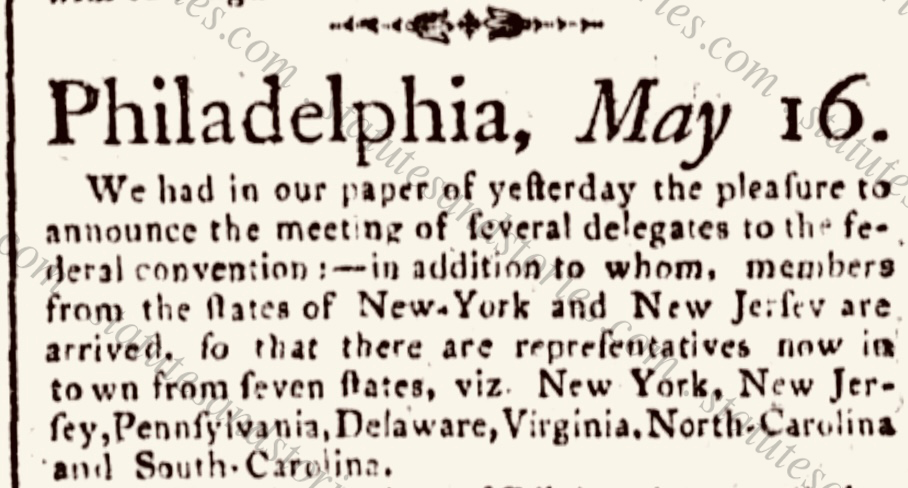

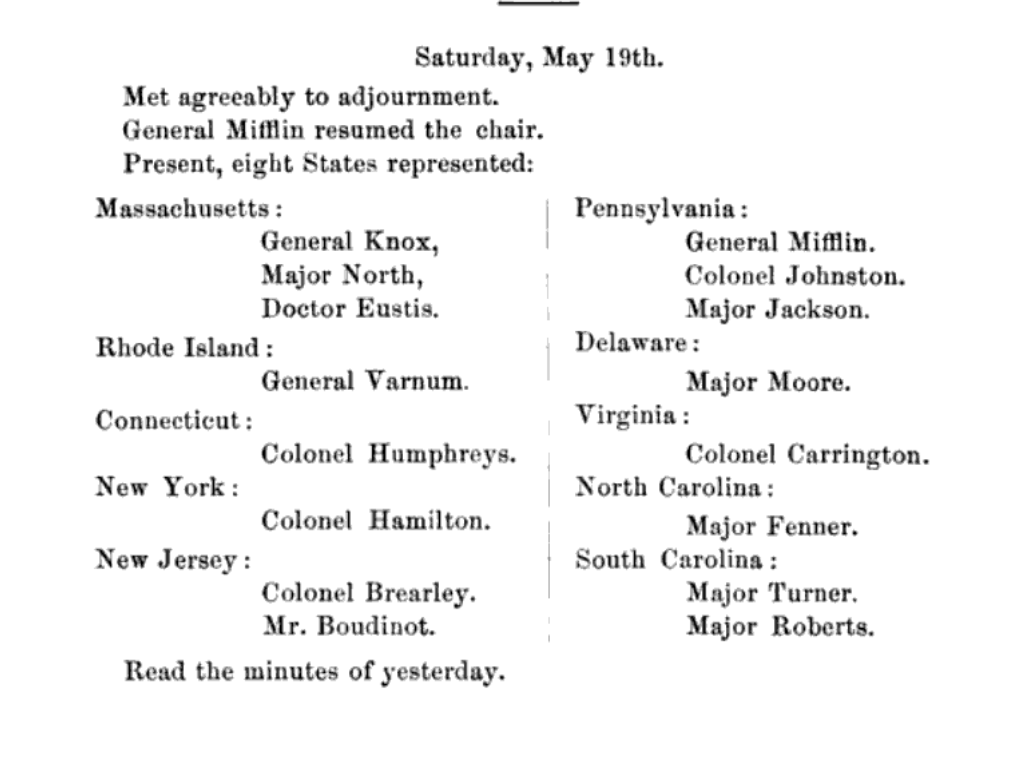

When Max Farrand assembled his seminal work, The Records of the Federal Convention, he included an excerpt from the Pennsylvania Journal and Weekly Advertiser identifying the names of the delegates who had arrived at the Convention on Saturday, May 19. Presumably Farrand did not have access to any earlier newspaper reports evidencing delegate arrival or he would have published them. Copied below is a very instructive newspaper report appearing in the Pennsylvania Packet dated May 16. Importantly, this contemporaneous primary source is compelling evidence that Hamilton was in town as early as May 16.

Washington’s diary

George Washington kept a daily diary throughout his life. The 51 volumes, not surprisingly, offer an important window into Washington’s thinking and daily activities. Washington’s diary from the summer of 1787 is enormously helpful to understand his schedule and serves as one of the few primary sources – while imperfect – to track delegate attendance prior to May 25th.

As a general rule, historians have read Washington’s diary to suggest that Hamilton first arrived in Philadelphia on May 18. In so doing, historians discount any consultative role that Hamilton may have played in the formulation of the Virginia Plan with Madison and the other Virginian delegates. Washington’s diary entry for May 18 merely indicates, however, that “[t]he representation from New York appeared on the floor today.”

