The Proposed Impost of 1783

(and Alexander Hamilton’s famous New York Assembly speech)

This article is the second of a multipart series about the struggle to provide an independent source of federal revenue during the 1780s. In the years preceding the adoption of the Constitution the controversy over a proposed federal impost was a defining issue in American politics. Repeated efforts to reform the Articles of Confederation ultimately failed, as the Confederation Congress attempted in vain the pay its mounting war debts.

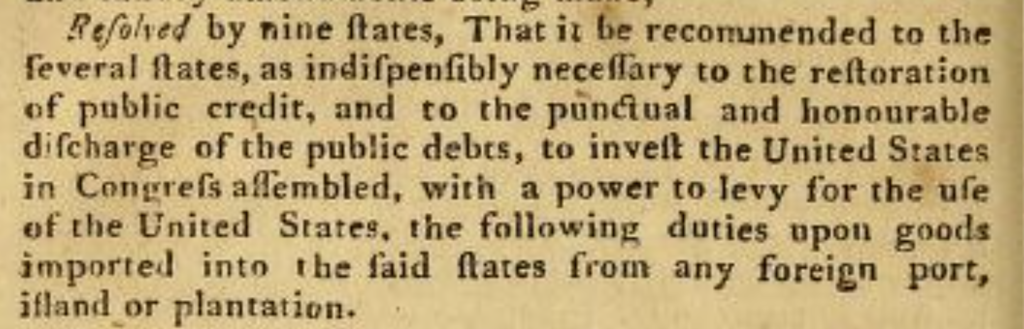

As described in Part I, the first effort to adopt a federal tariff (the “Impost of 1781”) was vetoed in 1782 by Rhode Island. A revised federal impost was proposed by the Confederation Congress on April 18, 1783 (the “Impost of 1783”). This post – Part 2 – discusses the unsuccessful multi-year effort to ratify the Impost of 1783, which was vetoed by New York. Pictured below is the text of the Impost, copied from the Journals of Congress.

Part II tells the story of Alexander Hamilton’s struggle with New York Governor George Clinton to convince his home state to agree to an impost proposal that was nearly universally acknowledged as necessary. As described by Professor John Kaminski, “[t]o some the stakes were high – perhaps the existence of the Union.”

Part II also tells the story of Alexander Hamilton’s famous February 15, 1787 speech to the New York Assembly in support of the proposed federal impost. While Hamilton ultimately failed to convince his Clintonite opponents to ratify the proposed impost, New York’s well publicized vote against the impost crystalized the issue for the nation. As described below, the impost battle in New York brought into stark relief the defects with the Articles of Confederation heading into the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia.

Part III (pending) presents the thesis that Alexander Hamilton’s support for an energetic federal government would have been well known to most (if not all) of the delegates to the Constitutional Convention. Due to the prominent role he played preceding the Convention, Hamilton’s position as a strong nationalist was no secret. As set forth in Part III, newspapers outside of New York not only reported on Hamilton’s leading role during the impost debate, but in many cases reprinted the entirety of his famous February 15, 1787 impost speech to the New York Assembly.

New York and the Impost of 1783

As discussed in Part I, Rhode Island became a national pariah when it defiantly refused to approve the Impost of 1781. As described by James Madison, the impost was rejected by the “obstinacy” of Rhode Island. Article VIII of the Articles of Confederation required amendments to be unanimously approved by all thirteen states. Thus, “[t]he small district of Rhode Island put a negative upon the collective wisdom of the continent.” Just as Rhode Island’s veto prevented the adoption of the Impost of 1781, New York would be the sole state to obstruct the second attempt at a federal impost, the Impost of 1783.

During the Revolutionary War New York was one of the first states to approve the proposed federal Impost of 1781. Nevertheless, the political dynamics in New York began to change in 1783, as it became clear that the Revolutionary War was ending.

