The proposed Federal Impost of 1781

During the 1780s one of the foremost issues facing the nation was the dire need for Congress to raise revenue. Beginning in 1781 Congress proposed the creation of a 5% tariff on imports (the “Impost of 1781″). For the next seven years the proposed federal impost was at the center of a national debate over Congressional power and state sovereignty.

Amendments to the Articles of Confederation required unanimous approval by all states. By the fall of 1782 every state except Rhode Island had approved the proposed federal impost. Despite Rhode Island’s veto, Congress tried again the following year with a scaled down impost proposal (the “Impost of 1783”). Nevertheless, this time the Impost of 1783 was defeated by New York.

As set forth below, the failure of the proposed federal impost made national headlines and was a primary motivation leading states to send delegates to the Constitutional Convention in 1787. As later described by Alexander Hamilton, “Impost Begat Convention” – meaning that the failure to adopt the proposed federal impost gave rise to Constitutional Convention.

This blog is the first of a three part series about the impost proposals of the 1780s. Part one provides background about the failure of the proposed “Impost of 1781” which was vetoed by Rhode Island and Impost of 1783 which was defeated by New York.

Part 2 addresses the Impost of 1783. The effort to adopt the impost in New York was spearheaded by Alexander Hamilton. Part 2 explores Hamilton’s role in the impost debate, including his widely reported speech of February 15, 1787 before the New York Assembly. Despite his best efforts, Hamilton and his allies in the New York Assembly failed to secure New York’s adoption of an impost that was acceptable to Congress. Nonetheless, Hamilton succeeded in his efforts to leverage the impost’s failure as a justification for states to send delegates to the Constitutional Convention in 1787.

Part 3 (pending) makes the argument that Hamilton’s prominent role supporting the proposed impost made him a well known national figure. In other words, when Hamilton arrived at the Philadelphia Convention in 1787, it is almost certain that the majority – if not all – of the other delegates either knew Hamilton or knew of his well publicized positions as a leading nationalist.

Impost debate

Under the Articles of Confederation Congress lacked an independent revenue source and was entirely dependent on the states for funding. As described by Alexander Hamilton in Federalist 30, the federal government was rendered “impotent” because it did not have its own “general power of taxation.” As a result it was chronically unable to pay its debts and at risk of defaulting to its European creditors, which contributed to the “imbecility of our Union.”

As early as 1780 Hamilton observed that, “[t]he fundamental defect is a want of power in Congress.” For Hamilton “the confederation itself is defective and requires to be altered; it is neither fit for war, nor peace.” Hamilton elaborated that an underlying defect was “[t]he idea of an uncontrolable sovereignty in each state” which will “make our union feeble and precarious.” Click here for a link to Hamilton’s 3 September 1780 letter to New York Congressman James Duane.

Even after winning the Revolutionary War the Founders still had reason to fear. Spread out primarily along the Atlantic coast, America was vulnerable to predation from Britain, Spain, and France. According to Professor Calvin Johnson, while Congress was obligated to provide for the common defense, “it could not pay for a cannon, a soldier, or a sloop.” As described by Edward Rutledge of South Carolina, “[w]ithout a ship, without a soldier, without a shilling in the federal treasury” and without a viable government to obtain one, “we hold the property that we now enjoy at the courtesy of other powers.”

Without independent taxing authority, Congress depended on “requisitions” from the states. Under the Articles of Confederation Congress was vested with the power to issue paper currency and borrow, but it lacked the power to tax or enforce compliance with requisition requests. In theory, requisition payments were mandatory. Yet, in practice the states increasingly treated Congressional requisitions as “mere recommendations,” not “sacred & obligatory,” as claimed by James Madison. The requisition of 1786 was almost entirely ignored by the states. While Congress requested $3,800,000 it only collected $663 in the final requisition preceding the adoption of the Constitution.

Hamilton would later describe the requisition process as “one of the maddest projects that was ever devised.” Hamilton worried that trying to collect requisitions from a recalcitrant state ran the risk of a civil war, “a nation at war with itself.” For George Washington, after the imperative of the Revolutionary War ended requisitions were a “perfect nihility.” As described by Washington in a letter to Virginia Congressman Joseph Jones in 1780:

One State will comply with a requisition of Congress; another neglects to do it; a third executes it by halves; and all differ either in the manner, the matter, or so much in point of time, that we are always working up hill, and ever shall be.”

