“Yates Returns” – Part V

Legal notices confirm Judge Robert Yates’ schedule in September of 1787

For over two hundred and thirty years historians were unaware of important behind-the-scenes details of the last days of the Constitutional Convention. New York delegates Robert Yates and John Lansing left the Convention on July 10, 1787. Following their departure from Philadelphia, it was universally assumed that they were “never to return again.”

Judge Robert Yates’ aborted effort to return to the Convention was discovered in late 2021. This post, Yates Returns Part V, provides additional evidence of the “Yates Returns” timeline, based on court records and published legal notices from the late summer and early fall of 1787.

Until last year’s discovery, first revealed here, and updated here, historians had no reason to doubt the “conventional” narrative. As described by Maryland Anti-Federalist delegate Luther Martin, “[t]he Honourable Mr. Yates and Mr. Lansing of New-York left us – They had uniformly opposed the system, and I believe, despairing of getting a proper one brought forward, or of rendering any real service, they returned no more.…” (emphasis added).

In their December 1787 report to New York Governor George Clinton, Yates and Lansing themselves acknowledged that, “We were not present at the completion….but before we left the convention, its principles were so well established as to convince us, that no alteration was to be expected….our further attendance would be fruitless and unavailing, rendered us less solicitous to return.”

Following the Yates Returns discovery in November of 2021, Statutesandstories.com has been carefully examining overlooked archival records that might shed light on Robert Yates’ schedule in August and September of 1787. This post provides an update on the ongoing process of reviewing court records and files.

Background about the New York Supreme Court of Judicature

Almost by definition, courts generate paperwork. The paper trail created by Judge Yates is discussed below, following a discussion of the New York Supreme Court of Judicature. In 1787 Robert Yates was a judge on New York’s Supreme Court of Judicature. He was initially appointed to the court in 1777.

By way of background, today’s New York Supreme Court (formerly the Supreme Cort of Judicature) was established in 1691, making it one of the oldest courts of general jurisdiction in the United States. Unlike other states, New York’s Supreme Court was and remains a lower level, trial level court.

Pursuant to legislation adopted by the New York Assembly, the Supreme Court of Judicature held jurisdiction over both criminal and civil cases. It was also empowered to hear appeals from inferior local courts. The Court’s “bench” consisted of a single Chief Justice along with two Associate Justices in New York City and Albany. Dating back to colonial times, appeals were taken to the royal governor and his council. In theory, appeals could subsequently be raised to the Privy Council in London.

When the Supreme Court of Judicature was established in 1691, it replaced the Court of Assize established in 1667. The Act of 1691 provided:

[T]he Supreme Court is hereby fully empowered and authorized to have cognizance of all pleas, civil, criminal and mixed, so fully and amply to all intents and purposes whatsoever, as the courts of Kings Bench, Common Pleas and Exchequer, within their “Majesties” Kingdom of England have or ought to have; in and to which Supreme Court all and every person and persons whatsoever shall or may, if they shall so see meet, commence or remove any action or suit, the deed or damage in any such action or suit being upwards of twenty pounds, and not otherwise, or shall or may by warrant, writ of error or certiorari, remove out of any of the respective courts of Mayor and Aldermen, Sessions and Common Pleas, judgment, information or indictment there had or depending, and may correct errors in judgment, or reverse the same, if by just cause, provided always that the judgment removed shall be upwards of the value of twenty pounds.

In addition to hearing cases, the Supreme Court of Judicature also had appellate jurisdiction over lower, local courts and officials, including justices of the peace. For example, Laws of 1787, Chap. 72, provided for issuance of writs of habeas corpus to remove civil causes from inferior courts into the Supreme Court of Judicature. Of course, a writ of habeas corpus was also used by the Supreme Court of Judicature to command a judge, sheriff, or jail to deliver an individual into the custody of the Court, and to state the legal authority for the detention.

