Robert C. Livingston and the Annapolis Convention

A recent discovery in the NY Archives provides an answer, but raises new questions

The Annapolis Convention was an important precursor to the Constitutional Convention. Despite its importance, historians have had only limited tools to study the Convention which took place over four days in September of 1786. This article summarizes a new discovery in the New York Archives that provides a definitive answer to one long standing question, but opens the door to more intriguing inquiries which will be discussed in Part II. Part II asks the question, what was the rush to depart Annapolis, when more delegates were still en route?

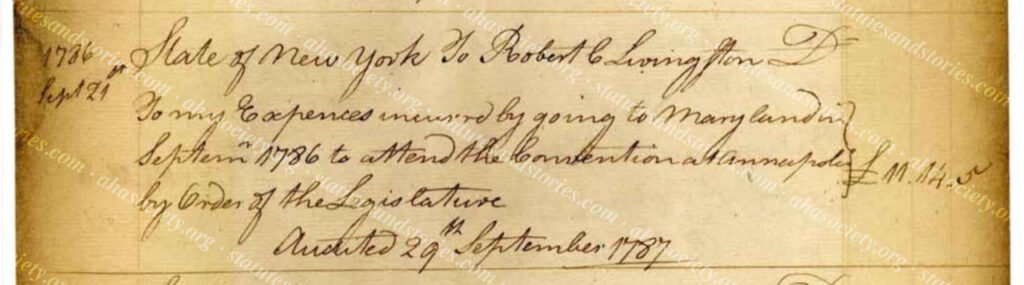

As pictured below, we now have proof that New York appointee Robert C. Livingston attempted in good faith to attend the Annapolis Convention. For many years, Livingston’s “attendance” had been subject to question, including whether he was paid for his time as a “commissioner” by the State of New York.

Alexander Hamilton and Egbert Benson travelled together to Annapolis. Due to prior business commitments, Livingston’s departure to Annapolis was delayed. Nevertheless, we now have verification that Livingston arrived in Maryland shortly after the Annapolis Convention adjourned. Thus, the recently revealed archival record dated 21 September 1786 affirmatively proves that all three New York commissioners did in fact travel to the Annapolis Convention. While this revelation may appear trivial, it is important to recognize that “three” New York “commissioners” were required by the 5 May 1786 Resolution of the New York Legislature appointing the New York delegation.

In other words, Robert C. Livingston was one of six commissioners appointed by New York to attend the Annapolis Convention. Yet, the 14 September Report of the Annapolis Convention was only signed by two New York commissioners: Alexander Hamilton and Egbert Benson. The Resolution of the NY Legislature appointing the six New York commissioners provided as follows:

Resolved that Robert R. Livingston, James Duane, Egbert Benson, Alexander Hamilton, Leonard Gansevoort and Robert C. Livingston Esquires, or any three of them, be Commissioners on the part of this State, to meet with such Commissioners, as are, or may be appointed by the other States in the Union; at such Time and place, as shall be agreed upon by the said Commissioners; to take into consideration the Trade and Commerce of the United States; to consider how far an uniform System in their Commercial Intercourse and Regulations, may be necessary to their common Interest and permanent Harmony; and to report to the several States, such an Act relative to this great Object, as when unanimously ratified by them, will enable the United States in Congress Assembled, to provide for the same; and that the said Commissioners or any three of them do make a report of their proceedings to the Legislature at their next Meeting. (emphasis added)