Even as America’s military prospects dramatically improved after the battle of Yorktown in 1781, its finances continued to worsen. Realizing the urgent need to pay European and other war debts, by 1786 all states except New York had ratified the proposed Impost of 1783. As a result, the nation focused its attention on New York, the last holdout state.

Despite New York’s earlier support during the war for the Impost of 1781, New York became less willing to surrender its sovereignty to Congress after the war. It is also clear that New York was reluctant to forego its most important source of revenue, the lucrative tariffs (also known as “imposts” or “duties”) collected on goods imported through the growing port of New York.

In his biography of Governor George Clinton, Professor Kaminski explains why New York’s strong support for the Impost of 1781 was replaced by determined opposition to the Impost of 1783. When the British occupied New York City during the war, Governor Clinton had every reason to support a muscular Congress and the Impost of 1781 as a tool to win the war. With the departure of British troops after the war, Clinton’s political calculation changed.

In November of 1784 New York adopted its own state impost, which was expected to be the “cornerstone of Clinton’s recovery program.” As detailed by Kaminski, annual revenue from New York’s state impost ranged from $100,000 to $225,000. This revenue stream represented between one-third to one half of the state’s annual income. For Clinton and his base of yeomen farmers, the income from New York’s state impost on foreign imports not only helped subsidized low real estate taxes for New York farms but also allowed Clinton to pay salaries to his supporters on the state payroll.

Clinton was also displeased with Congress over New York’s disputed land claims to Vermont. In 1777, Ethan Allen and his Green Mountain Boys not only declared independence from Britain but also from New York. Accordingly, Clinton’s growing opposition to the Impost of 1783 aligned with his dissatisfaction with Congress over Vermont independence. For Kaminski, Clinton’s intransigence over the Impost of 1783 was based on an understandable, but parochial commitment to New York above the larger interests of the Union:

The governor saw the benefits derived from this horn of plenty; after all the ill treatment the state had received from its neighbors and from Congress, Clinton was reluctant to surrender New York’s most valuable asset-an asset that would greatly benefit the yeomen who formed the great bulk of the governor’s supporters.

1783 Impost Compromise by Congress

The Impost of 1783 was submitted by the Confederation Congress to the states on April 18, 1783. Ironically, the New York legislature had met in special session in July of 1782 and adopted several resolutions supporting expanded congressional taxing powers. Authored by Alexander Hamilton for submission to his allies in the New York legislature (including Philip Schuyler), the July 20 resolutions described the situation of the nation as “critical.” Recognizing that the “Source of most of our embarrassments is a Want of Sufficient Power in Congress,” Hamilton’s New York resolutions called for a general convention to revise the Articles of Confederation due to “Evils too pernicious to be hazarded.”

Thereafter, on February 21, 1783, Congress appointed a special committee including Alexander Hamilton to consider suggestions for raising revenue. As will be discussed in Part III (pending), Hamilton’s co-committee members (Madison, Rutledge, Gorham and Fitzsimmons) would later be delegates to the Constitutional Convention in 1787. All of these colleagues would be well aware of Hamilton’s unambiguous position relative to expanded Congressional powers.

The text of the Impost of 1783 was based on the committee’s March 6 Report on Restoring Public Credit & of Obtaining from the States Substantial Funds for Funding the Whole Debt of the United States. The stated goal was to renew the proposed Impost of 1781, which had been vetoed by Rhode Island.

According to Professor Kaminski, the Impost of 1783 was part of an elaborate economic program. The March 6 report “recommended to the several States as indispensably necessary to the restoration of public credit and the punctual & honorable discharge of the public debts, to vest in the U. S. in Congress assembled a power to levy for the use of the U. S., a duty of 5 PerCt. ad valorem, at the time & place of importation…”

The compromise package, amended to mollify critics, included the following components: 1) a 5% Congressional impost on most imports, with specified duties on wines, liquors, sugar, and tea; 2) limited to a twenty-five year duration; 3) to be applied for purposes of paying off war debts; 4) with revenue collectors appointed by the states, but removable by Congress, alone.