New York’s first constitution was adopted in 1777. Article 35 declared that:

[S]uch parts of the common law of England and of the statute law of England and Great Britain, and of the acts of the legislature of the colony of New York, as together did form the law of the said colony . . . shall be and continue the law of this State subject to such alterations and provisions, as the Legislature of this State, shall from time to time, make concerning the same.

Article 35 retained the colonial court structure inherited from England. Until substantially reorganized in 1847, the Supreme Court of Judicature was New York’s highest court with original jurisdiction.

The first Chief Justice of New York’s Supreme Court of Judicature was John Jay. In 1790, Robert Yates was appointed Chief Justice by Governor George Clinton, becoming only the third Chief Justice post-independence. In 1787, John Lansing was the Mayor of Albany and a practicing lawyer. Lansing would subsequently become the fourth Chief Justice in 1798, after Yates’ retirement.

Until 1820, the Supreme Court of Judicature held its regular sessions in only two locations, New York City and Albany. In 1785, it was decided that the Court should hold two terms each year in Albany. While individual judges would travel “the circuit” on a regular basis to surrounding counties, Judge Yates was based out of his home in Albany. When traveling on circuit he would sit with local judges on the Court of Oyer and Terminer.

Because Albany was one of the court’s only two fixed locations in 1787, this post grows out of continuing efforts to drill down into Albany court records. In particular, this post focuses on Judge Yates’ calendar in the late summer and early fall of 1787, after he departed the Constitutional Convention on 10 July 1787 with John Lansing. The Yates Returns’ timeline is discussed in Part IV.

