Hamilton at the Philadelphia Convention

During the Revolutionary War Alexander Hamilton was one of the first to publicly recognize the need for a stronger federal government. As early as 1780 in a letter to James Duane, Hamilton began calling for a convention to address the flaws in the Articles of Confederation. For Hamilton, the fundamental defect was a “want of power in Congress” which rendered the Articles unequal to the prosecution of the war or “the preservation of the union in peace.” His Continentalist essays argued that America had drawn the wrong lessons from the war. Fear of political power was resulting in anarchy.

In the preface to his notes on the Convention, James Madison credits Hamilton with suggesting to Congress on April 1, 1783 that a “general” convention be held with the object to “strengthen the Federal Constitution.” While serving in Congress in 1782-1783, Hamilton and Madison were unsuccessful in their attempt to provide a revenue source for Congress with the adoption of a 5% impost tax. While the impost was approved by Congress, it failed to obtain unanimous support by all states required by the Articles of Confederation.

At the Annapolis Convention in September of 1786, Hamilton played a critical role with James Madison calling for the Constitutional Convention to be held the following year. Hamilton drafted the Annapolis Convention Address requesting the appointment of commissioners “to devise such further provisions as shall appear to them necessary to render the constitution of the Fœderal Government adequate to the exigencies of the Union,” beginning on the second Monday in May, 1787.

After the Philadelphia Convention concluded, Hamilton worked hard to secure the ratification of the Constitution. In addition to the drafting of the Federalist Papers, Hamilton played a leading role at the New York ratification convention. Yet, many historians have been puzzled by Alexander Hamilton’s “uneven” performance at the Constitutional Convention. For a partial explanation here is a discussion of the behind the scenes story of the New York delegation, which was purposely configured by Governor Clinton as a three member delegation to limit Hamilton’s effectiveness in Philadelphia.

According to historian Marie Hecht, Hamilton’s role in the convention was “bizarre and undistinguished.” She readily admits, however, that “he became the sun, moon and stars in the cause of ratification.” For Hecht, “[t]here is no more striking example in history of passionate commitment to a cause that its defender distrusted than Hamilton’s to the United States Constitution.”

Historian Forrest McDonald notes Hamilton’s “seemingly inconsistent conduct” in Philadelphia and observes that Hamilton “contributed little to the deliberations at the convention and did not even bother to attend much of the time.” Of course, McDonald concedes that Hamilton “performed herculean labors to bring about its ratification.”

Historian Clinton Rossiter rates Hamilton’s performance during the summer of 1787 as an “inexplicable disappointment.” For Rossiter, “the wide gap between the possible and the actual in Hamilton’s performance in Philadelphia comes as an unpleasant shock…” Hamilton biographer Broadus Mitchell is more generous indicating that Hamilton “was to find his greater triumph in making not a constitution, but a country.”

This blog post summarizes Hamilton’s involvement with the Philadelphia Convention. After reviewing Hamilton’s activities during the summer of 1787, this post theorizes that Alexander Hamilton may have played a larger role at the Convention than is generally accepted. After each event on the timeline, the relevance for the Hamilton Authorship Thesis (HAT) is described.

The Hamilton Authorship Thesis (HAT) proposes that Hamilton drafted the Constitution’s 17 September 1787 transmittal letter (the Cover Letter). Click here for a more detailed discussion of Hamilton Authorship Thesis which identifies Hamilton’s “fingerprints” which suggest his authorship of the Cover Letter.

Hamilton’s Constitution Timeline

May 18, 1787 – Cincinnati meeting: Hamilton arrived in Philadelphia with Robert Yates. On May 18 he presented his credentials to the Society of the Cincinnati which was also meeting in Philadelphia. One can only wonder whether the May date for the Constitutional Convention was specifically selected by Hamilton and Madison to align with the previously scheduled Society of the Cincinnati meeting?

Possible significance for the Hamilton Authorship Thesis: Did Hamilton prepare the Cover Letter anticipating that the Society of the Cincinnati could assist with the public relations campaign that would be required to obtain ratification?