Additionally, a second component of the proposal requested that the states remit supplemental funds of $1.5M annually for 25 years to further pay down war debts. Both proposals had to be adopted together before they would take effect. States were also asked to make western land concessions the revenue from which would also be used to pay down debt. Yet another amendment proposed to revise the method used to allocate tax obligations between the states. Under Article VIII of the Articles tax quotas were based on land valuation. The allocation methodology would be changed to population (a future post will discuss this proposal which would unfortunately serve as the basis of the 3/5th compromise in Philadelphia).

Before Congress could vote on the proposed package, a preliminary peace treaty ending the war arrived on March 12, 1783. While an end to hostilities was a welcome development, the good news minimized pressure on Congress to adopt the impost. At around the same time, the so-called Newburgh Conspiracy would further complicate congressional deliberations. Another politically charged issue was the appointment and removal of tax collectors.

During the Congressional debates on the proposed impost, Madison’s notes reflect Hamilton’s “strenuous” arguments in support of a robust impost. Lacking the subtlety of other colleagues, Hamilton freely acknowledged that federal tax collectors “deriving their emoluments” from Congress would have the collateral benefit of “supporting the power of Congress” and enhancing the “energy of the federal Govt. [which] was evidently short of the degree necessary for pervading & uniting the States.” In a footnote, Madison observed that Hamilton’s remark was “imprudent & injurious to the cause which it was meant to serve.” According to Madison, opponents of the impost “smiled at the disclosure,” taking notice in private conversation that “Mr. Hamilton had let out the secret.”

Given all the effort over the years that Hamilton had put into adopting an impost, it is not surprising that he helped prepare the report to the states accompanying the April 18 impost proposal (technically several “resolutions” for adoption by the states). Hamilton served on the Committee (along with James Madison and Oliver Ellsworth) that wrote the April 26, 1783 Report on Address to States, which explained the necessity and justification for the impost proposals.