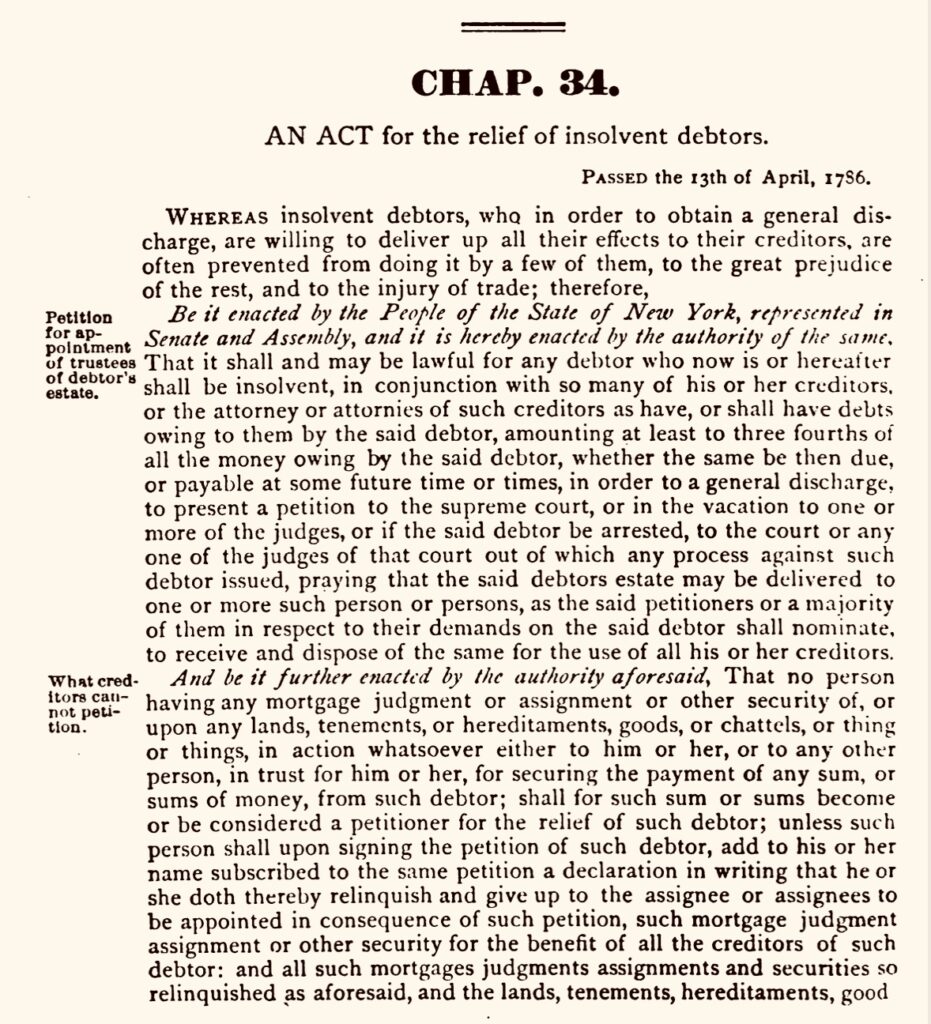

New York’s Act for Relief of Insolvent Debtors

On April 13, 1786 New York adopted an important, early bankruptcy law, the “Act for Relief of Insolvent Debtors” (New York Laws of 1786, Ninth Session, Chapter 24). At the time, the nation was facing a severe recession. Shays’ Rebellion in Massachusetts is a well-known example of the economic conditions and resulting dislocations which preceded the Constitutional Convention in May of 1787. Not surprisingly, the new bankruptcy law generated a large volume of court filings. The Act can be found on page 242 of the 1886 republished edition of the Laws of the State of New York, Vol II.

New York’s Act for Relief of Insolvent Debtors set forth a detailed procedure to allow a debtor to be discharged. The alternative was a horrific and often indeterminate stay in debtor’s prison.

Copied above is the title and first page of the six-page Act. Importantly, the sixth paragraph of the Act required that “notice shall be given by the petitioners to all the creditors of such debtor, by advertising the same in two or more of the public news papers, to show cause if any they have, by such a day as shall be appointed by the court….why an assignment of said debtors estate should not be made, and the debtor discharged.”

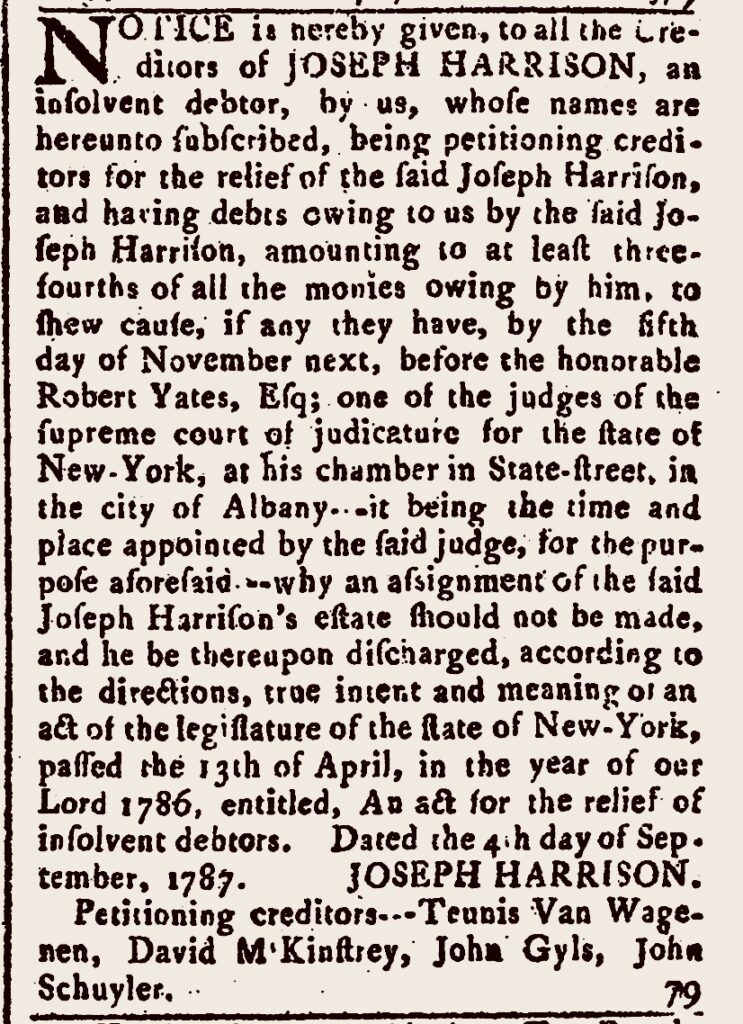

Copied below is a sample legal notice to the creditors of Joseph Harrison, based on an Order signed by Judge Yates on 4 September 1787. The Harrison notice was published in the Albany Gazette on October 15, 1787.

