Late-breaking new discoveries in Albany involving the Constitutional Convention

The long road back to Philadelphia and the confrontation that never was

By Professor John Kaminski, Adam Levinson, Esq. & Sergio Villavicencio

In an iconic scene etched into America’s national identity, thirty-eight delegates lined up to sign the Constitution on September 17, 1787. Yet, a new discovery in the New York State Archives suggests that events could have gone very differently that day. This article provides an overview of groundbreaking research which could reshape our understanding of what was occurring behind the scenes during a seminal moment in American history. The discussion continues in Part II which asks a series of questions prompted by the unexpected discovery that New York delegate Robert Yates attempted to return to the Constitutional Convention in September of 1787.

The message of unanimity when the Constitution was unveiled

In the debate for ratification of the Constitution, the Federalist supporters of the Constitution united behind a simple, easy to understand and otherwise compelling message: During the summer of 1787 the nation’s brightest minds and heroes of the American Revolution met in Philadelphia where they unanimously agreed that the proposed Constitution was necessary to secure the fruits of the struggle for independence. While the Constitution was not perfect, it was “the result of a spirit of amity” and “mutual deference and concession” which prevailed in Philadelphia, in the same building where the Declaration of Independence had been adopted in 1776.

This message of unanimity was communicated in the cover letter which introduced the Constitution to the world. Washington’s September 17 letter accompanied the Constitution on its trip from the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia to Congress in New York City. Signed by George Washington as President of the Convention, the transmittal letter to Congress indicated that the Constitution was approved “by unanimous Order of the Convention.” Washington’s cover letter would be printed with the Constitution in every state, in approximately 100 newspapers as well as in broadsides and pamphlets.

According to James Madison’s notes, Alexander Hamilton emphasized the importance of unanimity on the last day of the Convention, September 17. “Mr. Hamilton expressed his anxiety that every member should sign. A few characters of consequence, by opposing or even refusing to sign the Constitution might do infinite mischief by kindling the latent sparks which lurk under an enthusiasm in favor of the Conventoin which may soon subside.” Hamilton indicated that “No man’s ideas were more remote from the plan than his own were known to be; but is it possible to deliberate between anarchy and Convulsion on one side, and the chance of good to be expected from the plan on the other.”

In Benjamin Franklin’s famous speech on September 17, he confessed that “there are several parts of this constitution which I do not at present approve, but . . . Sir, I agree to this Constitution with all its faults if they are such; because I think a general Government necessary for us . . . I doubt too whether any other Convention we can obtain may be able to make a better Constitution.” At the end of his speech, which was read aloud by James Wilson, Franklin moved that the Constitution be signed by the members with the following format:

Done in Convention, by the unanimous consent of the States present the 17th of September – In Witness whereof we have hereunto subscribed our names.

As recounted by Madison, this “ambiguous form” was drawn up by Gouverneur Morris “in order to gain the dissenting members, and put into the hands of Doctor Franklin that it might have the better chance of success.” In other words, through the use of semantic slight of hand, the signers would not all need to personally agree to the Constitution. Rather, they would only affirm how the state delegations had voted.

Indeed, this artifice helped persuade William Blount of North Carolina to play along and sign the Constitution. Blount admitted that “he had declared that he would not sign, so as to pledge himself in support of the plan, but he was relieved by the form proposed and would without committing himself attest the fact that the plan was the unanimous act of the States in Convention.”

Eleven days later, on September 28, Congress “unanimously” agreed to send the Constitution to the states for ratification. Not reported in newpapers, however, was the fact that several Anti-Federalist members of Congress had strongly disagreed. In their mind, the Convention had committed “constitutional impropriety” by exceeding their instructions and attempting to replace rather than revise the Articles of Confederation. Nevertheless, Congress reached a compromise that would be hidden from the American public and stricken from the Congressional record. Congress resolved “unanimously” merely to send the Constitution to the states, but did not express any “approbation” or official opinion about the merits of the proposed Constitution. The ultimate decision would be reached by the “people,” at the state ratification conventions.

