Yates’ return trip to the Convention: Intriguing questions

Professor John Kaminski, Adam Levinson, Esq., Sergio Villavicencio

This week we reported our surprising discovery that New York delegate Robert Yates attempted to return to the Constitutional Convention in September of 1787. Click here for the late breaking report from Albany (Part 1). This previously unexpected event demonstrates that after 230 years, we may still have much to learn about the dramatic closing days of the Constitutional Convention.

This post is the continuation of our November 9 report that more was going on behind the scenes in the famously divided New York delegation than was previously known. Buried among 826 volumes (442.2 cubic feet) of ledgers/journals/payment registers in the New York State Archives is the overlooked documentation that Yates sought reimbursement for a total of twelve days “coming as far as New York [City]” on his way to Philadelphia, before he learned that the Convention had adjourned “a day after my arrival…”

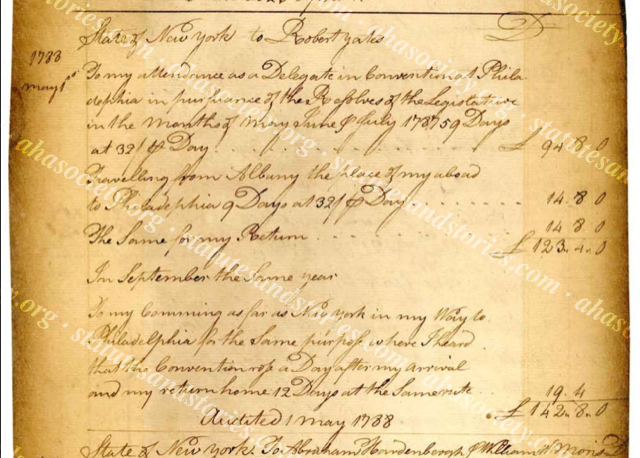

As pictured below, Yates explains that he traveled from “the place of his abode” in Albany “for the same purpose” as the fifty-nine days he was serving as a “delegate in Convention at Philadelphia…” Yates further explains that this work “in September the same year” was “in pursuance of the resolves of the Legislature” during the months of May, June and July, 1787.

Thus, at the very moment that the Constitution was leaving Philadelphia to travel north to New York City, Yates was traveling south from Albany. William Jackson, the Convention Secretary, departed Philadelphia with the Constitution on September 18th and arrived in New York on September 20. While we don’t know precisely what day Yates left Albany, he learned that the “Convention rose a day after my arrival” in New York City. Yates billed the state of New York £19 & 4 shilling for a total of “12 days,” presumably 6 days in each direction “at the same rate” of 32 shilling per day.

Admittedly, this new information about a seminal event in American history raises more questions than it answers. Accordingly, the purpose of this post is to invite scholars to join us as we attempt to re-examine a long-held narrative that we believe deserves closer scrutiny.

In particular, we suggest that a concerted effort be made to revisit archival records relating to Robert Yates, John Lansing and Governor George Clinton during the period of July through September of 1787. Unfortunately, no biography was ever written about Robert Yates. Moreover, Robert Yates’ papers were never compiled together as was the case for other framers including John Lansing, Jr. (whose papers are held in the New York Public Library and New York State Library). With that said, Professor John Kaminski’s 1993 biography of George Clinton provides a valuable launching pad, as does Stefan Bielinski’s 1975 biography of Abraham Yates, Jr., Robert’s older uncle. It is also fortunate that some of George Clinton’s records were preserved, prior to the 1911 fire in Albany.

What we know about the payments

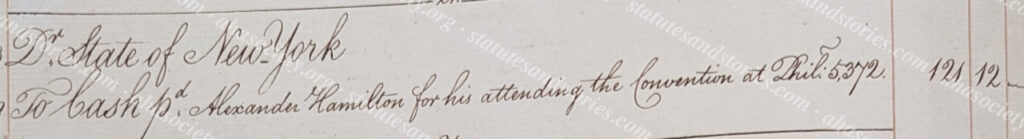

Earlier this year we answered a question left unaddressed by generations of Hamilton biographers. As acknowledged years ago by Broadus Mitchell’s two volume biography of Alexander Hamilton, “we do not know” whether Hamilton was paid to attend the Constitutional Convention. Now we do.