May 25, 1787 – June 29, 1787 – Initial Convention Attendance: On May 25, Hamilton attended the opening day of the Convention, which had been delayed since May 14 due to the lack of a quorum. Hamilton departed the Convention to return to New York leaving Philadelphia on or about June 30. Hamilton would later briefly attend on August 13. He returned to Philadelphia for his third and final visit to the Convention in early September. Hamilton re-appears in Madison’s daily notes beginning on September 6 through the end of the Convention on September 17. Click here for a link to Madison’s notes on May 25.

May 25 – Appointed to Rules Committee: On May 25, Hamilton was appointed to the Rules Committee, the Convention’s first Committee, which delivered its report on May 28. The three member Rules Committee was chaired by Virginia’s Judge George Wythe and also included Charles Pickney from South Carolina. Importantly, the Rules Committee established the strict secrecy rules which were intended to allow the delegates to speak freely. In an anonymous essay published under the pseudonym Amicus in 1792, Hamilton explained the importance of the Convention’s secrecy rules:

Had the deliberations been open while going on, the clamours of faction would have prevented any satisfactory result. Had they been afterwards disclosed, much food would have been afforded to inflammatory declamation. Propositions made without due reflection, and perhaps abandoned by the proposers themselves, on more mature reflection, would have been handles for a profusion of il-natured accusation.

Possible significance for the Hamilton Authorship Thesis: Did the Convention’s secrecy rules enable Hamilton to conceal his identity as the draftsman of the Cover Letter? The HAT Thesis theorizes that Hamilton had more to gain than any other delegate from the symbolic “Washington” signature on the Cover Letter.

June 18, 1787 – Hamilton’s all day speech: Hamilton gave a day long speech which was the only address of its kind at the Convention. Click here for a link to Hamilton’s June 18 speech and here for a link to Hamilton’s notes. Among other things Hamilton’s June 18 speech argued that both the New Jersey Plan and the Virginia Plan were inadequate. Hamilton offered his own plan, which may have made the Virginia Plan appear more moderate by comparison.

Possible significance for the Hamilton Authorship Thesis:

-

- Hamilton’s June 18 speech asks the question, “what provision shall we make for the happiness of our Country?” The word “happiness” appears three times in Madison’s notes of Hamilton’s speech. The Cover Letter concludes by stating that securing the “freedom and happiness” of the country so dear to us all is “our most ardent wish.”

- The June 18 speech lists five principles upon which a government should be based, including “interest,” “habitual attachment [habit],” and “influence.” These concepts are repeatedly mentioned in the Cover Letter.

- The June 18 speech responds to New York co-delegate John Lansing’s June 16 objections that the Convention lacked the power to propose the Virginia Plan, which Lansing thought was unlikely to be approved. During the Convention Lansing also argued that the loss of state sovereignty was only justified upon “evident necessity,” which Lansing didn’t think existed. The HAT Thesis suggests that the Cover Letter responds to Lansing by discussing the “necessity of a different organization.” The HAT further suggests that the Cover Letter responds to Lansing’s “improbability” of adoption argument by asserting that we “hope and believe” that the Constitution would in fact be adopted.

- Gouverneur Morris is reported to have described Hamilton’s speech as “the most able and impressive he had ever heard.” This is not surprising as many historians have described the fact that Morris was one of Hamilton’s closest friends (who gave the oration at his funeral). William Samuel Johnson, later to be named the Chairman of the Committee of Style, described the “boldness and decision” of Hamilton’s speech which was “praised by every body” but “supported by none.” Click here for a link to Johnson’s description. In a letter dated July 11 to Henry Knox, less than a month after Hamilton’s speech, Rufus King described Hamilton as “our very able and sagacious Friend Hamilton.”

July 3, 1787 – Letter to Washington: Hamilton wrote to George Washington expressing the fear that a “golden opportunity” was slipping away. Hamilton explained that “of necessity” he needed to remain in New York for another ten or twelve days but would return to Philadelphia if doing so would not be a “mere waste of time.” Click here for a link to Hamilton’s letter to Washington.

