Was Alexander Hamilton’s father-in-law being sued by another New York delegate during the Constitutional Convention?

A long overlooked legal file from 1787 raises provocative questions about the New York delegation to the Constitutional Convention. After 235 years, the case of Henry Ten Eyck v. Philip Schuyler demonstrates that the relationship between Alexander Hamilton and his fellow New York delegates is far more complex than previously understood. Scholars are invited to assist with this continuing research project.

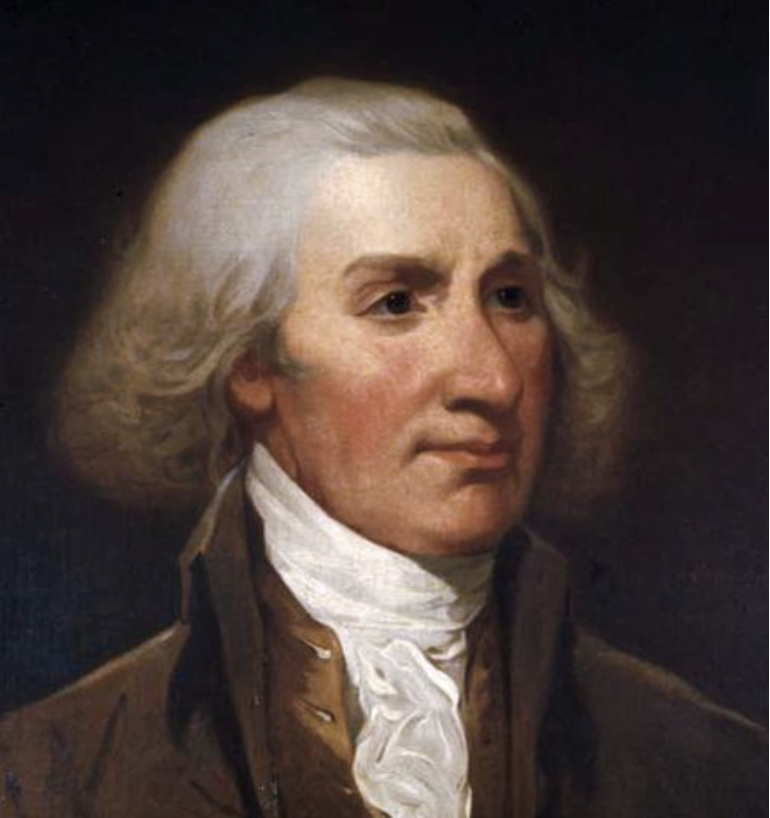

In 1787, Philip Schuyler was the defendant in the case of Henry Ten Eyck v. Philip Schuyler. Interestingly, Schuyler’s son-in-law, Alexander Hamilton, and fellow Constitutional Convention delegate, John Lansing, Jr., are both connected to the case. While the historic record is incomplete, it is clear that this case raises interesting, but as yet unanswered questions.

The case of Ten Eyck v. Schhuyler is not discussed in Julius Goebel’s four volume book, The Law Practice of Alexander Hamilton. Likewise, the case is not mentioned by any Hamilton biographers or in any histories of the Constitutional Convention. Nevertheless, the Ten Eyck v. Schhuyler case is crying out for scholarly analysis.

This article asks the following questions: Was Alexander Hamilton’s father-in-law being sued by attorney John Lansing in 1787, the year of the Constitutional Convention? Or was John Lansing representing Philip Schuyler in the case? Either way, the Ten Eyck v. Schuyler case has important lessons to teach.

Background about the New York delegation to the Constitutional Convention

On March 6, 1787, New York appointed three delegates to attend the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia. Alexander Hamilton was a well-known nationalist who had been advocating for a stronger central government for years. Yet, his two co-delegates, Robert Yates and John Lansing, were specifically chosen based on their opposition to Hamilton’s proposals. Thus, historians generally agree that the New York Legislature appointed Yates and Lansing to undermine Hamilton and protect the status quo.

