New discoveries from the Annapolis Convention raise intriguing questions

Did the Annapolis Convention purposely adjourn before a quorum arrived?

It is commonly understood that the Annapolis Convention was a “failure.” According to the prevailing narrative, the Annapolis Convention was forced to adjourn because it was unable to secure a quorum of at least seven states. Yet, new evidence suggests that the conventional understanding of the Annapolis Convention is wrong.

Recent discoveries in the New York State Archives shed new light on the behind the scenes deliberations at the Annapolis Convention. The ostensible purpose of the Convention was to address commercial matters. With representatives from only five states in attendance, it was deemed “inexpedient for this Convention, in which so few States are represented, to proceed in the business committed to them.”

Although the Annapolis Convention adjourned without addressing commercial matters and trade regulations, it is universally acknowledged that the Convention ultimately succeeded with its call for a broader Constitutional Convention. Alexander Hamilton is widely credited with seizing the opportunity in Annapolis to draft the Convention’s ambitious call for broader reform.

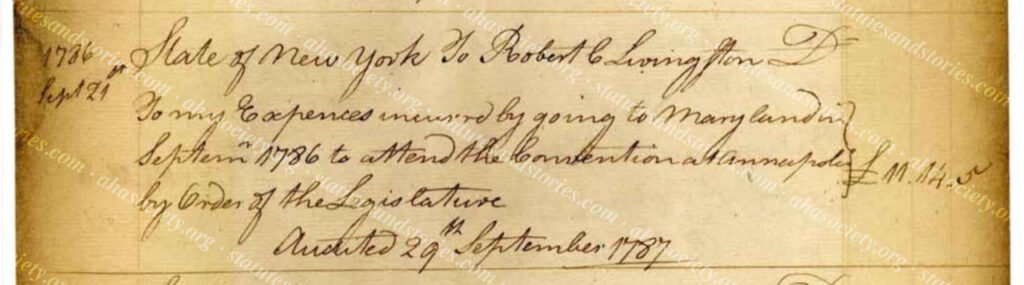

New evidence, however, suggests that the Annapolis Convention could have obtained a quorum if it had wanted to address the limited commercial matters within its purview. In particular, recently discovered financial records from Albany demonstrate that New York commissioner Robert C. Livingston travelled to Maryland in September to attend the Annapolis Convention. This discovery of Livingston’s travel to Annapolis is discussed in Part I. Prior to this revelation, it was assumed that Livingston never attempted to attend the Annapolis Convention.

Based on this new discovery, we now know that Livingston in fact arrived too late, after the Convention adjourned on 14 September 1787. Combined with contemporaneous newspaper reports and other primary sources, the historic record is now becoming clear. The Annapolis Convention could have obtained a quorum and engaged in substantive deliberations if it had wanted to do so. Instead, it appears likely that the Convention purposely adjourned on September 14, prior to the anticipated arrival of delegates from Massachusetts and Rhode Island.

Why would the Convention deliberately adjourn prior to the arrival of a quorum of delegates? This post, Part II, presents the thesis that Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and their allies in Annapolis realized that they could accomplish more by premature adjournment and “failure,” than they could by continuing with official deliberations in Annapolis. This thesis is hereinafter referred to as the Annapolis “END” (early narrated departure) thesis.

In other words, a unanimous call for further action was preferable to proceeding with their limited assigned task of commercial reform. This is particularly evident when examining the views of the delegates who were en route from Massachusetts.

Thus, the prevailing narrative that the futile Annapolis Convention was simply unable to secure a quorum needs to be re-examined. It is becoming increasingly clear that “failure” at the Annapolis Convention was purposely orchestrated on September 14 to be used as a Hamiltonian springboard. Historians already recognize that the Annapolis Convention’s call for further action in Philadelphia was bold and audacious. Arguably, even more so was the decision to prematurely adjourn prior to the arrival of the Massachusetts delegation, who likely would not have supported Hamilton and Madison’s ambitious vision of systematic, constitutional reform.

Survey of the evidence for the Annapolis END Thesis

The newly uncovered information discussed below, combined with a re-examination of existing primary sources, provides compelling evidence that the twelve delegates who signed the Annapolis Convention report were not interested in small scale commercial matters. Rather, led by Alexander Hamilton and James Madison, the Annapolis commissioners appear to have purposely adjourned on September 14, anticipating the arrival of a quorum within days.

Part I explains that the pending arrival of commissioner Robert C. Livingston would have completed New York’s three-member delegation, as required by the New York legislature. This blog – Part II – continues the discussion with evidence that the Annapolis Convention intentionally adjourned, prior to the arrival of the Massachusetts, Rhode Island and North Carolina delegations. Indeed, new evidence suggests that the Annapolis Convention could have secured a formal quorum within days, but surprisingly elected to precipitously adjourn on September 14.

With five states in attendance, the Annapolis Convention would only have needed two more state delegations to make an official quorum of seven states. Nevertheless, the Convention promptly adjourned after only four days. Curiously, the twelve commissioners who decided to adjourn appear to have known that the late arriving delegates from Massachusetts, Rhode Island and North Carolina were en route.

