Yates’ return trip to the Convention

Why?

Professor John Kaminski, Adam Levinson, Esq., Sergio Villavicencio

In the forward to the book Ratifying the Constitution, historian Forrest McDonald observed that the “corpus of historical literature on the drafting of the United States Constitution is enormous.” Nevertheless, we have been thrown a curve ball by the recent discovery that New York delegate Robert Yates attempted to return to the Constitutional Convention in September of 1787. This stunning new revelation, emerging from an otherwise well trodden period, suggests that much may remain to be learned about a formative period in American history.

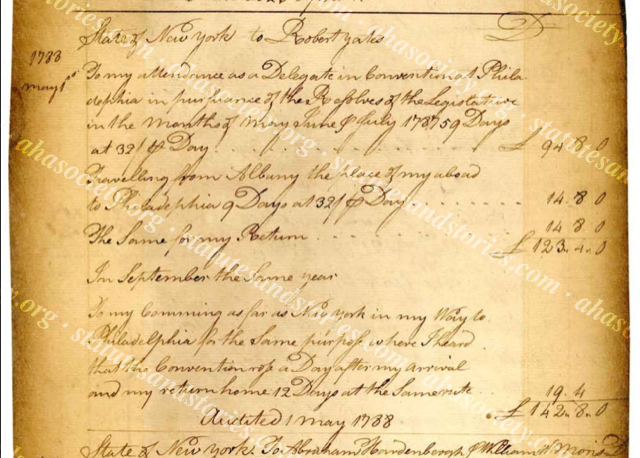

This article is the third – and admittedly still incomplete – effort to synthesize what we know (and don’t know) about Judge Robert Yates and his motivations in the final month of the Constitutional Convention. According to the recently discovered records of the New York State Auditor General, Judge Yates requested payment of £ 19 & 4 shillings for 12 days of travel in September of 1787, following his aborted effort to return to the Constitutional Convention. We have labeled this dramatic new event: “Yates returns.” In our view, this new evidence requires a careful reexamination of traditional assumptions about a key month in American history.

As reported on November 9, Part I broke the news and provided background about the discovery. In particular, Part I illustrated how the Federalist supporters of the Constitution based their early marketing efforts on the highly regarded reputation of the Philadelphia delegates and the useful fiction that the Constitution was “unanimously” approved by all state delegations in attendance. Part II continued the discussion by asking a series of questions that logically flow from Yates’ return trip.

Part II presumes that Judge Yates attempted to return to Philadelphia to check Hamilton and/or stop Hamilton from signing the Constitution. Part II further presumes that Hamilton’s arrival in Philadelphia on September 6 and/or election to the Committee on Style on September 8 may have been the trigger for Yates to return from Albany. While admittedly conjecture, it is not unreasonable to infer that another delegate or other third party notified Robert Yates of Hamilton’s arrival in Philadelphia. One can only speculate at this point who notified Yates? In other words, was there a mole at the Constitutional Convention? Was Governor Clinton spying on Hamilton? It is also logical to ask: Did Yates ask Lansing to join him? If not, why not?

This blog post (Part III) focuses on Robert Yates and John Lansing, Jr., and asks the question why would Yates have decided to return? As described below, Yates and Lansing wrote a detailed letter to Governor Clinton on 21 November 1787 describing their reasons for leaving the Convention in July. While their letter to Clinton says nothing about Yates’ return trip in September, it provides useful insights into Yates/Lansing’s thinking in the months preceding the New York ratification convention.

Conventional Understanding of Yates and Lansing’s Agenda

Until the November 9th discovery, it was universally recognized by historians that Yates and Lansing abandoned the Convention on July 10, never to return. Cecil L. Eubanks in the book Ratifying the Constitution captures the prevailing understanding (based on the historical record as it existed until last week) as follows:

Both Yates and Lansing left quietly in early July, and largely because it appeared that the convention would propose a strong centralized government, they did not return.

While Yates and Lansing may have left quietly, historian Pauline Maier assumes that Yates left the federal convention “in disgust.” This view is supported by Maryland delegate Luther Martin‘s assessment that Yates and Lansing “uniformly opposed the system” and left “despairing of getting a proper one brought forward, or of rendering any real service, they returned no more.”

Understandably, the traditional understanding of New York’s role in the drafting of the Constitution is that New York’s delegates were not major actors in Philadelphia. This result is evident from the internally conflicted composition of the New York delegation. While Alexander Hamilton was a leading nationalist who drafted the report of the Annapolis Convention, Robert Yates and John Lansing, Jr., were purposely selected for the New York delegation to check Hamilton. Click here for a discussion of the appointment of the New York delegation. While not the subject of this post, click here for a discussion of the Hamilton Authorship Thesis (HAT) which proposes that Alexander Hamilton was the principal draftsman of the Constitution’s 17 September 1787 Cover Letter. Taken together the HAT thesis and the “Yates returns” discovery suggest that additional research is warranted into the New York delegation and its role in Philadelphia.