At the Constitutional Convention states voted by delegation. As a result, Lansing and Yates effectively controlled the New York delegation. Hamilton would thus be repeatedly outvoted by Yates and Lansing on every issue. As described by Ron Chernow, rather than leading a united delegation, “Hamilton was demoted to being a minority delegate from a dissenting state.” Accordingly, the “chief catalyst for the convention” would be hamstrung by a hostile Governor and his anti-reform surrogates. Click here for a discussion of Hamilton’s role at the Constitutional Convention.

In the months preceding the Convention, James Madison evaluated each of the state delegations that would be sent to Philadelphia. In a March 18, 1787 letter to George Washington, Madison accurately described the challenges facing Hamilton at the Convention:

The deputation of N. York consists of Col. Hamilton, Judge Yates and a Mr Lansing. The two last are said to be pretty much linked to the antifederal party here, and are likely of course to be a clog on their colleague.

The size and composition of New York’s three-member delegation contrasted with the larger delegations sent to Philadelphia. Virginia, for example, sent a seven-member delegation which included arguably the most beloved American, George Washington. Pennsylvania’s delegation was led by Ben Franklin, the only American arguably more famous than Washington. Moreover, Virginia and Pennsylvania appointed their governors to lead their delegations.

Unlike other states, New York did not fully embrace the mission of the Convention. The New York legislature did not appoint its governor (George Clinton) or its most prominent citizens. According to Professor John Kaminski, New York’s three delegates were “respectable.” Kaminski notes that Chancellor Robert R. Livingston, Philip Schuyler, Lewis Morris, James Duane and the other “great manor lords” were not selected by New York as delegates. Likewise, New York did not appoint its most prominent attorneys or merchant captains (such as John Jay, Egbert Benson and Richard Harrison). Click here for a more detailed discussion of the plan to sabotage Hamilton at the Convention.

According to Kaminski, Hamilton’s reputation as a strong nationalist was well known going into the Convention. “Yates and Lansing, on the other hand, were thought to be opponents of any serious attempts to strengthen the general [federal] government,” particularly at New York’s expense. Famously, Yates and Lansing were the first delegates to depart the Convention in protest. As such, Yates and Lansing can be described as the first Anti-Federalists to reject the Constitution.

Not surprisingly during the ratification debates, the former colleagues led the opposing political campaigns. In 1788, Hamilton squared off against Yates and Lansing at the New York Ratification Convention. Given this deep-seated political rivalry between Hamilton, Yates and Lansing, any new insights into their personal, professional, and legal interactions are potentially significant.