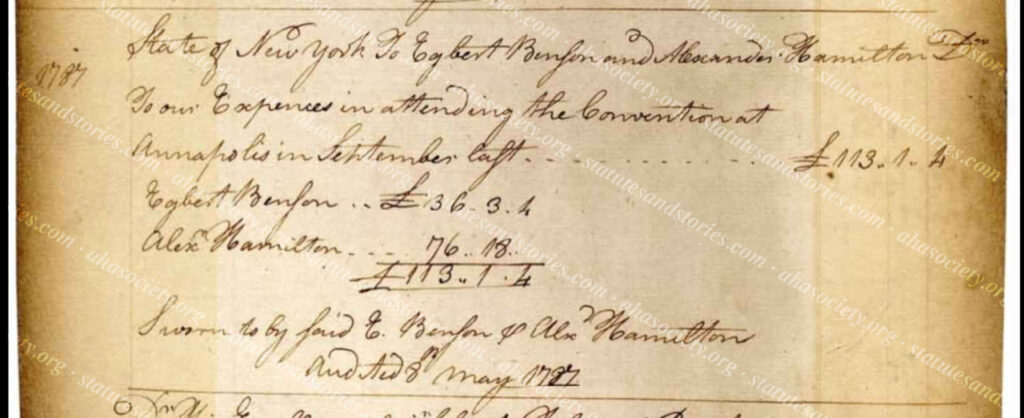

Pictured above is the newly revealed record found in the New York State Archives demonstrating Robert C. Livingston was paid 11 pounds, 14 shilling and 5 pence “for expenses incurred by going to Maryland in September 1786 to attend the Convention in Annapolis by order of the Legislature.” Pictured below is a second account entry evidencing that Hamilton and Benson were paid the substantially larger sum of 113 pounds, 1 shilling, and 4 pence. Based on what we know, this discrepancy in the reimbursement amounts between Hamilton/Benson and Livingston makes perfect sense. Yet, these records raise new questions.

Background about the Annapolis Convention

The Annapolis Convention met from September 11 to September 14, 1786. While the Annapolis Convention lacked the requisite quorum of seven states necessary to conduct business, the commissioners in attendance were undeterred. Led by Alexander Hamilton, the Annapolis Convention appropriately deserves credit for using the occasion to call for the convening of the Constitutional Convention the following year:

to meet at Philadelphia on the second Monday in May next to take into consideration the situation of the United States, to devise such further provisions as shall appear to them necessary to render the constitution of the Fœderal Government adequate to the exigencies of the Union; and to report such an Act for that purpose to the United States in Congress Assembled, as when agreed to, by them, and afterwards confirmed by the Legislatures of every State will effectually provide for the same.

Rather than accepting defeat, historian Joseph Ellis describes Hamilton’s “out-front leadership in its most flamboyant form” at the Annapolis Convention. “A convention called to address the modest matter of commercial reform had just failed to attract even a quorum, and now Hamilton was using the occasion to announce the date for another convention that would tackle all the problems affecting the confederation at once.” For Ellis this moment was “a display of almost preposterous audacity” by Hamilton.