It is submitted here that Washington was merely indicating that “the representation from New York” appeared on “the floor” of the Convention on May 18. In other words, it is entirely possible that Hamilton was in attendance in Philadelphia meeting with delegates prior to May 18. This explanation posits that Washington was not referring to individual delegates but rather to state delegations. Thus, Hamilton could have been present prior to May 18. It would have taken the arrival of fellow New York delegate Robert Yates to satisfy the two member quorum requirement, which Washington recognized on May 18.

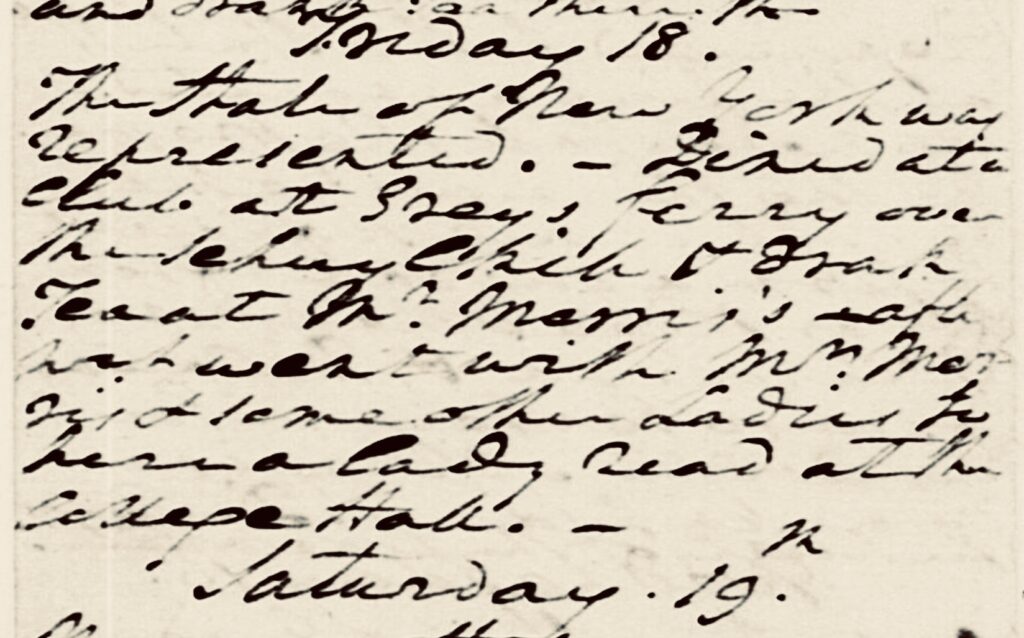

Other diary entries support this interpretation that Washington was generally only describing state delegations, not individual delegate attendance. For example, Washington’s diary entries for May 14, 15 and 16 note the following:

- Monday 14th. This being the day appointed for the Convention to meet, such Members as were in town assembled at the State Ho[use]; but only two States being represented—viz.—Virginia & Pensylvania—agreed to attend at the same place at 11 ’Oclock to morrow.