Under the Act, each new case filing would ordinarily generate the following activity and court records:

- Petition by the insolvent debtor requesting that the insolvent’s property be assigned to a trustee (assignee) for sale;

- Legal notice/advertisement of the new case filing, published in two or more local newspapers, identifying the debtor and the date of the first court hearing;

- Affidavit of the petitioning creditors setting forth the debt owed;

- Account of debts of the insolvent debtor, with names of debtors and amounts owed;

- Account of any real estate, along with an inventory of the personal assets of the insolvent debtor;

- Court Order to advertise the impending sale of real property, notifying other creditors to show cause why the sale should not be made;

- Affidavit of publication;

- Order for assignment of the insolvent’s property to trustees for sale for benefit of the creditors;

- Certificate of assignment by the trustees (assignees), confirming delivery of the property; and

- Affidavit/report of assignment, discharging the debtor from liability for debts incurred prior to the date of the petition.

Yates Returns Timeline:

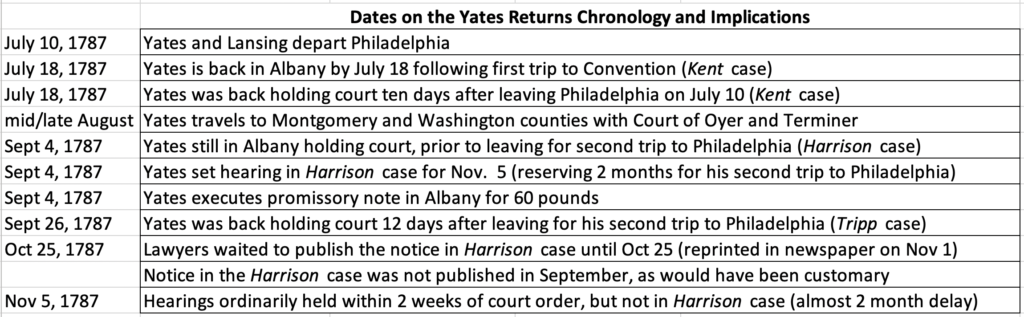

The Harrison legal notice is powerful evidence confirming the timeline for Judge Robert Yates’ return trip to the Convention. The information discussed below in the Harrison, Kent and Tripp cases aligns perfectly with the fact that Judge Yates left Albany in mid-September to return to the Convention, but arrived too late.