New York rejects the Impost

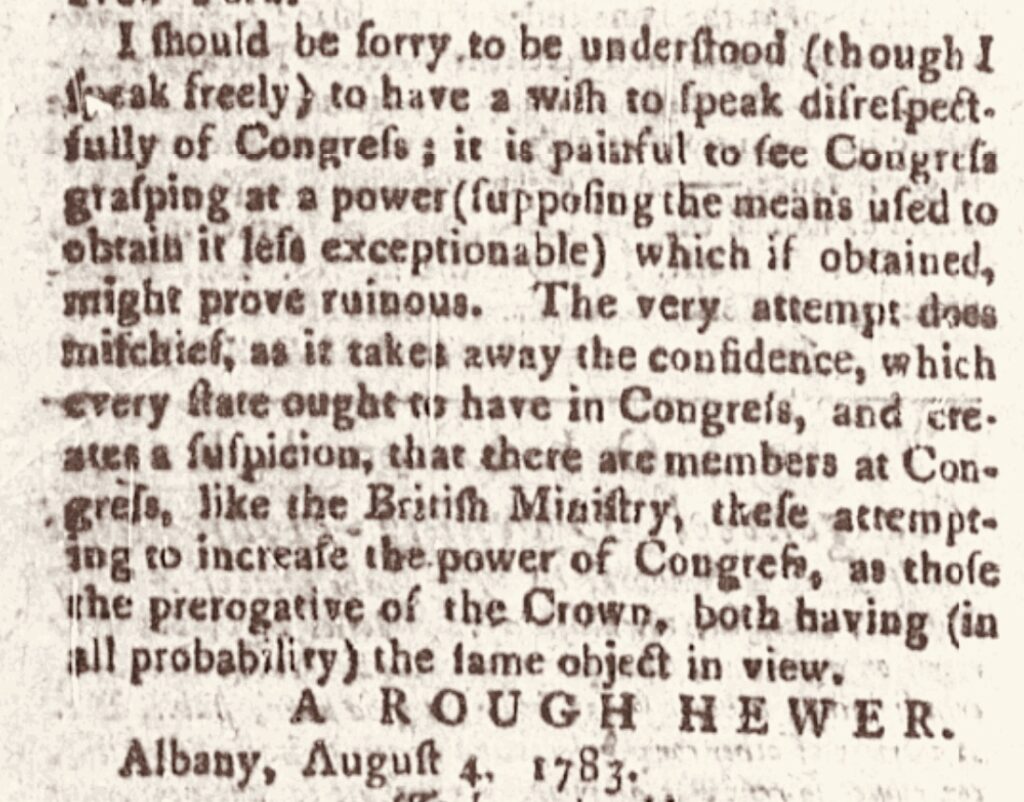

Fearful that Congress would abuse its taxing authority opponents in New York launched a series of newspaper attacks against the proposed Impost of 1783. Led by New York Senator Abraham Yates, Jr., the opposition argued that unchecked Congressional power would jeopardize state sovereignty. Yates and other opponents asserted that it was dangerous to relinquish the power of the purse to Congress. Rather, as was the practice under the Articles of Confederation, Congressional funding should only be granted on an as needed basis.

Yates’ newspaper columns were written under the pseudonym “Rough Hewer.” Examples from the New-York Gazetteer and the New-York Packet are copied below:

In particular, harkening back to abuses by British tax collectors, Yates feared that “collectors, deputy collectors, comptrollers, clerks, tide-waiters, and searchers” would create an oppressive federal bureaucracy. Others feared that unrestrained federal tax officials would be a source of corruption, intrigue and cabal. Based on these objections – and no doubt influenced as well by New York’s parochial local interest, in 1784 and 1785 the New York legislature rejected the proposed Impost of 1783. Of course, New York’s veto enabled Governor Clinton to continue collecting valuable state impost duties on ships using the port of New York.

New York reconsiders and conditionally approves the Impost of 1783 in 1786

By 1786 all states except New York had ratified the proposed impost. On February 15, 1786 Congress asked New York to reconsider. Just as Rhode Island was derided for vetoing the impost of 1781, New York was now the blamed for the continued deterioration of the federal government’s finances.

Particular ire was directed at New York by neighboring states. Imports into New Jersey and Connecticut routinely passed through the port of New York. As a result, much of the revenue raised by New York’s state impost was paid by resentful out of state consumers. New York’s low property taxes were thus subsidized by residents of other states. With limited options, New Jersey responded by declaring that it would not pay any of its congressional requisitions until New York relinquished its state import or applied the revenue “for the general purposes of the Union.” James Gorham, the President of the Massachusetts legislature (and future delegate to the Constitutional Convention) believed that the resentment over New York’s state impost would “greatly weaken if not destroy the Union.”

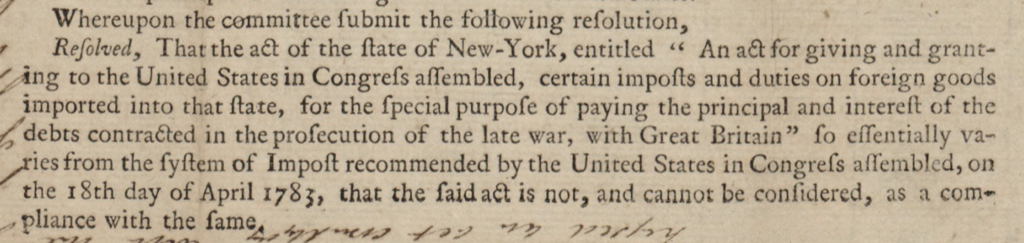

As described by Professor Kaminski, “[n]ational attention focused on the New York legislature in April 1786 as it reconsidered the impost.” On May 4, 1786 the New York legislature finally adopted the Impost of 1783, but only after imposing conditions which Congress would deem unacceptable. Rather than rejecting the proposed federal impost outright, New York reserved the exclusive power to collect the tax. It also insisted on maintaining supervision over tax collections, requiring that the impost be collected under New York procedures, including juries and appeals. The requirement that the tax be administered by state tax collectors, not federal officials, was championed by New York Assemblyman John Lansing. Click here for a discussion of Lansing’s appointment as a delegate to the Constitutional Convention.