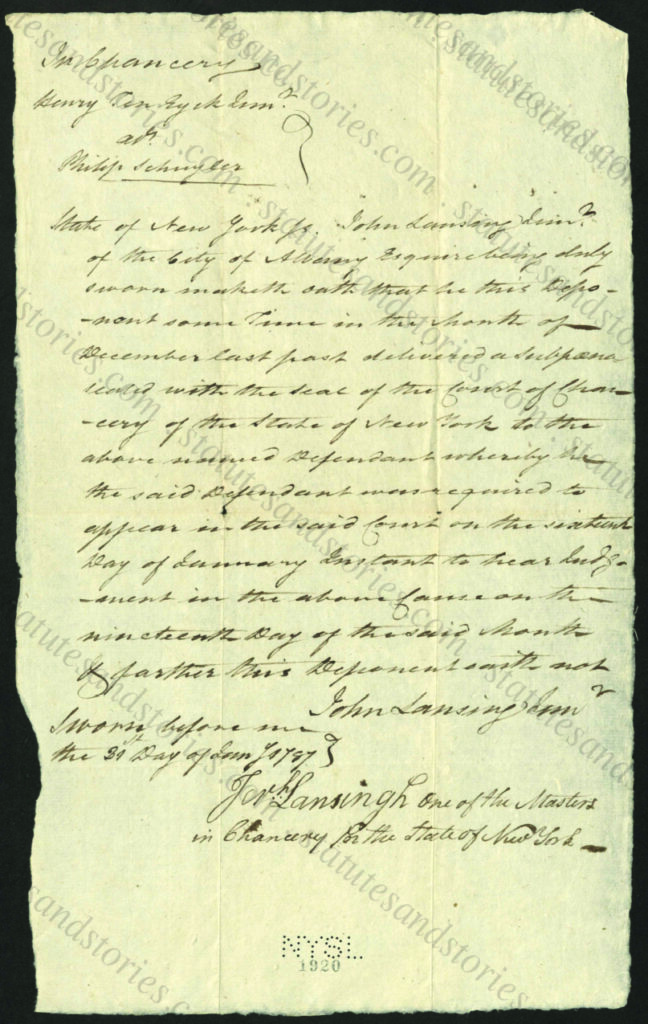

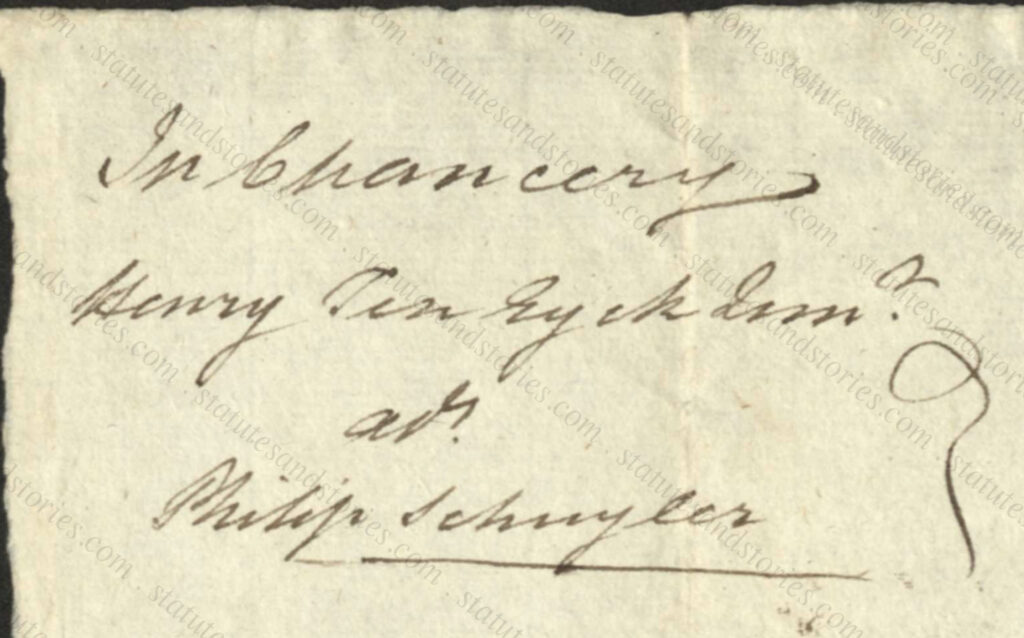

Lansing Affidavit in Ten Eyck v. Schuyler

John Lansing’s affidavit pictured above is puzzling. The “case style” at the top left corner of the affidavit indicates that it was prepared for filing in the New York Chancery Court. The “jurat” at the bottom of the page indicates that it was executed on January 31, 1787. In the affidavit, Lansing swears under oath that during the preceding month of December he “delivered a subpoena” containing the seal of the Court of Chancery of the State of New York to the defendant, Philip Schuyler.

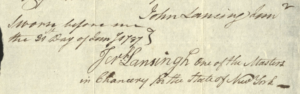

The affidavit explains that “said Defendant [Philip Schuyler] was required to appear in the said Court” on the 16th day of January “to hear judgment in the above cause” on January 19. After Lansing took his oath, the affidavit was signed by “Jerh Lansingh” as “one of the masters in Chancery for the State of New York.” While it is easy to confuse the names Lansing and Lansingh, it is safe to assume that Jeremiah Lansingh was serving as a notary, in contrast to attorney John Lansing who prepared and swore to the affidavit.

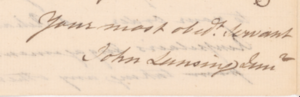

Pictured below is John Lansing’s signature on another letter which can be compared to the signature by “Jerh Lansingh” on the affidavit. Based on a review of the handwriting, it is clear that John Lansing wrote the affidavit. After Lansing took his oath, the affidavit was signed by Jeremiah Lansing, “one of the Masters in Chancery for the State of New York,” which is an antiquated name for a clerk who also serves as a notary public.