Possible significance for the Hamilton Authorship Thesis:

-

- In his July 3 letter to Washington, Hamilton begins by describing how he has “taken particular pains to discover the public sentiment” after he departed the Convention. In other words, Hamilton was measuring public opinion which he referred to as “the public mind.” It is clear from his July 3 letter that Hamilton understood the importance of public opinion and “public support.” The HAT Thesis suggests that Hamilton was ideally suited to write the Cover Letter, which would initiate the most successful public relations campaign in American history.

- Near the end of the July 3 letter Hamilton shares his concern that “we shall let slip the golden opportunity of rescuing the American empire from disunion anarchy and misery.” Hamilton admits that he is “seriously and deeply distressed.” The Cover Letter, which would be written two months later, uses the substantially similar phrase “seriously and deeply impressed” (a Hamilton fingerprint).

July 10, 1787 – Washington’s letter to Hamilton: Washington replied to Hamilton by letter dated July 10. According to Washington, the men who “oppose a strong & energetic government” were “narrow minded politicians or are under the influence of local views.” Washington indicated that “I am sorry you went away. I wish you were back.” Click here for a link to Washington’s July 10 letter to Hamilton.

Possible significance for the Hamilton Authorship Thesis: Among other things, Washington’s July 10 letter demonstrates that Hamilton and Washington were sharing their views and may have been coordinating during the Convention. The HAT Thesis suggests that one of the reasons why Hamilton returned was to write the Cover Letter with Washington’s signature, in the event that the Convention succeeded in agreeing on a new Constitution.

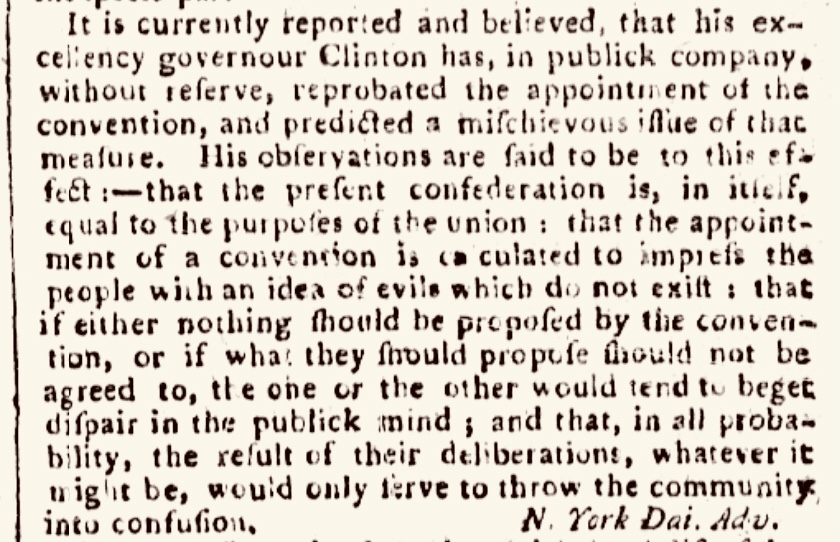

July 21, 1787 – Letter to NY Daily Advertiser: After having departed the Convention to attend to business in New York, Hamilton wrote a highly critical letter attacking New York Governor George Clinton for pre-judging the work of the Constitutional Convention, which was still meeting in Philadelphia. Click here for a link to Hamilton’s letter published in the NY Daily Advertiser.

Possible significance for the Hamilton Authorship Thesis:

-

- The fact that Hamilton was already taking the offensive against Governor Clinton suggests that he fully understood the uphill battle that the Constitution would face in New York. As described by Professor John Kaminski, Hamilton’s defense of the Constitution began two months before the Convention ended. “Seizing the initiative politically (as he had done during the war), Hamilton publicly denounced Governor Clinton as an opponent of the Convention”:

“Hamilton would not allow the governor to stay above the fray, waiting for an advantageous moment to take a public stand. Although harshly criticized in the press for alienating the governor, Hamilton rightly anticipated Clinton’s antifederalism and thus probably limited the governor’s effectiveness in opposing the new Constitution.”

- The July 21 letter begins with the statement that “[i]t is currently reported and believed” that Governor Clinton has publicly “reprobated the appointment of the Convention.” The Cover Letter contains the similar phrase that it is “hoped and believed” that the Constitution would be adopted.