The contemporaneous newspaper reports, along with additional primary sources, establish that the following commissioners were traveling to Annapolis:

- Massachusetts commissioners Francis Dana, Samuel Breck and Lieutenant Governor Cushing (to be followed by Elbridge Gerry and Stephen Higginson);

- North Carolina commissioners Hugh Williamson and John Gray Blount;

- Rhode Island commissioner Jabez Bowen and Samuel Ward;

- Pennsylvania commissioners John Armstrong and George Clymer (who would have created a quorum for the Pennsylvania delegation by joining Tench Coxe, who had already arrived); and

- New York commissioner Robert C. Livingston (who would have created a quorum for the New York delegation by joining Alexander Hamilton and Egbert Benson who had already arrived).

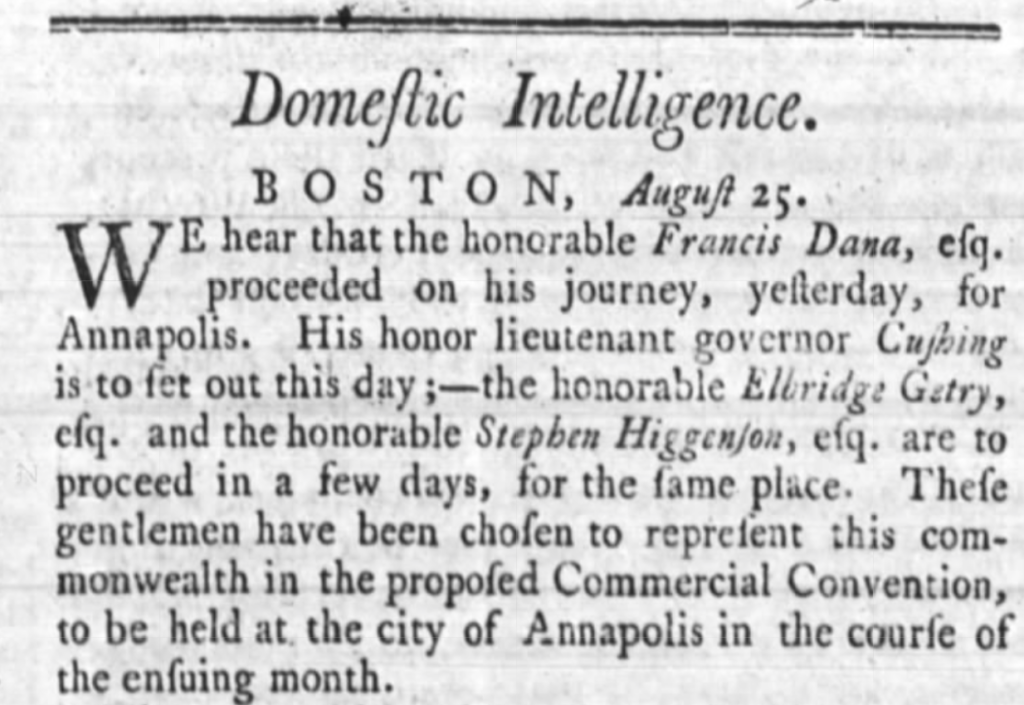

Perhaps most intriguing is the evidence that the Annapolis Commissioners likely would have known that a quorum was within reach. Pictured below is the widely reported news that unpredictable Massachusetts commissioners Elbridge Gerry and Stephen Higginson would be departing in late August to join fellow Massaschusetts commissioners Francis Dana and Lt. Governor Cushing, who departed Boston on August 25.

Once the news of Gerry and Higginson’s pending departure was reported on or about August 25, the news was quickly echoed by other newspapers that would easily have been seen by the Annapolis commissioners by September 14. Almost identical versions of the above report appeared in The Massachusetts Spy on August 31, The Connecticut Gazette on September 1; The New York Daily Advertiser on September 2; The Middlesex Gazette on September 4, The Pennsylvania Packet on September 5; The Pennsylvania Gazette and The Pennsylvania Journal on September 6; and The New York Journal and The New Haven Gazette on September 7. It is hard to believe that this news had not traveled to Annapolis by the decision to adjourn on September 14.

Even if these September newspaper reports that Gerry and Higginson were departing from Massachusetts were inaccurate, the fact remains that the twelve delegates in Annapolis would have been on notice of the imminent arrival of the Massachusetts delegation. While it is true that Connecticut, Maryland, South Carolina and Georgia did not appoint any commissioners, a nine-state Annapolis Convention could have proceeded with commercial matters, had that been their primary goal. The Annapolis END thesis argues, however, that the twelve signatories to the Annapolis Convention report were not interested in small-scale commercial matters.