On the surface, one might assume that John Lansing was representing the plaintiff in the Ten Eyck v. Schuyler case. Why else would a lawyer deliver a subpoena to their own client? Today, for example, a modern lawyer might imagine preparing such an affidavit to hold a recalcitrant party in contempt of court. Given the adversarial political relationship between Hamilton and Lansing it is only natural to make this reflexive assumption. Yet, it is not clear from the document what precise role Lansing was playing in the case. One could speculate, for example, that the affidavit was filed on January 31 to obtain attorneys fees or court costs resulting from the January 16-19 hearing?

Unfortunately, the affidavit was a “single accession” added to the John Lansing papers in 1920. The affidavit has the markings of the New York State Library from 1920. After consulting with state archivists in Albany, we have not been able to find any other records in the Ten Eyck v. Schuyler case.

But all is not lost. Using correspondence culled from archives across the country, it is nonetheless possible to reconstruct some of the history of the case. In particular, correspondence between Alexander Hamilton, Philip Schuyler and John Lansing helps illuminate the relationships between the lawyers and parties in the Ten Eyck v. Schuyler case. As described below, this easily overlooked correspondence suggests that Hamilton and Lansing were working together in the case to represent Philip Schuyler. If so, Lansing and Hamilton were not adversaries, but rather allies in this intriguing case.

Hamilton’s 20 November 1786 letter to Schuyler about the Ten Eyck case

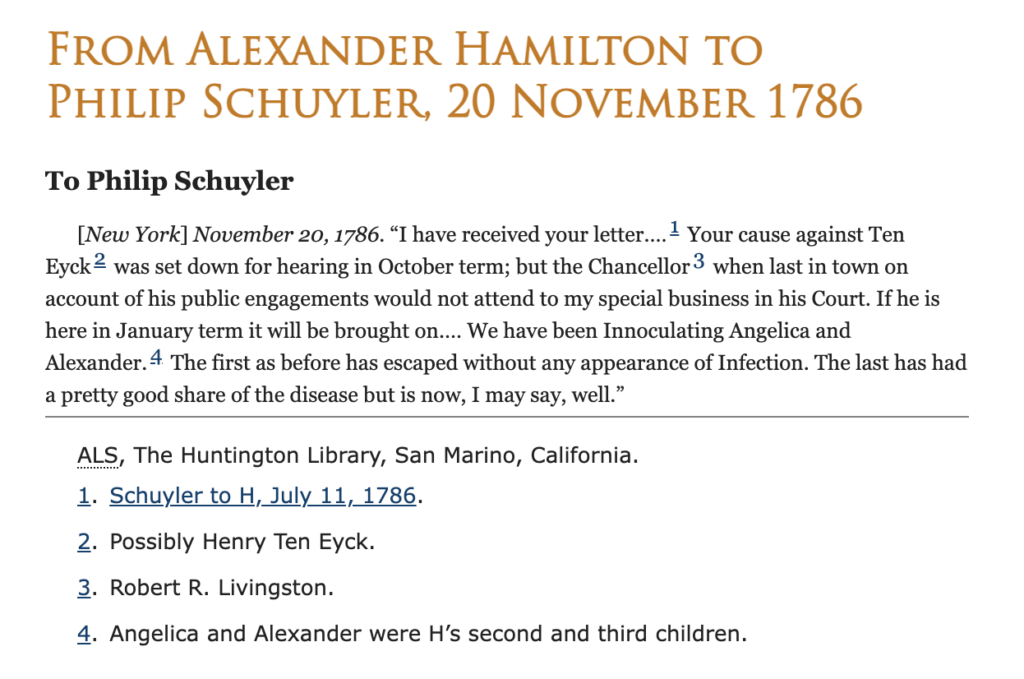

The first clue about the origin of Ten Eyck case appears in a 20 November 1786 letter from Alexander Hamilton to Philip Schuyler. Excerpts from the letter are included in the Hamilton Papers published by Columbia University Professor Harold Syrett. Over the span of three decades, Professor Syrett compiled Hamilton’s papers, which were printed in 27 volumes. While Syrett’s seminal work was pioneering in its day, Syrett made editorial decisions and omitted what he likely considered to be immaterial text from the published volumes of the Hamilton Papers.