The conventional understanding of New York’s limited role in Philadelphia starts with New York’s powerful, parochial governor, George Clinton. According to Pauline Maier, the author of the book Ratification: The People Debate the Constitution 1787-1788, “[t]he number-one enemy for those who fought for the Constitution – the man who defined the meaning of ‘anti-federalist’ – was not Patrick Henry but New York governor George Clinton.”

It is commonly accepted that Clinton was content with the status quo in 1787. Likewise, it cannot be denied that Clinton would become a leading anti-Federalist. As described by historian Susan Westbury, Governor Clinton, “in turning away from the intense nationalism of his Revolution War years, had become a politician dedicated to his state’s interests and to the well-being of his yeoman-farmer supporters.” The title of Professor Kaminski’s biography of George Clinton emphasizes this narrative about the powerful New York Governor’s political base, George Clinton: Yeoman Politician of the New Republic.

Perhaps the best evidence of New York’s proto-anti-Federalist perspective in the period preceding the Constitutional Convention is New York’s opposition to the proposed federal impost which would have provided the Confederation Congress with an independent revenue source (tariffs). Click here for a discussion of the proposed federal Impost of 1783, which was defeated by New York, the sole holdout state, in February of 1787. Other formidable evidence of New York’s strong anti-Federalism includes the large anti-Federalist majority elected to the New York ratification convention in 1788 and the hard fought battle for ratification led by Alexander Hamilton.

As described by Professor Kaminski in the DHRC, Vol XIX, Governor Clinton and his allies:

felt that New York had contributed more than its fair share of men and money toward the war effort. Since both the state and federal financial crises could probably not be solved simultaneously, and since it appeared that other states would not contribute significantly to alleviate the federal financial problem, Clintonians decided to concentrate on New York’s problems.

For strategic reasons, New York appointed only three delegates to the Constitutional Convention. By contrast, Virginia embraced the Constitutional Convention by appointing a seven member delegation which included arguably the most famous American, George Washington, along with Virginia governor, Edmund Randolph. Pennsylvania sent the largest state delegation, which included Benjamin Franklin among Pennsylvania’s eight prominent members.

The reasons for the appointment of Yates and Lansing to the three member New York delegation was not a secret. As correctly summarized by James Madison in a letter to George Washington sizing up the state delegations, Yates and Lansing were “pretty much linked to the antifederal party here, and are likely of course to be a clog on their colleague [Hamilton].” It is noteworthy that Madison didn’t merely indicate that Yates and Lansing were likely to counter Hamilton, Madison emphasized that this was “of course” predictable. Madison similarly observed in a letter to Governor Randolph that Yates and Lansing “lean too much toward State considerations to be good members of an Assembly….”

Philip Schuyler, Alexander Hamilton’s father-in-law, in a letter dated 13 March 1787 provides a contemporaneous view from New York as to why the composition of the New York delegation did not augur well. According to Schuyler, the objectives of the “junto” of New York Clintonians, included:

a state impost, no direct taxation, keep all power in the hands of the legislature, give none to Congress which may destroy our influence, and cast a shade over that plenitude of power which we now enjoy.

Schuyler predicted that the Clintonians could be expected to “propagate that every additional power conferred on that body [Congress] will be destructive of liberty…the people will be alarmed, and their representatives will be deterred from affording their assent….” Schuyler also anticipated that the Clintonians would invent “a variety of pretenses” for not acceding to the Constitution.

Yates never disclosed why he attempted to return to Philadelphia. Until recently nobody imagined that he would venture back. Nevertheless, we can easily deduce he was not returning to sign the Constitution with Hamilton. Rather, as described by Stanley Elkins and Eric McKitrick in their famous 1961 article about the founding generation, Governor Clinton decided to send two “rigid state particularists” to the Convention “to make sure that Hamilton would not accomplish anything.”

Yates and Lansing at the Convention

Not surprisingly, during the Convention Yates and Lansing consistently voted together against Hamilton. As described by Professor Kaminski, Yates and Lansing “voted with a minority of delegates who favored amending the Articles of Confederation in order to invest Congress with limited additional powers that would not unduly shift sovereignty away from the states.”

Yates traveled with Hamilton to the Convention. One can speculate whether Yates did so to keep an eye on Hamilton. Before Lansing arrived, on May 30, Hamilton and Yates split their vote on the threshold question of whether a “national government” ought to be established consisting of a “supreme Legislative, Executive and Judiciary.”