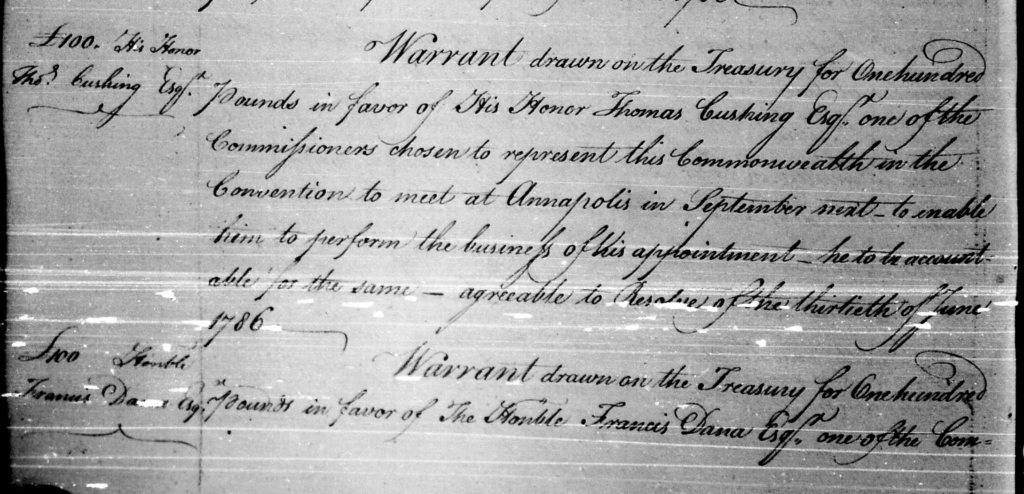

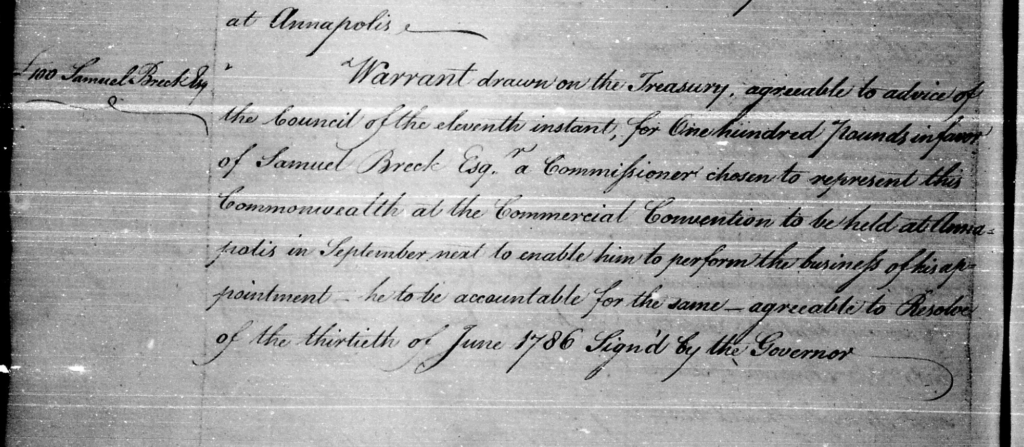

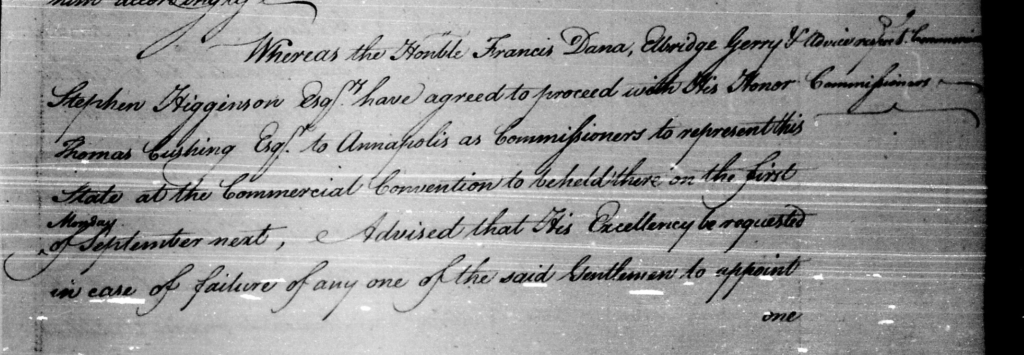

Copied below is proof that the Commonwealth of Massachusetts issued warrants in the sum of £100 each to Lt. Governor Cushing, Francis Dana, and Samuel Breck to cover the cost of their travel to Annapolis. To date, similar warrants have not been found for Gerry and Higginson, which suggests that they may not yet have left Boston, notwithstanding the newspaper reports of their imminent departure. Yet, the third image below suggests that Gerry and Higginson had “agreed” to attend the “Commercial Convention” to be held in Annapolis. All three images are excerpts from Executive Records of the Governor’s Council from August of 1786.

Massachusetts – letters from Cushing, Dana and Breck

Two letters from Massachusetts commissioners Cushing, Dana and Breck directly bear on this inquiry. On September 10th they wrote to Hamilton and Benson providing an update and request. The Massachusetts commissioners explained that they had just arrived in New York and would be setting off to Annapolis tomorrow. They requested that Hamilton and Benson advise the Annapolis Convention that they would be arriving within a week. The Massachusetts commissioners further explained that the Rhode Island commissioners would be departing on the 7th and could be expected “soon after us.” According to their September 10th letter:

Understanding on our arrival in this City last Fryday evening, that you had gone on for the Convention at Annapolis the week past, we take the Liberty to acquaint you and beg you to communicate to the Convention if it should be opened before we arrive there, that we shall set off from this Place tomorrow to join them, as Commissioners from the State of Massachusetts, which we hope to do in the course of this week. The Commissioners from Rhode Island were to sail from thence for this city on the 7th Instant; so that they may be expected soon after us.