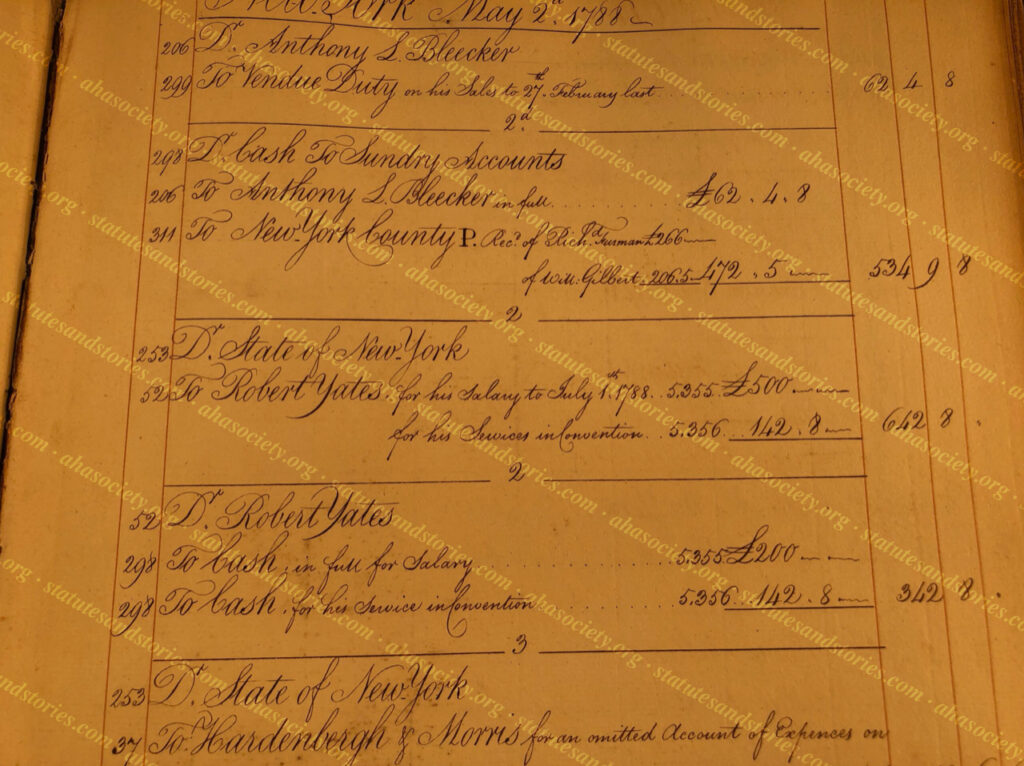

Virginia paid its delegates $6 per day; New Jersey delegates were paid $4 per day; Delaware paid its delegates 40 shilling per day; and Pennsylvania likely didn’t pay any expenses, having selected eight delegates who lived in Philadelphia. Click here for a link to volume 1 of Professor Vile’s Encyclopedia of the Constitutional Convention. We can now authoritatively answer that New York paid Hamilton, Yates and Lansing exactly 32 shilling per day.