Pictured below is the excerpted letter published by Syrett in 1961, which is available on the Founders Online website. Syrett did not see fit to reproduce the entire text of Hamilton’s three-page letter. Syrett noted, however, that the “autographed letter signed” (ALS) is housed at the Huntington Library in San Marino, California.

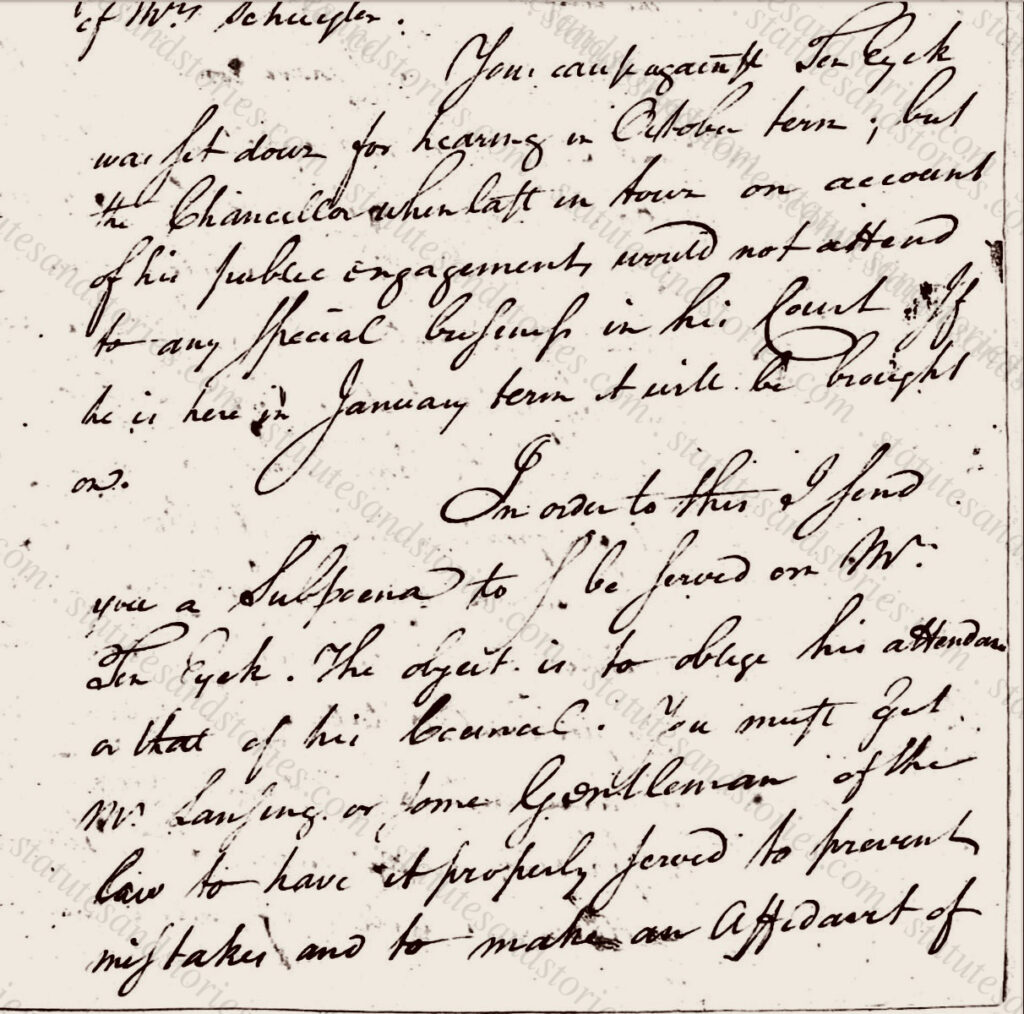

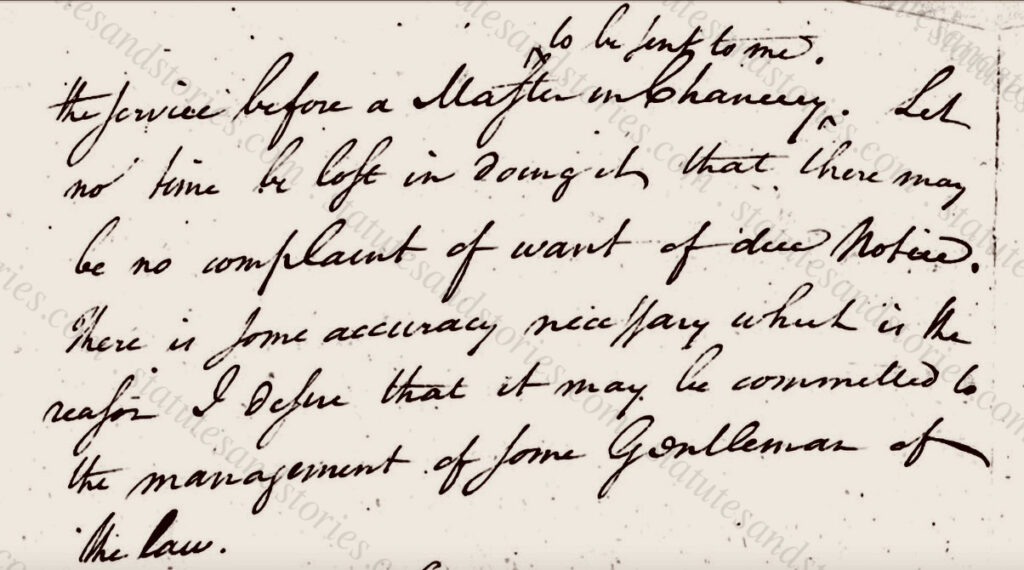

Sixty years later, Hamilton’s letter to Schuyler still resides at the Huntington Library. The staff at the Huntington was kind enough to provide the full text of the 20 November 1786 manuscript. A PDF is available from Statutesandstories.com upon request by fellow researchers. It is immediately evident that Syrett’s published excerpt omitted two relevant paragraphs about the Ten Eyck case. These paragraphs are reproduced for the first time online and are pictured below:

Your cause against Ten Eyck was set down for hearing in October term; but the Chancellor when last in town on account of his public engagements would not attend to my special business in his Court. If he is here in January term it will be brought on.

In order to this I send you a subpoena to be served on Mr. Ten Eyck. The object is to oblige his attendance and that of his Council. You might get Mr. Lansing or some Gentleman of the law to have it properly served to prevent mistakes and to make an affidavit of the service before a Master in Chancery to be sent to me. Let no time be lost in [ ] that there may be no complaint of want of due notice. There is some accuracy necessary which is the reason I desire that it may be committed to the management of some Gentleman of the law.

The following observations can be deduced from this omitted text:

- Hamilton was representing his father-in-law in the Ten Eyck v. Schuyler case;

- Hamilton prepared a subpoena to be served on Henry Ten Eyck;

- Hamilton recommended that Philip Schuyler secure the services of “Mr. Lansing or some Gentleman of the law to have it properly served to prevent mistakes and to make an affidavit of the service before a Master in Chancery”;

- Because Hamilton was located in New York City it made sense for him to work with “local counsel” based out of Albany, where Schuyler and Ten Eyck lived;

- Hamilton would still oversee the case from New York City, but wanted a local practitioner to properly serve the subpoena “and make an affidavit of the service before a Master in Chancery.”

- Hamilton trusted John Lansing, a prominent Albany lawyer (and Mayor of Albany) with this task.

- Hamilton was willing to recommend Lansing to Schuyler, despite their political differences.

Despite diligent efforts, StatutesandStories.com has not been able to locate any more files from the Ten Eyck v. Schuyler case. Yet, it is clear that Hamilton prepared a subpoena to be served on Ten Eyck. Hamilton trusted Lansing with this assignment, despite their political differences.