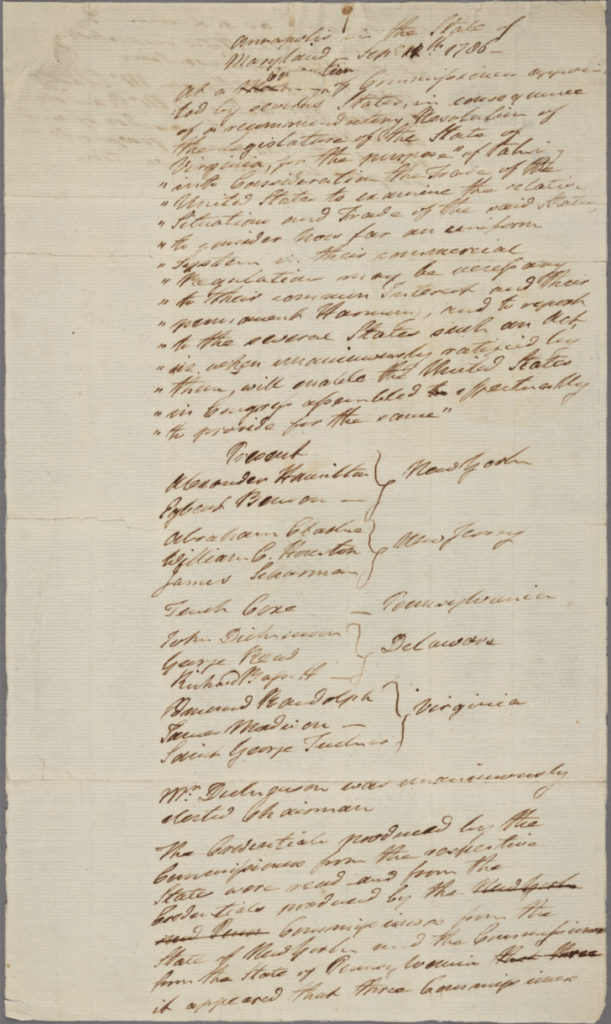

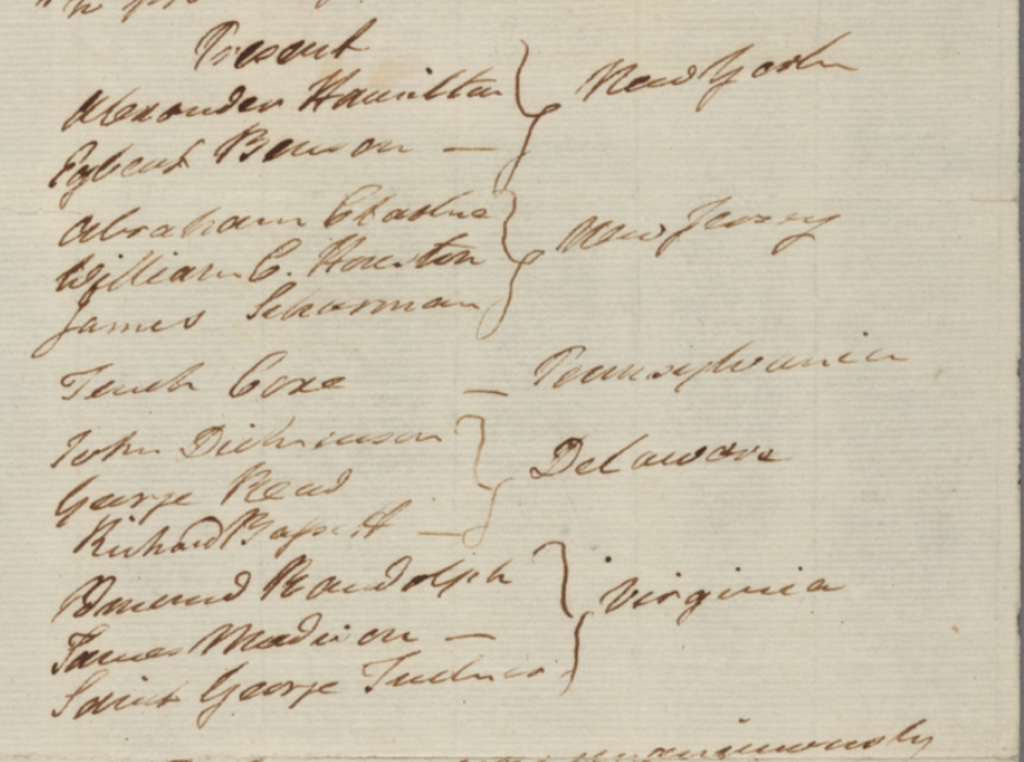

There can be no doubt that James Madison was one of the most dedicated and diligent founders. As was his practice, Madison took detailed notes at the Confederation Congress in the early 1780s and during the Constitutional Convention in 1787. Unfortunately, Madison didn’t record the discussions at the Annapolis Convention. Accordingly, the best primary source for the proceedings of the Annapolis Convention are the concise minutes taken by Hamilton’s colleague, Egbert Benson (New York’s Attorney General). Pictured below are the names of the attendees listed in Benson’s minutes:

As described by Benson’s minutes, it was “inexpedient for this Convention, in which so few States are represented, to proceed in the business committed to them…” Nevertheless, a committee was appointed to prepare an address/report to the several states. The minutes reflect that it was “Ordered that Mr. Benson, Mr. [Abraham] Clarke, Mr. [Tench] Coxe, Mr. [George] Read, and Mr. [Edmund] Randolph be a Committee to consider of and report the measures proper to be adopted by this Convention.”

Perhaps the most important resource for the proceedings of the Annapolis Convention is its 14 September Report (or Address), which was written by Alexander Hamilton. We know that Hamilton wrote the report because James Madison freely and repeatedly admitted as much. Indeed, Alexander Hamilton is the first name listed at the top of the Report. Observing that the names of commissioners are not listed in alphabetical order, professor Michael Meyerson opines that Hamilton “implicitly” proclaimed his primary role as the Report’s author.