Leading into the Constitutional Convention in the spring of 1787, James Madison famously prepared his list of “Vices” describing the defects with the Articles of Confederation. At the top of Madison’s list was the inability of Congress to raise revenue. Madison wrote that the refusal by states to comply with Congressional requisitions “may be considered as not less radically and permanently inherent in, than it is fatal to the object of, the present System.” Hamilton of course agreed and had been arguing since his 1780 letter to Duane that Congress had but the “shadow of power” which resulted in “a want of sufficient means at their disposal to answer the public exigencies…”

The nationalists who supported the proposed impost understood that it was the most practical solution for the nation’s increasingly problematic fiscal woes. A federal impost could be efficiently collected at American ports before ships were unloaded. Only a relatively small number of customs officers were required to collect imposts, compared to the complexity of assessing internal taxes based on the value of land or other decentralized tax programs.

The proposed impost made sense as a federal tax. Otherwise, if each state assessed its own imposts on foreign commerce, the states with deep water ports would be incentivized to undercut each other to attract foreign commerce. Predictably, this is precisely what occurred after the Revolutionary War, as states began to treat each other as commercial rivals. As explained by Hamilton in Federalist 12, if the impost were applied nationally by the federal government, it could be efficiently and less expensively implemented than if the states attempted to do so separately.

As described below, the failure to amend the Articles of Confederation to grant the requested federal impost during the 1780s would ultimately expose the reality that the Articles were fundamentally beyond repair. According to Professor Wesley Campbell, given the horrendous condition of federal finances, the impost controversy became a “defining issue in American politics.” The impost controversy would also serve as a recurring theme during the ratification debates.

Robert Morris’ Plan

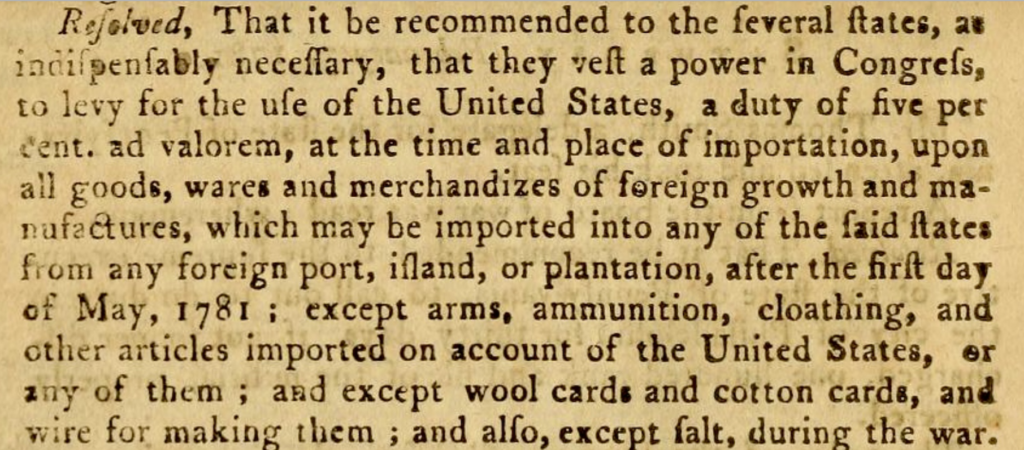

According to Professor John Kaminski, the first serious effort to strengthen the Confederation Congress began in February of 1781. On February 3, 1781 Congress proposed a 5% federal impost until the debts of the United States were extinguished. By mid-1782, all states ratified the proposed Impost of 1781, except for Rhode Island.

Professor Jack Rakove theorizes that the impost was purposefully phrased as a constitutional guarantee of independent federal authority. According to the proposed text, it was “indispensably necessary” that the states “vest a power in Congress to levy” the 5% impost. If so, it was “apparently designed to obviate the possibility tht the states could repeal their acts of authorization as they might any piece of legislation.”

The impost – a central feature of the nation’s financial plan in 1781 – was championed by financier Robert Morris. The new Department of Finance was created by Congress on February 7, 1781, along with the departments of War and Foreign Affairs. An influential, self made, and prominent Philadelphia merchant, Morris was unanimously selected to be the first Superintendent of Finance. Morris accepted the post in mid May of 1781, two months after the Articles of Confederation were finally ratified in March of 1781.

In “Circular Letters” sent to state governors Morris campaigned for adoption of the impost. He explained the British were relying on the “derangement of our finances” but “when revenue is given, that hope must cease.” Morris elaborated that European bankers in France and the Netherlands were closely watching the impost vote. If it failed they would conclude “that we are unworthy of Confidence, that our Union is a Rope of Sand…” In an unsolicited letter dated April 30, 1781, Alexander Hamilton wrote Morris a detailed outline of Hamilton’s own financial proposals.