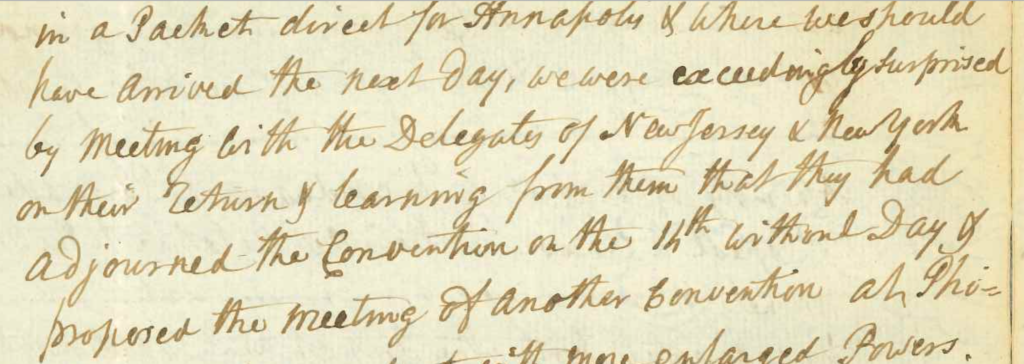

Less than a week later the Massachusetts delegation was “exceeding surprised” to learn that the Annapolis Convention had adjourned. In a letter dated September 16 to Massachusetts Governor Bowdoin, the Massachusetts commissioners provided a detailed account of their travels.

When they were only 30 miles away from the town of Rock Hall, Maryland, the Massachusetts commissioners encountered the New York and New Jersey delegations, who were returning home from Annapolis.

It is also telling that the September 16th letter observed that only three states “could be said with propriety to be represented when the dissolution of the whole convention took place.” While five states had representatives at the Annapolis Convention, the New York and Pennsylvania delegations had not yet obtained the minimum quorum to constitute a formal delegation.

Further supporting the Annapolis END Thesis is the statement in the September 16th letter that that the Annapolis Convention “had been informed by the public prints that we were on the way and might be daily expected and that North Carolina, Rhode Island and New Hampshire had appointed delegates.” The Annapolis END thesis suggests that the newspapers cited above are the “public prints” referenced in the September 16th letter.

As described by Professor Michael I. Meyerson:

The late-arriving commissioners fully expect that their fellow commissioners would wait for them. Thus, on Friday, September 15 the Massachusetts delegation was “exceedingly surprised” when, barely thirty miles from the town of Rock Hall, Maryland, where they were to take a boat to Annapolis, they came face to face with the New York and New Jersey delegates heading home.

According to Professor Meyerson, “[i]t seems strange, if not downright rude, for those attending the Annapolis convention to have ended it so abruptly, with full knowledge that other commissioners were on the way.” Meyerson notes that the “haste” to adjourn was “peculiar” and raised suspicions “about the motivation for the convention’s precipitous behavior.”

During the ratification debates the Anti-Federalist writer known as the “Federal Farmer” criticized the way that the Annapolis Convention “hastily” proposed the Constitutional Convention. According to the “Federal Farmer, No. 1”, in September of 1786:

a few men from the middle states met at Annapolis, and hastily proposed a convention to be held in May, 1787, for the purpose, generally, of amending the confederation-this was done before the delegates of Massachusetts, and of the other states arrived-still not a word was said about destroying the old constitution, and making a new one.

Connecting the dots, Professor Meyerson argues that “[t]he most likely reason for the unseemly haste appears to be that the Hamilton-led commissioners wanted to complete their call for a second, broader convention without the need to worry about possible objections that the latecomers – especially those from Massachusetts – might raise.” In support of this argument, Professor Meyerson cites to Professor Norman K. Risjord, who wrote that the Annapolis Convention “quickly adjourned lest new delegates arrive who wanted to enter some caveats on the record.” The recently located records cited above fully support Professor Meyerson and Risjord’s conjectures.