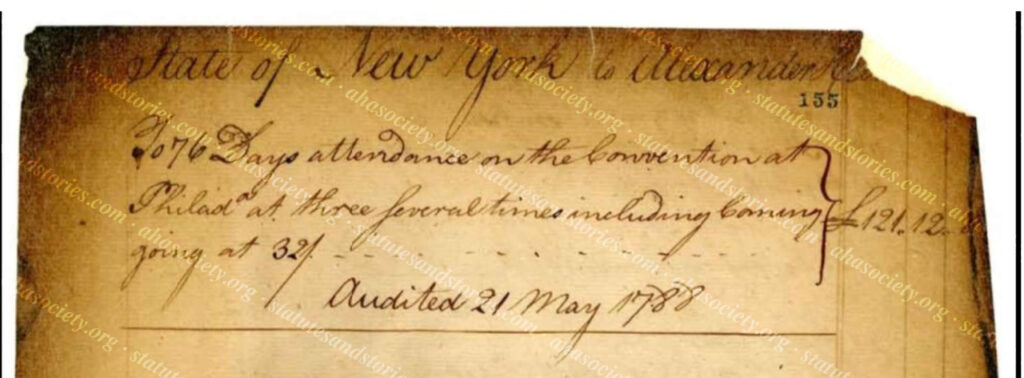

This new revelation about Yates’ aborted second trip helps explain why Yates was paid a total of £142 & 8 shilling, whereas Hamilton was only paid £121 & 12 shilling. Click here and here for a discussion of this summer’s discovery that Hamilton, Yates and Lansing were compensated in April and May of 1788 for their time in Philadelphia. Click here for a discussion of the significance of these discoveries. Note that the separate journal entries for Yates and the subsequent audit by the New York Auditor both confirm the same payment amounts, £142 & 8 shilling. Likewise the journal entry for Hamilton and the subsequent audit amounts correspond, £121 & 12 shilling.

The fire damaged audit records pictured above are easy to identify due to darkened edges. The fact that Hamilton’s name is missing from the top right corner above may help explain why the record was not previously identified as a payment to Hamilton.

Yates and Lansing’s role

We know that Robert Yates and John Lansing, Jr., left Philadelphia on or about July 10, during the sixth week of the Convention. Hamilton had departed approximately 10 days earlier on or about June 30th. Historians have assumed for the past two centuries that when Yates and Lansing left they had no intention of returning. Was this a valid assumption?

As one of the most populous states, New York would theoretically have been entitled to considerable influence at the Convention. When Yates and Lansing departed, they deprived New York of any role that it might have played in Philadelphia. By contrast, even though George Mason, Edmund Randolph, and Elbridge Gerry refused to sign the Constitution, they remained in Philadelphia as active members of the Convention through September 17.

Hamilton wrote to Yates and Lansing on or before August 20 offering to join them if they would accompany him back to Philadelphia. As described by Hamilton in an August 20 letter to Rufus King, his future committee member on the Committee on Style:

I have written to my colleagues informing them, that if either of them would come down I would accompany him to Philadelphia. So much for the sake of propriety and public opinion.

- Did Yates and Lansing understand Hamilton’s letter to mean that he would only go back to Philadelphia if one of them joined him?

- Did Hamilton purposely write his August letter to create this impression?

- Where is Hamilton’s letter to Yates and Lansing? Does a copy still exist?

- Did Hamilton intend to return to Philadelphia with or without his co-delegates.

- Did he prefer that they not join him, so he would be free to act, even if he couldn’t vote?

We know that Yates and Lansing were specifically selected by the New York Legislature to counteract Hamilton. As described by Henry Cabot Lodge over 100 years ago, Yates and Lansing were “uncompromising Clintonians and state-rights men, who could be relied upon to vote against any form of improved federal government.” According to Richard Beeman in Plain Honest Men: The Making of the American Constitution, Yates and Lansing were “staunch opponents of the efforts to strengthen the continental government” and had proven their mettle in the battle over the federal impost earlier in the year. Click here for a discussion of the defeat of the Impost of 1783.

Ron Chernow described Yates and Lansing as a “tightly knit pair” who were “vocal foes of efforts to endow Congress with independent taxing powers.” Yates and Lansing were related by marriage and both hailed from Albany. Lansing clerked as a teenager in Yates’ law firm. Ron Chernow observes that rather than leading a united delegation, “Hamilton was demoted to being a minority delegate from a dissenting state.” According to Chernow, the “chief catalyst for the convention” would be hamstrung by a hostile Governor and his anti-reform surrogates. Click here for a more detailed discussion of Governor George Clinton’s plan to sabotage Hamilton at the Constitutional Convention.