Perhaps most objectionable to Congress, New York insisted on paying Congress with New York’s paper currency. Congress knew that if it accepted New York paper money, it would also be obligated to similarly accept depreciating paper currency from other states. Moreover, European creditors would only agree to repayment with hard currency. A Congressional committee tasked with reviewing New York’s conditional acceptance concluded on July 27, 1786 that it “so essentially varies from the system of impost recommended by the United States in Congress . . . that the said act is not, and cannot be considered as a compliance with the same.”

On August 11, 1786 Congress asked Governor Clinton to call a special session of the New York legislature to reconsider the impost. Clinton refused. As described by Congressman Rufus King of Massachusetts, Congress was “at issue with New York.” For Congressman Stephen Mix Mitchell of Connecticut the Union was tottering on “the Precipice.“

Hamilton’s Petition to the New York Legislature

After departing Congress, from 1783 to 1786, Alexander Hamilton focused on his law practice, making money and his family. Click here for a link to a post about Hamilton’s representation of loyalists and the case of Rutgers v. Waddington. In 1786, Hamilton decided to re-enter politics. In early 1786, Hamilton authored a petition to the New York legislature supporting the impost. Hamilton wrote that “Government without revenue cannot subsist.” Similarly, Hamilton had written years earlier in his Continentalist No. IV essay that, “Power without revenue….is a name.”

According to historian John Bach McMaster, Hamilton’s petition was a “clear, forcible, and concise statement of the reason why the impost should be passed, and closed with an observation as pointed as it was just.” Hamilton’s petition concluded by arguing, “That Government implies trust; and every government must be trusted so far as is necessary to enable it to attain the ends for which it is instituted; without which insult and oppression from abroad confusion and convulsion at home.”

Pictured below is a notice printed in the New York Packet alerting citizens of New York about Hamilton’s impost petition and where they could obtain copies to be signed.

When the New York legislature convened in January of 1787 the anti-Clinton forces were led by Alexander Hamilton. He was specifically elected to the New York Assembly to fight for adoption of the federal impost. Setting the stage for the pending impost fight, Hamilton and the opposition forces he led attempted to censure Governor Clinton for his refusal to convene a special legislative session. When the New York legislature approved of Clinton’s defiance of Congress, Connecticut Congressman Stephen Mix Mitchell wrote that the Assembly went out of its way “to give Congress a Slap in the face.”

Hamilton’s 2/15/1787 speech to the New York Legislature

On February 15, 1787, as the leader of the pro-impost/anti-Clinton forces, Alexander Hamilton gave a much anticipated speech to the New York Assembly. Click here for a link. Only a few months earlier, Hamilton and Madison had attended the Annapolis Convention. The report of the Annapolis Convention, authored by Hamilton, called for a Constitutional Convention to meet in Philadelphia to revise the Articles of Confederation.

By the time of Hamilton’s February speech Congress had not yet formally approved of the Annapolis Convention’s call for the Philadelphia Convention. On February 15, only a minority of states had appointed delegations to Philadelphia. This pending question provided a dramatic backdrop for Hamilton’s speech.

According to historian Allan Nevins, many of the most distinguished Americans were in the halls to watch Hamilton’s speech. It bears mentioning that in 1787, Congress met in the same building as the New York legislature. Ron Chernow’s biography observes that Hamilton, “made a heroic stand in the New York Assembly to arrest the country’s deteriorating finances, supporting the 5 percent impost tax proposed by Congress.”