Two particularly stark examples of the division within the New York delegation stand out. According to James’ McHenry’s notes, on May 29 Alexander Hamilton commented about the Virginia Plan that “it struck him as a necessary preliminary inquiry…whether the United States were susceptible of one government….” In other words, Hamilton was fundamentally calling into question the underlying role of state governments, while Judge Yates was a committed supporter of New York state sovereignty. According to Gunning Bedford’s notes on May 29, Governor Randolph acknowledged that the proposed Virginia Plan intended to form “a strong, consolidated Union in which the Idea of States should be nearly annihilated.” These sentiments, of course, would be highly problematic for Yates and Lansing.

A second example of the conflict within the New York delegation was the issue of whether the president (“executive”) should be granted an absolute veto (“negative”). While James Wilson and Alexander Hamilton made the motion to “to give the Executive an absolute negative on the laws,” New York (and all the states) voted on June 4th against Hamilton’s motion. The Convention, including New York, then voted for a 2/3 congressional override of presidential vetoes.

Tellingly, during the debate on June 16 over the Virginia Plan, John Lansing indicated that New York “would never have concurred in sending deputies to the convention, if she had supposed the deliberations were to turn on a consolidation of the States and a National Government.” Lansing warned that the states “would never sacrifice their essential rights to a national government.” To emphasize his point he thus inquired, “was it probable that the States would adopt & ratify a scheme, which they had never authorized us to propose? and which so far exceeded what they regarded as sufficient?”

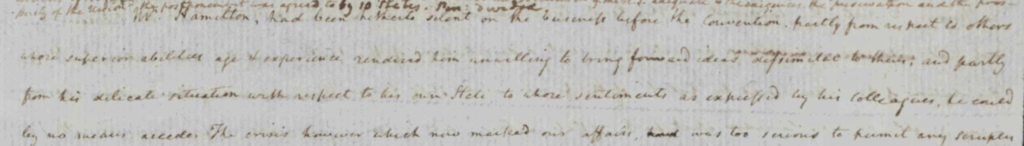

When Hamilton gave his famous all day speech on June 18, he began by noting that he had hitherto been silent, due in part to his “delicate situation with respect to his own State.” Hamilton put an exclamation mark on the deep dissension within his delegation when he mentioned that the “sentiments as expressed by his Colleagues [Yates and Lansing], he could by no means accede.”

Hamilton then proceeded to give the most nationalist speech of the entire Convention. Yates and Lansing likely disagreed with almost everything Hamilton said in his famous speech. On June 20th, Yates recorded in his notes the following deep reservations:

I am clearly of opinion that I am not authorized to accede to a system which will annihilate the State governments and the Virginia plan is declarative of such extinction.

Quick footnote: It is important to indicate that questions have been raised about the integrity of Yates’ notes since the original manuscript has never been found. Professor Westbury, for example, distinguishes between the two versions published by Edmond Genet in 1808, which may have been edited to slander Madison who was running for President.

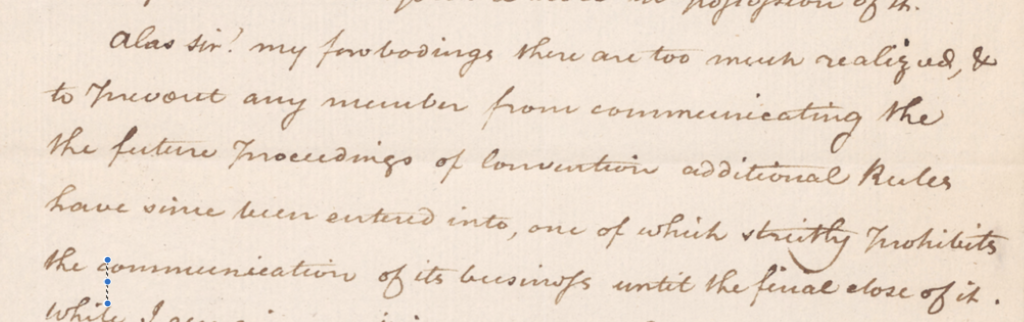

Further reinforcing our understanding of Yates’ thinking is a letter that he wrote to his anti-Federalist uncle, Abraham G. Yates, Jr., who was serving as a member of the Confederation Congress at the time. On June 1, Judge Yates confided to his uncle, “Alas sir! my forebodings there are too much realized.” While Yates was bound by the Convention’s rules of secrecy, his “forebodings” together with his use of an explanation point did not bode well for participation. Indeed, Judge Yates indicated that, “[h]ow long I shall remain future events must determine. I keep in the meanwhile an exact journal of all its proceedings.” A future post will explain how we can deduce from this letter that Judge Yates was confidentially sharing information with Governor Clinton in violation of Convention rules.