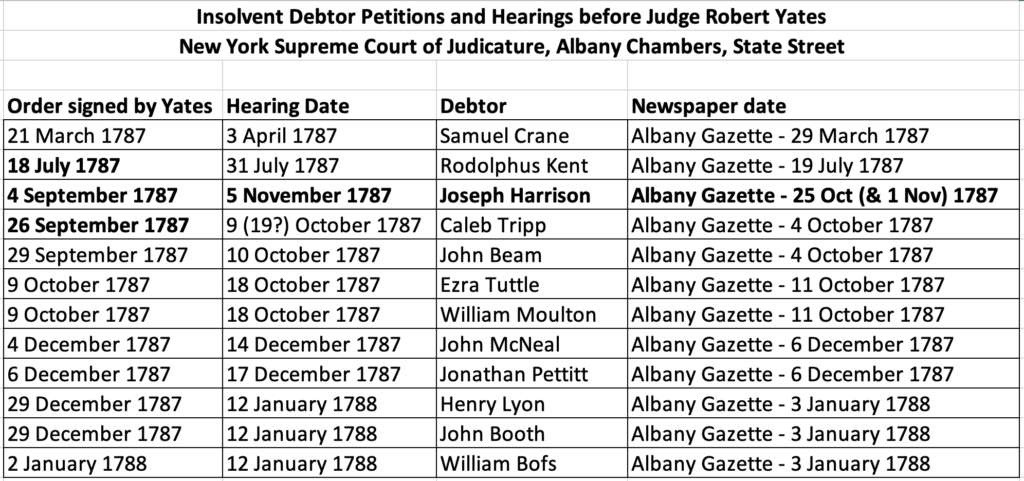

The following chart gathers together information from a dozen insolvency cases heard by Judge Yates in 1787 and early 1788. Importantly, the chart establishes that a hearing date would regularly be set approximately ten days to two weeks following the entry of the initial order in an insolvency case under the 1786 Act.

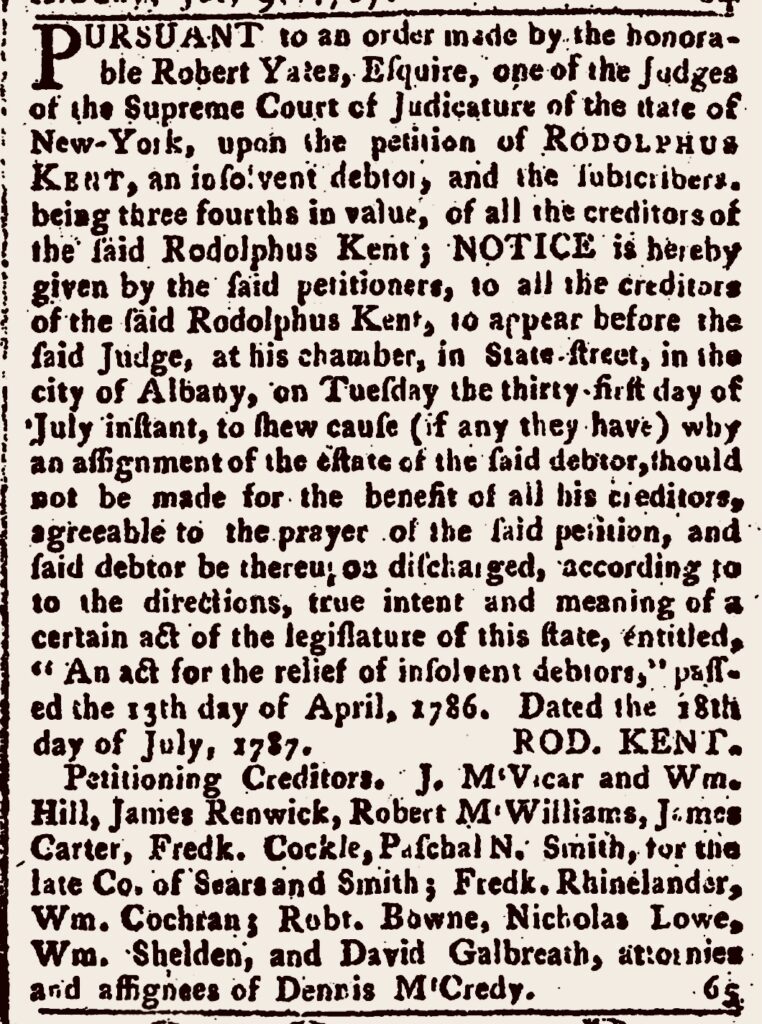

For example, in the Crane case, Judge Yates signed the initial order on March 21, setting a hearing date on April 3. Similarly, in the Kent case Judge Yates signed the initial order on July 18, setting a hearing on July 31.

The Kent and Harrison cases are significant for several reasons. First, Judge Yates’ entry of an order in the Kent case on July 18 confirms that he was back in Albany, hearing cases ten days after leaving the Constitutional Convention on July 10. Thus, the Kent case can be considered an important bookend in the “Yates Returns” timeline.