In a powerful speech lasting more than an hour, Hamilton systematically examined each of the objections to the federal impost. Hamilton then asked, “Can our national character be preserved without paying our debts. Can the union subsist without revenue? Have we realized the consequences which would attend its dissolution?” Hamilton answered that:

If these states are not united under a federal government, they will infalliably have wars with each other; and their divisions will subject them to all the mischiefs of foreign influence and intrigue.

As described by Chernow, Hamilton “unfurled a grim panorama of America under the confederation.” Hamilton explained that “our foreign creditors must and will be paid.” Hamilton worried that, “They have power to enforce their demands, and sooner or later they may be expected to do it.”

For Nevins, Hamilton’s speech was “one of the greatest speeches of his life.” According to Hamilton biographer John C. Miller, “Hamilton’s eloquence did not make the slightest impression on the Clintonians.” After Hamilton concluded his speech, the Clintonites “sat stolidly in their seats and, without deigning to answer him, proceeded to kill the impost.” Nevertheless for Miller, Hamilton’s impost speech “more than any other act prior to his appointment as Secretary of Treasury, brought him into the public eye.”

Chernow writes that Hamilton’s speech was met with “stony stares from the Clintonians, who responded in insulting fashion” by promptly voting against his motion, without any debate.

The speech was widely reprinted around the nation in newspapers and in the American Museum (a Philadelphia magazine with a national subscriber base). The editors who reprinted Hamilton’s speech frequently mentioned that, “The members opposed. . . made no attempt to justify their votes by arguments or to invalidate those cogent ones alleged in favor of the measure by Col. Hamilton. . . the impost was strangled by a band of mutes” According to an essay by Rough Carver in the NY Daily Advertiser on 9/3/1787, Hamilton’s speech was met with “contemptous silence.” While the identity of Rough Carver is unknown, the pseudonym pokes fun at Abraham Yates, who wrote as Rough Hewer.

Immediately following Hamilton’s speech, James Madison wrote to Thomas Jefferson on February 15, 1787 to report that the New York Assembly “has just rejected the impost which has an unpropitious aspect.” Thereafter, Madison informed George Washington on February 21, 1787 that New York’s vote “put a definitive veto on the Impost.”

For Professor Akhil Reed Amar, “New York’s no doomed the revenue plan and was for many Americans the last straw, confirming the imbecility of the Confederation and the practical impossibility of reforming the Articles from within.” According to Alexander Hamilton’s son, John Church Hamilton, “The vote of the New York legislature on the impost decided the fate of the Confederation.” For Hamilton biographer Forrest McDonald, despite his “masterful speech” Hamilton “won the argument and lost the issue.”

In his biography of Alexander Hamilton, Henry Cabot Lodge wrote that even as the impost was defeated, “Hamilton shone with the full lustre of eloquent argument.” Lodge was not only a historian, but would be subsequently elected to the United States Senate in 1892. In Lodge’s estimation:

Clinton and his followers gave the finishing stroke to the confederacy, completed its wreck, and left the country to choose between anarchy and union on a new basis. They builded better than they knew.

For historian Thomas C. Cochran, the New York vote against the impost sounded the “death knell of the Confederation.”

Two days later, after the impost was voted down, Hamilton succeeded with an important motion in the New York Assembly. According to Philip Schuyler (Hamilton’s father-in-law), some of the members of the New York legislature who voted against the impost felt “ashamed of their conduct, and wished an opportunity to make some atonement.” Perhaps for this reason, the New York legislature agreed to instruct New York’s congressional delegation to support a resolution recommending that states send delegates to Philadelphia.

As described by Professor Kaminski, Hamilton took advantage of the inevitable defeat of the impost. “He used the legislative forum on the impost as a platform on which to advocate [for] a strengthened Congress, a mutual understanding among the states for each other, and a denunciation of those narrow-minded politicians who put state interests above the nation’s welfare.”