The instructions for the New York delegation were also intended to limit Hamilton’s autonomy. By contrast, Virginia broadly instructed its delegates to take such action “as may be necessary to render the Fœderal Constitution adequate to the Exigencies of the Union.” New York narrowly circumscribed its delegation using the limitations offered by Congress when it called on the states to send delegates to the Convention for “the sole and express purpose of revising the Articles of Confederation.” Interestingly, Senator Abraham Yates, Robert Yates’ uncle, had proposed using these instructions. Perhaps because he was aware of Hamilton’s nationalistic agenda, Abraham Yates had further proposed that New York’s instructions require delegates to abstain from voting for anything that would violate New York’s constitution.

What we dont know?

The fact that Yates and Lansing were charged with limiting Hamilton’s effectiveness on the three member New York delegation begs following the questions:

- How did Clinton react when he learned that Hamilton had signed the Constitution on behalf of New York?

- Did Clinton blame Yates and Lansing for leaving Philadelphia when he read that the Constitution had seemingly been approved by a unanimous vote of the states? Perhaps this may explain Robert Yates’ effort to return to Philadelphia, when he presumably learned that Hamilton was back in town.

Set forth below are a host of additional questions, which will be expanded over time if more information potentially comes to light.

- Why did Robert Yates return to Philadelphia? Presumably Yates learned of Hamilton’s arrival in Philadelphia in early September.

- Is it possible that Hamilton’s election to the Committee on Style on September 8 was the trigger for Yates to return from Albany?

- Is it reasonable to infer that Yates attempted to return to Philadelphia to check Hamilton and/or stop Hamilton from signing the Constitution?

- Did Yates try to contact Lansing? Or, did he know that Lansing was preoccupied with legal work in Washington County?

We know that Senator Abraham Yates, Jr., wrote to Jeremiah van Rensselaer on August 29 that he had learned in Congress that Rufus King believed that the Convention would conclude “by the first of September.” After having spoken to King, Senator Yates subsequently learned that it was being reported “in the Congress Room” that a misunderstanding had arisen which would further delay the Convention, which was “far” from a final agreement. At the end of his letter, Senator Yates advises van Rensselaer to share this information with his nephew and Lansing.

- Did van Rensselaer share this intelligence with Yates and Lansing?

In a letter dated August 26, Abraham Lansing (John Lansing, Jr.’s brother) wrote to Senator Abraham Yates indicating that the “Judge and my brother” were going “to Washington County to hold Court” on August 27. “I find but little inclination in either of them to repair to Philadelphia and from their general observations I believe they will not go.”

- If so, what changed?

Abraham Lansing’s letter also confirms that Hamilton had communicated with his co-delegates about possibly returning. According to Abraham, “Hamilton will consequently be disappointed and chagrined.” In part due to these records, historians have assumed that Yates and Lansing had no interest in returning to Philadelphia.

- Was it correct to assume that Hamilton wanted Yates and Lansing to return with him?

- Perhaps he preferred that they stay put?

General questions:

- What kinds of records were destroyed in the 1911 fire?

- Do collectors have any unpublished records?

- Did Robert Yates keep a cash book? Where is it?

- How did he usually travel? By horse, by carriage or by boat?

- Did anyone see Yates traveling south in September of 1787?

- What was he thinking?

- Did he figure out what Hamilton was planning?

Robert Yates ran for governor against Clinton in 1789. Hamilton supported Yates, impressed by his loyalty to the new Constitution after it took effect.

- Why did Yates run against Clinton?

- Did Clinton blame Yates for the events of September 17?

This Post continues in Part III which explores the question, why did Yates return to the Convention? Part III attempts to synthesize what we know (and don’t know) about Judge Robert Yates and his possible motivations in the final month of the Constitutional Convention.