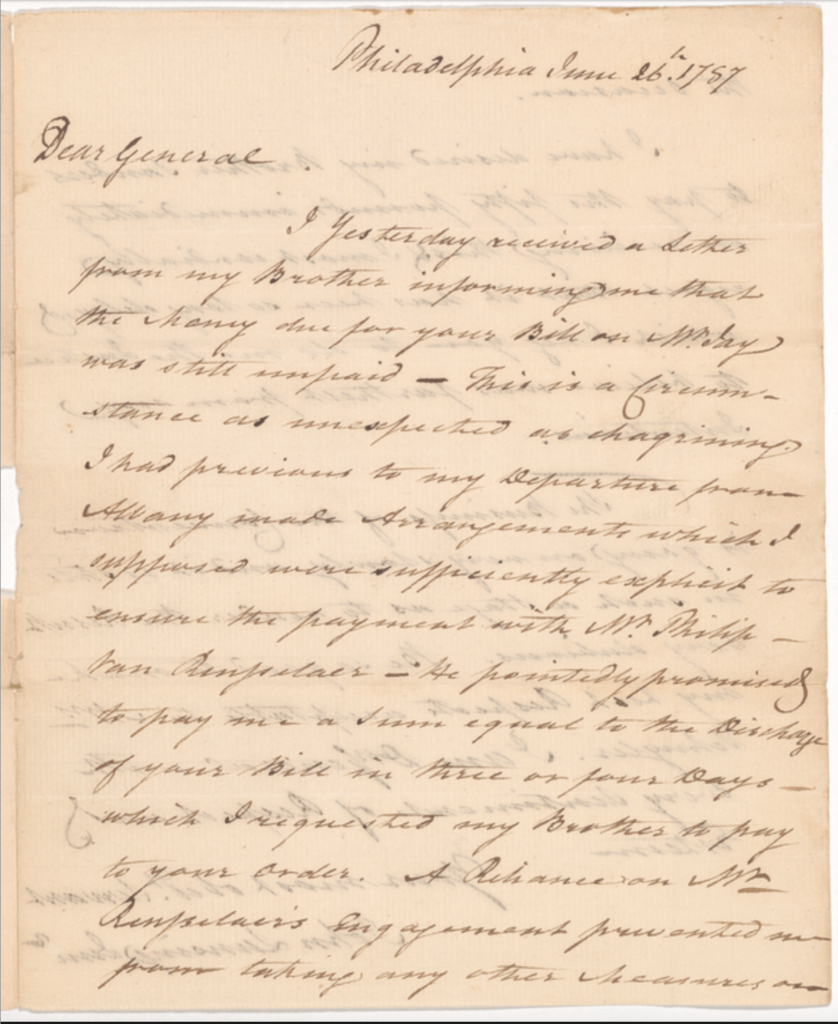

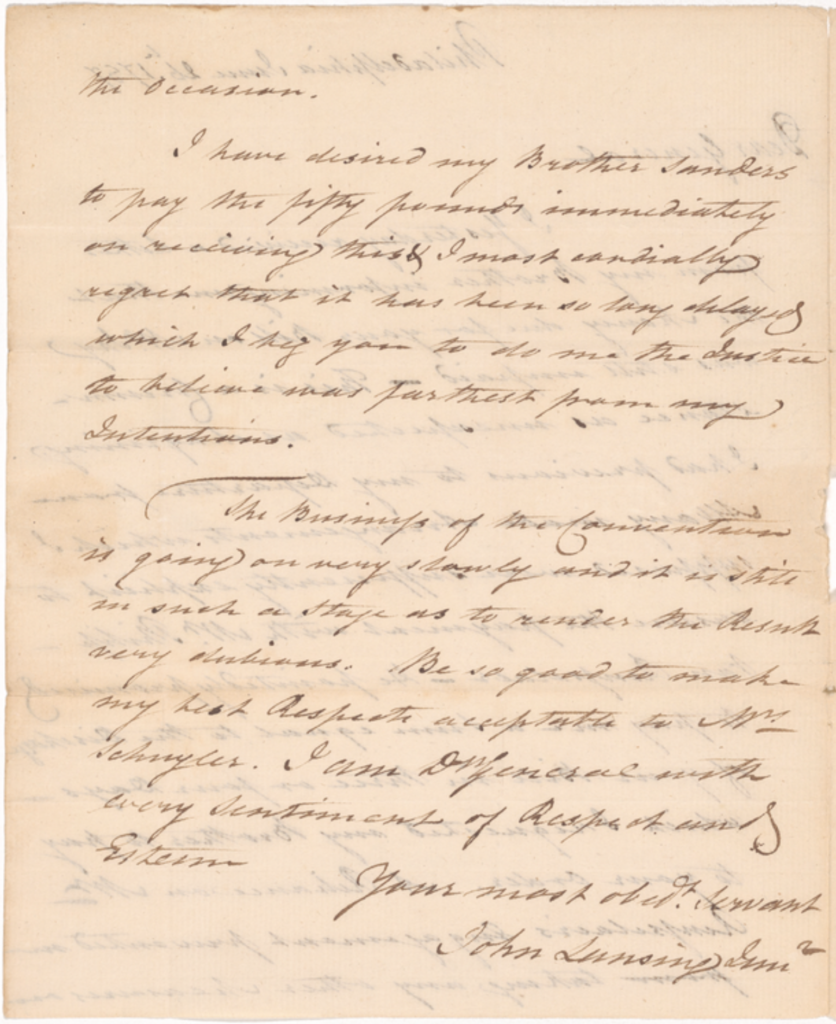

Lansing’s 26 June 1787 letter to Schuyler

Eight months later, during the Constitutional Convention, John Lansing wrote to Philip Schuyler. In a letter dated 26 June 1787, Lansing provides an update on legal matters that he was handling for his client, Philip Schuyler. As discussed below, there is no question that Schuyler was being represented by John Lansing in 1787. While it cannot yet be verified that Lansing was representing Schuyler in the Ten Eyck case, this is certainly a real possibility. Moreover, it is unlikely that Lansing would have been representing Schuyler in other cases, while simultaneously suing Schuyler in the Ten Eyck case.

A brief excerpt from John Lansing’s June 26 letter to Schuyler was published by James Hutson in 1987. Because Hutson was focused on records relating to the Constitutional Convention, Hutson only published the following sentence from the June 26 letter:

The business of the Convention is going on very slowly and it is still in such a stage as to render the result very dubious.

Thankfully, the New York Public Library has been digitizing its manuscripts. A full copy of Lansing’s June 26th letter is readily available and is copied below. It is noteworthy that Lansing was working with Schuyler to collect money owed from Mr. Jay. It is unclear if this was John Jay. Lansing writes that this circumstance was “as chagrinning as unexpected.” Prior to his departure for the Constitutional Convention, Lansing reports to Schuyler that he had made arrangements which he believed were “sufficiently explicit to ensure the payments with Mr. Philip Van Rensselaer.” While the specific matters discussed in the June 26 letter are beyond the scope of this article, it is clear that Lansing was working closely with Schuyler on legal/business matters.