- Tuesday 15th. Repaired, at the hour appointed to the State Ho[use], but no more States being represented than were yesterday (tho’ several more members had come in) we agreed to meet again to morrow. Govr. Randolph from Virginia came in to day. (emphasis added) Dined with the Members, to the Genl. Meeting of the Society of the Cincinnati.

- Wednesday 16th. No more than two States being yet represented, agreed till a quoram of them should be formed to alter the hour of Meeting at the State house to One o’clock. Dined at the President Doctr. Franklins and drank Tea, and spent the evening at Mr. Jno. Penns.

Accordingly, it is submitted that Washington’s diary should only be read as referring to the attendance of functional delegations – which he calls “representations” – on the “floor” of the convention. Thus, Washington’s diary does not rule out Hamilton’s attendance at Franklin’s dinner party on May 16. Indeed, Washington’s diary allows for the possibility that Hamilton was in Philadelphia as early as May 15 when “several more members had come in.”

Washinton’s letter to George Augustine Washington

George Washington’s diary entries are properly evaluated alongside his letter of May 17 to his nephew, George Augustine Washington. Importantly, Washington’s letter to his nephew provides strong evidence that Hamilton was in fact in Philadelphia no later than May 17:

After short stages and easy driving, I reached this City on Sunday afternoon. Only 4 states—viz. Virginia, South Carolina, New York and the one we are in, are as yet, represented; which is highly vexatious to those who are idly, & expensively spending their time here.

By comparing Washington’s diary with his May 17 letter to his nephew, it is possible to surmise that Yates (or Hamilton) were not in attendance at the Convention on the morning of the 17th. We know, for example, that Hamilton was attending the Society of the Cincinnati meeting at 9:00 on the 17th. Yet, because New York is listed by Washington as one of four states as yet “represented” in his letter, it is possible that Yates arrived later during the day on the 17th. If so, Hamilton may well have been in Philadelphia several days prior to Yates’ arrival when the “representation” of New York eventually obtained a quorum.

This interpretation is also supported by Washington’s May 20 letter to Arthur Lee. Expressing his frustration with the slow pace of the Convention, Washington admitted that “[t]hese delays greatly impede public measures, and serve to sour the temper of the punctual members, who do not like to idle away their time.” Describing the states that had arrived, Washington reported that, “[n]ot more than four states were represented yesterday.” In other words, Washington wasn’t taking a head count of individual delegates, but rather was focused on the arrival of state delegations required to obtain a quorum.

Dinner with the Cincinnati on the 15th?

According to George Washington’s diary on May 16, the delegates at the Constitutional Convention decided “to alter the hour of Meeting at the State house to One o’clock” until a quorum eventually arrived in Philadelphia on May 25. Why change the time for the daily “meeting” at Independence Hall? What can we deduce?

By delaying the time of the Convention to 1:00, members of the Society of the Cincinnati could attend both meetings. The Cincinnati met regularly at 9:00 each morning. Sure enough, the following day the minutes of the Cincinnati record Alexander Hamilton’s attendance on May 17 at 9:00 am.

It is thus plausible that Hamilton missed the Cincinnati meeting on May 16 because he was attending the Constitutional Convention that morning. If so, perhaps Hamilton was the delegate on May 16 who proposed moving up the meeting time to 1:00, as described in Washington’s diary?

According to this theoretical timeline, Hamilton could have attended both the dinner with Washington and the Cincinnati on May 15 and the dinner with Franklin and the Virginia & Pennsylvania delegates on May 16.