The Harrison case establishes that Judge Yates was hearing cases on September 4, prior to his aborted second trip to Philadelphia. Interestingly, Judge Yates set the hearing date in the Harrison case for November 5, two months after the initial September 4 order. While a two-month waiting period to hold a hearing is not unusual for modern lawyers, the above chart demonstrates that this delay in the Harrison case was unusual.

Two hundred and thirty years later, we now know why the hearing in the Harrison case was delayed. Judge Yates expected that he would be out of town in Philadelphia starting in mid-September.

As discussed above, ordinarily the hearing in an insolvency case was held ten to fourteen days after the entry of the initial order. Yet, on September 4 Judge Yates set a hearing date in the Harrison case for November 5, two months – not two weeks – from the date of the initial order. Why?

Based on other evidence summarized in Part I, Judge Yates attempted to travel to Philadelphia in mid-September. He submitted a bill for six days of travel to New York City, where he learned that the Philadelphia Convention had “risen.” After learning that he was too late, Yates then turned around and spent six days returning to Albany. According to records of the New York State Auditor discovered in 2021, Judge Yates requested and was paid £ 19 and 4 shillings from the State of New York. This sum represented a total of twelve days of travel, at 32 shilling per day, from Albany to New York City (and back).

The Kent order establishes that Judge Yates was back in chambers, hearing cases by July 18. The Harrison order provides strong evidence that Judge Yates knew that he would be out of town in mid-September. Otherwise, the Harrison hearing should have been set for mid-September, not early November. While we cannot read Judge Yates’ mind, this conclusion is also supported by the fact that Judge Yates borrowed £60 on September 4, likely because he knew that he needed hard currency for his pending return trip to Philadelphia. The promissory note floated by Judge Yates on September 4 is discussed in Yates Returns Part IV.

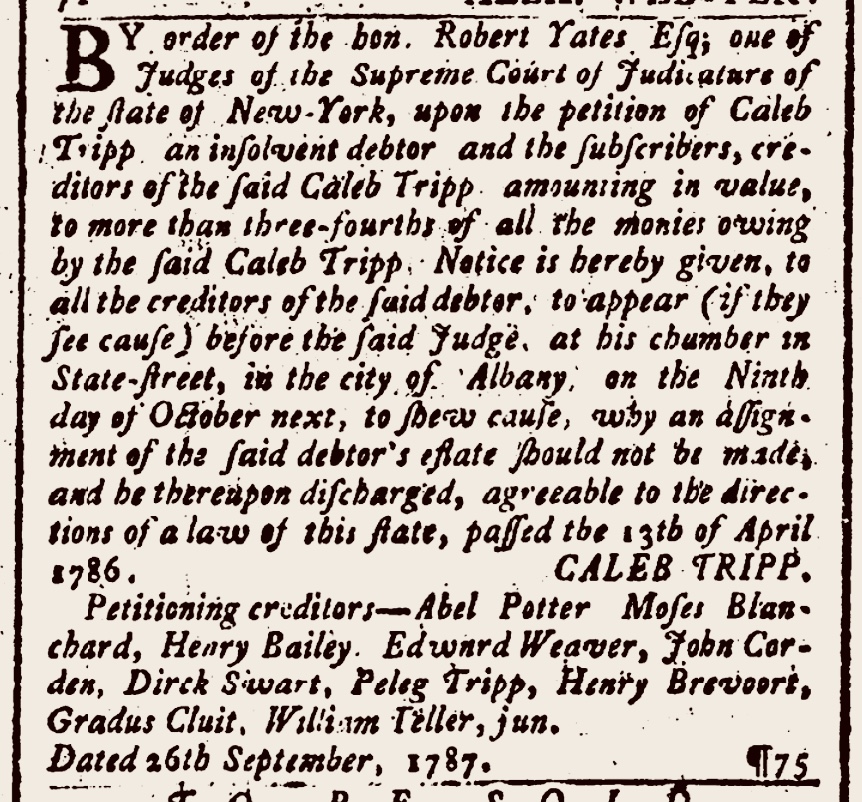

The ironically named Tripp case, provides the final bookend on the “Yates Returns” timeline. On September 26, Judge Yates was back in Albany where he entered the initial order in the Tripp case.