It is noteworthy that at the same time that Lansing was working for Schuyler in June of 1787, Lansing and Schuyler/Hamilton were political rivals. Other relevant correspondence between Schuyler and Lansing includes a letter dated February 20, 1787 held by the New York Historical Society, which will be discussed in a pending blog post. While Lansing and Robert Yates were loyal lieutenants of Governor George Clinton, Hamilton and Schuyler were anti-Clintonians and would become leaders of the emerging Federalist party.

As suggested in the June 26th letter, John Lansing and Robert Yates would soon depart the Convention (on July 10). Hamilton left for New York on June 30. Hamilton would return in August and September. Yet, Hamilton would be the only delegate from New York to sign the Constitution on September 17.

The Investigation Continues

Alexander Hamilton was not known for shying away from a political battle. Yet, recent discoveries shed new light on an undercurrent of civility between Hamilton/Schuyler and their political rivals Yates/Lansing. A subsequent post (pending) will evaluate these relationships. For example, during the Revolutionary War, John Lansing served as General Schuyler’s military secretary. Hamilton served in a similar capacity as George Washington’s aide-de-camp. These bonds would prove to be enduring. It is suggested that there are lessons to be learned from the ability of the founding fathers (and mothers) to compartmentalize their political differences and compromise in furtherance of national objectives.

Sources and Further Reading

The Democratic Republicans of New York: The Origins, 1763-1797 (Alfred Fabian Young, 1967)

George Clinton: Yeoman Politician of the New Republic (Kaminski, 1993)

Supplement to Max Farrand’s The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787 (James H. Hutson, 1987)

Philip Schuyler papers (New York Public Library)

The Law Practice of Alexander Hamilton (Julius Goebel, 1964)