Mason’s letter of May 20

George Mason was a well-respected member of the Virginia delegation. Among other things, he was a principal drafter of the Virginia Declaration of Rights and the Fairfax Resolves. While waiting for the Convention to achieve a quorum Mason wrote detailed letters which are also very instructive. As described below, Mason’s letters likewise do not rule out Hamilton’s early arrival in Philadelphia.

Mason’s letter dated May 20 to his son, George Mason, Jr., provides in pertinent part:

Upon our arrival here on Thursday evening, seventeenth May, I found only the States of Virginia and Pennsylvania fully represented; and there are at this time only five – New York, the two Carolinas, and the two before mentioned. All the States, Rhode Island excepted, have made their appointments; but the members drop in slowly; some of the deputies from the Eastern States are here, but none of them have yet a sufficient representation, and it will probably be several days before the Convention will be authorized to proceed to business.

There is much to unpack in these opening sentences. Mason merely states that upon his arrival on May 17 he found only the states of Virginia and Pennsylvania “fully represented.” Based on the Society of the Cincinnati journals, it should be clear that Hamilton was in town on May 17th when Mason arrived.

Later in his letter, Mason explains the daily procedure while waiting for other deputies to arrive:

The Virginia deputies (who are all here) meet and confer together two or three hours every day, in order to form a proper correspondence of sentiments; and for form’s sake, to see what new deputies are arrived, and to grow into some acquaintance with each other, we regularly meet every day at three o’clock. These and some occasional conversations with the deputies of different States, and with some of the general officers of the late army (who are here upon a general meeting of the Cincinnati), are the only opportunities I have hitherto had of forming any opinion upon the great subject of our mission, and, consequently, a very imperfect and indecisive one….

The Cincinnati meeting lasted through Saturday, May 19. It makes perfect sense that the Virginia delegates would meet with the other delegations at 3:00. Why? Because Hamilton and several other Cincinnati members were attending the Cincinnati meeting. Among the members in attendance at the Cincinnati meetings were Colonel Hamilton, General Mifflin from Pennsylvania, and Colonel Brearly from New Jersey. Moreover, by meeting at 3:00, the delegates would have a better idea of which new delegates had arrived during the day.

Perhaps the most interesting part of Mason’s letter is his observations about some of the “prevalent” ideas being discussed among the “principal States.” Mason’s description of the content of the emerging Virginia Plan is not surprising. Nevertheless, his mention of “very eccentric opinions” is particularly noteworthy. Could Mason be referring to Hamilton’s ideas which were more radical than Madison’s Virginia Plan?

The most prevalent idea in the principal States seems to be a total alteration of the present federal system, and substituting a great national council or parliament, consisting of two branches of the legislature, founded upon the principles of equal proportionate representation, with full legislative powers upon all the subjects of the Union; and an executive: and to make the several State legislatures subordinate to the national, by giving the latter the power of a negative upon all such laws as they shall judge contrary to the interest of the federal Union. It is easy to foresee that there will be much difficulty in organizing a government upon this great scale, and at the same time reserving to the State legislatures a sufficient portion of power for promoting and securing the prosperity and happiness of their respective citizens; yet with a proper degree of coolness, liberality and candor (very rare commodities by the bye), I doubt not but it may be effected. There are among a variety some very eccentric opinions upon this great subject; and what is a very extraordinary phenomenon, we are likely to find the republicans, on this occasion, issue from the Southern and Middle States, and the anti-republicans from the Eastern; however extraordinary this may at first seem, it may, I think be accounted for from a very common and natural impulse of the human mind.

After a diligent search, it does not appear that historians have asked the following questions which attempt to connect the dots between Mason’s musings and Hamilton’s proposals. One can only wonder:

- Did Hamilton and Mason discuss Hamilton’s outspoken reasons for “making the several State legislatures subordinate to the national”?

- Was Mason merely referring to conversations with Madison when Mason describes giving the national government “the power of a negative” upon the states? Of course, the Hamilton Plan also had a federal “negative,” now known as a veto.