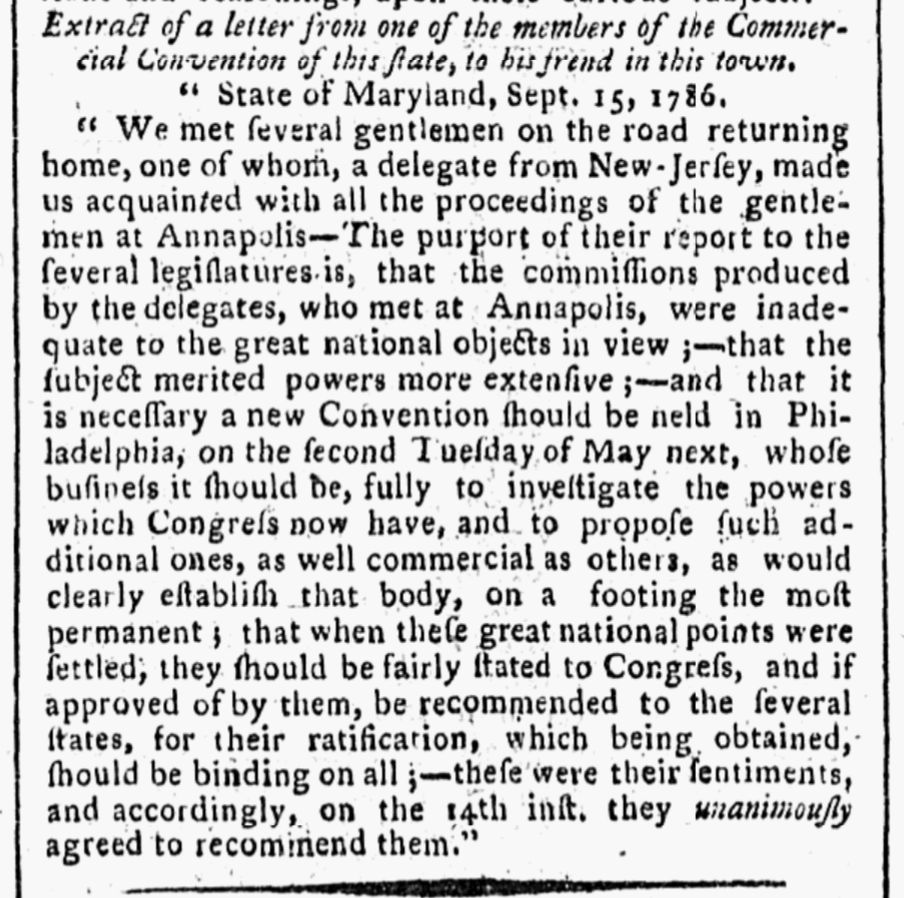

Pictured above is a newspaper report of a September 15th letter written by the returning Massachusetts commissioners on the road from Annapolis. An alternative explanation, which is not inconsistent with the Annapolis END Thesis, is contained in this September 15th letter. According to the Massachusetts commissioners, the purpose of the Annapolis report was that:

…the commissions produced by the delegates, who met at Annapolis, were inadequate to the great national objects in view; that the subject merited powers more extensive; and that it is necessary a new Convention should be held in Philadelphia, on the second Tuesday of May next, whose business it should be, fully to investigate the powers which Congress now have, and to propose such additional ones, as well commerical as others, as would clearly establish that body, on a footing the most permanent; that when these great national points were settled, they should be fairly stated to Congress, and if approved of by them, be recommended to the several states, for their ratification…

In other words, the September 15th letter admits that at least some of the Annapolis delegates did not think that they were empowered to address “the great national objects” that they hoped to solve in Philadelphia.

North Carolina – Williamson’s October 27th letter and “sufficient reasons for not sitting longer”

North Carolina commissioner Hugh Williamson also reported to his governor on his inability to timely arrive prior to adjournment of the Annapolis Convention. In a letter dated October 27 to North Carolina Governor Caswell, Williamson explained that fellow commissioner John Gray Blount was too ill to undertake the journey. “After some time Mr. Blount informed me that he was recovering and hoped to be able to undertake the journey in a few days, but he wished me in the meanwhile to proceed to Annapolis, with such papers and other information respecting the state of our commerce that I had been able to collect…”

On September 7th Williamson arrived in Norfolk, but was delayed by stormy weather. Regretting his late arrival, Williamson reported that “had they proceeded to business I should have been in time.” Interestingly, Williamson also commented that the Convention delegates had reasons for adjourning. According to Williamson, “[i]t was known that other states were on the road for Annapolis but the commissioners first assembled have given sufficient reasons for not sitting longer.”

While Williamson did not specify what the “sufficient reasons” were for adjourning on September 14, the Annapolis END thesis stipulates that the Annapolis Convention made the decision to “go big.” In other words, the Annapolis END thesis suggests that Hamilton and Madison convinced their colleagues that premature adjournment and a call for a second Convention was more important than small scale commerical reform.