The confrontation that never happened

Among 826 volumes of New York financial records, journals and ledgers newly uncovered evidence reveals an aborted effort to prevent this narrative of “unanimity.” While the story of the events of September 1787 summarized above has been exhaustively studied by generations of historians, a long overlooked financial record was buried among 442.2 cubic feet of records in Albany. In fact, it is poetic that this record was discovered of all places – in New York – where the rest of the story begins.

Of the twelve states in attendance at the Convention on September 17, only one state lacked a functioning delegation. Eight delegates from Pennsylvania signed the Constitution; five signed from Delaware. By contrast, two of New York’s three delegates departed the Convention in mid-July, based on their fundamental disagreement with the direction that the Convention was taking. Thus, only one delegate from New York signed the Constitution on September 17. As indicated in George Washington’s diary that day:

Met in Convention, when the Constitution received the unanimous assent of 11 States and Colonel Hamilton’s from New York.

Hamilton had also departed from the Convention in late June. He briefly made an appearance in August. As the Convention was wrapping up its work, Hamilton returned in early September and joined the Convention’s final committee. Accordingly, as the sole delegate from New York in attendance on September 17, Hamilton signed the Constitution, even though as a lone delegate he lacked the authority to vote.

This did not stop Hamilton from signing in his own individual capacity. In fact, before the Constitution was signed, it was none other than Hamilton who wrote the names of the states at the bottom of the Constitution beside which the delegates signed their names. This scripted narrative might have turned out very differently, however, if either of New York’s two other delegates had known what Hamilton was planning.

Hamilton’s co-delegates from New York were purposely chosen months earlier because they were avowed opponents of the reforms that Hamilton had been proposing. When they were present in Philadelphia, they consistently outvoted Hamilton and opposed the Virginia Plan. If either of New York’s other delegates had been present on September 17, the delegation would have been divided and no New York delegate would have signed the Constitution. The critical unanimity would never have been achieved.

Follow the money

Until now historians have assumed that in mid September of 1787 New York delegates Robert Yates and John Lansing, Jr., were back in Albany plotting their opposition to ratification. It turns out, however, that Yates attempted to crash the party in Philadelphia and stop Hamilton from casting New York’s assent to the Constitution. While we don’t know exactly what Yates had in mind, it is clear that if he had arrived in Philadelphia before the signing, he would have attempted to prevent Hamilton from signing the Constitution on behalf of New York. Judge Yates may also have been able to peel off other reluctant delegates.

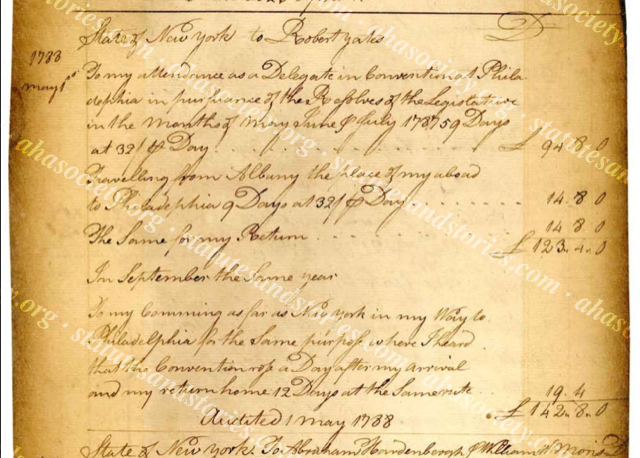

The newly discovered record pictured below is unmistakable. In September of 1787, Yates made a desperate, last minute effort to return to Philadelphia to offset Hamilton at the conclusion of the Convention. Fortunately for the Federalists, Yates was too late. According to the exciting new discovery, Yates made it from Albany to New York City, at which time he learned that the Convention had just adjourned. History could have been very different if Yates had a faster horse, but thankfully he was no Paul Revere.

This revelation was the result of tracking the reimbursement sought by Yates the year after the Convention, which was contemporaneously audited and documented by the New York Auditor in May of 1788. Future articles will examine a host of questions which are raised by this new discovery:

- How did Yates learn that Hamilton was back in Philadelphia?

- Who else knew?

- Did Yates attempt to communicate with his colleague John Lansing or Governor Clinton?

- What was Yates planning to do?

- What other records exist that might shed additional light on Yates’ activity in September of 1787?

The discussion continues in Part II.