- When Mason admits that “it is easy to forsee that there will be much difficulty in organizing a government upon this great scale,” had he compared notes with Hamilton about anticipated opposition in New York? For example, did Mason and Hamilton discuss New York’s recent rejection of the proposed Impost of 1783, which was a precipitating cause which “begat” the Constitutional Convention?

- Does Mason’s phrase “very eccentric opinions upon this great subject” have anything to do with Hamilton? If not, which other delegates in attendance in Philadelphia on or before May 20 were circulating more radical ideas than the Virginia Plan?

While we may never know a definitive answer to these questions, it is certainly plausible that the Virginians, Pennsylvanians and Hamilton were conferring in earnest earlier than traditionally recognized by historians. If So Hamilton was “in the room where it happened” when the Virginia Plan was being formulated.

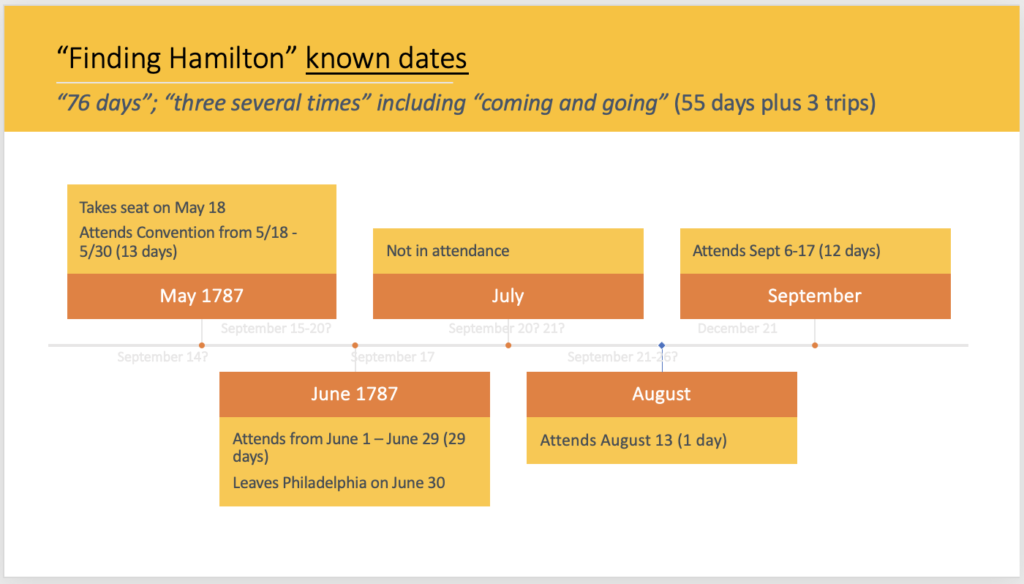

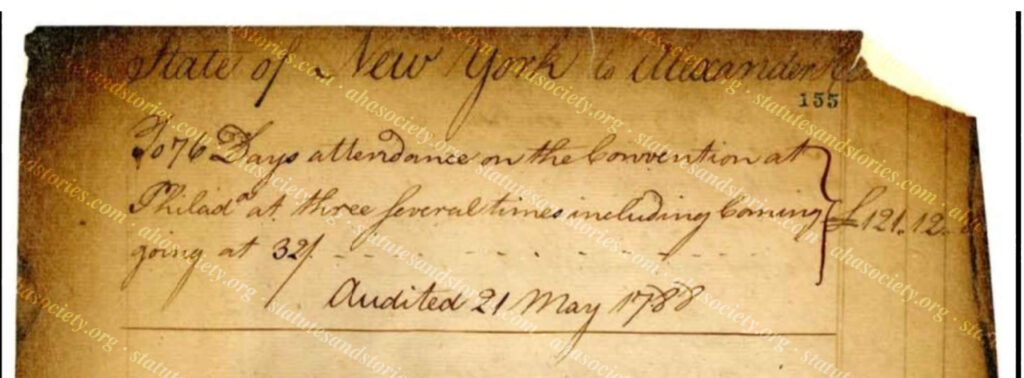

Copied below are two timelines of Alexander Hamilton’s calendar in 1787. The first timeline identifies the known dates when Hamilton attended the Constitutional Convention. The second timeline suggests a proposed Philadelphia arrival schedule, based on the “76 days” that Hamilton billed the state of New York. Timeline 2 theorizes that Alexander Hamilton arrived in Philadelphia on May 16, after departing New York on May 13. Alternatively, a May 12 departure date would use all of the 76 days, provided that Hamilton was billing three days for travel for each leg of the trip to and from Philadelphia. Note that three days for travel is a reasonable estimate based on the fact that Secretary Jackson departed the Convention on the morning of September 18 and arrived in New York on September 20 when he delivered the proposed Constitution to Congress.