- The fact that Hamilton was already taking the offensive against Governor Clinton suggests that he fully understood the uphill battle that the Constitution would face in New York. As described by Professor John Kaminski, Hamilton’s defense of the Constitution began two months before the Convention ended. “Seizing the initiative politically (as he had done during the war), Hamilton publicly denounced Governor Clinton as an opponent of the Convention”:

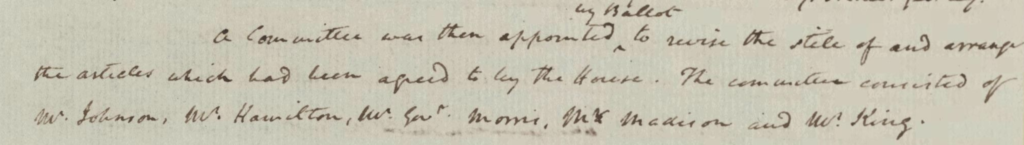

September 8, 1787 – Appointed to Committee on Style: On September 8 Hamilton is appointed to the Committee on Style and Arrangement, which was responsible for the final “polish” and arrangement of the Constitution. Many historians have commented that it was “surprising” that Hamilton was selected for this final committee since he had been absent from Philadelphia more than he was present. At least one historian has suggested that it was “shocking” that Hamilton was named to this committee given his attendance. Click here for a link to Madison’s notes on September 8.

Possible significance for the Hamilton Authorship Thesis:

-

- Based on the order of names listed in Madison’s notes, it is likely that Hamilton was the second delegate selected for the Committee on Style, after Chairman William Samuel Johnson. It is also plausible that Hamilton had more votes than any other committee member, other than Chairman Johnson. It becomes less surprising that the “celebrated truant” would be selected for this committee if there was a specific reason to appoint him. Historian Clinton Rossiter opines that the other four members of the Committee had earned their seats, in contrast to Hamilton who “had been back on the floor only three working days” when he was selected for the Committee. The HAT Thesis stipulates that one of the reasons why Hamilton may have been specifically selected for the Committee was so that he could draft the Cover Letter for George Washington.

- Despite their surprise that Hamilton was selected to this final committee, many historians acknowledge that Hamilton would not have been named unless he was respected by the Convention. According to Rossiter, “it speaks well” of Hamilton’s reputation “that he was asked to join these four stalwarts” on the Committee.

- Based on other correspondence during the Convention, delegates trusted Hamilton’s legal skills. For example, in two letters from Elbridge Gerry to his wife dated August 9 and August 14, Gerry described the work that Hamilton was doing settling the residuary estate of Mary Walters. Hamilton also intervened in an affair of honor to obviate the need for a duel between Convention delegate William Pierce of Georgia and Hamilton’s client, John Auldjo. Pierce famously wrote that “Hamilton is deservedly celebrated for his talents…there is no skimming over the surface of a subject with him, he must sink to the bottom to see what foundation it rests on.” Click here for a link to Pierce’s “character sketches.”

September 8, 1787 – Hamilton’s letter to to Duche: In a letter intended to be shared with the Marquis de Lafayette dated September 8, Hamilton predicted that “there is every reason to believe that if the new Constitution is adopted his friend General Washington will be the Chief.” Click here for a link to Hamilton’s letter to Mr. Duche which is held in the archives of the French Foreign Ministry, Consular Correspondence.

Possible significance for the Hamilton Authorship Thesis: Was it a coincidence that the same day that Hamilton is appointed to the Committee on Style he makes this prediction in a letter that potentially violates the rules of secrecy of the Convention? The HAT Thesis suggests that after being selected for the Committee on Style Hamilton knows that he will be able to draft the Cover Letter for Washington’s signature. If the HAT is correct, perhaps Hamilton already prepared a draft letter which he discussed with his co-Committee members on September 8.

September 12, 1787 – Committee on Style delivers its report: On September 12 the Committee on Style produced three documents: 1) the final draft of the Constitution; 2) the Cover Letter; and 3) the resolutions which set forth the recommended procedure for ratification. The Cover Letter was “read once throughout; and afterwards agreed to by paragraphs.” Click here for a link to Madison’s notes on September 12.