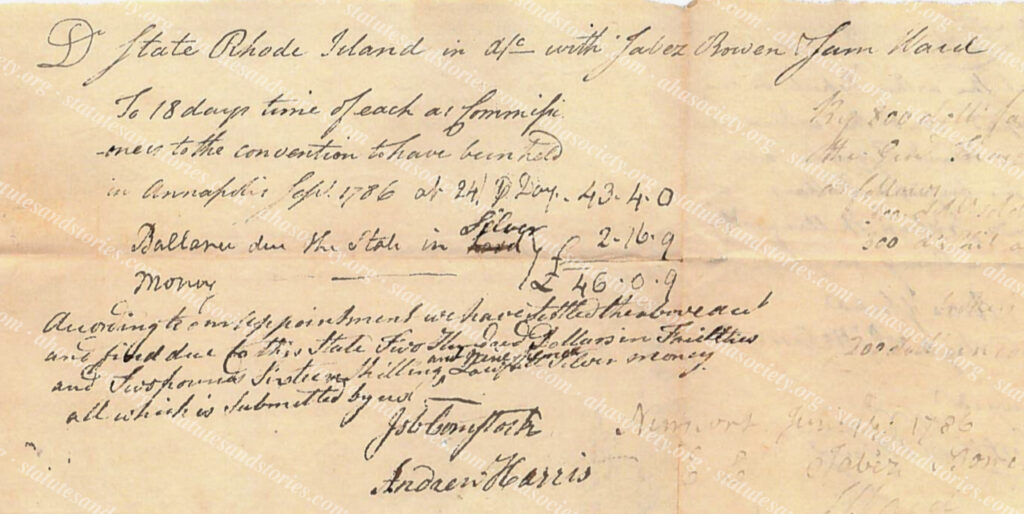

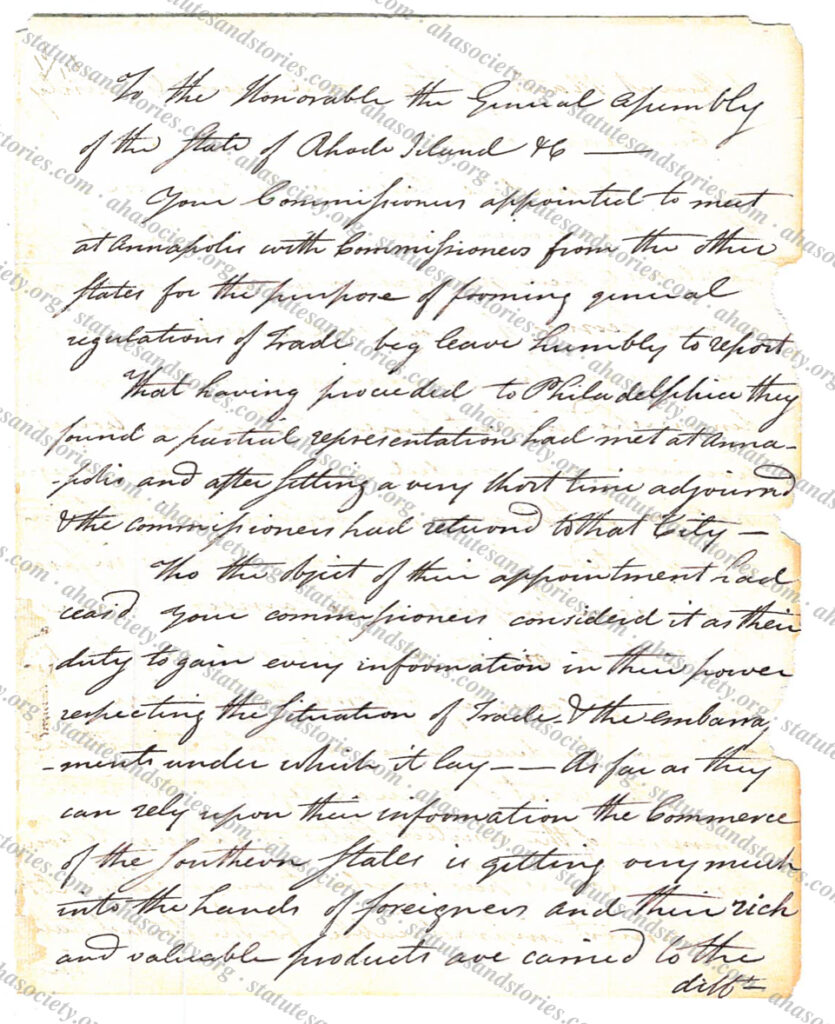

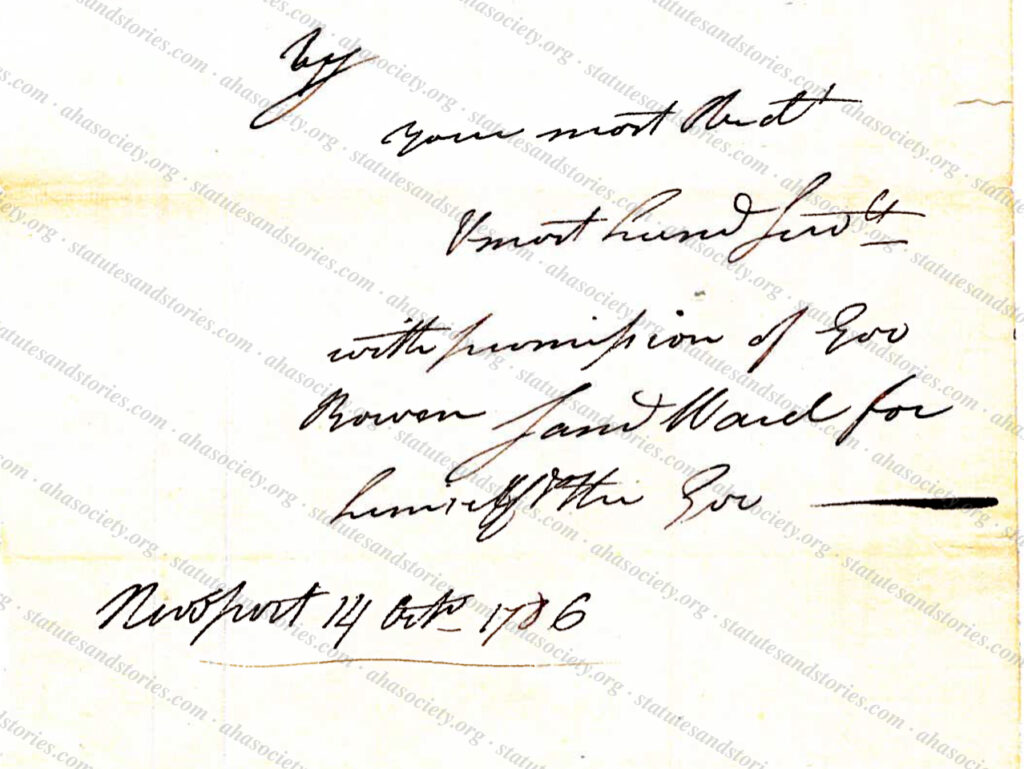

Rhode Island – proof of departure

As was the case with Massachusetts and North Carolina, Rhode Island’s commissioners were also traveling to Annapolis when they learned that the Annapolis Convention had adjourned. Records recently located in the Rhode Island State Archives provide uncontrovertable proof that Rhode Island Commissioners Jabez Bowen and Samuel Ward were paid for 18 days travel time for their aborted trip to Annapolis.