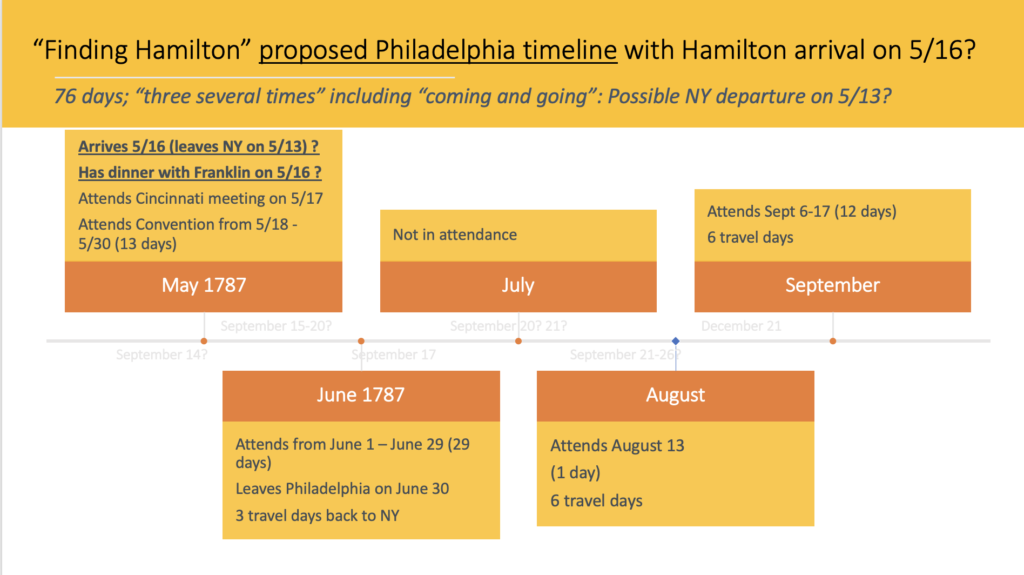

Pictured below are sample carriage and stage boat departure schedules between New York and Philadelphia. This advertisement and similar ads regularly appeared in the Pennsylvania Packet and other local newspapers in 1787. Interestingly, these expanded schedules began in April of 1787, just in time for the Constitutional Convention. The proprietors proclaimed that “the public will by this arrangement benefit by a frequency and speed in the performance of the passage between Philadelphia and New-York” at less than half of the prior price.

This post continues in Part II (pending) which discusses likely collaboration between Alexander Hamilton and Pennsylvania delegate Gouverneur Morris. Where did Hamilton and Morris reside during the Convention? Is it possible that Morris and Hamilton were plotting together in May, just as they would subsequently work together on the Committee of Style and Arrangement in September?

Additional reading and sources:

The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787, Vol III, edited by Max Farrand (1911)

Plain, Honest Men: The Making of the American Constitution, Richard Beeman (2009)

Miracle at Philadelphia, Catherine Drinker Bowen (1966)

A Brilliant Solution: Inventing the American Constitution, Carol Berkin (2002)

The Summer of 1787: The Men who Invented the Constitution, David O. Stewart (2007)