According to the “Yates Return” timeline it is reasonable to surmise that Judge Yates departed Albany for Philadelphia on or around September 14. He arrived in New York City six days after leaving Albany. According to Judge Yates, he learned that the Convention had risen one day “after my arrival” in New York City. The Convention adjourned on September 17. Thus, Judge Yates likely arrived in New York City on or before September 20, when news of the signing of the Constitution first became public in New York City.

The timeline discussed in Part IV, with Judge Yates leaving New York City for Albany on or before September 20, aligns perfectly with the September 26 order in the Tripp case. As per usual practice, Judge Yates set the hearing in the Tripp case for October 9 (or 19). It is noteworthy that the October hearing date in the Tripp case was well before the November 5th hearing date in the Harrison case. Again, we know why. By September 26 Judge Yates had returned from New York City, with knowledge that the Convention had adjourned. When he set the October hearing in the Tripp case, Judge Yates knew that there would not be any more trips to Philadelphia!

This expanded timeline, using the Kent, Harrison and Tripp insolvency cases is illustrated in the following chart:

The published court notices in the Kent and Tripp cases are copied below. Each was printed in the Albany Gazette, pursuant to the sixth paragraph of New York’s Act for Relief of Insolvent Debtors.

Notice in Kent case

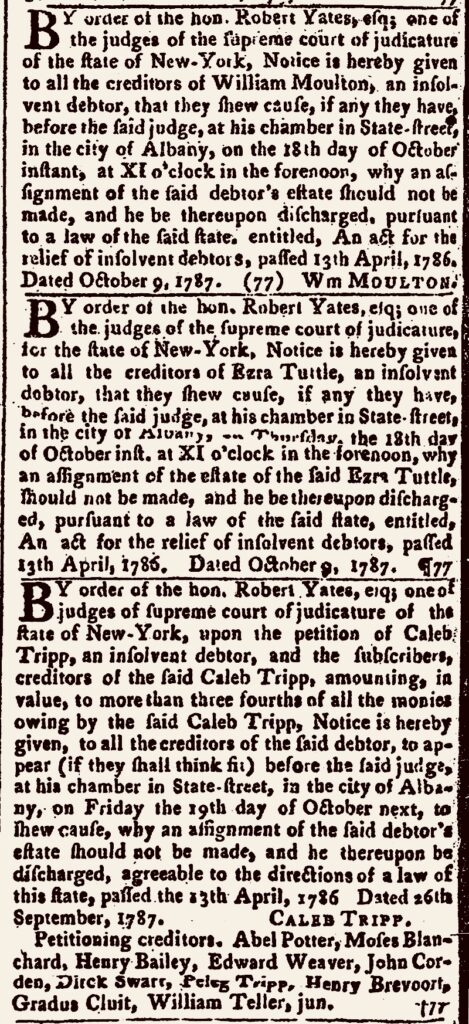

Notice in Tripp, Moulton, and Tuttle cases

The first notice in the Tripp case was published on October 4, indicating an order dated September 26th set the initial hearing for October 9th. The second notice in the Tripp case was published on October 11, indicating that the hearing date was set for October 19. It is unclear whether the October 9th date was a typo, or whether the date was changed by Judge Yates. Regardless of the October 9 (or October 19) date, the fact remains that Judge Yates was back in Albany on September 26th when he signed the initial order in the Tripp case.

Copied below is the first notice published in the Tripp case.

Copied below is the second notice in the Tripp case, along with notices in the Moulton and Tuttle cases. Other notices described in the chart above are available upon request by any researcher/fellow traveler.

This post will be updated with images from the New York State Archives, Albany Hall of Records, and any other court records that become available. Scholars and other researchers are invited to assist with this continuing investigation.

Additional reading and sources:

A History of the Bench and Bar of Albany County, W. Dennis Duggan (Historical Society of the New York Courts, 2021)