Also pictured below are excerpts from Bowen and Ward’s five page report to the General Assembly of Rhode Island. The report was written in Newport and is dated 14 October 1786. According to Bowen and Ward, “having proceeded to Philadelphia they found a partial representation had met at Annapolis and after sitting for a very short time adjourned…” Bowen and Ward describe that although “the object of their appointment had ceased” they “considered it as their duty to gain every information in their power respecting the situation of trade and the embarrasments under which it lay…”

It is noteworthy that Bowen and Ward observed that the Annapolis Convention adjourned after only a “very short time…” While beyond the scope of this blog post, it appears from their report that Bown and Ward would have been favorably inclined to a commerical agreement in Annapolis. This revelation is fully consistent with the Annapolis END thesis.

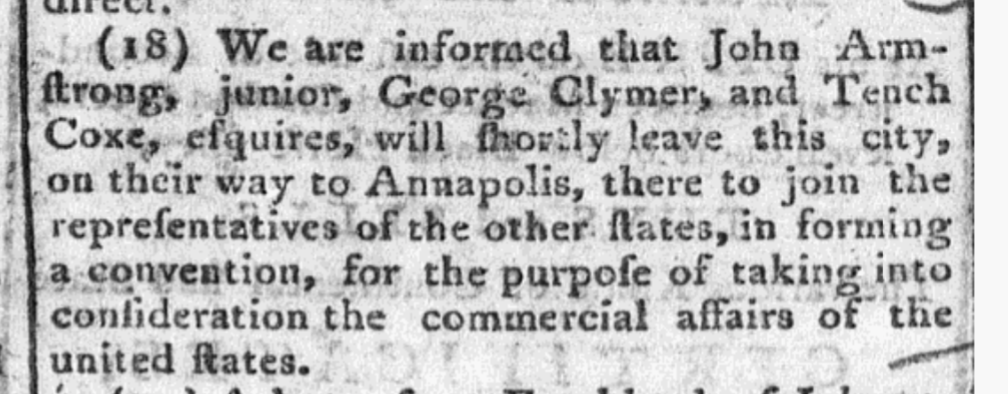

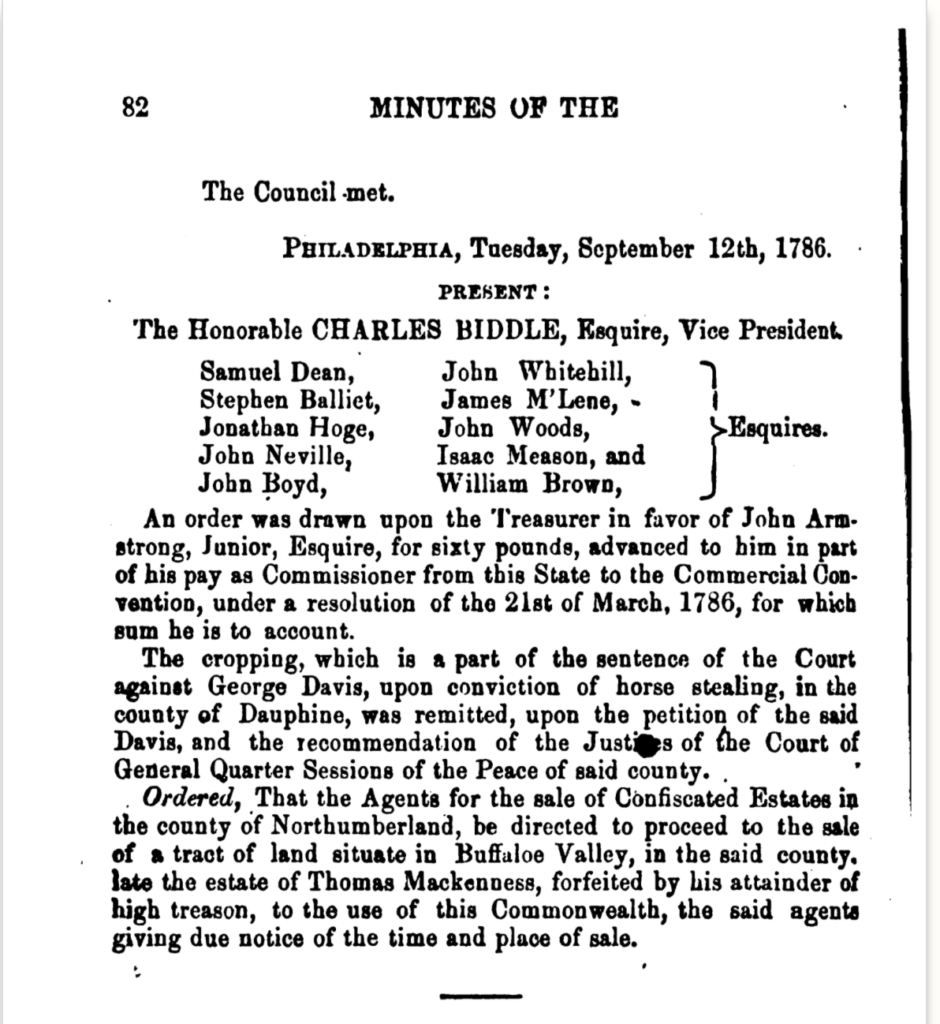

Pennsylvania – proof of departure of Armstrong and Clymer

Pennsylvania commissioner Tench Coxe attended the Annapolis Convention. As the sole Pennsyvania delegate on September 11, he could not comprise a functional delegation. Nevertheless, the following documents demonstrate that other Commisisoners from Pennsylvania were en route. The pending arrival of John Armstrong or George Clymer would have completed a quorum of Pennsylvania delegates, had the Convention not precipitously departed on September 14.