In Madison’s “Preface to Debates in the [Constitutional] Convention,” he explained that that the report of the Annapolis Convention “was drafted by Col: H and finally agreed to unanimously.” Likewise, Madison acknowledged in a 12 October 1804 letter to Noah Webster that “Mr. Hamilton was certainly the member who drafted the address.”

Interestingly, Hamilton was not a member of the committee appointed to draft the report. Yet, Hamilton found a way to prepare the draft, which ultimately was unanimously approved. While it was “inexpedient” for the Annapolis Convention to formally proceed when “so few States” were in attendance, the commissioners seized the opportunity to boldly call for the Philadelphia Convention. The rest is history.

In 1816 New York Attorney General Benson discussed the Annapolis Convention in his Memoirs. First, Benson confirms that Livingston gave notice “of a probable detention by business, for some days, at least.'” As confirmed by Madison, Benson also recounts that the report of the Annapolis Convention was drafted by Hamilton, “although not formally one of the committee.”

New (and old) Questions

One commonly held view of the Annapolis Convention is that only five states were willing to send delegates to the convention which was destined to fail. After all, not even the home state of Maryland was willing to send representatives to Annapolis. According to this narrative, the fortuitous outbreak of Shays’s Rebellion was the motivating factor that roused the other states from their slumber. While the importance of Shays’s Rebellion should not be overlooked, it may surprise many to learn that more than five states appointed commissioners to attend the Annapolis Convention.

It is true that the Annapolis report was only signed by twelve commissioners from five states (New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware and Virginia). Yet, representatives from three more states (North Carolina, Massachusetts and Rhode Island) were travelling to attend the Annapolis Convention when it adjourned. Curiously, these additional commissioners were never able to participate in the deliberations.

What? Why would the Annapolis Convention conclude after only four days if representatives from North Carolina, Massachussets and Rhode Island were on the road to Annapolis? Moreover, Robert C. Livingston from New York was also en route. Indeed, a total of nine states had elected delegates to attend the Annapolis Convention. Why close up shop with only five states (and twelve commissioners) on the record?

So why the rush to wrap up and go home? As described by Professor Jack N. Rakove, 18th century assemblies rarely “managed to muster a quorum on time.” During the ratification debate following the Constitutional Convention, at least one notable Anti-Federalist (writing as the Federal Farmer) criticized the Annapolis Convention for the way it was “hastily” adjourned “before the delegates of Massachusetts, and of the other states arrived….” The French chargé d’affaires, Louis Otto, found this theory credible in a 16 October 1786 letter to French Foreign Minister Vergennes.

This post will be continued in Part II which will discuss the evidence that the Annapolis commissioners purposely ended their work on September 14, to avoid anticipated objections by colleagues who were yet to arrive. Given the limited historical record, reasonable minds may disagree whether the Annapolis commissioners purposely rushed to conclude their work. Nevertheless, in the book This Constitution: Our Enduring Legacy Professor Rakove described the work of the Annapolis Convention as the “gamble at Annapolis.” According to Rakove:

…the initiative taken by the Annapolis commissioners set an important precedent for the delegates at Philadelphia, who also ignored their nominal duty to revise the existing Articles of Confederation and instead chose to frame a radically new constitution. One risky gamble thus led to another, for far greater stakes.

Additional reading:

Address of the Annapolis Convention

Egbert Benson, Memoir read before The Historical Society of the State of New York (1816)

James Madison, Preface to Debates in the Convention of 1787

The Documentary History of the Ratification of the Constitution, Digital Edition, Volume 1: Constitutional Documents and Records, 1776-1787 (Kaminski, Gaspare, et al.)

William Peters, A More Perfect Union: The Making of the United States Constitution (1987)

Bruce Ackerman & Neal Katyal, Our Uncoventional Founding, 62 Univ. of Chicago Law Rev (1995)

Jack N. Rakove, James Madison and the Creation of the American Republic (2002)