A few weeks after his speech, Hamilton received a congratulatry letter from New York Chancellor Robert R. Livington: “While I condole with you on the loss of the impost I congratulate you on the lawrels you acquired in fighting its battles.” Margaret Livingston wrote to her son that as a result of Hamilton’s speech, he “was called the great man. Some say he is talked of for G[overnor].”

The following month, the Marquis de Lafayette wrote to Hamilton indicating that, “Of you I Hear By some of our friends, and in the News Papers.” While Lafayette’s April 12, 1787 letter doesn’t mention Hamilton’s impost speech per se, it is reasonable to conclude that the newpaper articles that Lafayette was referring to contained reports of Hamilton’s February 15 speech.

Copied below is an example of the full text of Hamilton’s speech appearing on the front page of the New York Daily Advertiser. Also pictured below is an advertisement for the American Museum magazine. The advertisement features a reprinting of “Colonel Hamilton’s speech in the Assembly of New-York, on the Propriety of investing Congress with Power to levy the Impost.”

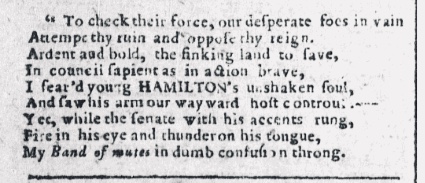

Hamilton’s speech was not only widely reported in the press, it migrated into the popular culture of the day. While largely unknown to modern readers, the Anarchiad was a popular and widely reprinted satirical poem that appeared serially in the New Haven Gazette from October 26, 1786 through September of 1787. Copied below is an except from the lengthy “mock-epic” poem praising Hamilton and his celebrated speech:

In this passage, the young Hamilton confronts the villain Anarch. It was not lost on readers that the character Anarch was modeled after New York Governor Clinton, who worked for a future “when every rogue shall literally do what is right in his own eyes.”

“Impost begat Convention”

During the New York ratification debates in 1788 Alexander Hamilton described the importance of the struggle over the failed federal impost. According to Hamilton, “Impost begat Convention.” In other words, the failure of the Impost of 1781 and 1783 gave rise to the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787. Professor Calvin Johnson argues that the “first mission of the Constitution” was to give Congress a tax of its own to help satisfy Revolutionary War debts. Indeed, some have speculated that if the impost proposals had not been vetoed by Rhode Island and then New York, the Constitution as we know it today would never have been necessary.

In fact, the first power granted to Congress under Article I, Section 8 is the “Power to lay and collect Taxes, Duties Imposts and Excises to pay the Debts and provide for the common Defense and general Welfare of the United States….” It is also noteworthy that Article I, Section 10 prohibits states from passing their own imposts on duties or exports, without the consent of Congress.

As described by historian Richard Beeman, “[a]t nearly the exact moment that New York was dealing a death blow to plans for a federal impost,” Shays’ Rebellion erupted in Massachusetts. Secretary of War Henry Knox would subsequently observe that, “[t]he insurrections of Massachusetts and the opposition to the impost by New York, have been the corrosive means of rousing America to an attention to her liberties.” According to Beeman, by vetoing the impost New York did more than merely threaten the well-being of the young nation:

It brought into bold relief an even more painful reality: the very structure of the Articles of Confederation, which required that any meaningful change in the country’s federal charter receive the unanimous approval of the states, was fundamentally defective.

Thus, the stage was set for the Constitutional Convention. This post continues in Part III (pending), which argues that Alexander Hamilton’s decade long effort to strengten Congress would have been no secret in Philadelphia.

Additional Reading and Sources:

Documentary History of the Ratification of the Constitution, New York, Introduction (2003)

The Reluctant Pillar: New York and the Adoption of the Federal Constitution (Schechter, ed., 1984)

George Clinton, Yeoman Politician of the New Republic, John P. Kaminski (1993)

Commandeering and Constitutional Change, Wesley J. Campbell, Yale Law Journal (2013)

The American States During and After the Revolution, 1775-1789, Allan Nevins (1924)