September 17, 1787 – Hamilton urges all delegates to sign: On the final day of the Convention, Hamilton observed that nobody’s ideas were “more remote” from the Constitution “than his own were known to be…” Nevertheless, Hamilton noted that, “[a] few characters of consequence, by opposing or even refusing to sign the Constitution, might do infinite mischief by kindling latent sparks which luck under an enthusiasm in favor of the convention which may soon subside.” In attempting to convince all delegates to sign, Hamilton explained that “it is possible to deliberate between anarchy and convulsion on one side, and the chance of good to be expected from the plan on the other.” Click here for a link to Madison’s notes for September 17.

Other dates that are relevant to the Hamilton Authorship Thesis

May 25, 1787 – Hamilton nominates Jackson as Convention Secretary: On the first day of the Convention, Hamilton nominated Major William Jackson for the job of Secretary. Jackson would be selected over Benjamin Franklin’s grandson, William Temple Franklin. Jackson was a member of the Society of the Cincinnati and had served on Washington’s staff during the war. His duties as Convention Secretary included maintaining secrecy of Convention proceedings, preparing the Convention Journal, destroying unwanted records at the conclusion of the Convention, and delivering the Constitution’s “plan” (which included the engrossed Constitution, Cover Letter and Resolutions) to Congress on September 20. Click here for a link to Madison’s notes on May 25.

September 8 or September 10 – Pinkney’s motion for an Address: According to Madison’s notes on September 10, Charles Pinkney moved that an Address be prepared to the People, to accompany the Constitution. James McHenry also kept notes at the Convention. McHenry’s notes seemingly conflict with Madison’s notes, suggesting that this motion was made two days earlier on September 8:

Click here for a link to Madison’s notes on September 10:

Mr. PINKNEY moved “that it be an instruction to the Committee for revising the stile and arrangement of the articles agreed on, to prepare an Address to the People, to accompany the present Constitution, and to be laid with the same before the U. States in Congress.”

Click here for a link to McHenry’s notes on September 8:

Agreed to the whole report with some amendments-and refered the printed paper etc to a committee of 5 to revise and place the several parts under their proper heads-with an instruction to bring in draught of a letter to Congress.

If McHenry is correct that a letter or “address” was discussed on September 8 (whether or not a motion was made on this date) this would strengthen the HAT Thesis that a reason for Hamilton’s appointment to the Committee was to prepare the letter. This possibility dovetails with Hamilton’s letter of September 8 predicting to Lafayette that Washington would be “chief.”

August 20 and August 28, 1787 – Hamilton’s letters to King: While in New York Hamilton wrote to Rufus King on August 20 requesting that he be notified when the conclusion of the Convention is at hand, “for I would chose to be present at that time.” A week later on August 27 Hamilton again requested to be notified “as I intended to be with you, for certain reasons, before the conclusion.” While Hamilton is cryptic in the August 28th letter, the HAT Thesis suggests that one of Hamilton’s reasons was to draft a Cover Letter for Washington’s signature, which would send the symbolic message that Washington supported the Constitution and would be willing to serve as President.

September 17, 1787 – King’s motion to maintain the secrecy of the Journals: According to Madison’s notes on September 17, the last day of the Convention Rufus King made a motion to maintain the secrecy of the Convention’s deliberations. The HAT Thesis suggests that this was not a coincidence that Hamilton’s friend and colleague on the Committee on Style made the following motion:

Mr. KING suggested that the Journals of the Convention should be either destroyed, or deposited in the custody of the President. He thought if suffered to be made public, a bad use would be made of them by those who would wish to prevent the adoption of the Constitution.

July 26, 1788 – New York ratifies the Constitution: New York became the 11th state to ratify the Constitution on July 26, 1788 by a slim 3 vote margin of 30 to 27. While the New York ratification convention began on June 17, both the Federalists and Anti-Federalists took their time painstakingly debating each provision. Prior to adjourning New York called for a second general convention to amend the Constitution, thus illustrating the underlying opposition to the Constitution in New York. Pictured above is a mural depicting Hamilton shaking hands with Governor Clinton following ratification in New York.