It also appears that John Lansing was sharing intelligence with his family during the Convention. In a letter dated August 26, Lansing’s brother, Abraham Lansing, wrote to Abraham Yates that “I find but little inclination in either of them to repair again to Philadelphia. and from their general observations I believe they will not go.” Abraham Lansing sarcastically predicted that “Hamilton will consequently be disappointed and chagrined.” Little did the Yates and Lansings realize how Hamilton would later take advantage of – and may have welcomed – his autonomy during the closing days of the Convention as the only New York delegate in attendance in September.

As described in Part I, Hamilton helped propagate what Professor Robert A. Ferguson has described as a “useful fiction” of unanimity when the Constitution was signed. For Ferguson, the Federalist marketing campaign to sell the Constitution perpetuated a “myth of glorious harmony” which was used to elicit and enforce allegiance. In the book Original Meanings, Professor Jack N. Rakove explains that “[a]ppeals to the collective stature of the Convention and the prestige of Washington and Franklin” were important elements of the “Federalist strategy.”

On the subject of strategy, one can only wonder what Hamilton had in mind when he wrote two letters to Rufus King in August. King was one of Hamilton’s allies at the Convention who would serve with Hamilton on the Committee on Style. In both letters, Hamilton asked King to keep Hamilton posted as to when the Convention would be concluding. By letter dated August 20 Hamilton asked King to advise “when your conclusion is at hand; for I would choose to be present at that time.” When Hamilton underscored the word “conclusion,” it is unclear why he didn’t want to arrive too early.

A week later on August 28 Hamilton was curiously very specific but also very vague. Consistent with the August 20 letter Hamilton indicated that he wanted to know “when there is a prospect of your finishing….” Interestingly, Hamilton emphasized that he wanted to be at the Convention “for certain reasons, before the conclusion.” The Hamilton Authorship Thesis (HAT) intuits that Hamilton knew exactly why he wanted to return. According to the HAT thesis, Hamilton had very specific reasons in mind – to write the Cover Letter for Washington’s signature. It is also plausible that Hamilton didn’t want to return too early, to avoid alerting Yates, Lansing and Clinton to his plans.

After the Convention, during the New York ratification debates, Judge Yates would explain that he only reluctantly attended the Constitutional Convention out of a sense of duty. According to John McKesson’s notes of the New York Ratification Convention debates on June 30, 1788, Yates admitted that, “I went with great Reluctance—I held it my Duty to go….” Judge Yates’ brother predicted in a letter dated August 26 to John Lansing’s uncle that, “I find but little inclination in either of them to repair again to Philadelphia and from their general observations I believe they will not go.”

Thus, based on Yates’ own admissions, he attended the Convention “with great reluctance.” While in Philadelphia he confidentially admitted to his uncle that his “forebodings” were “too much realized” at the Convention. While Yates never spoke at the Convention, he kept what he described as an “exact journal,” presumably so that he could use it to defend his actions and minority positions.

Yates and Lansing’s letter to Clinton

In a letter dated 21 December 1787 Yates and Lansing officially described why they left the Convention, albeit almost six months after the fact. In their letter Yates and Lansing explained that it had become clear that the delegates to the Convention would defy their instructions which should have confined them “to the sole and express purpose of revising the articles of Confederation.”

According to Yates and Lansing’s explanatory letter:

[W]e have the strongest apprehensions, that a government so organized, as that recommended by the convention, cannot afford that security to equal and permanent liberty, which we wished to make an invariable object of our pursuit….A persuasion, that our further attendance would be fruitless and unavailing, rendered us less solicitious to return.

According to Professor Kaminski, Yates and Lansing justified their departure as a matter of principle. For Yates and Lansing the proposed Constitution was particularly problematic because it would create a new, powerful, “consolidated” federal government sought by Hamilton. Yates and Lansing explained that the proposed “system of consolidated Government” was not “in the remotest degree” authorized or contemplated by the New York legislature.

Yates and Lansing further objected, as predicted by Philip Schuyler, that the Constitution would be “productive of the destruction of the civil liberty of such citizens who could be effectually coerced by it.” Notwithstanding the “body of respectable men” who had drafted the Constitution, Yates and Lansing expressed their “sincerest concern” and their “decided and unreserved dissent.”

In a journal article taking a “new look” at the decision by Yates and Lansing to depart the Convention, Professor Susan Westbury suggests that the letter “should, perhaps, be regarded as part of the Clinton campaign against ratification as much as an accurate explanation for Yates and Lansing’s decision to abandon the Convention.”

Future blog posts will examine Yates and Lansing’s communications with Governor Clinton and other delegates. It will be argued that Yates and Lansing’s position in opposing the Constitution was fundamentally different than other dissenting delegates who merely wanted a bill of rights. This post was updated with Yates Returns Part IV, which contains additional archival research to date.