In 1781 Congress requested $3,000,000 in requistions but only received $39,138. As described by historian Joseph Ellis, it was a standing joke in Congress that “binding Requisitions are as binding as Religion is upon the conscience of wicked Men.” Nevertheless, Morris succeeded in securing overseas loans, which he supplemented with his own funds.

Veto of the Impost of 1781 by Rhode Island

Athough tweleve states had approved the proposed Impost of 1781, a change in the Rhode Island delegation led to its defeat. David Howell, a newly elected representative and math instructor at Rhode Island College (later Brown University), argued that the impost would make the states “mere provinces of Congress and tending to the establishment of an aristocratical or monarchical government.” In Howell’s mind, Congress was “a foreign government.” Howell equated the impost to the British Townshend Acts that precipidated the Revolution. Howell and his allies feared that the impost would be a “Yoke of Tyranny fixed on all the staes, and the Chains Riveted.”

The proposed Impost 1781 died in November of 1782 when it was formally vetoed by the Rhode Island Assembly. As described by James Madison, the impost was rejected by the “obstinacy of Rhode Island.” Thereafter, in December of 1782, Virginia repealed its earlier approval. Other states, including New York, withdrew approval in early 1783, recognizing that the impost no longer stood any chance of adoption.

In a letter from the Speaker of Rhode Island’s Assembly to Congress, William Bradford explained three reasons for vetoing the impost. According to Bradford, the impost violated state sovereignty by 1) placing an unequal burden upon the commercial states; 2) the impost would violate the Rhode Island constitution by “introduce[ing] into this and the other states, officers unknown an unaccountable to them;” and 3) the impost would make Congress “independent of their constituents [the states],” making the impost “repugnant to the liberty of the United States.”

The fact that the nation’s smallest state would sabotage the desparately needed impost exemplified everything that was wrong with the Articles. A stunned Congress attempted to salvage the impost proposal by sending a delegation to Rhode Island. A Congressional committee, consisting of Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and Thomas FitzSimons, prepared a response to Bradford’s letter. Written by Hamilton, the December 16, 1782 committee report set forth a vigorous defense of the impost proposal.

Responding to each of Rhode Island’s objections, the commitee report explained that the impost was not a burden on the citizens of Rhode Island since it was only paid by the consumers of imports. “[T]he rich and luxrious pay in proportion to their riches and luxuries, the poor and parsimonious in proportion to their poverty and parsimony.”

The objections advanced by Rhode Island “would defeat all the provisions of the Confederation and all the purposes of the union. The truth is that no Foederal constitution can exist without power.” Hamilton argued that the impost was both within the letter and spirit of the confederation. Congress was “empowered to borrow money for the use of the United States, and by implication to concert the means necessary to accomplish the end.” Hamilton observed that “[t]he conduct of the war is intrusted to Congress and the public expectation turned upon them without any competent means at their command to satisfy the important trust.”

Although the Rhode Island Assembly remained adament, Hamilton’s report was approved by Congress. Ironically, Rhode Island’s Congressional delegation voted in favor of Hamilton’s report. Professor Nathan Coleman argues that Hamilton’s committee report laid the foundation for his expansive thinking about Congressional powers.

Due to its veto of the impost Rhode Island became a national scapegoat. Rhode Island was described as a “perverse sister” whose “injured the United States more than the worth of that whole state.” Newspapers and commentators viewed Rhode Island’s veto as “shameful,” suggesting that this “cursed State, ought to be erased out of the Confederation, and… out of the earth, if any worse place could be found for them.”

For Melancton Smith, a New York Congressman, Rhode Island was an illustration of “political depravity,” “genuine infamy,” and “a wicked administration.” According to Noah Webster, Rhode Island was that “little detestable corner of the continent” that was otherwise known as “Roques Island.”

This post continues in Part II which discusses the second attempt to adopt a federal impost in 1783. This time, New York would step into Rhode Island’s shoes as the sole, obstinate, holdout state. Alexander Hamilton was elected to the New York Assembly in 1787 specifically to lead the charge for the adoption of a federal impost. Part II also discusses Alexander Hamilton’s widely reported February 15, 2017 speech before the New York Assembly. Even though New York would refuse to adopt the Impost of 1783, Hamilton would use the impost battle as a platform to advance the nationalist agenda on its journey to Philadelphia.

Additional Reading:

Journals of Congress, 1781 (containing the Impost of 1781)

Attempts to Amend the Articles (Center for the Study of the American Constitution)

Documentary History of the Ratification of the Constitution, Rhode Island, Introduction (2011)

The Nationalists at the Continental Congress, Nathan Coleman (November 8, 2017)

Commandeering and Constitutional Change, Wesley Campbell, The Yale Law Journal