Pictured below is a sample newspaper report indicating that John Armstrong and George Clymer would be leaving Philadelphia “shortly” for Annapolis “for the purpose of taking into consideration the commerical affairs of the united states.” Among other newspapers, this information was reported by the Pennsylvania Journal on September 9th, the Pennsylvania Gazette on September 13th and the Pennsylviani Evening Herald.

According to the minutes of the Pennsylvania Supreme Executive Council on September 12 evidencing that, “an order was drawn upon the Treasurer in favor of John Armstrong” for £60 “advanced to him in part of his pay” as a Commissioner to attend the Annapolis Convention. At the time, 30 to 40 shillings per day was a common per diem for members of Congress. Accoringly, by advancing £60 pounds, Pennsylvania anticpated that Armstrong would be away for at least 30 days (60 pounds x 20 shillings per pound = 1,200 shillings ÷ 30 shillings per day = 40 days advance payment).

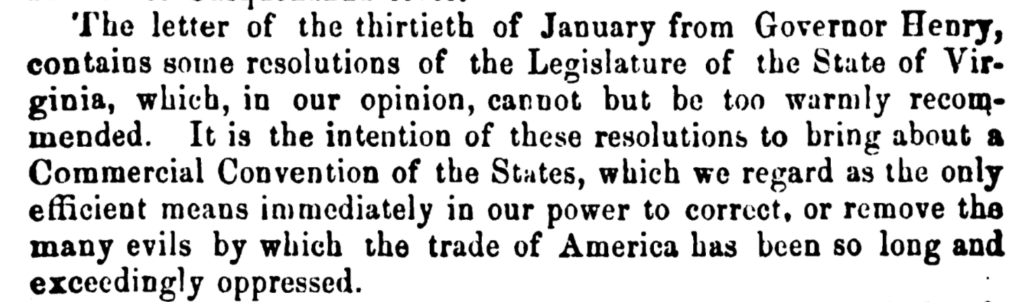

Interestingly, months earlier when Pennsylvania when considering appointing delegates to Annapolis, the Supreme Executive Council “warmly” recomended that Pennsylvania participate in the Annapolis Convention, “which we regard as the only efficient means immediately in our power to correct, or remove the many evils by which the trade of America has been so long and exceeedingly oppressed.” An excerpt from the February 22 message from the Supreme Exective Council to the Pennsylvania General Assembly is copied below. This is further evidence that Pennsylvania was interested in pursuing a commerical convention, but for the early departure on September 14.

New York – Benson’s memoirs

New York commissioner Egbert Benson was the New York Attorney General in 1786 when he attended the Annapolis Convention with Hamilton. Benson’s memoirs confirm that Hamilton drafted the Annapolis Convention report. According to Benson, “[t]he draft was by Mr. Hamilton, although not formally one of the committee.”

Benson’s memoirs also confirm that New York’s third delegate, Robert C. Livingston, was also planning on attending. The recently uncovered Livingston reimbursement in the New York Archives confirms that Livingston would have completed the three-member New York delegation. As described by Benson’s memoirs:

…the legislature of this State appointed their Commissioners, Messrs. Duane, Gansevoort, R. C. Livingston, Hamilton, and me. Mr. Gansevoort wholly declined the appointment; and when the time for the Convention to assemble approached, Mr. Duane gave notice to his colleagues of indisposition, and Mr. Livingston of a probable detention by business, for some days, at least.

Thus, Hamilton and Benson knew that Livingston was planning on attending the Annapolis Convention. While they wouldn’t have been able to predict the exact date of Livingston’s arrival, they knew that the formal requirements for a full three-member New York delegation would be satisfied when Livingston arrived. The Annapolis END Thesis suggests that Hamilton and Madison were not concerned with obtaining a legally sufficient quorum, since they had bigger fish to fry.

This post will continue in Part III (pending) which will discuss the likely reasons why the Annapolis delegates had concerns about the objectives of the Massachusetts delegation. As will be discussed in Part III, the Annapolis END Thesis asserts, ironically, that the Massachusetts delegates were strong supporters of limited commercial reform, but would have been hostile to the radical reform proposals recommended by Hamilton and Madison.

Additional Reading:

Norman K. Risjord, Chesapeake Politics, 1781-1800 at 266 (Columbia University Press, 1978)

Bruce Ackerman & Neal Katyal, Our Uncoventional Founding, 62 Univ. of Chicago Law Rev 475 (1995)

Stephen F. Knott & Tony Williams, Washington & Hamilton: The Alliance that Forged America (2015)